|

In 2009, I received the Japp Bakema Fellowship from the Netherlands Architecture Institute for my project ZERO. It was the height of the Great Recession and architects were laid off by the droves daily in Chicago. My architecture students who recently graduated were unable to find work or had to take up odd jobs to make ends meet. As an architect and a teacher, I came to realize the limitation of an architectural education that resides within an academy and cut off from the larger society, which architecture students will eventually be part of. I was dismayed by the narrow definition of architecture, the limited contributions of an architect besides a building, and the traditional client-architect relationship in practice. I saw the Great Recession as an opportunity to re-evaluate and re-frame architecture education and the role of an architect in society.

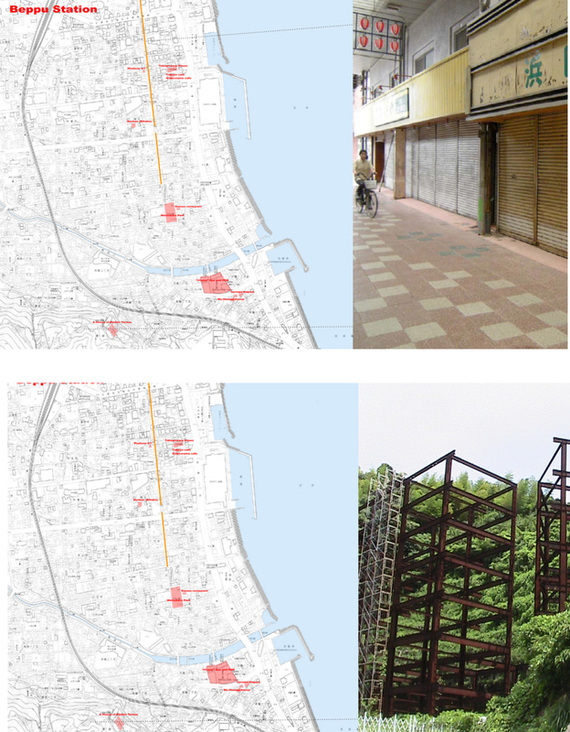

The fellowship afforded me the financial resources and time to research and document the various manifestations, causes, and meanings of emptiness, the values of unbuilding and how the local residents in Asian cities, many who were living along the margins of society, were able to occupy empty spaces for different durations and for social, commercial and personal uses. It opened my eyes to their ingenious, opportunistic, and informal use of empty spaces, found materials and urban infrastructures to fulfill their daily needs. Through ZERO, I discovered the relational dynamics of their occupations and actions, which were attributed to their creative use of scarce resources, and their ability to adapt, negotiate and utilize social relationships and existing spatial contexts to their advantage. Their occupation tactics were both a form of resistance and an adaptation to the planned spaces in the cities. I was fascinated by the spatial intelligence and material resourcefulness of the residents despite not receiving any formal design education. Its radical design amateurism and material relativism driven largely by pure purpose and need challenged what I learned in architecture school and the canons of good design. ZERO discovered the under and unrepresented everyday beauty and the potentiality of society’s detritus, be it material, social, cultural or spatial. The casual juxtaposition of the planned and spontaneous, the new and the discarded questioned our conventional notion of authenticity. The creative re-using of cast-off objects and materials by the residents was also a consoling knowledge in an age of throw-aways. ZERO was a timely springboard for my own search for an alternative design education and practice at a time of economic crisis, as well to broaden what an architect can contribute to society besides another building in a post-economic bubble age. My 5 min presentation for the event on Sep 16, 2017 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

The airport fascinates me as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Seldom do you find gathered in a building such a diversity of nationalities and cultures. In this slide, you see the Goddess of the Sea, Mazu and her 2 Heavenly assistants taking a business class flight from China to Malaysia for a religious event. They were issued boarding passes too. Future innovations will need to recognize and address the needs and experiences of a diverse group of travelers and users. In Singapore, the Changi Airport is a destination for the young and old who come to the airport for a variety of reasons. So much so that Changi may be the only airport that has so many signs discouraging students from studying. Changi is more than just an airport to the locals. It is a third place, a term coined by Ray Oldenburg to describe a place that people gather that is neither a home nor the office. First impressions count. The Copenhagen Airport is a showcase of Danish design. On the other hand, during the design of the Changi Airport in the 1970s, the Prime Minister then instructed the planners to plant rows of rain and palm trees along the highway leading from the airport to the city center, and that they be well maintained, for 2 reasons. First, it conveyed to arriving visitors that this is the tropics, and secondly, a signal to potential foreign investors that the city-state is well managed and the right place to invest their money in. This first impression was designed to reach a high point when the towers of capitalism, hidden by the trees, unfolded before your eyes as you reached the highest point of the Benjamin Sheares bridge after a 15 min taxi ride from the airport. Vice versa, the experience of the airport starts before arriving at the terminal. The in-town check-in service in Hong Kong is a good example. It gives back some control of time to the travelers who have to negotiate an environment that encourages consumption yet tightly controlled and surveilled. I believe designing the experience before and after the airport is as important as the airport itself. During the first day of the facilitation session in To Kwa Wan, I introduced the Circle of Gift Giving to the group. Sitting in a circle, each participant gave a small present to the person seating next to him or her. The ritual required the gift giver to share the source and meaning of the gift to the receiver. As the circle of gift giving enfolded, we shared funny, down to earth and poignant stories behind each gift. One participant forgot to bring a gift and she bought one in To Kwa Wan. Being practical minded, she bought a bottle of WD 40 from a car repair workshop as a gift and hoped it would be useful for the gift receiver. Another female participant gave a movie ticket to the participant next to her. She explained that it was from a movie date but her partner failed to turn up. She ended up leaving the movie theatre holding the unused ticket. A participant gave a small coin, which came from a memorable trip to Taiwan she made with her father, while another gave an old high school exercise book. She shared that the book brought back memories of her school days in Hong Kong after being away for many years.

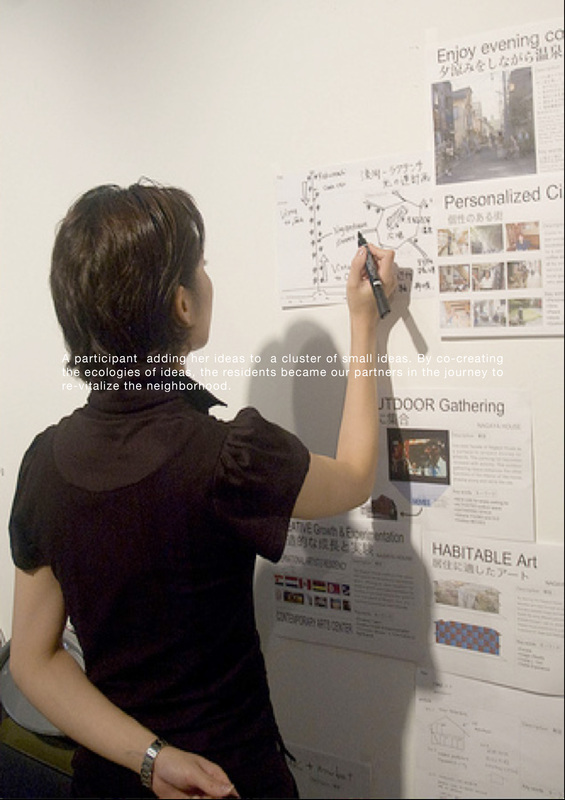

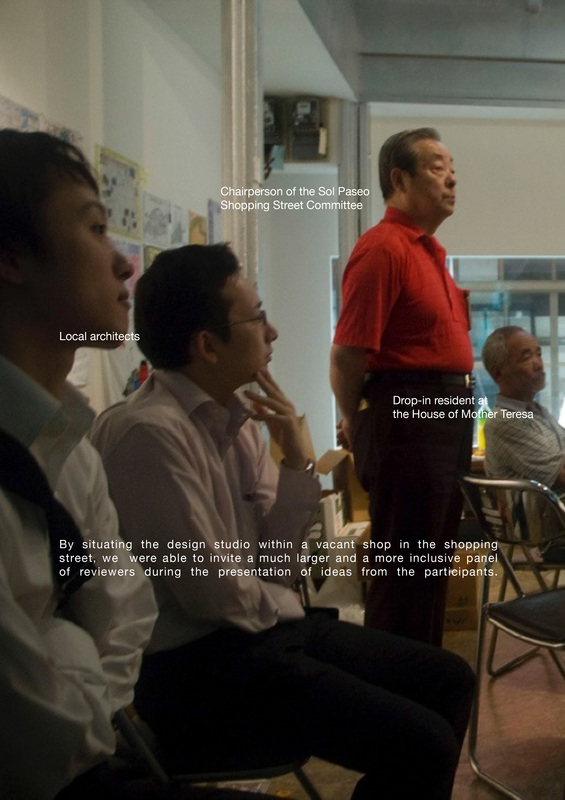

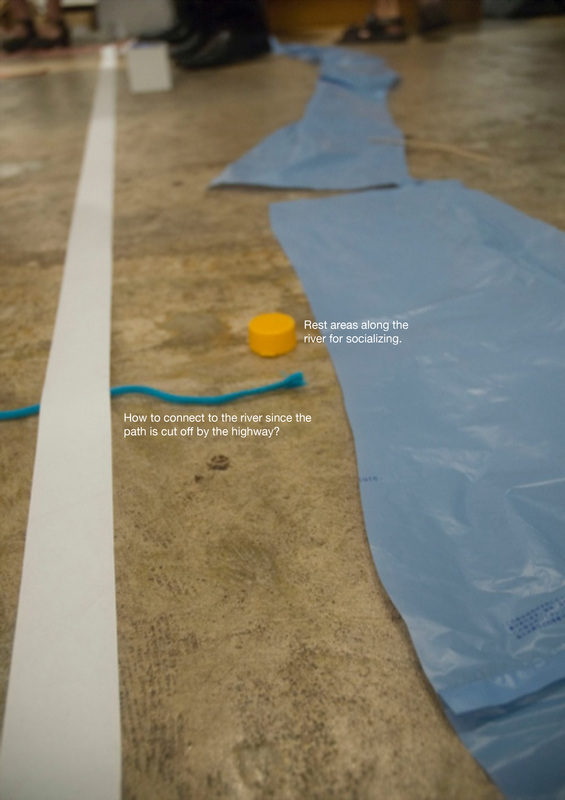

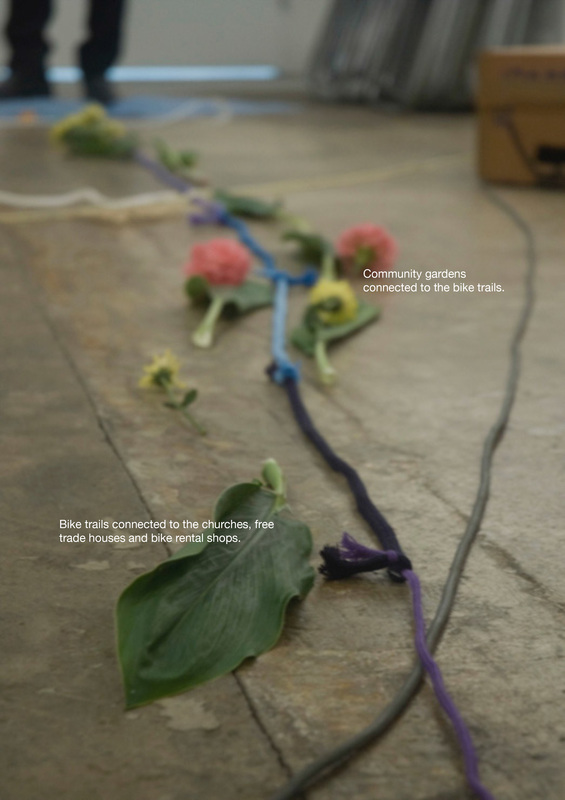

The participants had to learn from the sociocultural and economic life of To Kwa Wan residents, and come up with interesting ideas to archive the fast disappearing neighborhood over a one-month period. They came from all walks of life and were strangers to each other. Before diving deep into the task, I felt it was important to first form a community of learners through the ritual of gift giving. As Lewis Hyde in The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World so eloquently wrote, "...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears.” I was invited by the Make a Difference School in Hong Kong to be a guest facilitator for their 1- month in-situ studio in To Kwa Wan. Over 3 days in August, I gave a public lecture on the concept of Social Archiving and conducted discussions with the participants and local residents on the future of the neighborhood that was slated for re-development. Looking at To Kwa Wan superficially, one sees only the large number of car repair workshops, and would not have imagined a rich and diverse collection of social relations and history. Through my street conversations with the locals, I discovered a resident who played the flute to entertain passerby and gave a very good impression of singing birds. There was a pastry shop that have used the same 40-year old recipe since the day it opened for business, and even a car repair workshop that doubled up as a daycare for the child of a single parent who had to work part-time.

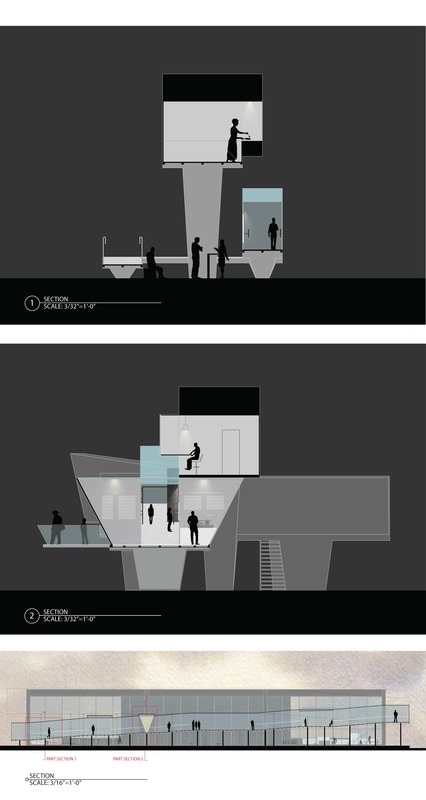

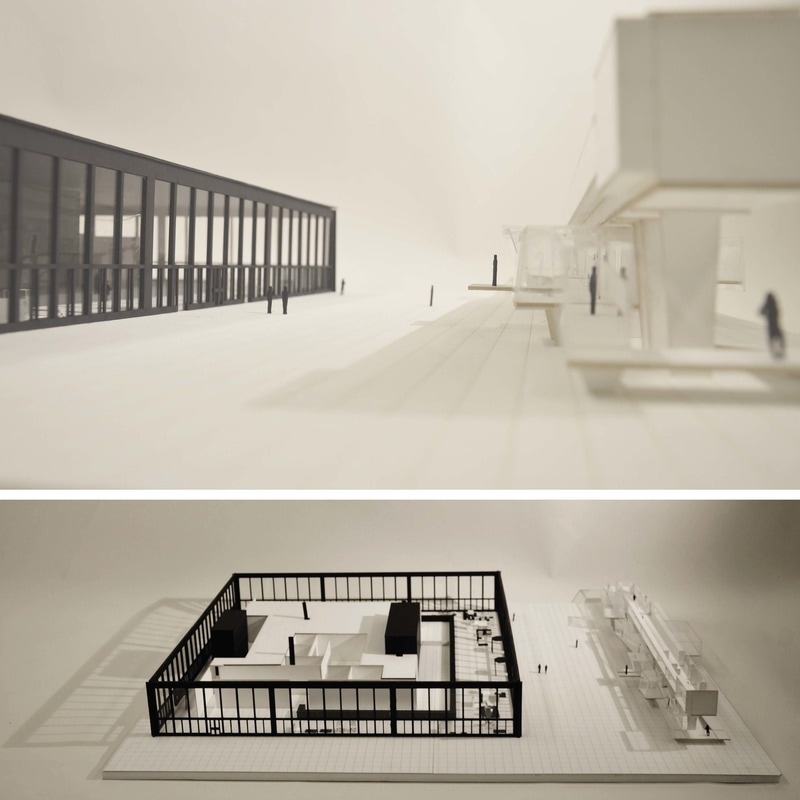

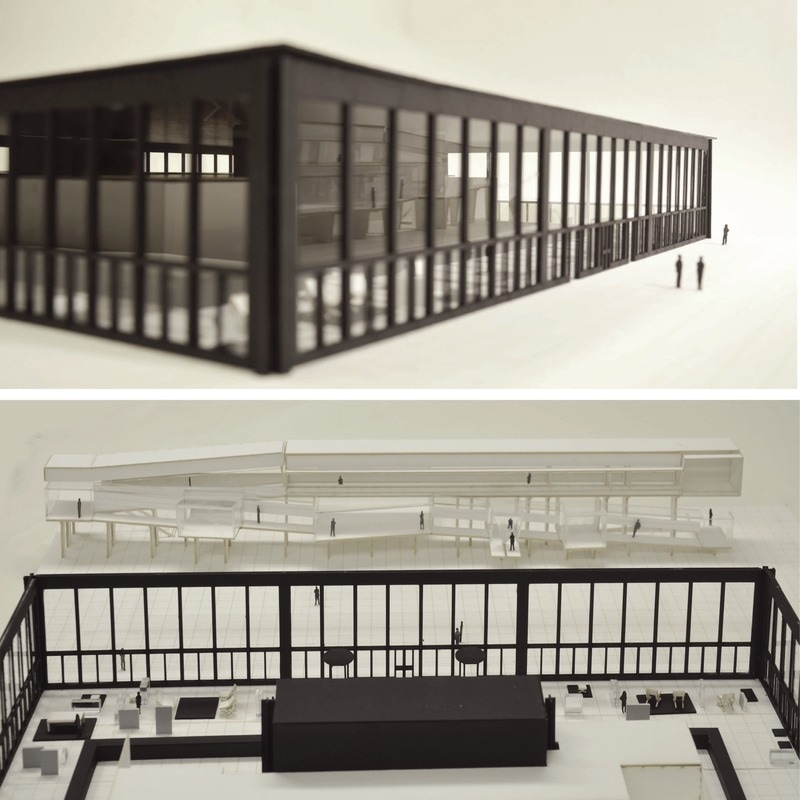

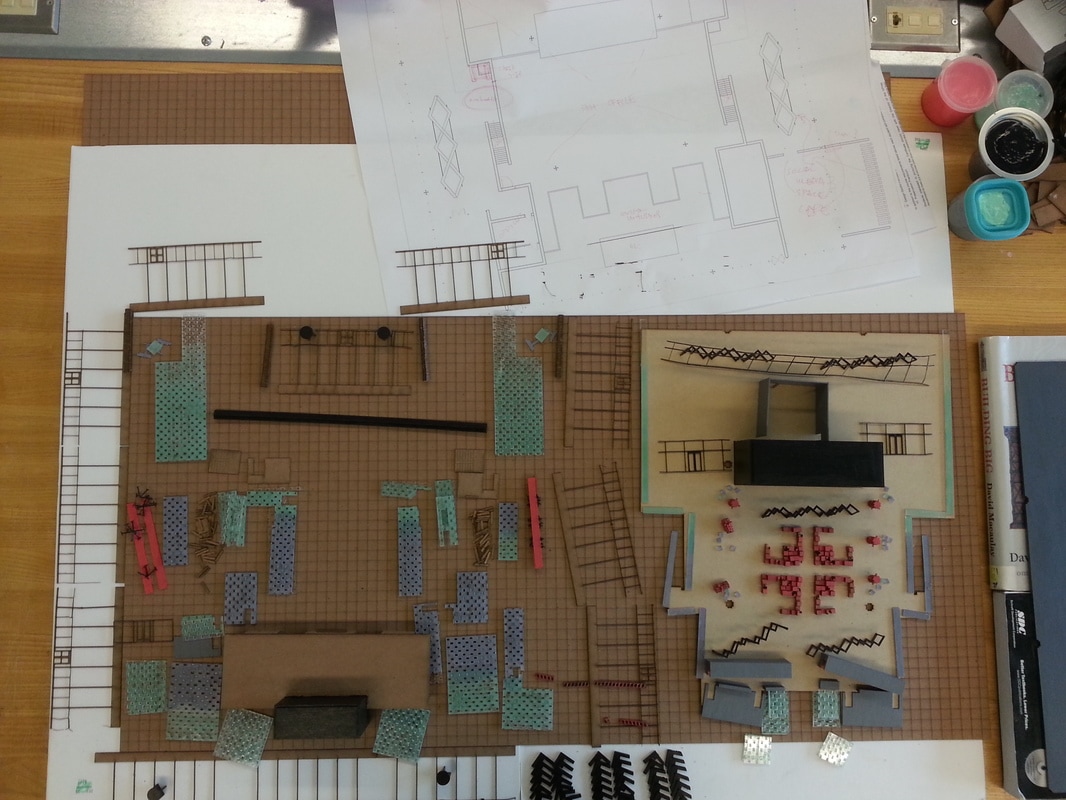

I was a mentor to a group of high school art students for over 5 days. Working collaboratively on a theme set by Singapore's Ministry of Education, the students developed spatial propositions via models and drawings. A showcase of the works was held on the last day.

The energy and enthusiasm was infectious. The works carried a spirit of shear audacity that defied my expectations. What to make of a web of bridges that dared to confront our discriminating mind? Who wouldn't want to be in a place of peace and tranquility amidst a sea of noise and distraction? Or be thrown into a reality gameshow that do not simplify our desire for and repulsion of digital connection? And not to forget a tower that fostered sociability over coffee, gardening and a good book. Countless ideas and possibilities to keep us curious, engaged and inspired! “Art and Design should not only be an object but an excuse for a dialogue.” Douglas Gordon and Thomas Kong

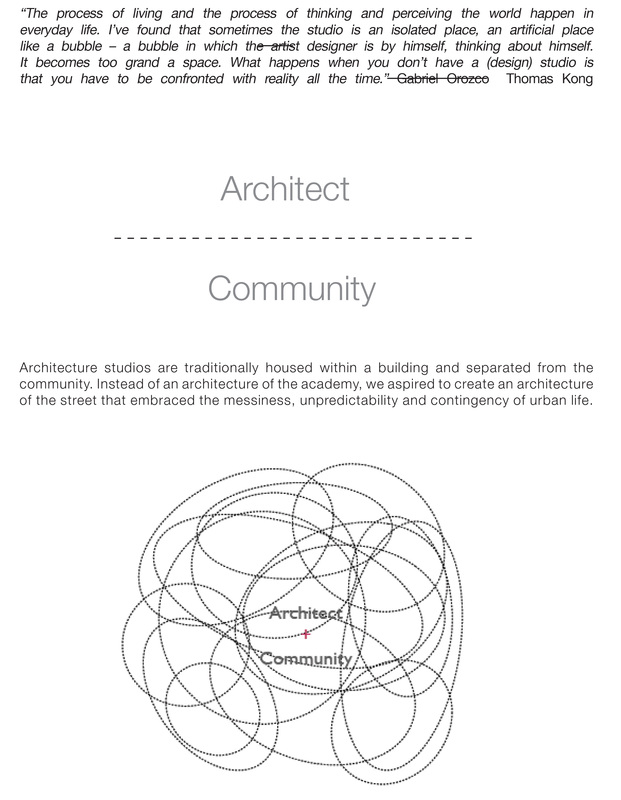

“When a person or a building disappears, everything becomes impregnated with that person's or building’s presence. Every single object as well as every space becomes a reminder of absence, as if absence were more important than presence.” Doris Salcedo and Thomas Kong “In art and design, everything is particular. The more particular and the more intimate you get, the more you can give in the piece.” Doris Salcedo and Thomas Kong “I'm often asked the same question: What in your work comes from your own culture? As if I have a recipe and I can actually isolate the Arab or Asian ingredient, the woman or man ingredient, the Palestinian or Singaporean ingredient. People often expect tidy definitions of otherness, as if identity is something fixed and easily definable.” Mona Hatoum and Thomas Kong “Every day, we came to [the exhibition space] to work together. We continued to organise these things and spaces. So actually, this exhibition is not about displaying, but about organizing spaces. Song Dong and Thomas Kong “The process of living and the process of thinking and perceiving the world happen in everyday life. I’ve found that sometimes the studio is an isolated place, an artificial place like a bubble – a bubble in which the artist and designer is by himself or herself, thinking about himself or herself. It becomes too grand a space. What happens when you don’t have a studio is that you have to be confronted with reality all the time.” Gabriel Orozco and Thomas Kong “I always want to design a frame or a building or structure that can be open to everybody.” Ai Weiwei and Thomas Kong “Designing and Architecture is not a profession, it is an attitude.” László Moholy-Nagy and Thomas Kong “An artist and a designer must constantly be faced with new and always different problems.” Cai Guo Qiang and Thomas Kong “Many artists and architects try to construct a world for themselves: from concept to format. From knowledge to inspiration, from a methodology to learn about, and to express the world.” Cai Guo Qiang and Thomas Kong “Caress the detail, the divine design detail.” Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong “Artists and designers themselves are not confined, but their output is.” Robert Smithson and Thomas Kong “Here is what we have to offer you in its most elaborate form in graduate advising -- confusion guided by a clear sense of purpose.” Gordon Matta Clark and Thomas Kong “A novelist and an architect are, like all mortals, more fully at home on the surface of the present than in the ooze of the past.” Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong Life or a building is a great sunrise. I do not see why death and unbuilding should not be an even greater one. Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong The pages and spaces are still blank, but there is a miraculous feeling of the words and lives being there, written in invisible ink and clamoring to become visible. Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong It ought to make us feel ashamed when we talk like we know what we’re talking about when we talk about love and design. Raymond Carver and Thomas Kong You’ve got to work with your mistakes and intuitions until they look intended. Understand? Raymond Carver and Thomas Kong If you only read the design books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong I dream and design. Sometimes I think that’s the only right thing to do. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong Death or unbuilding is not the opposite of life or building, but a part of it. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong Francois Laplantine’s book The Life of the Senses debunks the myth of Western rationality and category thinking. Instead, he argues for a life that is enmeshed in the flow of our senses, which defies neat compartmentalizing. What is the implication for spatial and object designers, and those who teach design? How can we breakdown the silos of learning, and take up the challenge and the opportunities that a life fully engaged in the senses bring? He wrote,

“ Category thinking eschews that which is formed in crossings, transitions, unstable and ephemeral movements of oscillation. It opts, in a drastic manner, for the fixity of time, movement and the multiple, and opposes, in so doing, the tension of the between and the in-between. Yet, these exist. Between presence and absence, there is melancholy and its Lusitanian inflection that bears the name saudade. Between darkness and light, there is chiaroscuro. Between the retracted and the rolled out, there is the movement of loosening. Between wakefulness and dreaming, there is dreaminess. Between the expected and the unforeseen, the suspected. Between trust and mistrust, the slight doubt. Between the certainty of that which is named and the designated (the definition) and refusal to speak is that which can be suggested (Mallarmé) or shown (Wittgenstein). Between life and death, there is the spectral: ghosts, or as thry say in Haiti, Zombies, revenants as well as survivors.” The late New York Times journalist David Carr used the term Present Future to describe the state of journalism in the 21st century, where the present proliferation of news feeds that cater to a multitude of readers at this moment does not necessarily lead to a definitive, clear idea of what journalism will become in the future. Nonetheless, the future is slowly being shaped by these current developments and one should not shy away from them or be overly nostalgic with the past. Perhaps one can say the same for the future of architectural education and the practice of architecture? It is often convenient and easy to project a future scenario that celebrates technology (usually) and how it will herald a radical shift in the conceptualization, design, making and habitation of architectural spaces. However, we are also living in the present while making these projections; going through the daily mundane but necessary rituals that sustain our everyday life. The body we carry with us still retains the memories of thousands of years of evolution despite their continuing tempering by new technologies. Cultural background too, influences our disposition towards new ideas and discoveries, which affects how fast the future becomes the present. By retaining the present with the future is a wise and prudent step in our desire to discover what lies beyond the horizon.

The word design is often used as a noun and a verb. The OED defines design as

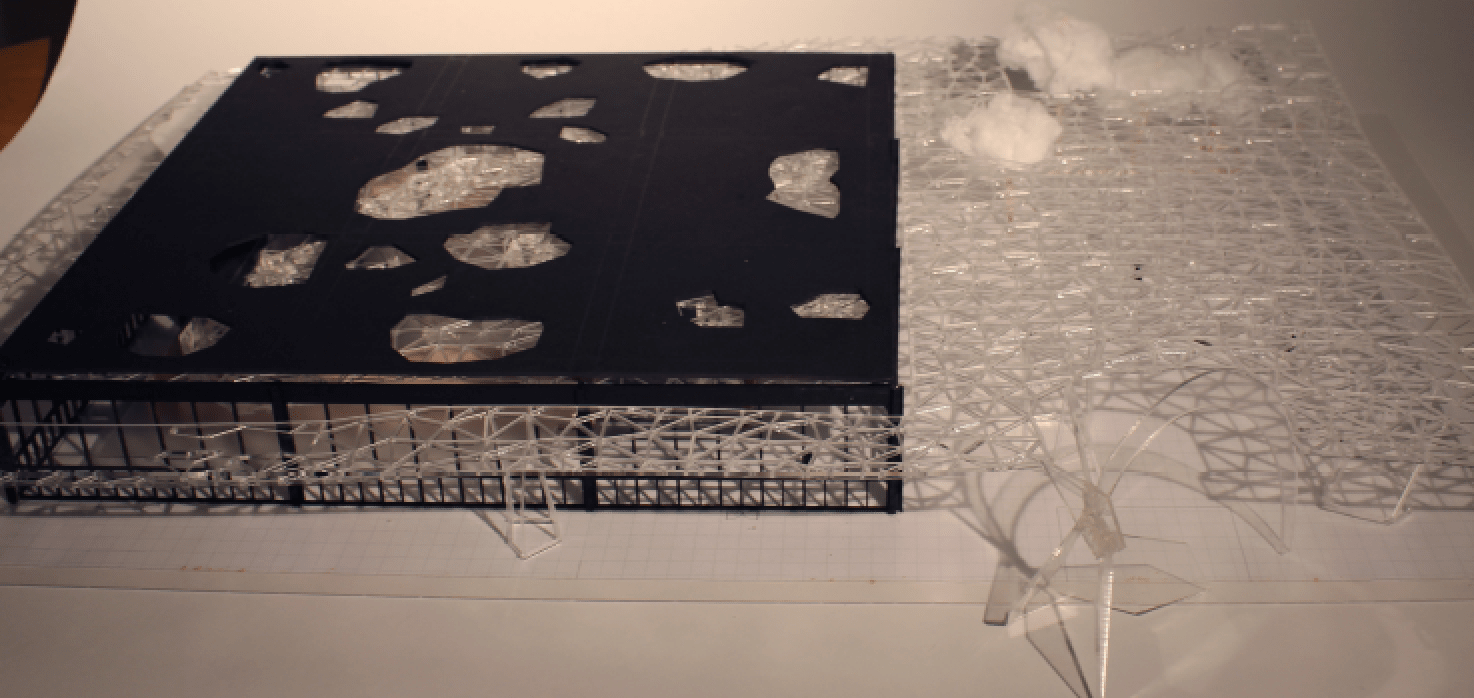

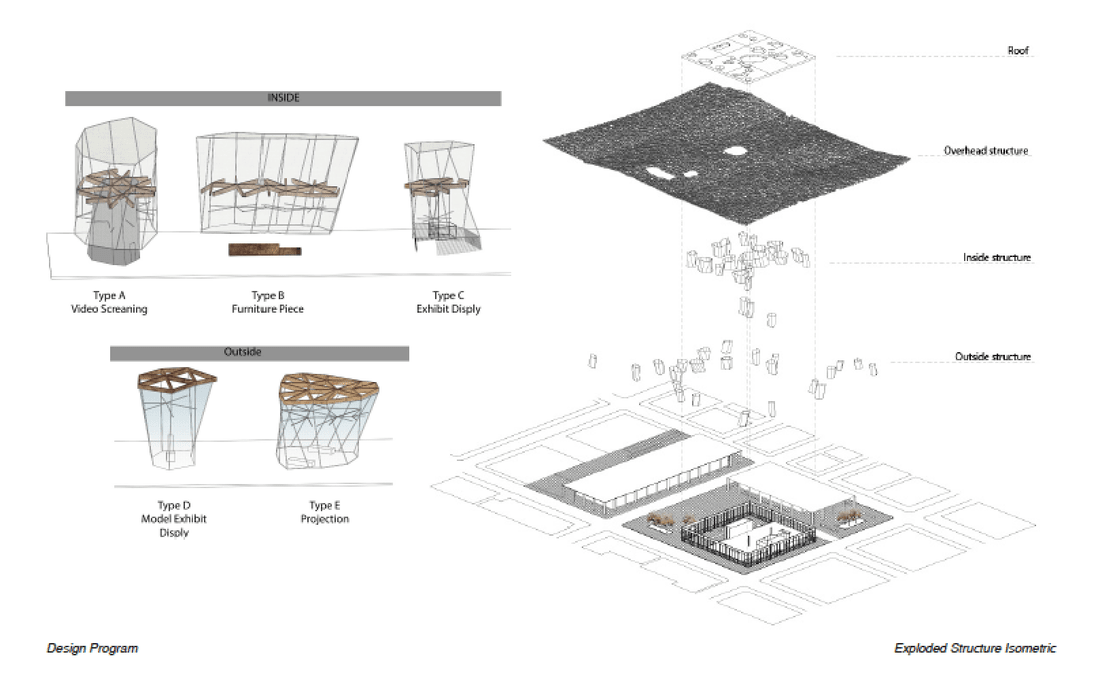

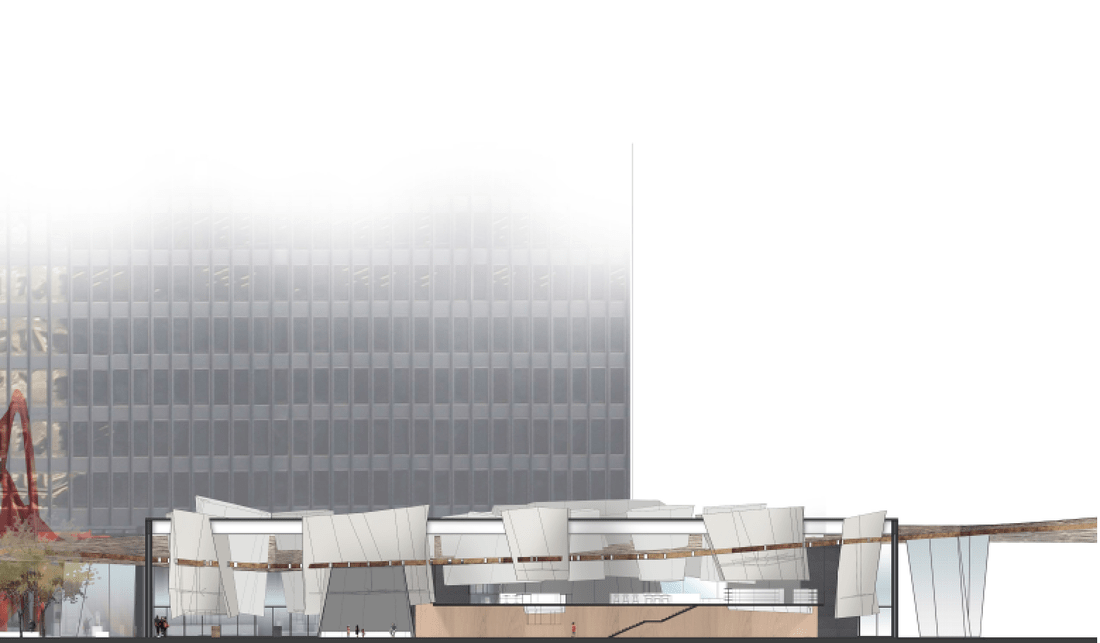

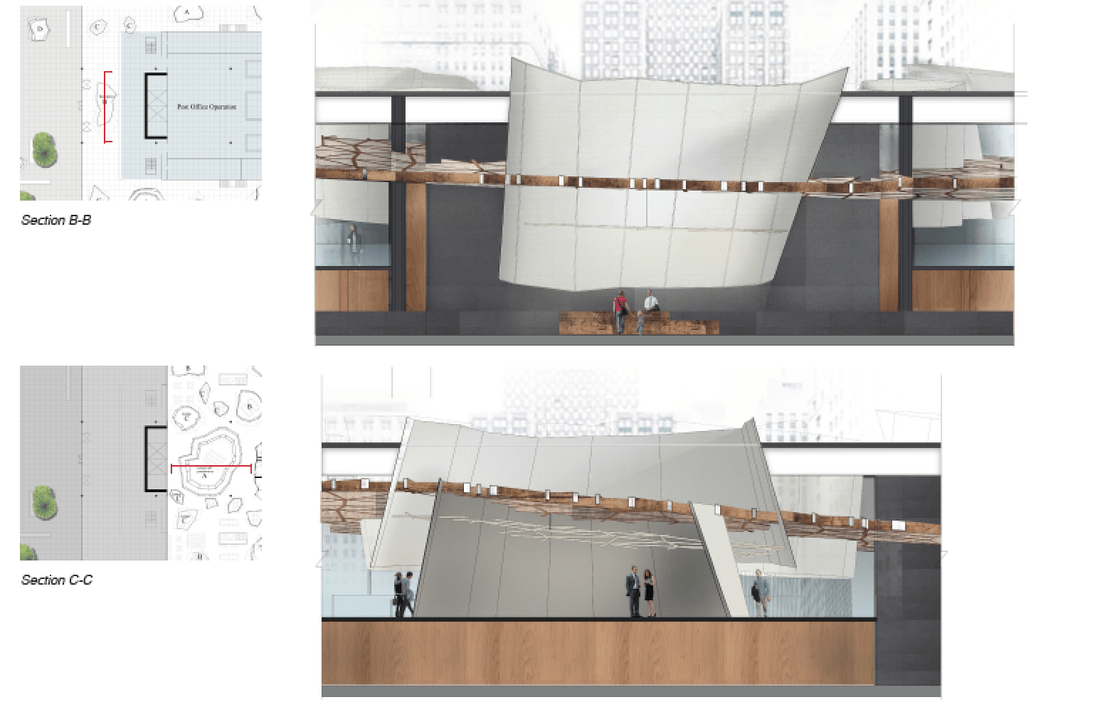

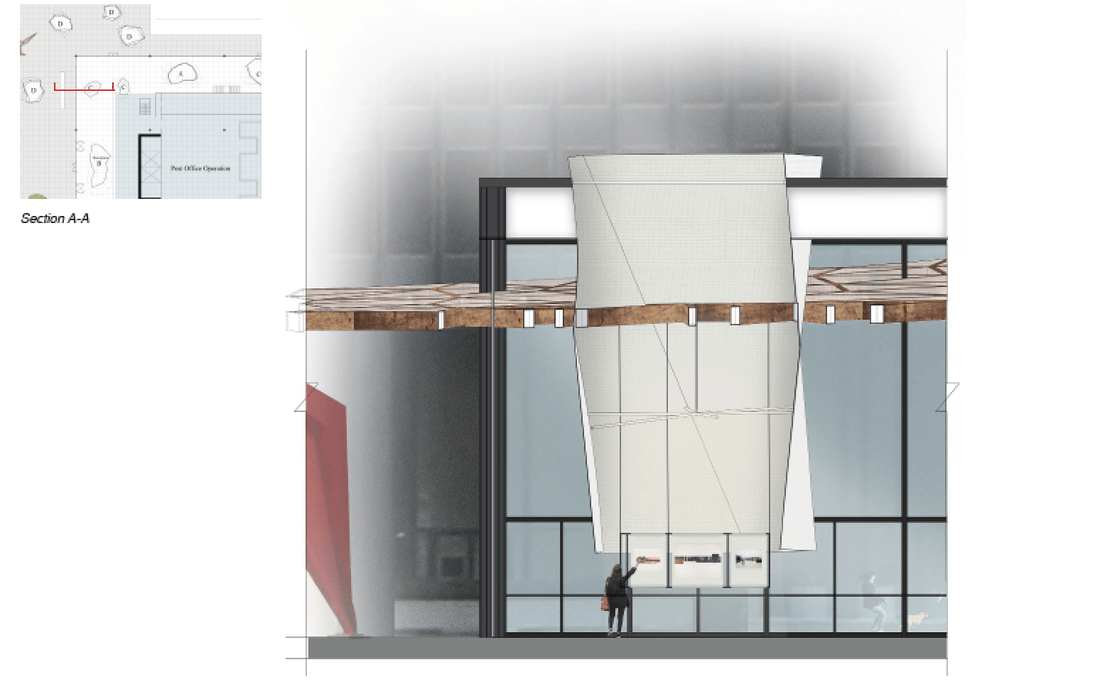

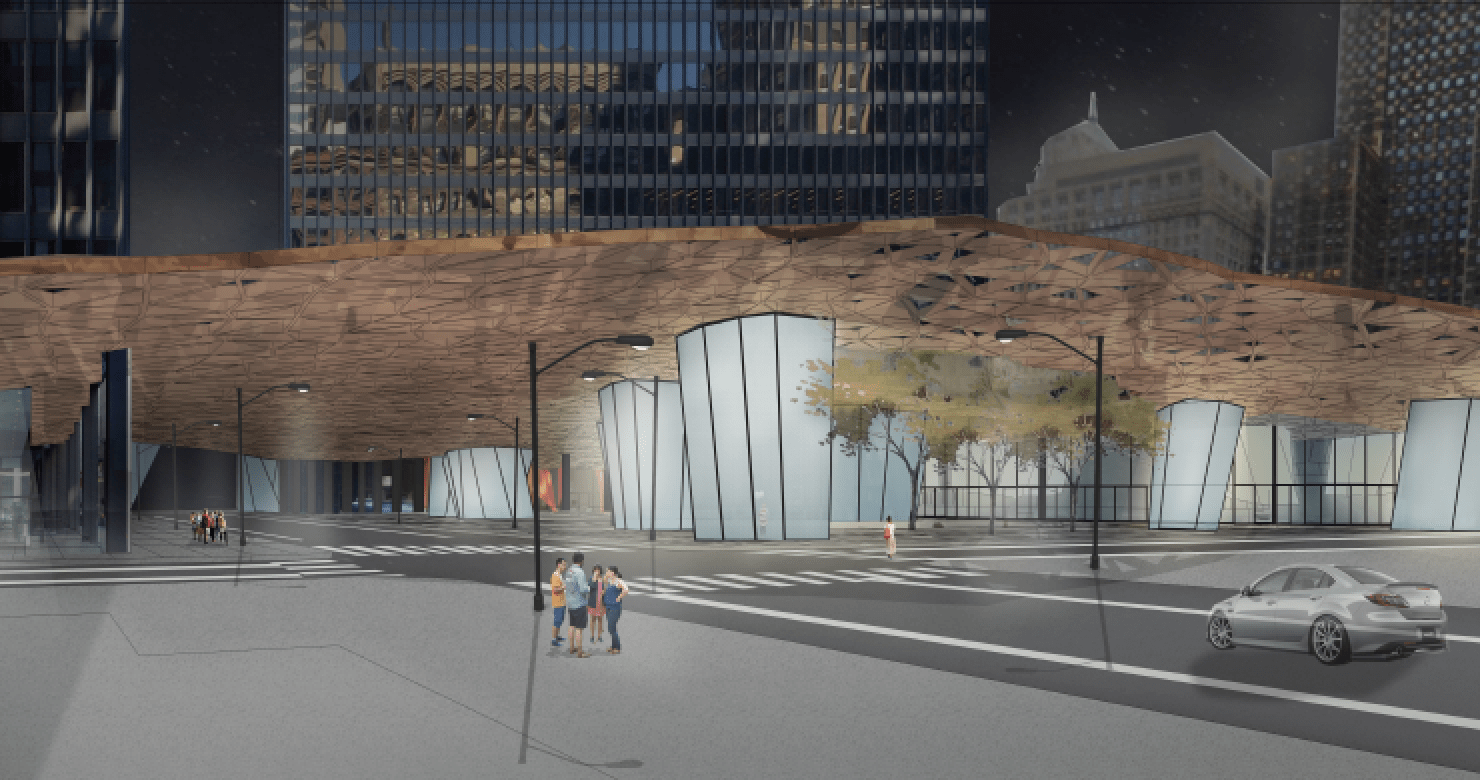

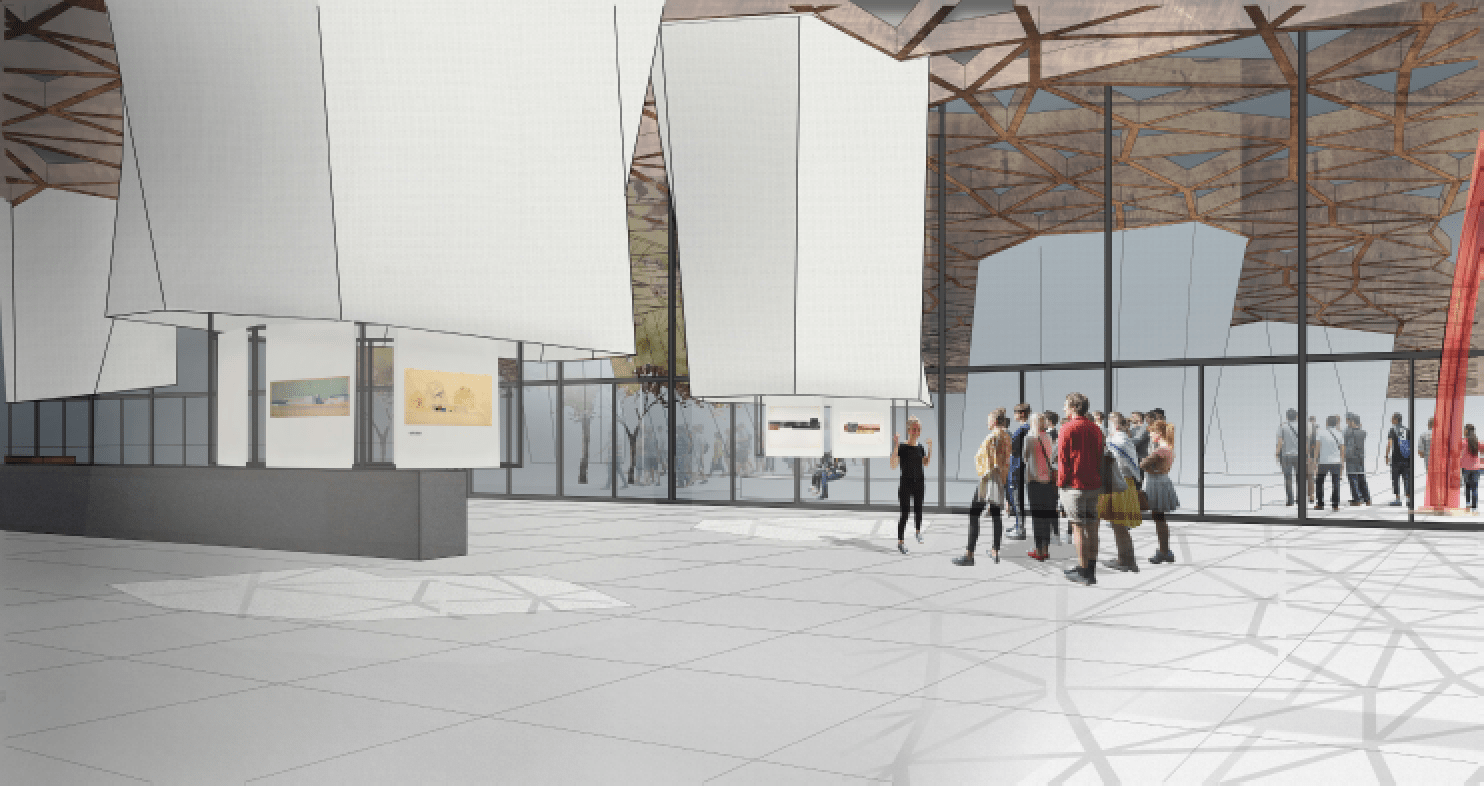

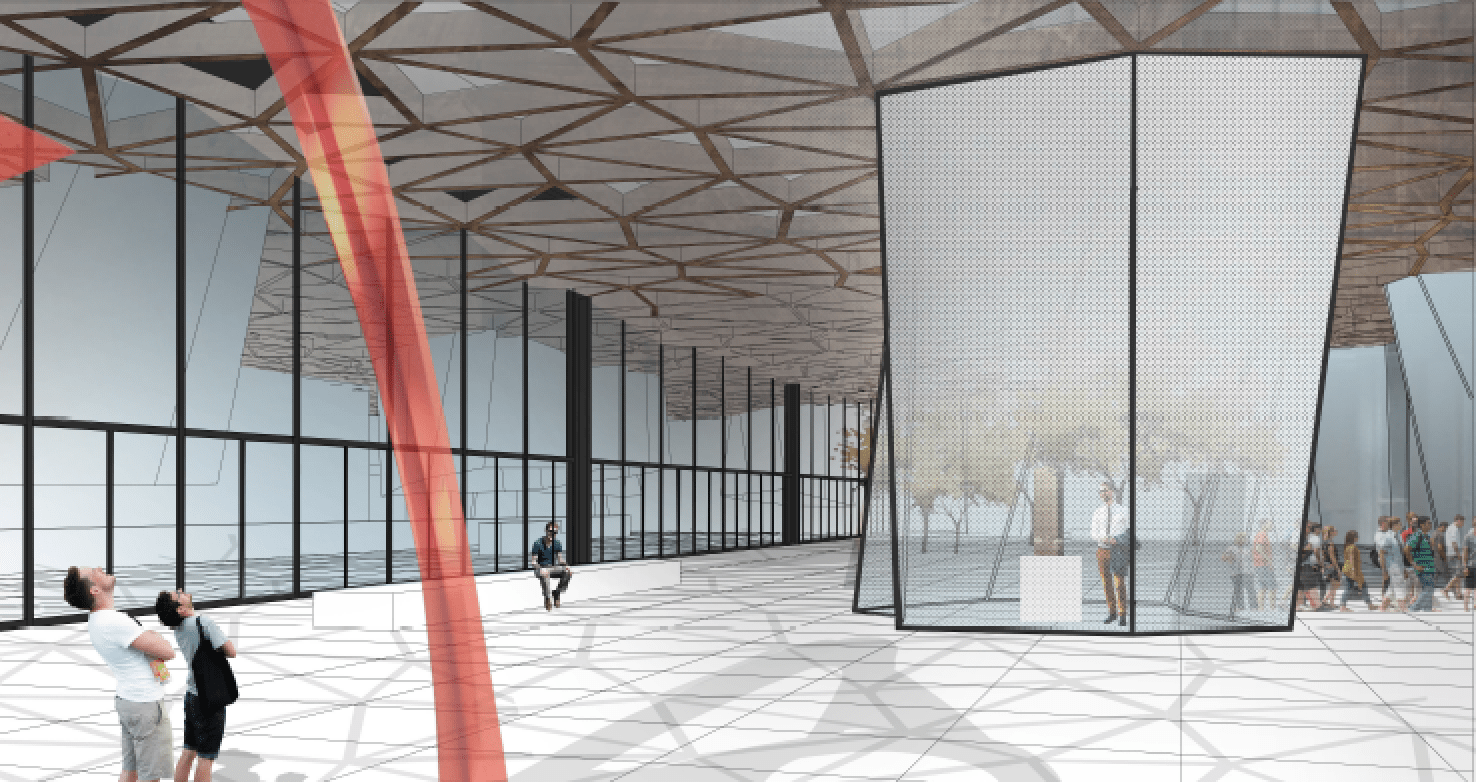

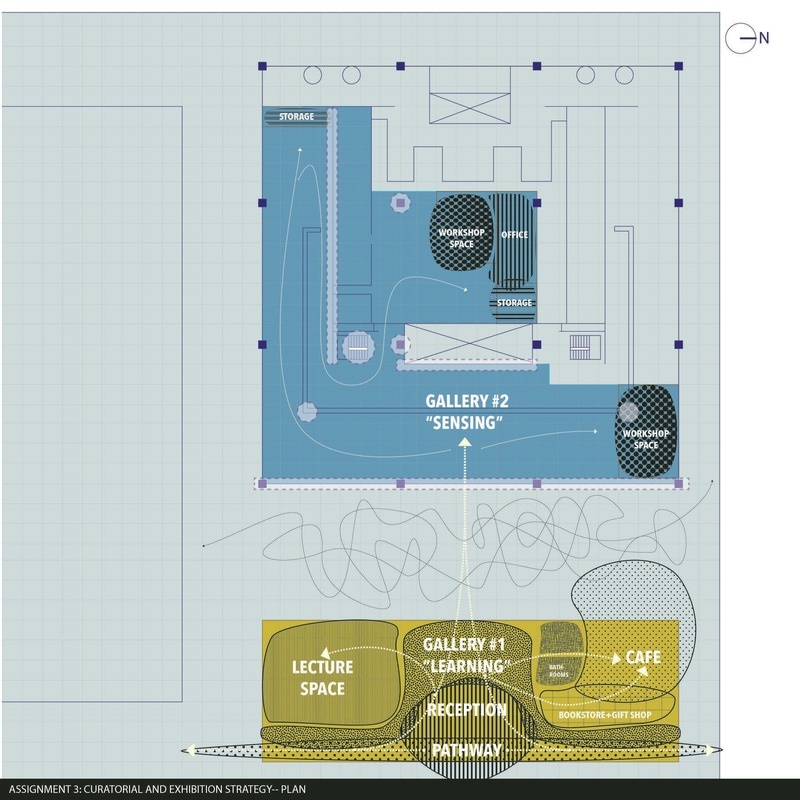

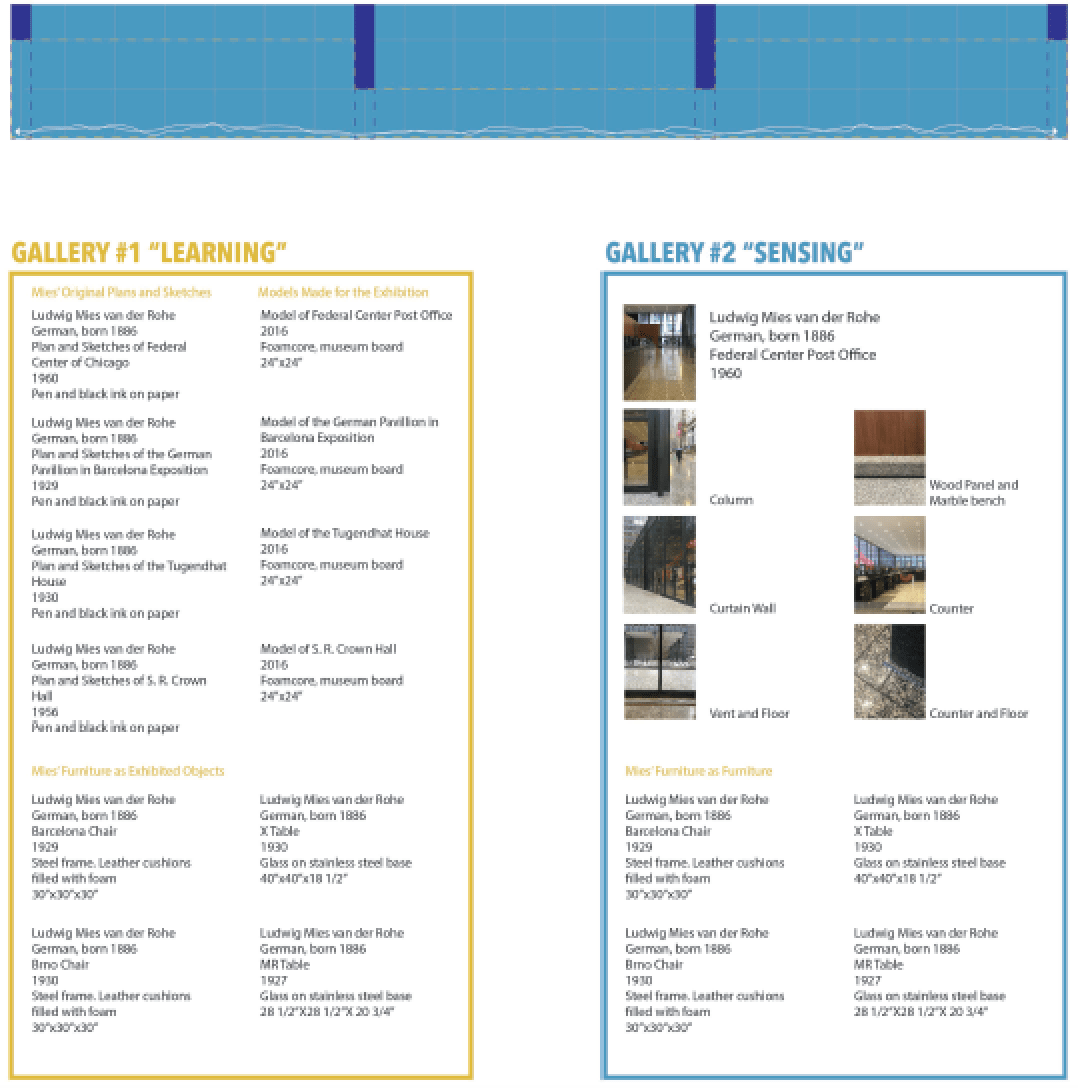

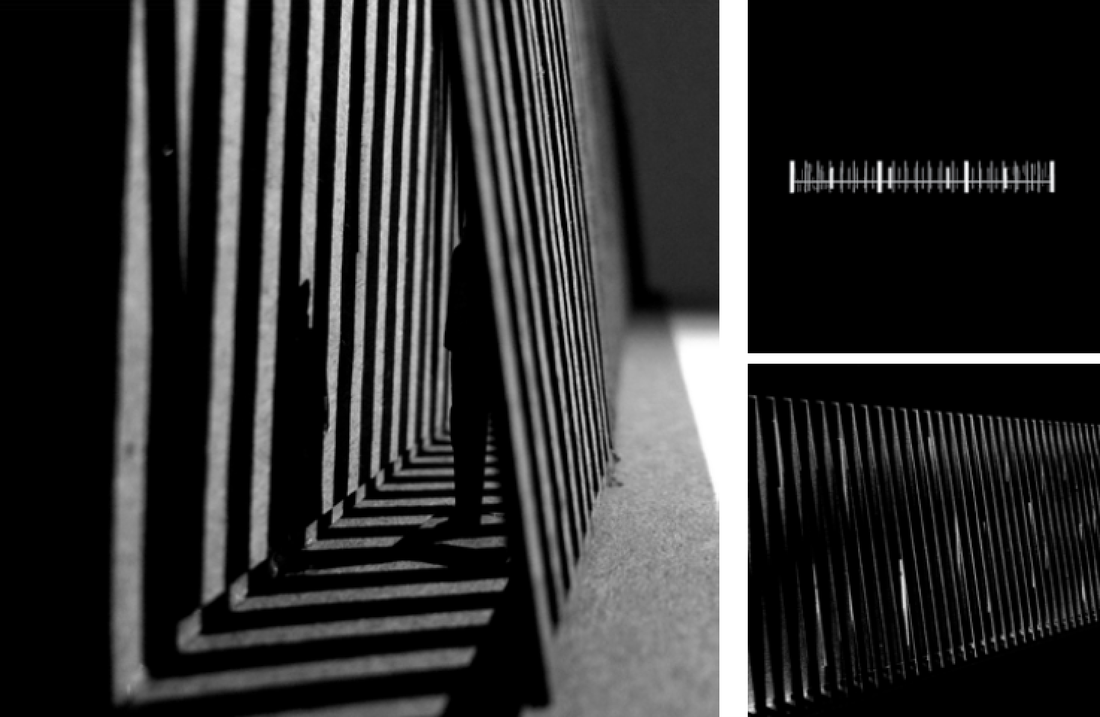

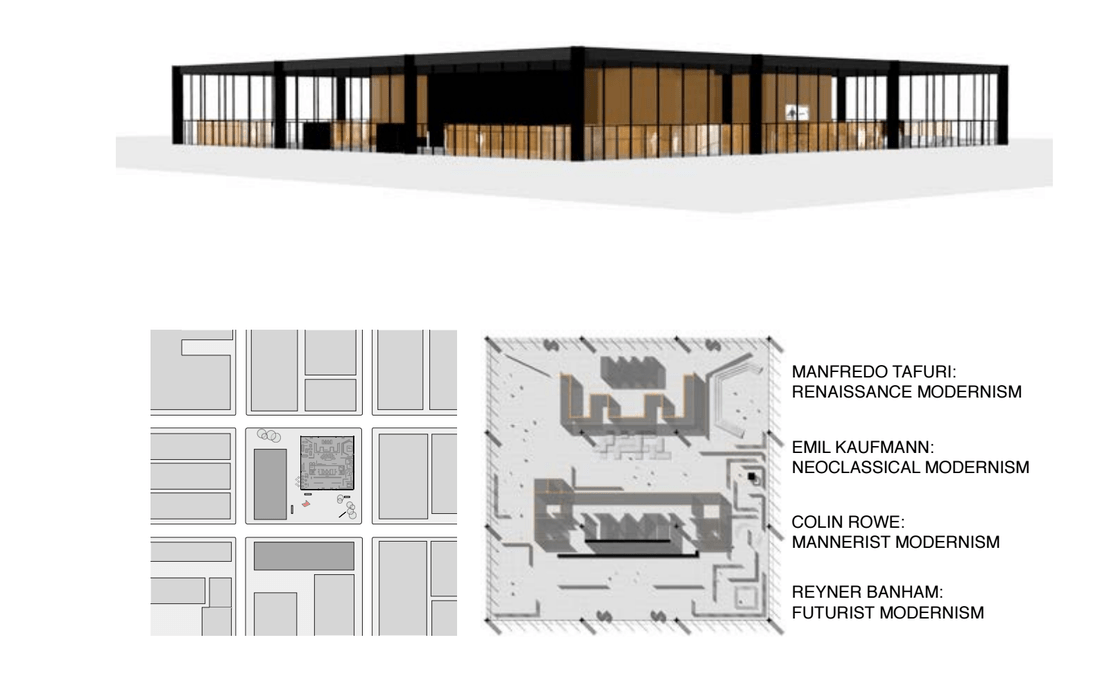

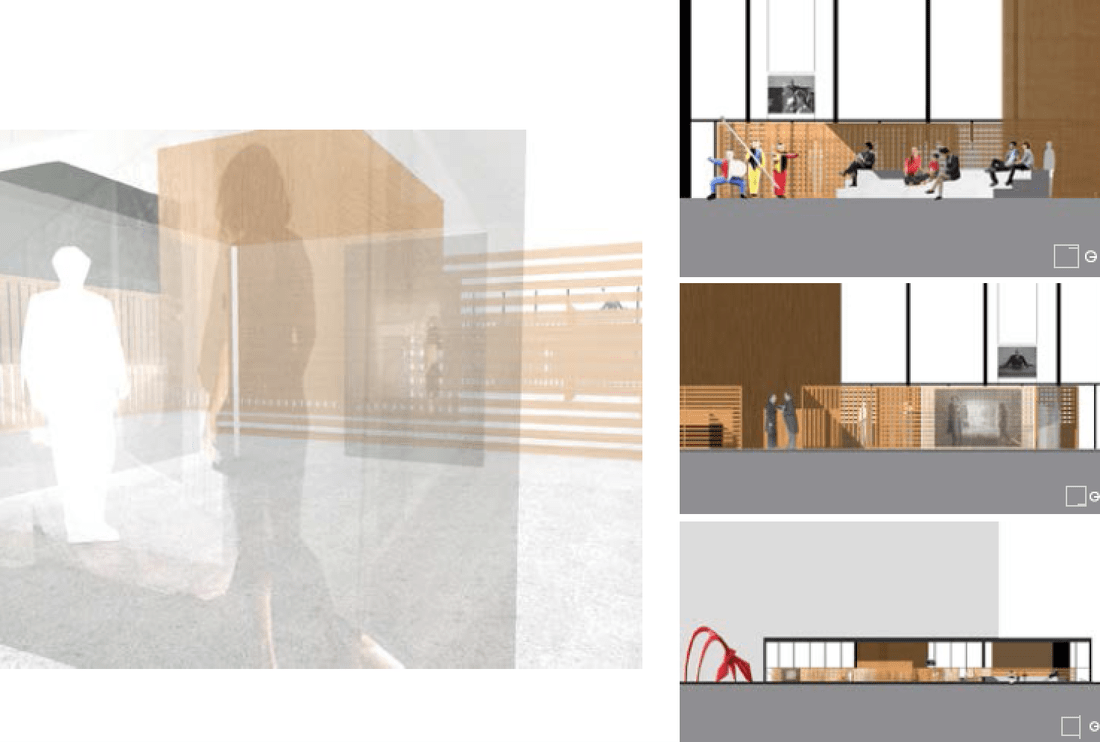

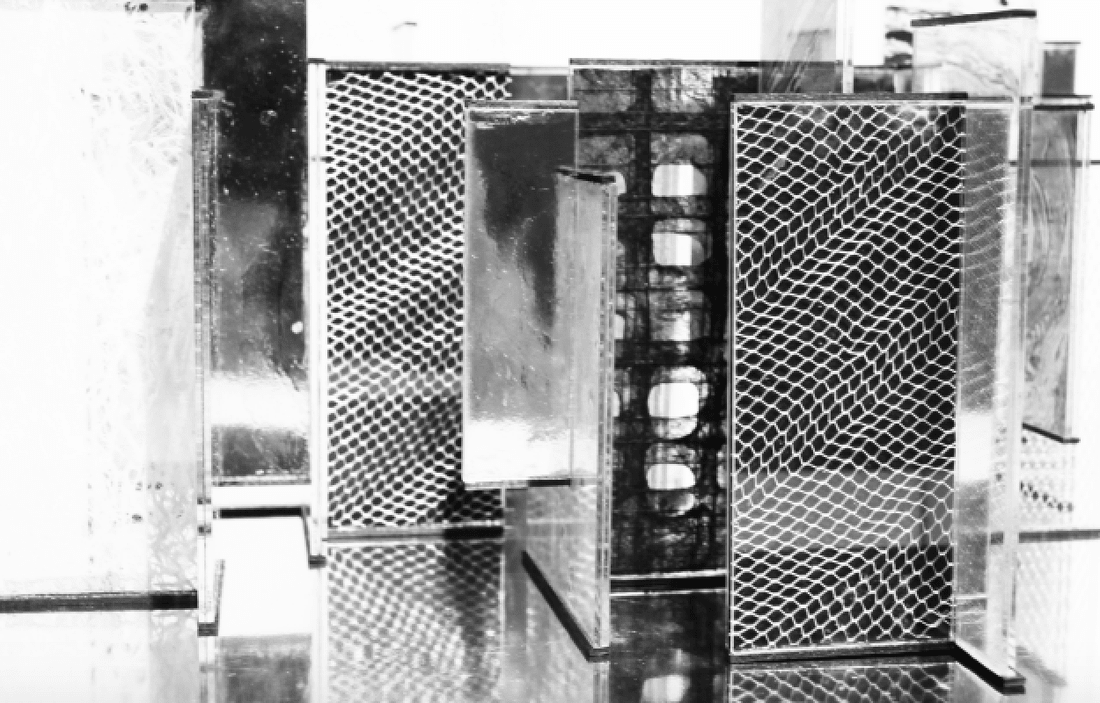

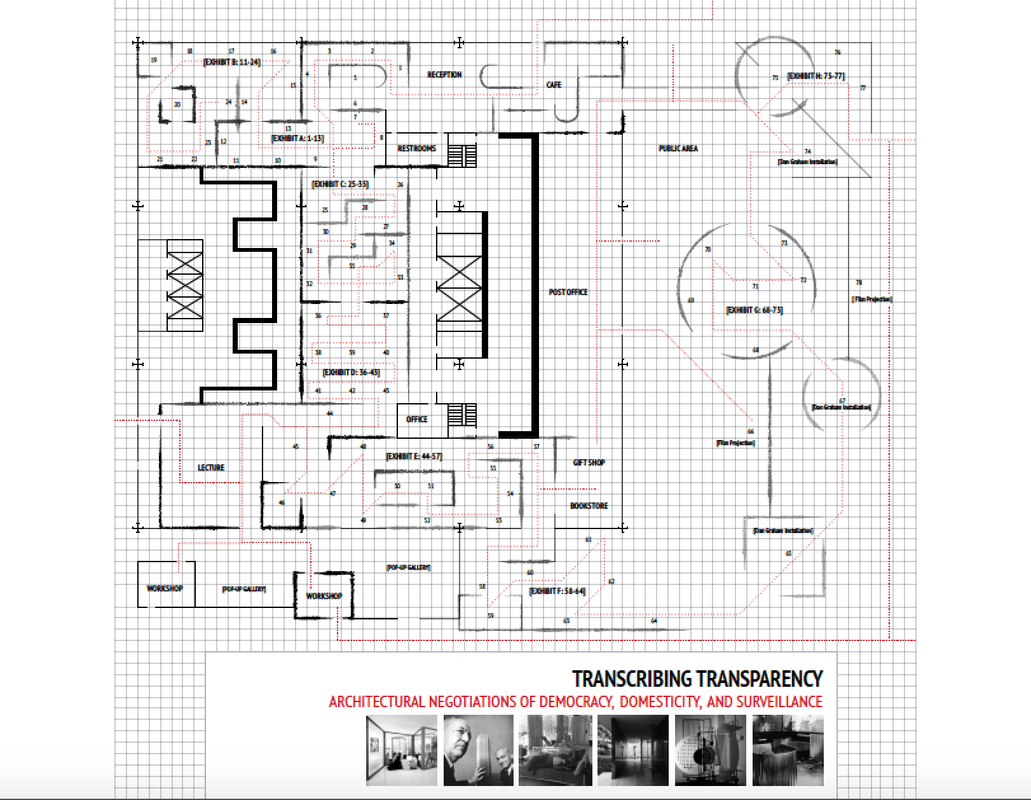

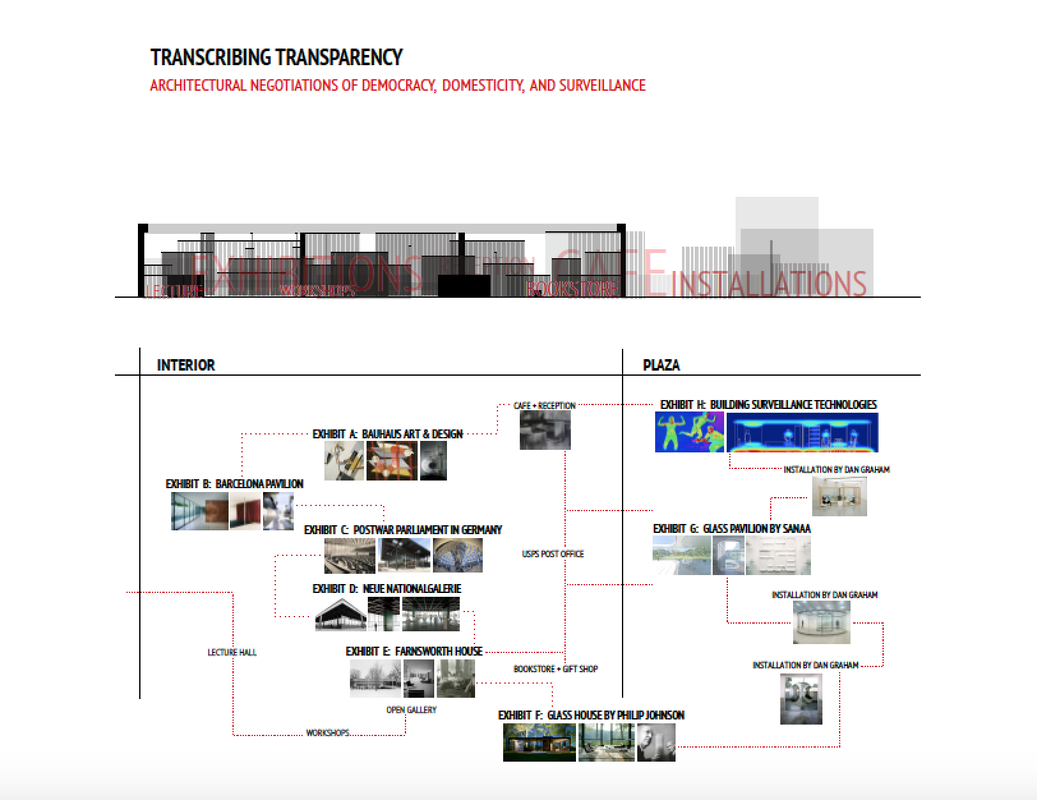

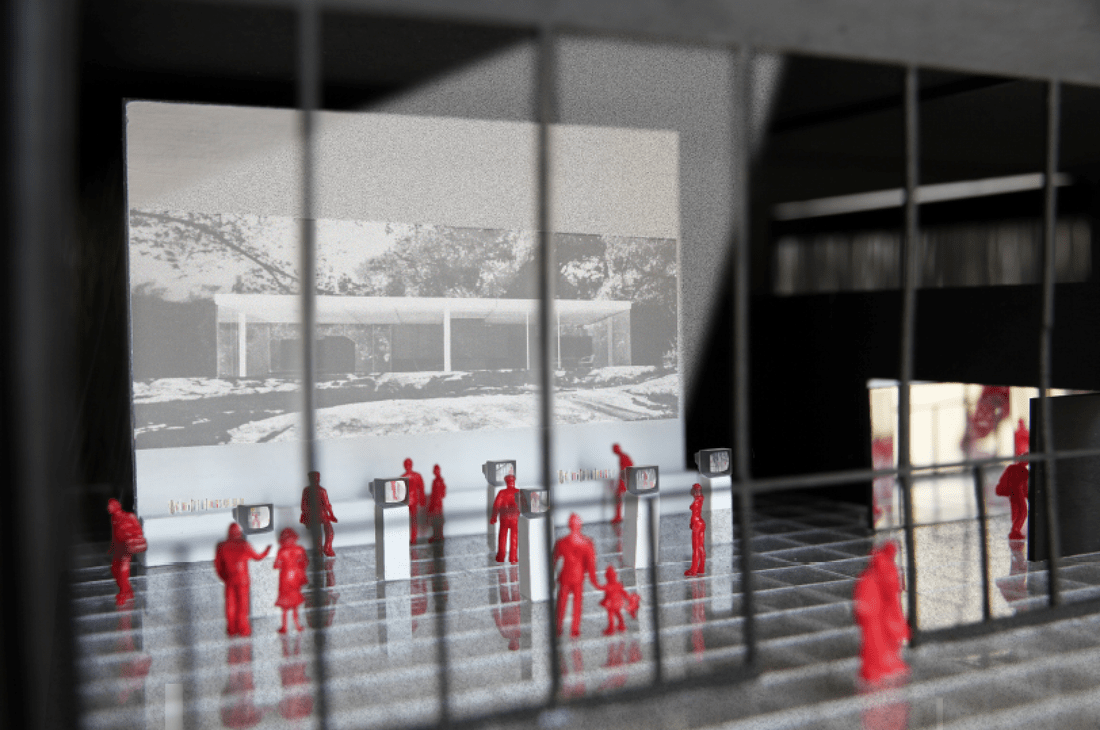

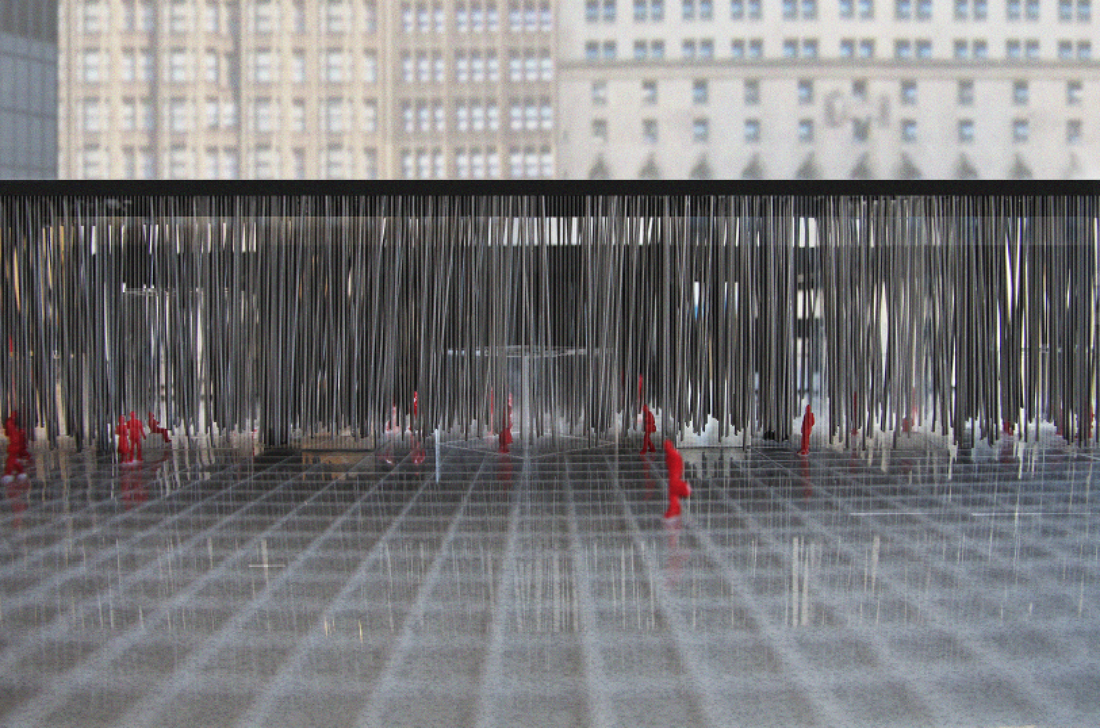

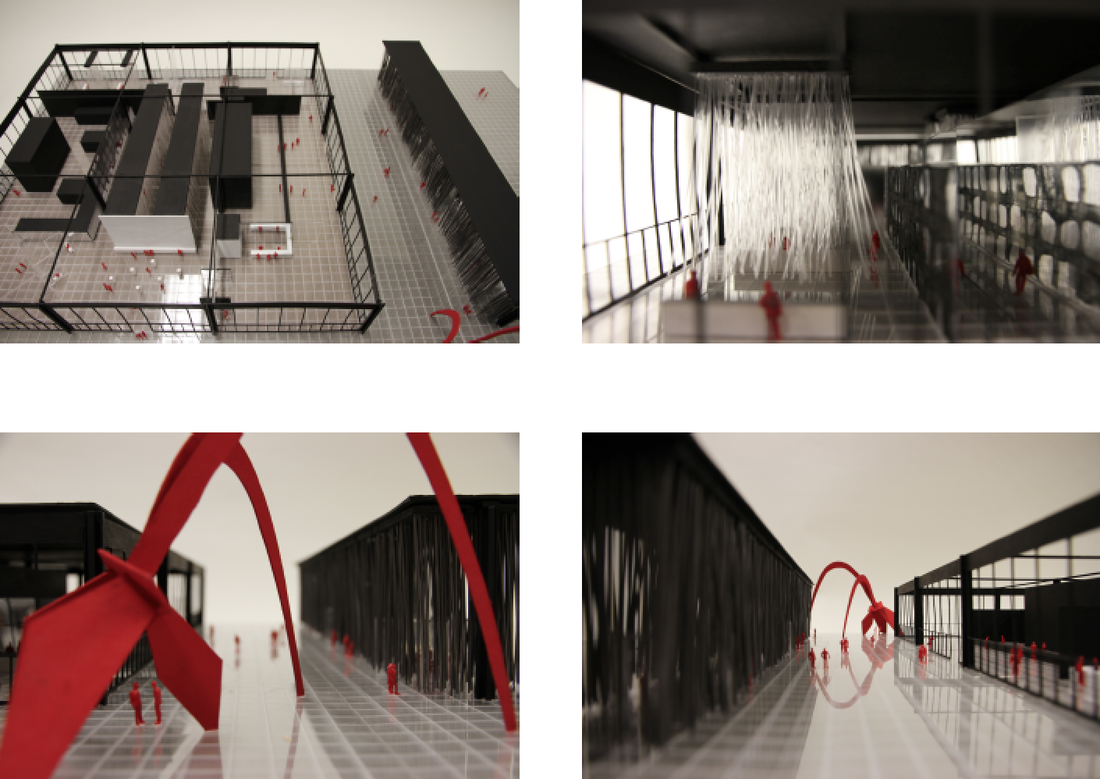

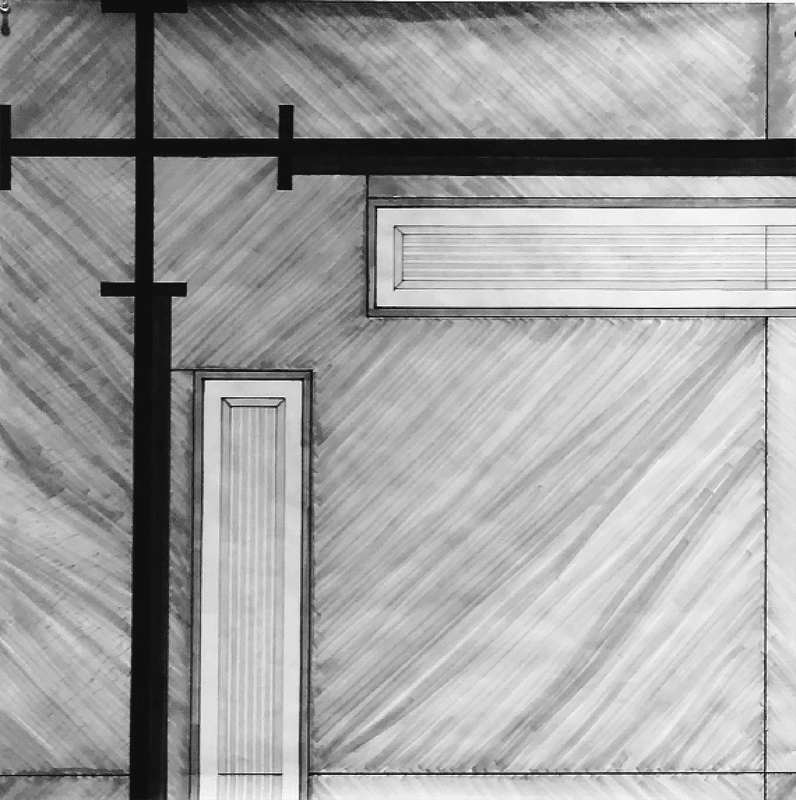

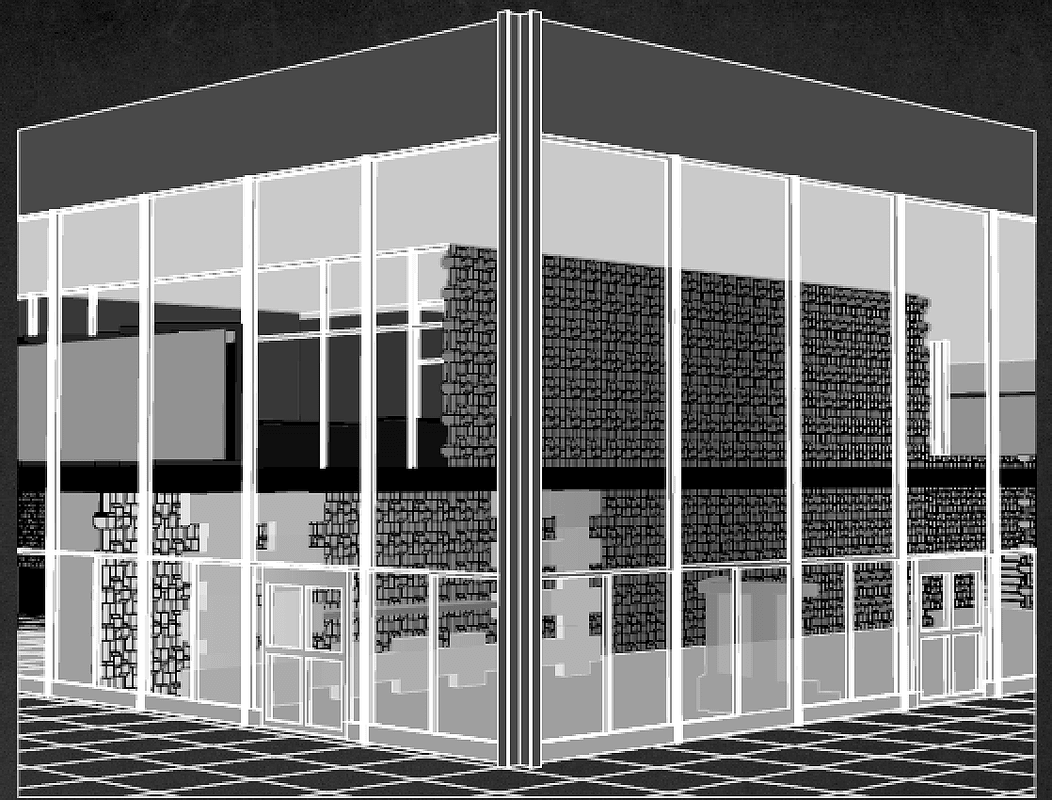

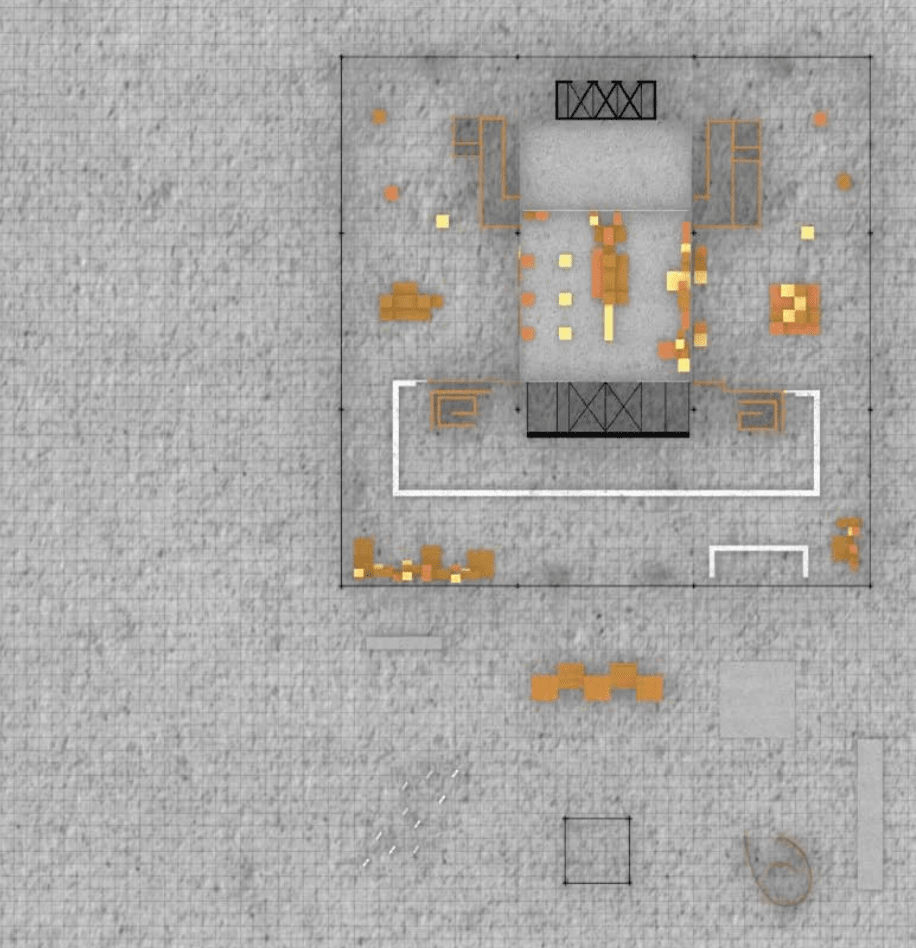

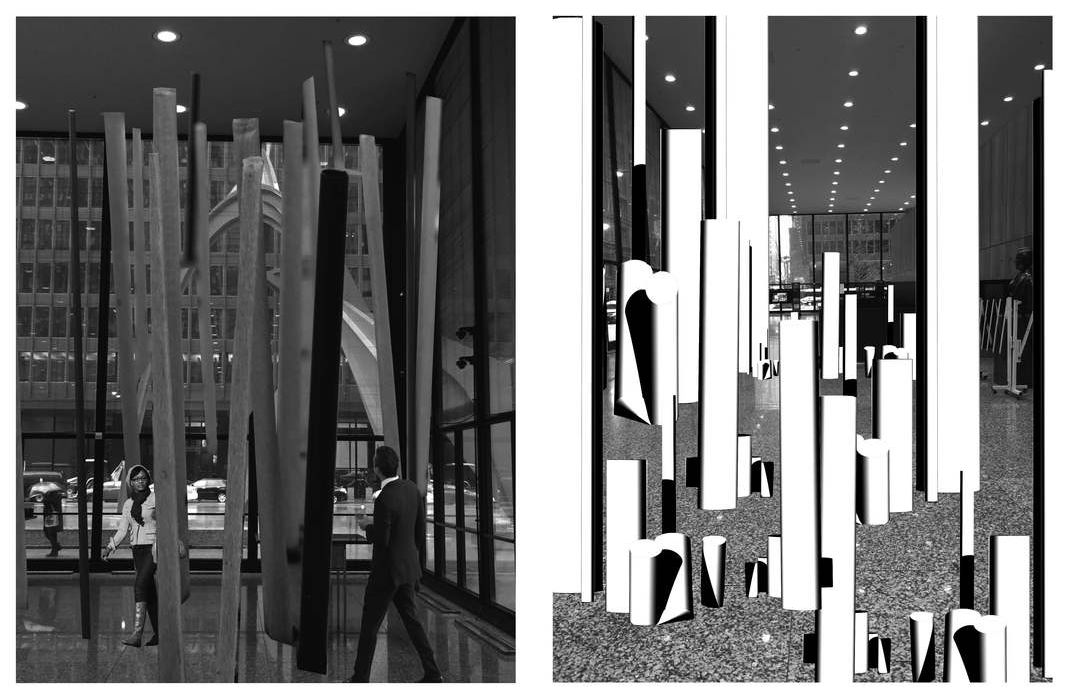

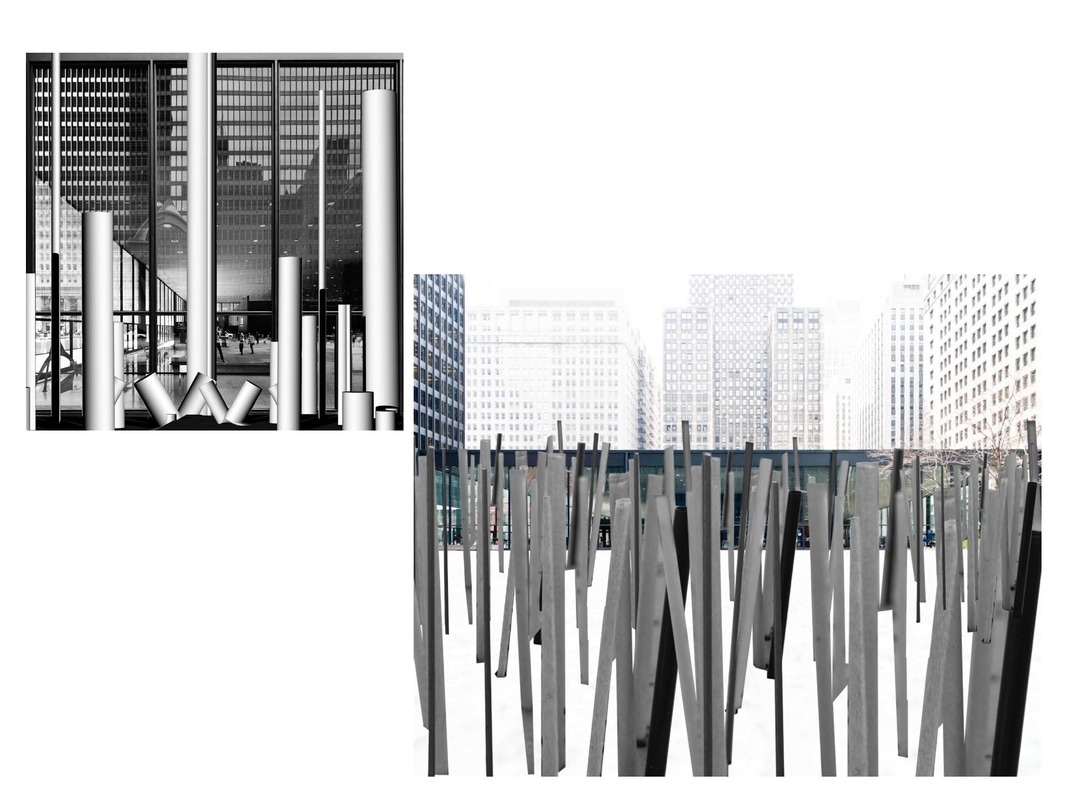

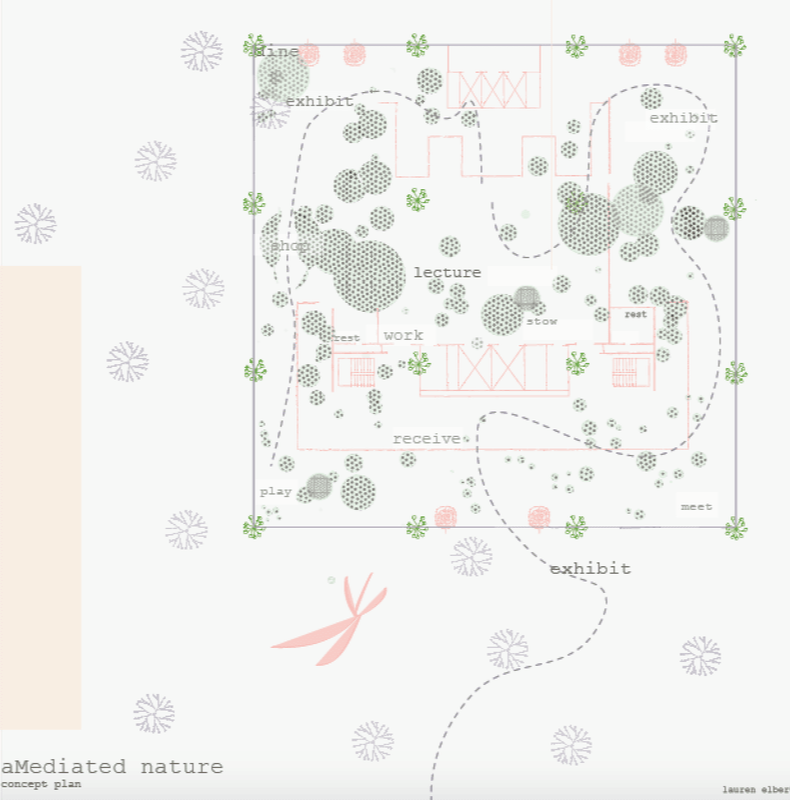

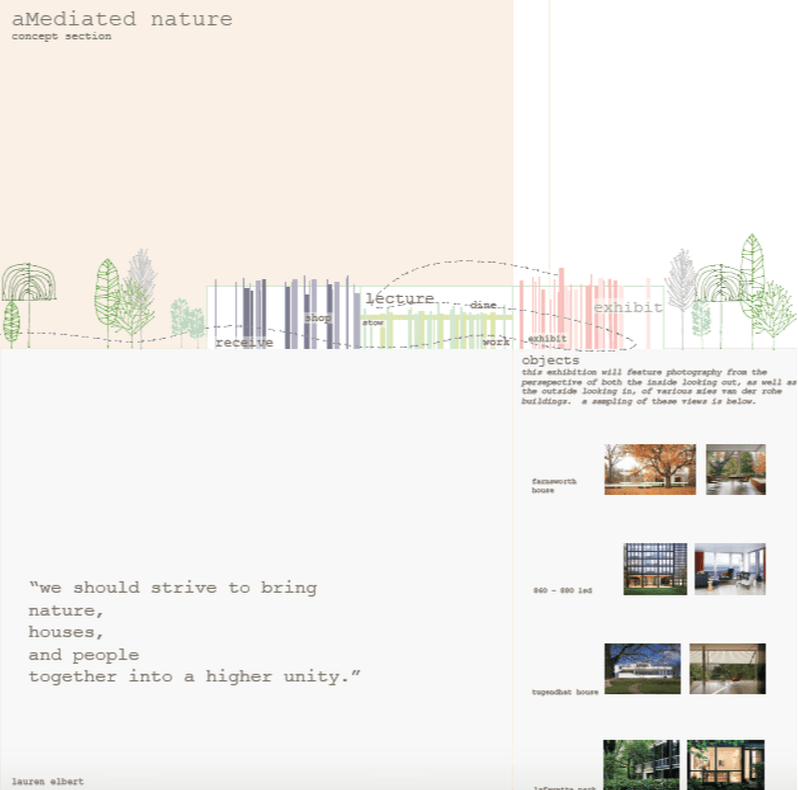

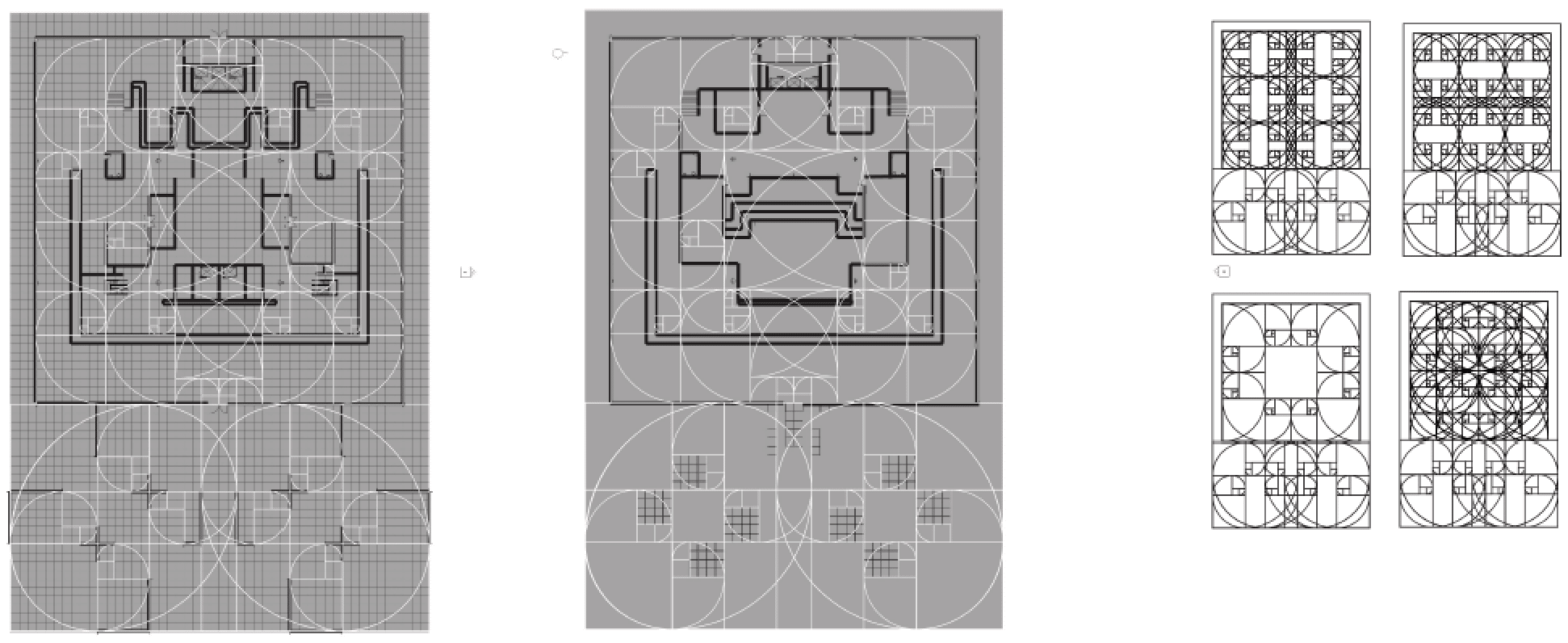

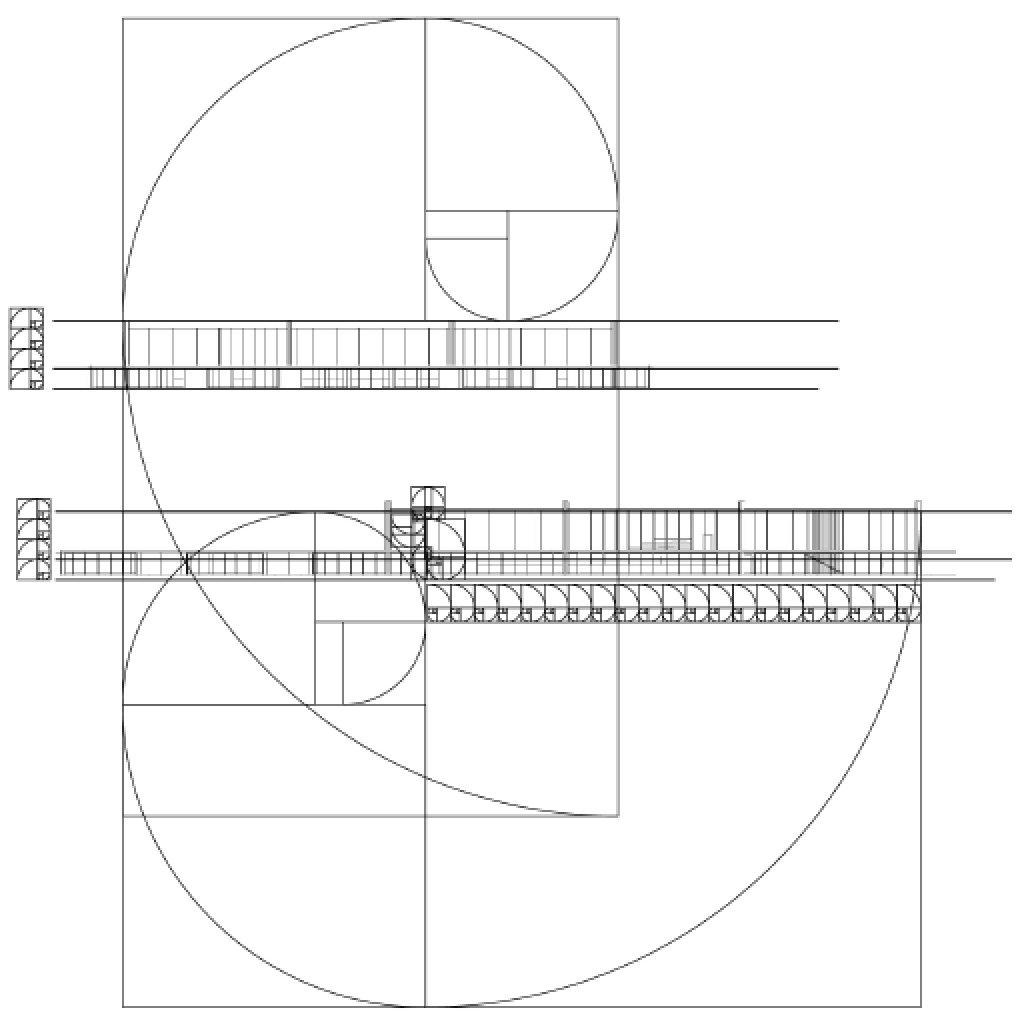

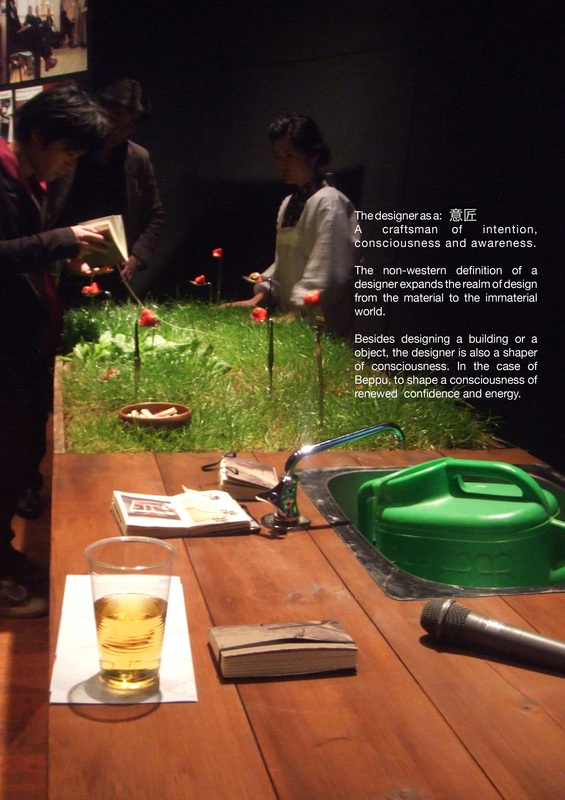

“A plan or drawing produced to show the look and function or workings of a building, garment, or other object before it is built or made” and to design is to “Do or plan (something) with a specific purpose or intention in mind.” (Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/design) A designer is therefore someone who does or plans “(something) with a specific purpose or intention in mind.” From a non-Western perspective, designer can also be called a 意匠 (Yi Jiang) The character 意, for example, carries multiple meanings- as consciousness, meaning, intention, significance, idea, sense, desire, thought and longing. As 意匠, a designer is a craftsman who shapes our consciousness and produces meaning. Through the designer’s work, our sense of the world is heightened, and the quotidian elevated to a level of significance. A designer also shapes our desires and longings. Our yearnings for homeland, justice, freedom or luxury are given material form. 意 is also made up of several ideograms- {sound (音 Ying)}, {heart (心 Xing)}, {stand, establish or set (立 Li)}, and {day, daily or sun (日 Re)}. On the other hand, 匠 or craftsman consists of 2 ideograms- 匚 (Fang), which means a box, and 斤 (Jin), which is an axe. The combinatory meanings of 意匠, from the elemental to the extended meanings offer a much more expanded role that a designer can take in contemporary society. First and foremost, a designer needs to be attentive to sound (音 Ying) in the design process. It refutes the primacy of the visual, especially when the design process is much more screen-based now. From (心 Xing), we know passion, generosity, emotion and empathy are as important as skills and techniques, while (立 Li) suggests that design is a setting in place, whether the outcome is a piece of furniture, a book or a neighborhood. (日 Re) reminds us that as a designer, we need daily devotion and a dedication to the continuing refinement and learning of our craft. Our tools, 斤 (Jin) are housed in a box that affords mobility. It echoes how our hypermobility of ideas, people and finances in the 21st century has given rise to a globally situated design practice. Mies’s Loop Post Office in Chicago provides an exemplary building for the study of skins in architecture. The building’s large steel beams painted matte black are separated from the non-load bearing exterior walls, which are full height glass and stretch along four sides of the building. The walls are only broken up only by the steel I-beam mullions. The glass façade reduces the perception of weight while accentuating the building’s transparency. Its materiality alludes to the thin, light and diaphanous qualities that one would associate with skins. The separation of the load-bearing structure and the non-load bearing enclosure has afforded enormous freedom for the exploration of architectural space in the 20th century. The building skin, on the other hand, becomes a surface opened to investigations through the various strategies of material, perception and programmatic thickenings. The opportunity for discovery is vast. Lina. Inside Mies's Mind. Tyler. Transportable Skins. Rebekah. The Ghost of Mies. Alex. Mies and Movements. Melis. Trangressing Mies. Suzie. Sensing and Learning Mies. Jordanna. The Four Modernisms. Olive. Transcribing Transparency. Molly. Capturing Corners. Dana. Mies and the Weathering in Time. Lauren. aMediated Nature.

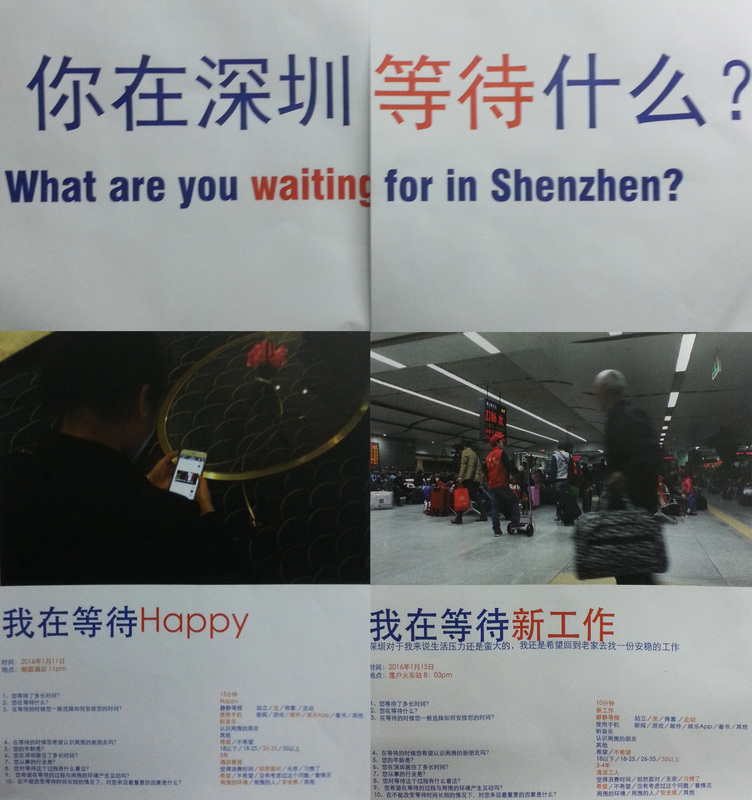

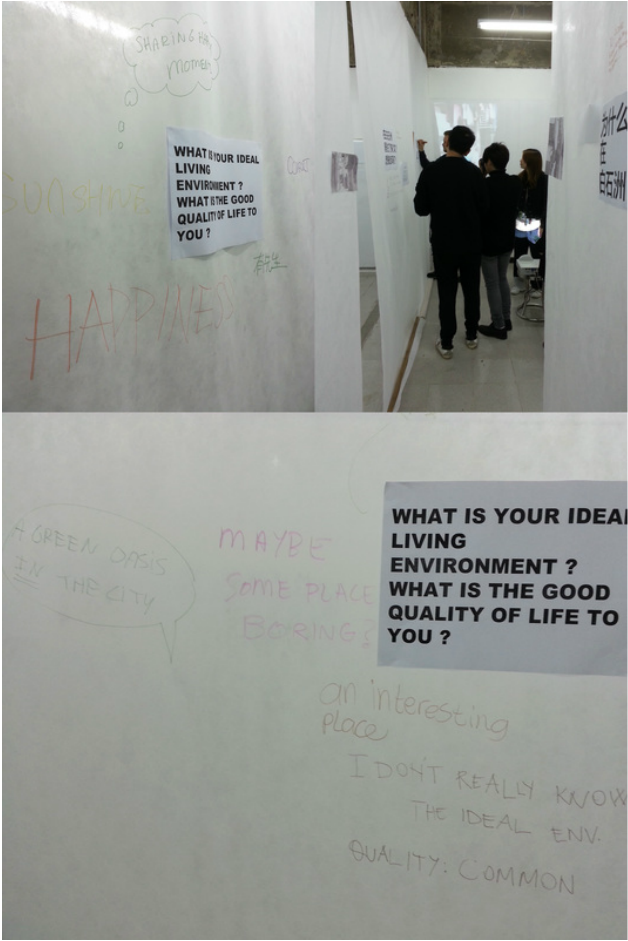

Learning from Shenzhen: The City as a Studio, was conceived and led by Thomas Kong. It formed part of a series of studios organized by the Aformal Academy during the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture. In this 5-day studio, participants were involved in a number of micro, on-site investigations centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in China’s first Special Economic Zone. Waiting Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work. Uniform The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority. Good life Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond. Form follows signage Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage. Shenzhen Vending Machine Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, the body and human relationship. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired. Drawing Memories

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life. Architecture possesses a surplus.

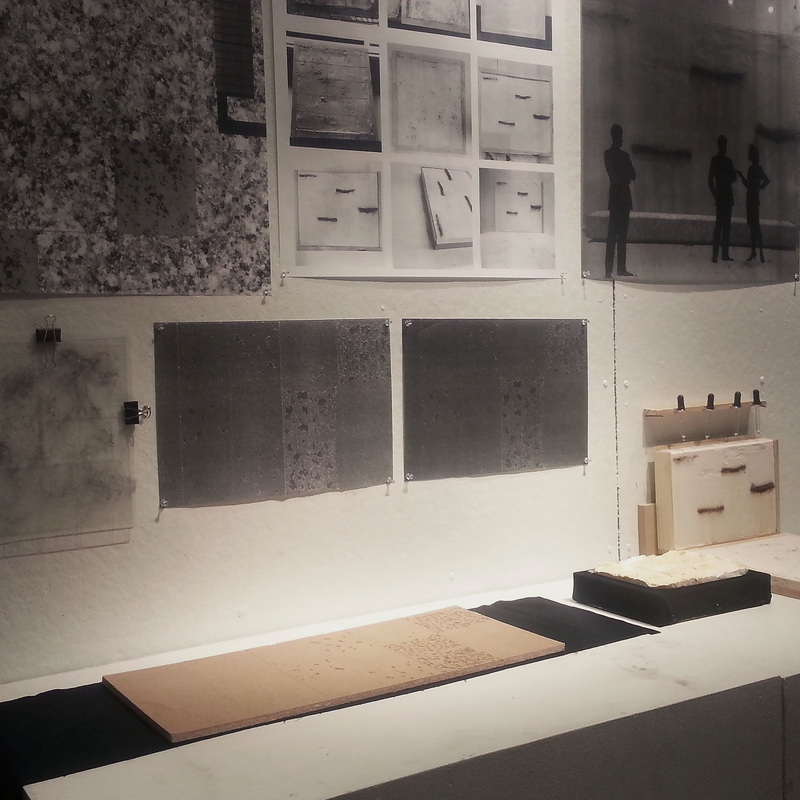

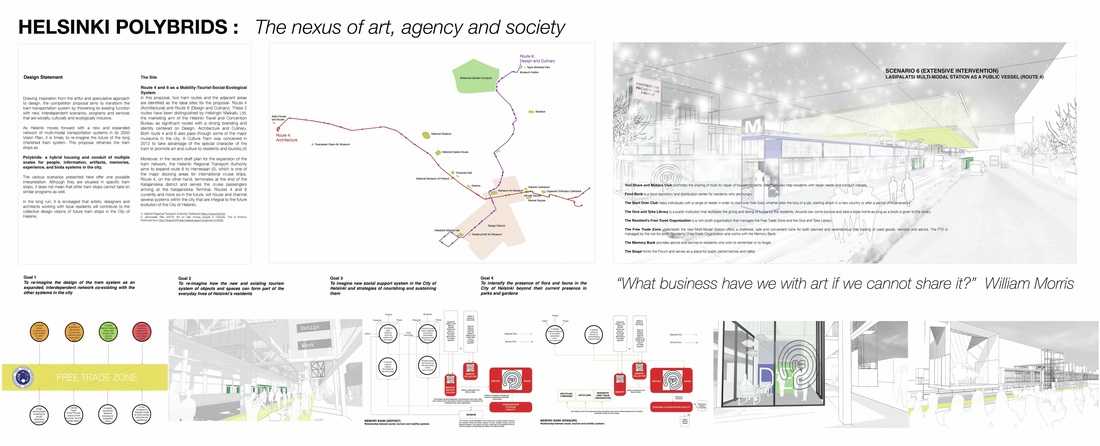

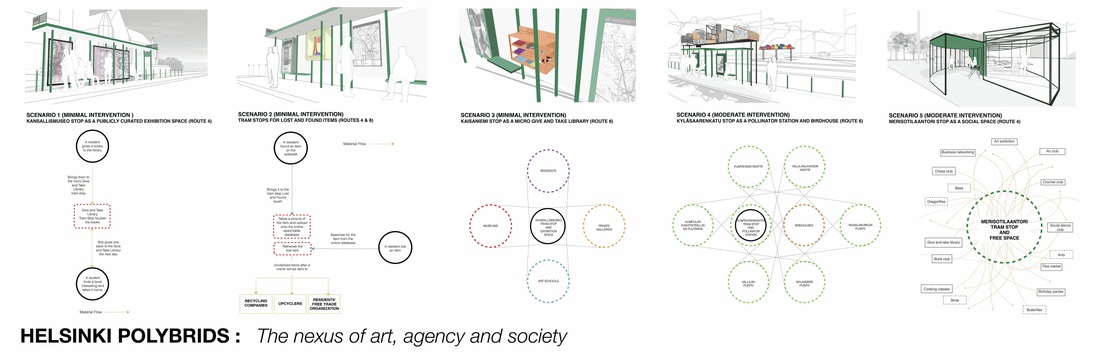

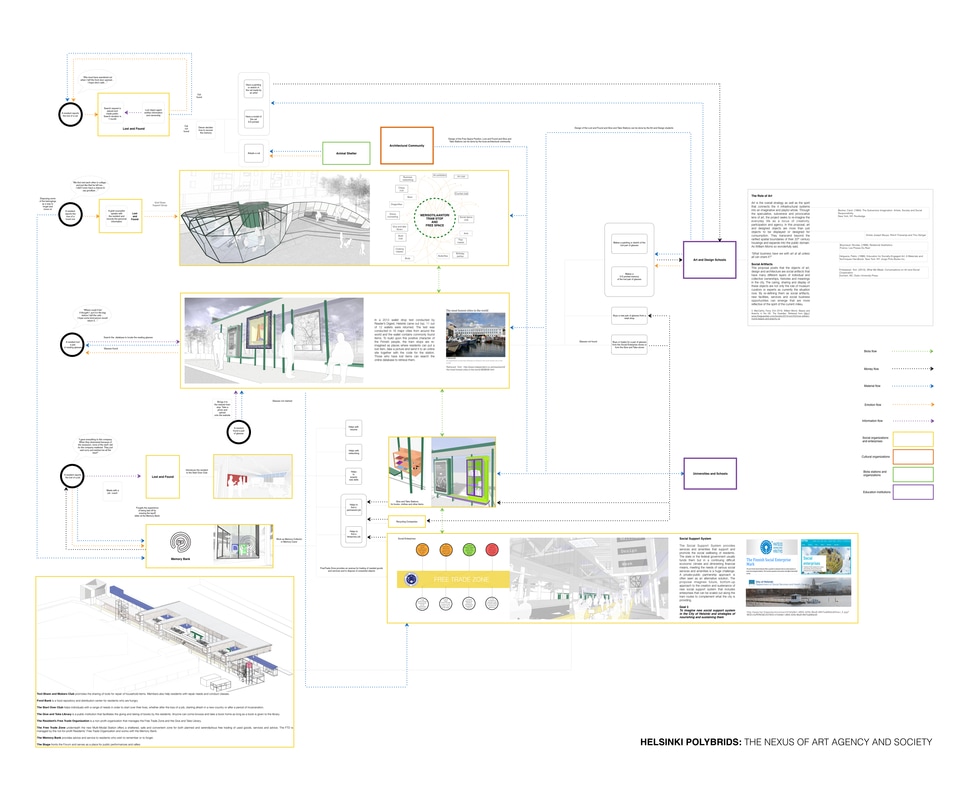

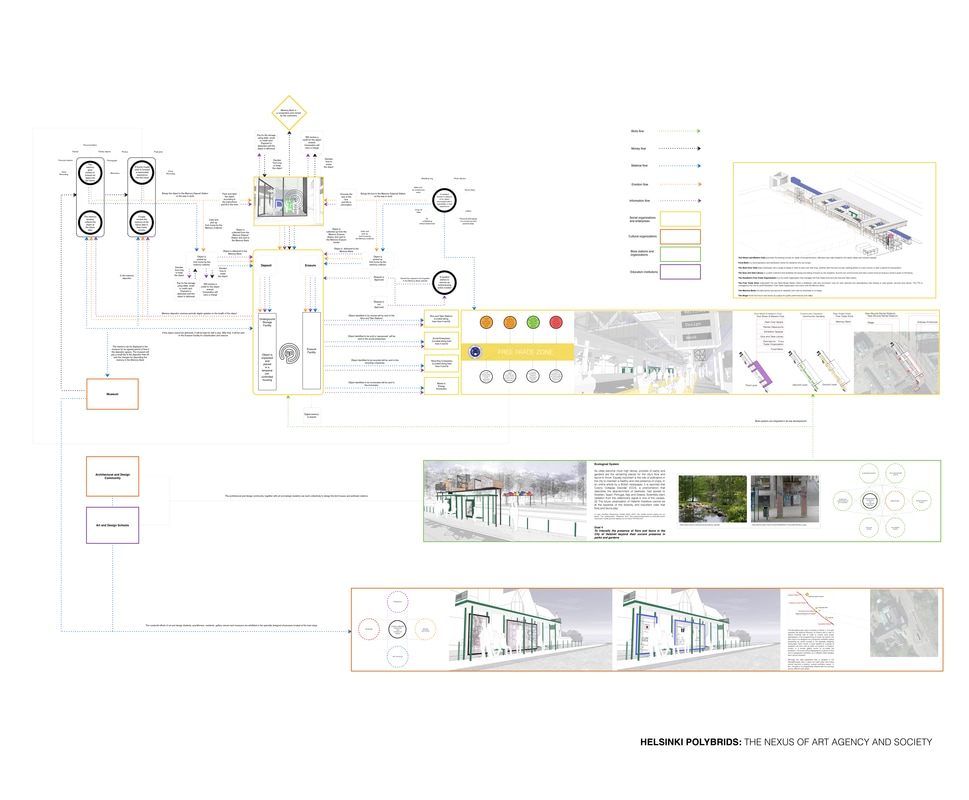

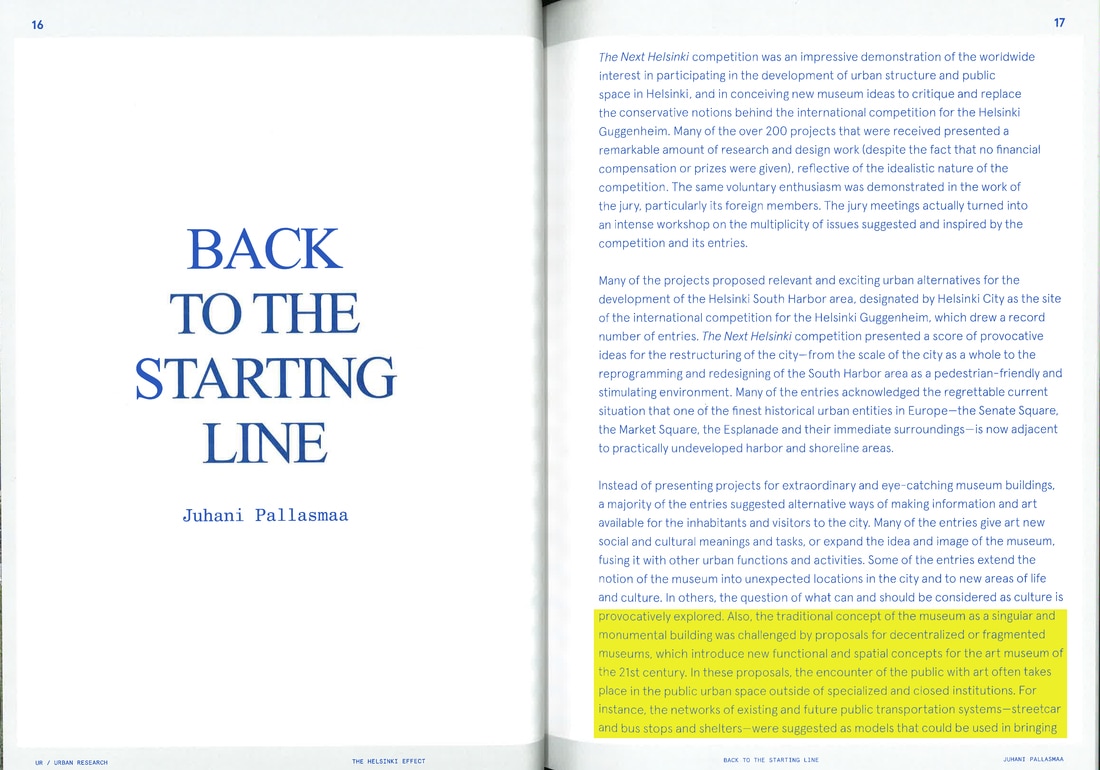

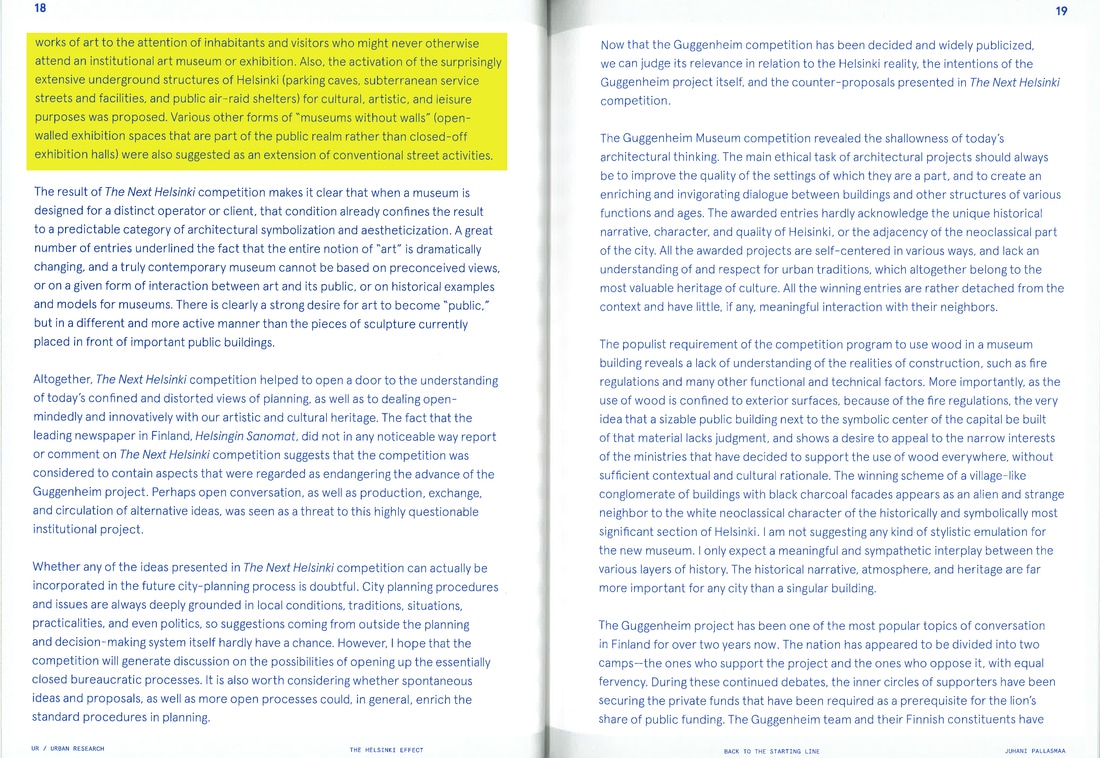

It possesses a generosity beyond designing a building or the artifact itself. This surplus is what gives meaning to a building and permits architecture to exist in other forms and media. It reminds me of a statement that one can ‘do’ architecture without designing a building. Or when the late Raimund Abraham said that to be an architect, all he needed was a pencil and a piece of paper. Whichever journey one takes, the quest for architecture has to begin with the architect and no one else. In fact it begins with the education of an architect. It begins with a search- by questioning fundamental aspects of the human condition both historically and contemporaneously because architecture is material form and space that articulates the human condition in all its failings and goodness. Recall the Nazi’s use of architecture in the expression of its warped, destructive and horrid ideology. On the other hand, see how Gaudi strived to embody the highest spiritual aspirations in humanity through his yet to be fully completed Sagrada Familia or John Hejduk’s poignant depictions of loss, remembrance, desire and love in his powerful drawings of angels and their housings. The search has to manifest into an act (not necessarily in designing a building) and must be carried out with sensitivity and empathy because architecture must be an affirmation of what is ethical and all that is good about humanity. Sometimes the action demands the architect to resist or subvert. In other moments, to strengthen, protect and shelter. The architect constructs a world. By this, I mean the architect structures and orders spheres of human experience through the thoughtful and intelligent use of media. The process is as much influenced by the character and propensity of the media as the inner voice of the architect. It is a voice that is first recognized and nurtured while in architectural school and matures through the life of the architect. It is shaped by cultural specificities, personal experiences and reflections, which re-emerges from the architect in in myriad forms and ways. Donald Schön notion of the reflective practitioner echoes this act of design that is informed by a continuous feedback loop of reflection, understanding and action. Each stage of the process moves from confronting something new in the beginning, drawing from one’s past experience in probing, testing and transforming the initial condition while creating a new understanding for the architect. It is a process of educating oneself. In other words, the life of an architect’s education is inexplicably linked to the architect’s process of understanding and awareness of his or her place in the world, which does not stop after graduation but continues into the professional world. It is a lifelong process of questioning and searching that marks the arc of an architect’s growth and development. "Helsinki Polybrids: Nexus of Art, Agency and Society" has been recognized by the jury panel of the Next Helsinki international architectural competition chaired by Michael Sorkin. Among the jury members are Juhani Pallasmaa, Walter Hood, Sharon Zukin and Mabel Wilson. There were over 200 entries from 40 countries. ”Almost like a dictionary of human thought and collective imagination.” (Free quote from jury member Juhani Pallasmaa) https://www.facebook.com/TheNextHelsinki 'Almost everything in the world today is mobile. Why should art be static?' Juhani Pallasmaa #NextHelsinki https://twitter.com/CheckpointHki https://homes.yahoo.com/news/adventures-architecture-next-helsinki-adds-212325775.html http://www.nexthelsinki.org/ My shortlisted proposal and the other 200 over entries form a collective and creative counterpoint to the corporate driven art market initiative of the Guggenheim Museum. Our proposals are part of the major debate over the long term value of the Guggenheim Helsinki project, which has faced massive push backs from Finnish citizens and prompted the setting up of an alternative international architectural competition. Since the Great Recession, city officials are realizing that big, iconic projects are becoming harder to push through in parliament because citizens are demanding for greater investment in social infrastructures instead. However, to avoid financing public art is also ill-advised as it is an important contributor to the culture and economic vitality of cities. A new model of art-making, curatorial practice, presentation, support, housing and archival will need to be designed. To avoid succumbing to the seduction of another one-off piece of iconic architecture costing billions of dollars to build, exploits cheap migrant labor and requires long-term, expensive maintenance, my entry re-frames the making, curating, exhibition and sustenance of artworks as a bottom-up, community driven activity that involves a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the city. It sees economic value of art not limited to how much one can afford to pay and sell at an astronomical price later but a more socially distributive model where the ecology of production, distribution and use (and re-use) is intertwined with the everyday life of the Finnish residents. Instead of scaling up even bigger as most contemporary museums seem to suffer from these days, my entry proposes to scale-out into the different neighborhoods by borrowing the city’s existing tram lines and stops. Through the process of creating the multiple art polybrids in the city, the tram lines and stops, which serve a vast section of the Helsinki residents and are in a state of decline, get to be refurbished and renewed at the same time. This twinning of art and public infrastructure makes good economic sense. The art polybrids are also way more accessible than a singular building, and are more effective in harnessing the collective imagination and creativity of the people. Museum goers are no loner passive consumers of a paid experience. They have the power and the opportunity to co-curate, to make art and in the long run, strengthened community bonding and identity, as well as fostering a more inclusive and socially resilient society. Helsinki Polybrids: The Nexus of Art, Society and Agency is therefore designed to offer a multi-scalar, horizontally distributed, economically and socially sustainable re-framing of art, its production and experience for a 21st Nordic city. The entry was exhibited in the recently concluded Tallinn Architecture Biennale in Estonia under the Research and Development Lab, which saw 1600 visitors over 12 days. The result of the Next Helsinki Competition has also been featured in many influential architecture and design websites, and the Finnish Broadcasting Company. In 2016, the book UR: NextHelsinki by Terreform containing the short-listed entries and essays will be published to document the process and the discourse surrounding the alternative competition, which no doubt will rouse further interest and attention. Academics too, have shared their perspectives on the contentious issue. Writing on the shortlisted entries for the Next Helsinki architectural competition, Peggy Deemer (2015) wrote, “The cultural value of this competition will probably not be in the form of creative capital—although the shortlisted proposals offer excellent thinking on what makes a city work such that art can be appreciated.” (para. 9) Referring to the Next Helsinki architectural competition again, Deemer (2015) was convinced that, “its very existence as performance, display, and conversation—its cultural capital—forces the Guggenheim to scurry and scratch for its rewards.” (para. 9) Besides being in a critical moment in the global discourse to unpack, critique and contextualize the value and purpose of such lavish projects, my shortlisted entry offered an alternative model to the Guggenheim museum franchise that weaved together the art, mobility, tourism, social support and ecological systems in the city. On a professional level, my proposal is a continuation of my research on and formation of a parallel architectural practice and education model inspired by the arts. According to the Legal Information Institute (2015), the definition of the ‘the Arts’ by the United States Congress includes architecture, besides the commonly accepted artistic practices such as sculpture, painting and photography. This inclusive definition opens up the possibilities for the creative renewal of not only the architectural profession but the teaching and learning of architecture as well. The breadth and scope of design services have also increased enormously in recent decades to encompass service design, design activism and strategic design, to name a few of the new fields. The strategic design thinking and human-centered problem identification skills used by architects in their daily practice can therefore be developed and marketed as new skills-sets and services to buffer against another economic crisis. Fluid/Soundings in London and AMO in the Netherlands are excellent examples of such an interdisciplinary practice. On the other hand, the nomination of architecture collective Assemble in the U.K. for the 2105 Turner Prize in Art is a strong endorsement of design activism and the art-design nexus of contemporary spatial practice. In my conversation with a design strategist working in the multidisciplinary American architecture firm Gensler, it was very clear to her that their major clients are not only interested in just a well designed and sustainable building but also a strategic vision that aligns architecture with social and business innovations, as well as environmental stewardship. Architect Michael Sorkin, the organizer of The Next Helsinki architectural competition puts it most provocatively when he declared in an interview with the U.S. based Metropolis magazine, “We invite competition entries from any and all, includes any of the 1,700 losers from the Guggenheim competition whose work looks beyond simply building a museum on the site.” (M, Sorkin, personal communication. Jan 22, 2015). Reference Deemer, Peggy. (2015).The Guggenheim Helsinki Competition: What is the Value Proposition? Avery Review: Critical Essays on Architecture. Issue No. 9. Retrieved from http://www.averyreview.com/issues/8/the-guggenheim-helsinki-competition Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from Cornell University Law School site https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/952 Revised drawings showing the ecology of existing infrastructure, education and cultural institutions, social agencies and parks as spaces for art making, sharing, presentation and community engagement. Architect, Professor and competition judge Juhani Pallasmaa's acknowledging the Helsinki Polybrids entry in his essay, Back To The Starting Line.

Gaps are everywhere. Some exist because of poor workmanship, a result of weathering and use or are designed as tolerances between materials. We have different ways of dealing with unwanted gaps. A gap between the leg of a table and an uneven floor is usually mitigated by a paper shim while a gap in a wooden window frame is lined with caulking and painted over to conceal it. One would commonly associate a gap with a space that is narrow or small but a room can be argued as a gap too, albeit one has been expanded to accommodate human activities. Unlike the unwanted small gap, we would not want to completely fill this up. We need this gap to exist so that we can live, even though we tend to pile it up with our stuff, memories, desires, fears and hopes. We feel safe too, in this big gap. It keeps us warm in winter and cool in summer. It keeps out the rain, the noise and strangers, although now virtual strangers can share the same gap with us remotely. Further expansion of this room-gap would result in a series of even larger gaps called a house, a neighborhood and a city. Within these larger gaps are smaller ones that co-exist with and sustain them. A storm drain is a linear gap along the street to channel rainwater away, which would otherwise flood the street if left alone. A gap between two tall buildings allow light to stream to the ground, which otherwise would leave the street gloomy. Narrow gaps called alleyways permit the placement of trashcans, to use as service lanes for delivery and for someone to run a business away from prying eyes.

These gaps keep humanity going. Gaps are opportunities for new beginnings. Their imperfect alignments open up a space for actions and invitations for renewal. In the Chinese language, the word gap consists of the character 间, which also refers to time or interval. 间 itself consists of 2 ideograms- a sun within a door, which one can interpret as a door left slightly ajar (a gap) that permits a ray of light to stream into the interior. At times, these intervals can become opaque. They prevent us from remembering. They cloud our past. They make us lose our identity, our memory. They keep commonalities apart and differences irreconcilable. These impenetrable gaps come filled. We don’t need a shim or caulking. In fact, we need to do the opposite- to crave away in order to remember again, to see the light, to connect and to reach out. The late New York Times journalist David Carr used the term Present Future to describe the state of journalism in the 21st century, where the present proliferation of news feeds that cater to a multitude of readers do not necessarily lead to a definitive, clear idea of what journalism will become in the future. Nonetheless, the future is slowly being shaped by these current developments and one should not shy away from them or be overly nostalgic with the past. Perhaps one can say the same for the future of design education and the practice of design? It is often convenient and easy to project a future scenario that celebrates technology (usually) and how it will herald a radical shift in the conceptualization, design, making and habitation of architectural spaces. However, we are also living in the present while making these projections; going through the daily, mundane but necessary rituals that sustain our everyday life. The body we carry with us still retains the memories of thousands of years of evolution despite continuing tempering by new technologies. Cultural background too, influences one's disposition towards new ideas and discoveries, which affect how fast the future becomes the present. Retaining the present with the future is therefore a wise and prudent step in our curiosity to uncover what lies beyond the horizon.

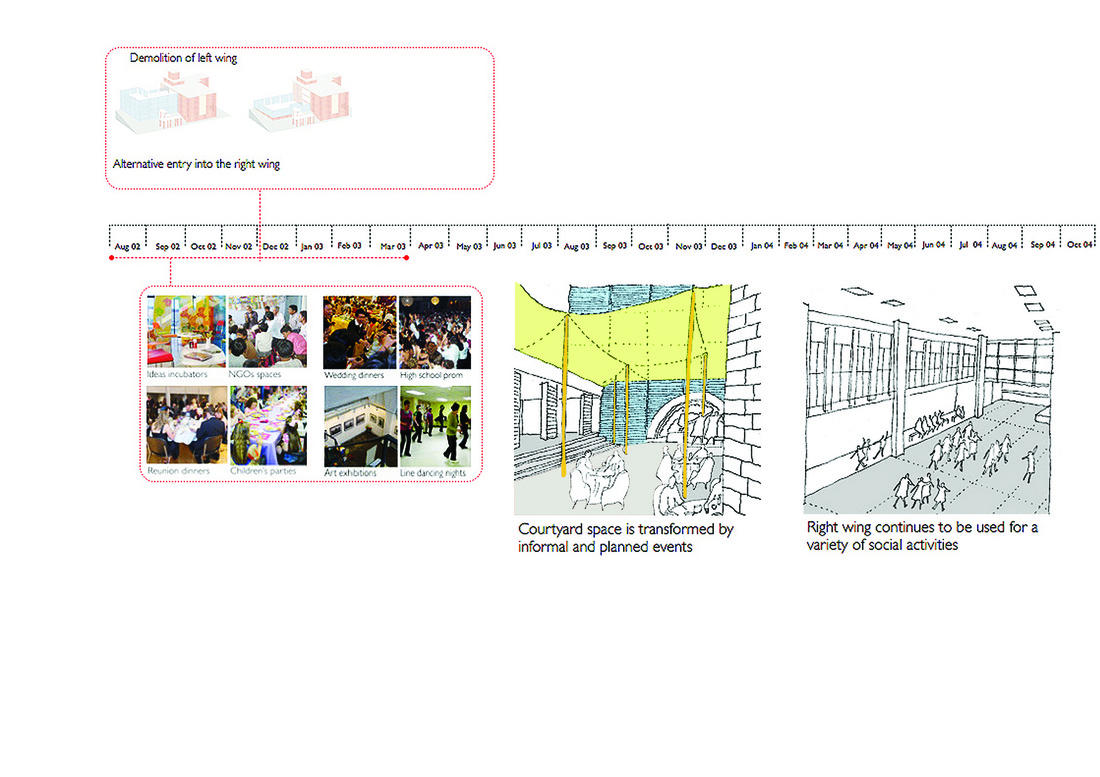

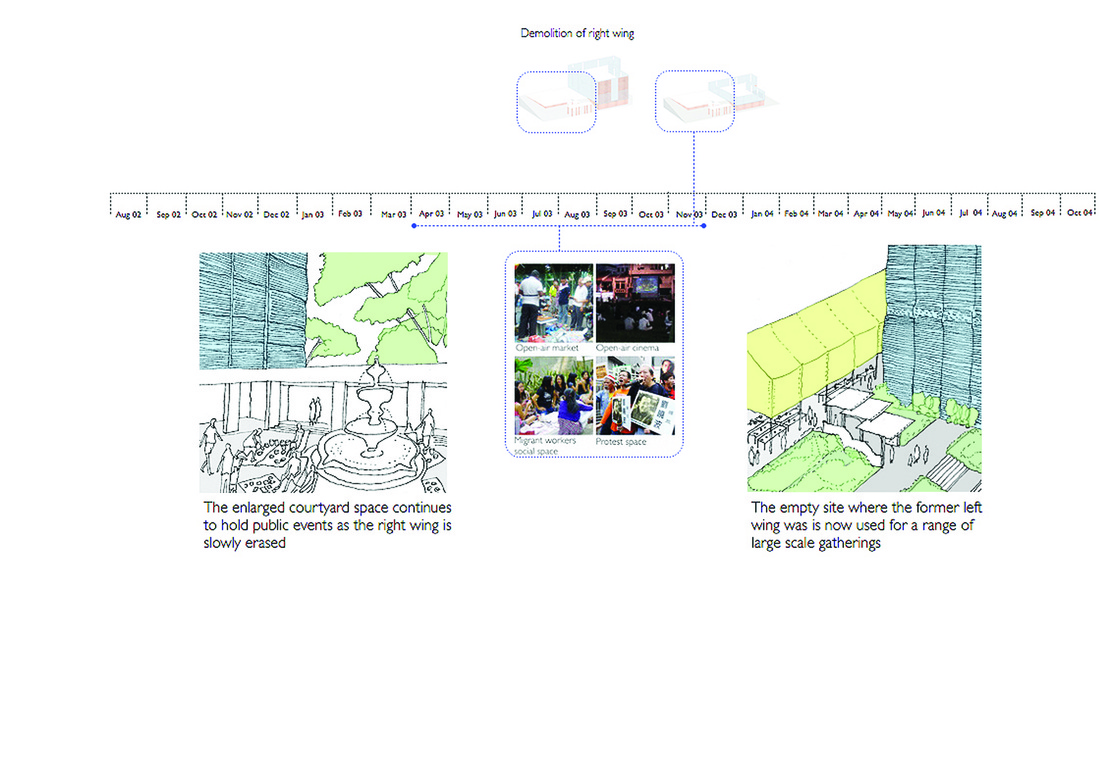

The project seized the opportunity to provide the public a chance to be involved in the active remembrance of this much loved building through a process of dynamic re-programming and unbuilding over a period of two years. The library was a long established institution in the country and slated for demolition in order to make way for an underground expressway despite several public pleas for its preservation. Instead of closing the library and leaving it vacant till the demolition date, a series of events and uses of this building were proposed, according to their scales and temporal natures within the 2-year period. The notion of preservation and collective memory in the city took on a different meaning, while the idea of providing a slow passing of this building was akin to how we hold a period of remembrance when a loved one or friend passed away.

A lot has been published and spoken about creativity and innovation, with business schools jumping onto the bandwagon proclaiming design thinking as the big savior that will bring about innovation in the business world. Some even claim they teach design, and travel the world peddling their one-liners and design workshops. It is good, on the one hand, that the popularization of design has given the field a wider audience and expanded the scope of design services. However, it has also greatly undermined the deeper value of a good design education. Therefore, Robert Grudin’s book, The Grace of Great Things is a breath of fresh air for me as an educator and a lifelong student of architecture and design. Grudin situates creativity and innovation within a larger social context that demands the persistent renewal and questioning of self and the world. To be creative requires the development of character, and enduring human values of imagination, integrity, courage and surprisingly, the value of pain as well. Pain in the creative process, which he identified four types; perception, expression, closure and self-expression, is vital if one were to overcome psychological barriers of stepping into the unknown, of persisting, completing and accepting criticism. For Grudin, modern society’s desire to remove pain, to avoid unpleasant moments, to be overly accommodating and to have excuses for failure to the point of blaming the system has developed into what he termed as a ‘rhetoric of failure’. Project Mission

The Art and Design School Project is an interdisciplinary and creative project that offers a free, intimate and intellectual experience within a gallery setting for the discourse on art, design and contemporary culture. It is motivated by the tradition of experimental pedagogies and seeks alternative grounds for engaging the community of learners through non-conventional means of teaching and learning. Project Rational and Goals The Art and Design School Project is conceived first and foremost as a project. It exists as a liminal presence within a real space and is engaged with live participants but is fictive at the same time. This strategy supports the realization of the project’s goals while giving it the space to be experimental and critical. It challenges conventional structure and organization of a school, the methods of knowledge delivery and exchange, as well as the roles of learner and teacher. The project is strongly motivated by the possibility of opening up new concepts and strategies for the future teaching and learning of art and design. The Art and Design School Project therefore:

Project Organization The themes for the class will be crowd sourced and curated from the art and design community prior to the start of the project. A collective of artists, designers and scholars who have devoted considerable time to their work and who share a passion for this open, interdisciplinary form of knowledge exchange will be invited to facilitate the weekly thematic discussions. Practitioners and recent graduates in their respective creative fields are eligible to apply as student participants. They are selected from an open call for application and successful applicants are invited to join the Art and Design School for a 12-week session. At the end of the session, the students present their works, research or findings to an invited panel of experts in the art and design fields. Project Duration All the participants will meet once a week for 2 hours in the evening at a gallery. The project will take 12 weeks to complete. |

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed