|

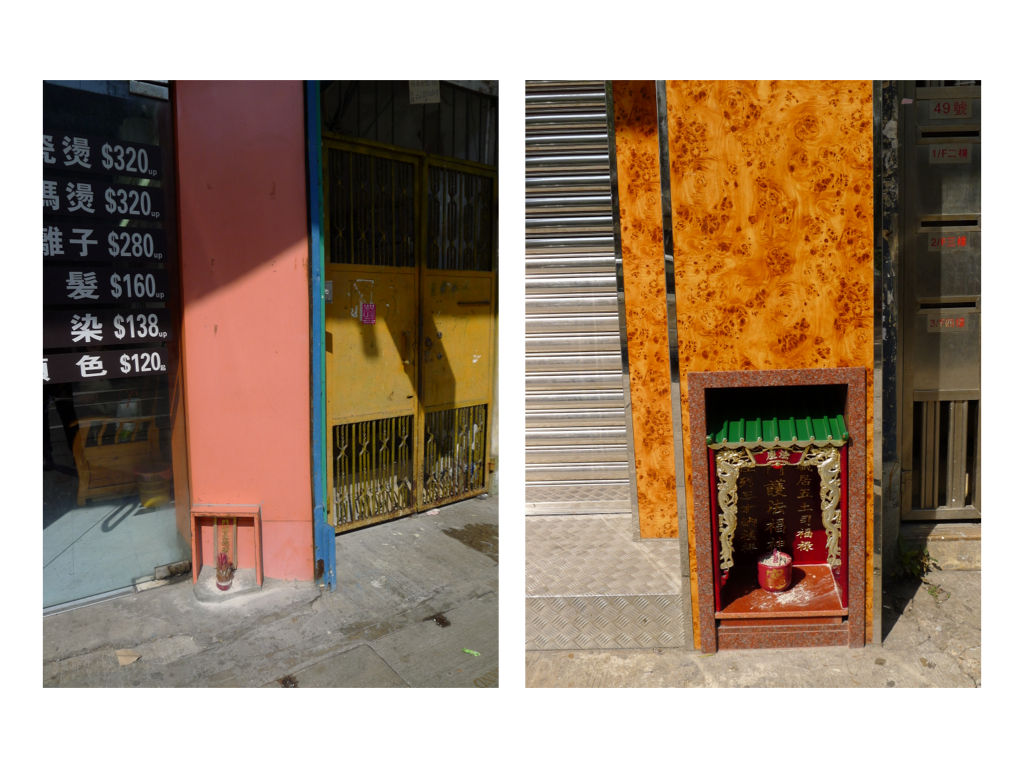

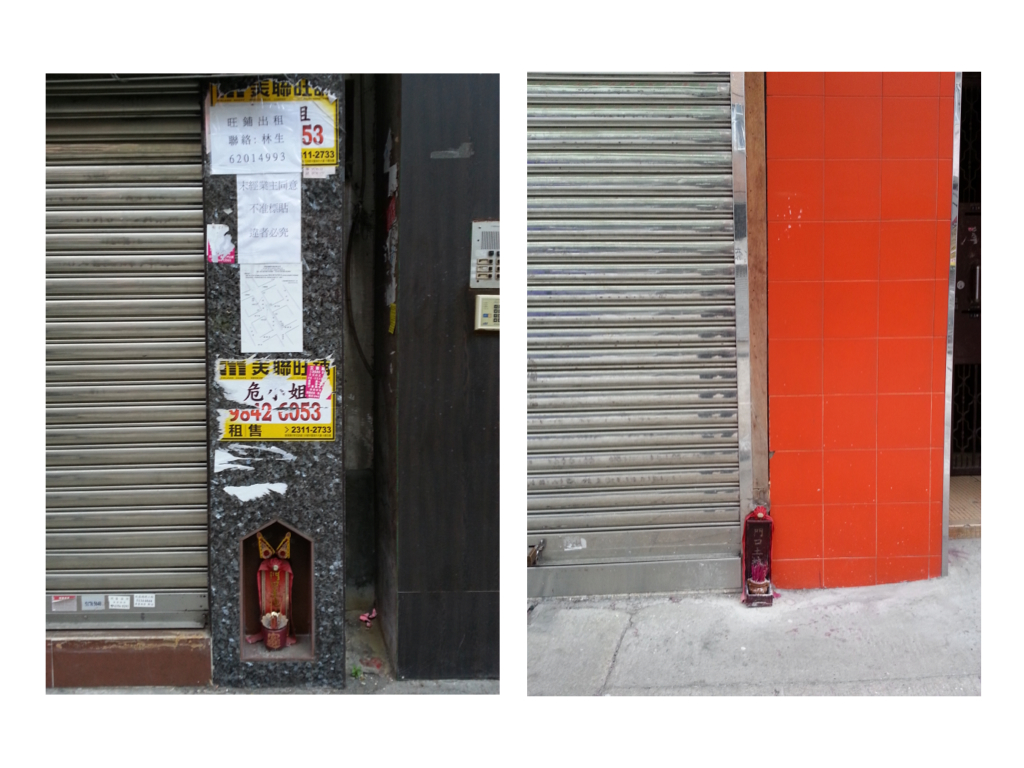

When walking around Hong Kong, one can still find the presence of the 地主神 or Landlord Spirit altar at the lower corner of many shop fronts. The 地主神 is there to bring business and good fortune to the shop owner. Although the original 地主神 altar has two lines of inscriptions that declare the protection of the owner’s wellbeing and to bring more businesses, recent ones are simply reduced to a single line that says門口土地 財神 or Fortune Earth God At The Front Of The Door. Some 地主神are well kept and there are special niches designed to house the altars. There are others that are simply placed in front of the shop corners. A few 地主神 were seen sharing the altar space with a neighboring 地主神, with the Sky God or are squeezed among other objects outside the shop. And there are those that needed a bit of cleaning while a few have fled the shop front when the shop owner relocated to another place or the shop closed down due to poor business. Perhaps the ability of the 地主神 to bring new businesses varies or because the shop owner did not take good care of the altar. Either way, the empty niche and the remnants of what used to be the abode of the 地主神 conveys a poignant picture. Professor Siu sent me this wonderful picture of an informal shrine set up by the protesters. He wrote, "The Guan Gong statue was worshiped by both the Police and the Triad Societies… And the citizens used this to counter their power against the protesters.

The story of the Wa Fu community space began almost 30 years ago. The place was a destination for residents living in the near by housing estate to leave their statues of porcelain deities when they relocated or when the religion was no longer practiced by the younger generation after the passing of the elderly family member. The stepped profile of the ground leading to the sea is an ideal site to place the deities. They are secured individually by a layer of cement to prevent them from toppling over during a typhoon. Through time, a sea of porcelain deities slowly emerges and are they cared for by a group of elderly residents. Some deities are protected by simple shelters while others share their spaces with toy figurines that were also left here. A self-constructed shelter serves as both a community space for the elderly and for them to keep their belongings. A well close-by provides fresh water for cleaning after taking a dip in the sea. We were told it is a popular activity among the elderly and younger residents. Some come for a swim early in the morning before heading off to work.

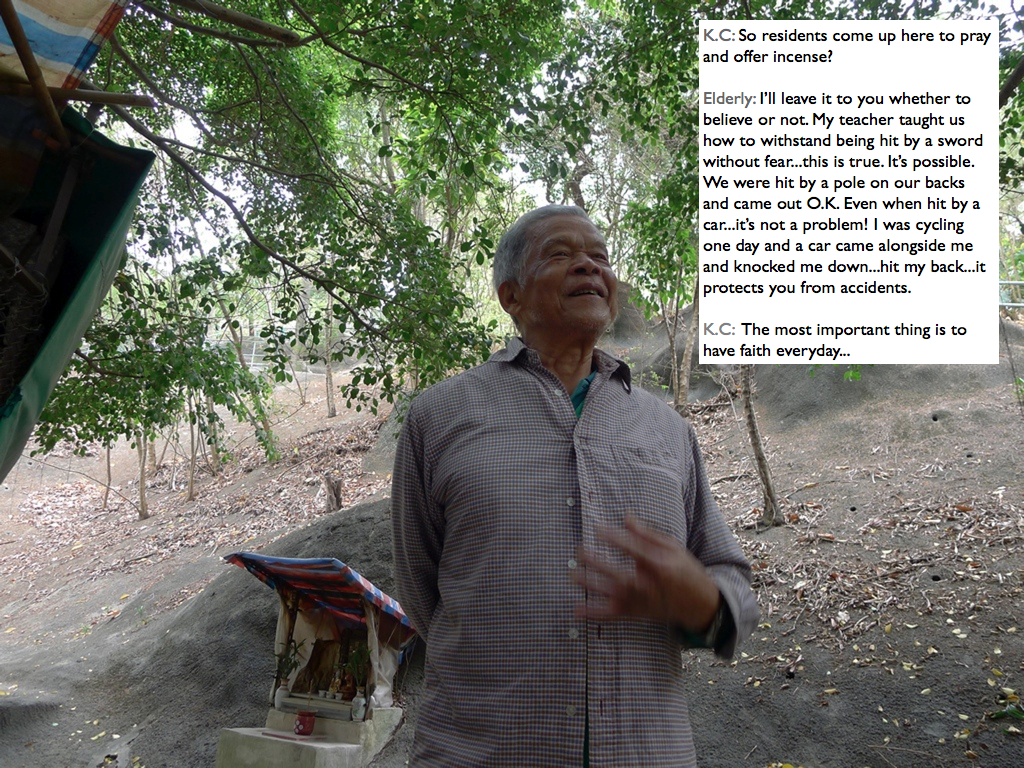

The hillside informal shrine in So Uk Estate is connected to a larger network of elderly walkers and informal social spaces. The shrine is situated along a path that winds up the hillside, which is a favorite spot for the mostly elderly residents and housewives to engage in their morning walks and exercises. The shrine is often a stop over for the residents. They would offer incense or a simple prayer at the shrine on their way up or down the hill during their morning exercise routines. Besides exercising, the residents have also undertaken small, self-initiated actions along the various exercising spots; such as plant caring, building of small concrete steps to link disconnected parts of the hillside and allow a safer walk up the hill, introducing resting spots, setting up support facilities for the morning exercises, and repairing broken planters. Water for the plants is collected from the natural run-offs from the hill in small pails and buckets. The So Uk Estate shrine and the adjacent exercising spots are excellent examples of bottom-up initiatives in place-making. It makes a strong case for allowing urban dwellers to take control and have the opportunity to shape their immediate spaces in the city rather than top-down initiatives that often miss the point and cost much more than they should be.

An interesting feature of highly urbanised and Westernised Asian cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore is the occasional Chinese religious shrine lying next to a tree, in a discrete section of a public space or at a certain road junction. Some of them are erected by individuals or groups to express their gratitude for an answered prayer or to ensure a harmonious environment. Others begin when the altars of “house gods” or religious statues are “left behind”, because the previous owners have relocated to another home, or because the younger generation no longer observes the same religious practices after the passing of elder family members. To the older Chinese generation, religious statues formerly acquired for home collection and worship are not to be discarded disrespectfully. They are either given to another “caretaker” or are relocated to auspicious places, such as under a tree or beside a roadside rock.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed