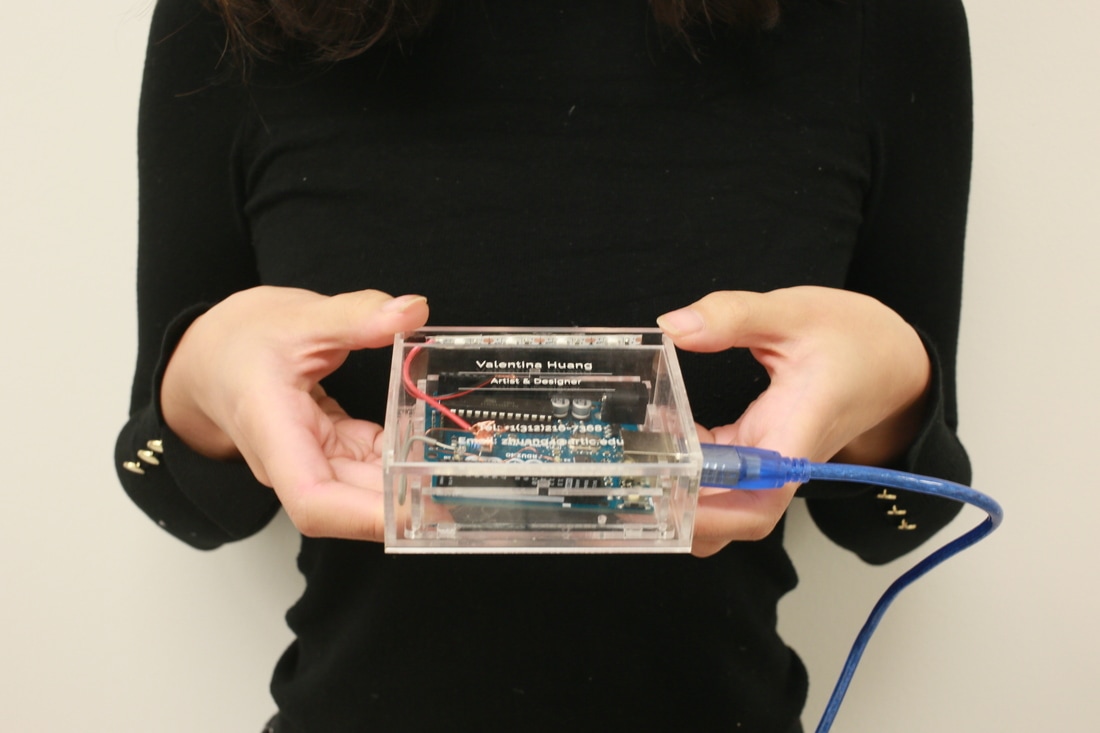

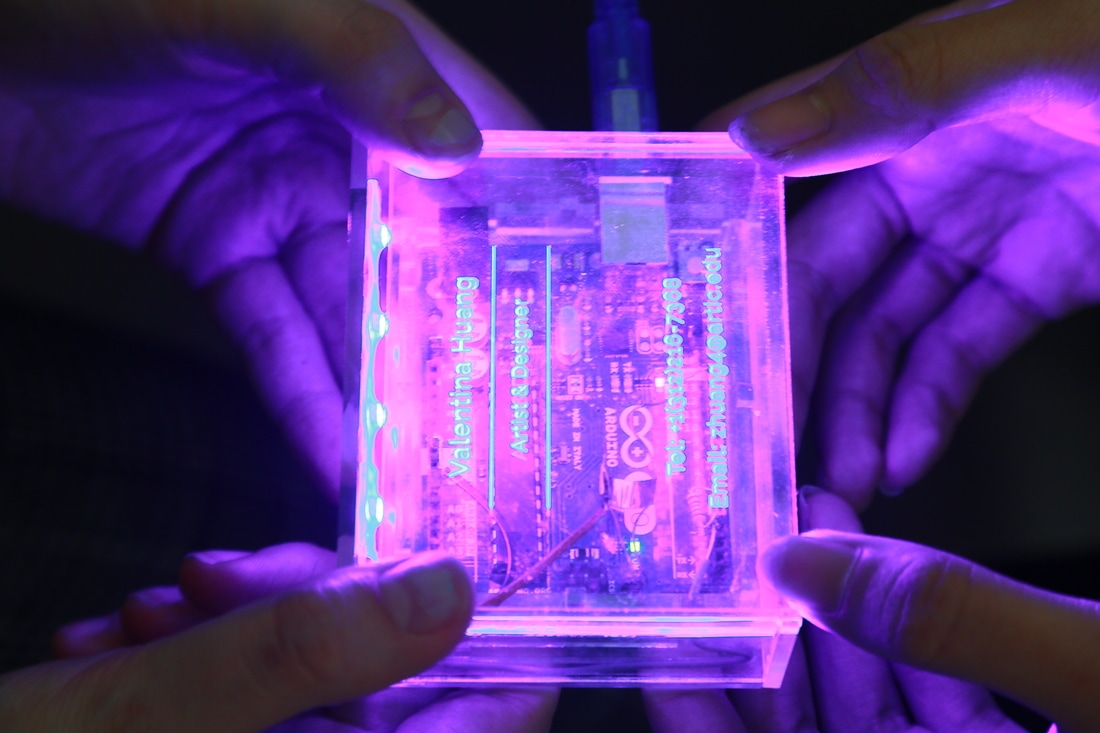

Valentina Huang’s experience of leaving her hometown and coming to Chicago for her graduate study informs her current works. Confronted by a different culture and language, Valentina’s first year becomes a continuous negotiation between her identity and her everyday life in the city. Using the business card as a formal introduction of one’s role and position in an organization, she designs a digital business card that lights up when touched by someone. As more people hold the card, the light intensifies and changes colors depending on the duration. In her second project, Valentina made a mirrored cube that she wears in public. The cube hides her face and reflects the surrounding environment. The cube allows her become ‘invisible’ and blend in.

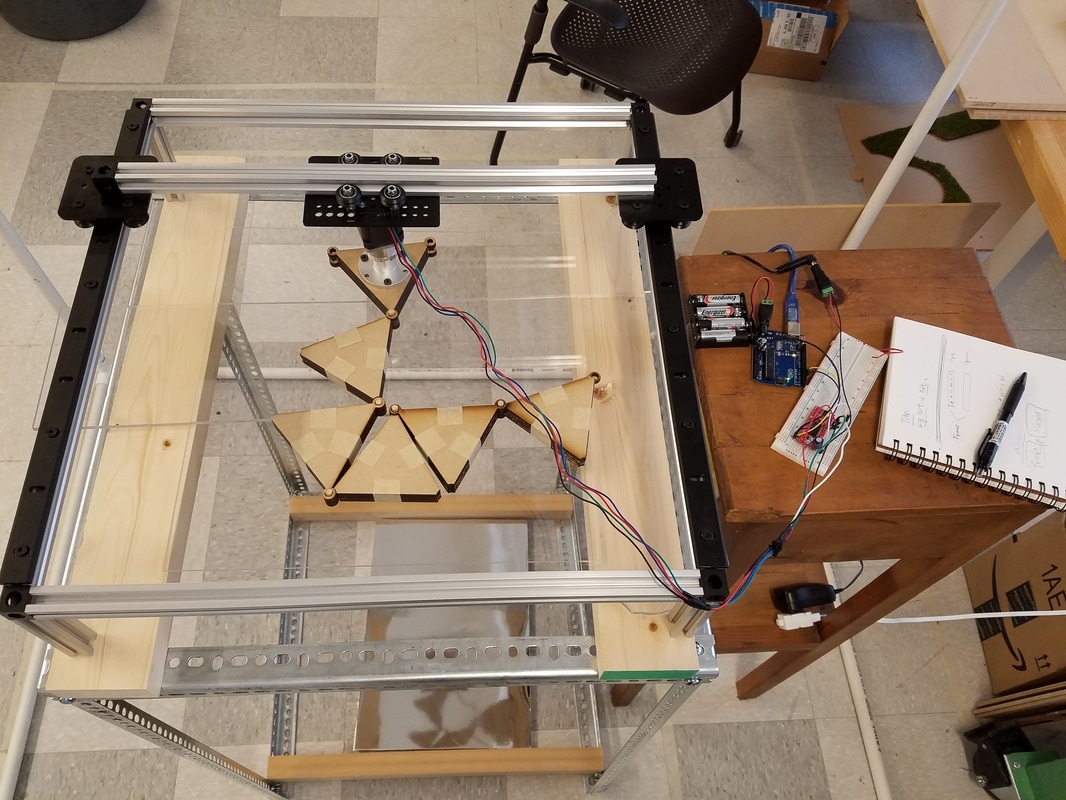

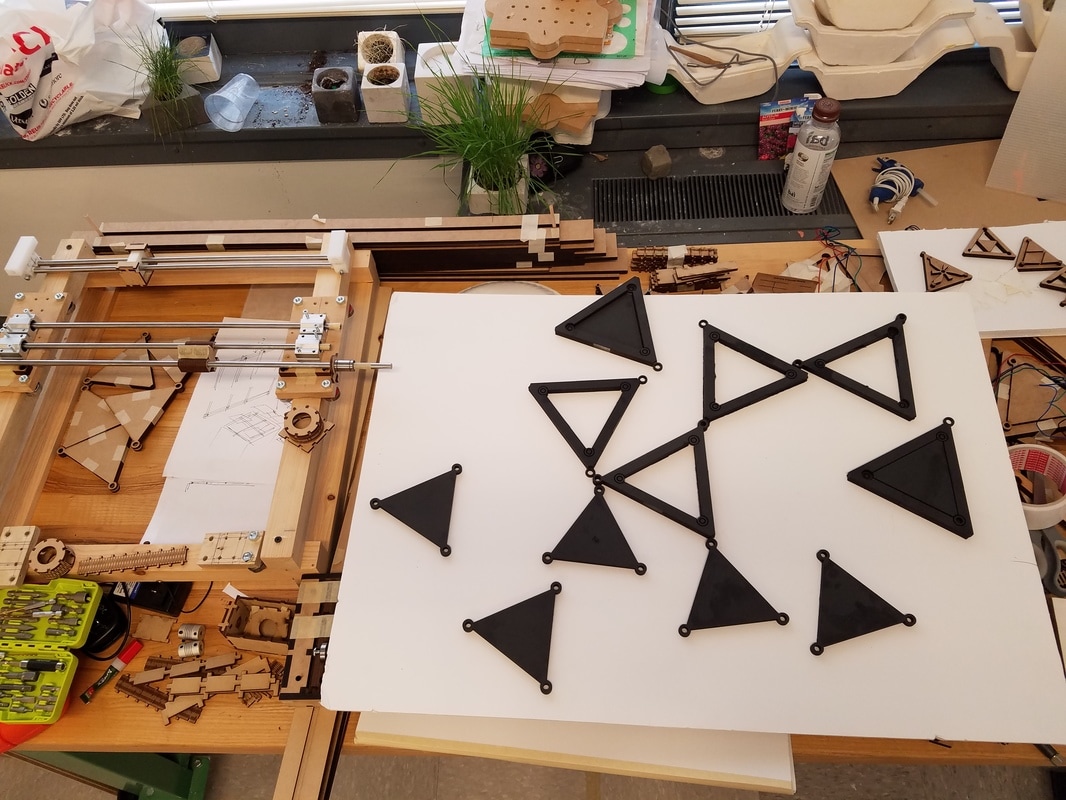

Kibeom uses machines to depict the dynamics of social relationships. His carefully constructed social interaction machine consists of a number of tessellated parts stringed together and powered by a centralized motor. Each can be fitted exactly or awkwardly depending on the nature of the movement. When formed into a whole, it alludes to the formation of a community momentarily, before it breaks up and takes on a different configuration. Its unpredictability echoes the nature of our human interactions. They can swing from a harmonious moment to one of tension. The silence of the motor and the quietness of the moving parts give off an uncanny feeling. They evoke a continuous stirring of our thoughts and emotions that even though invisible, can become evident as actions. On the other hand, the centralized motor questions whether human agency is truly independent and free.

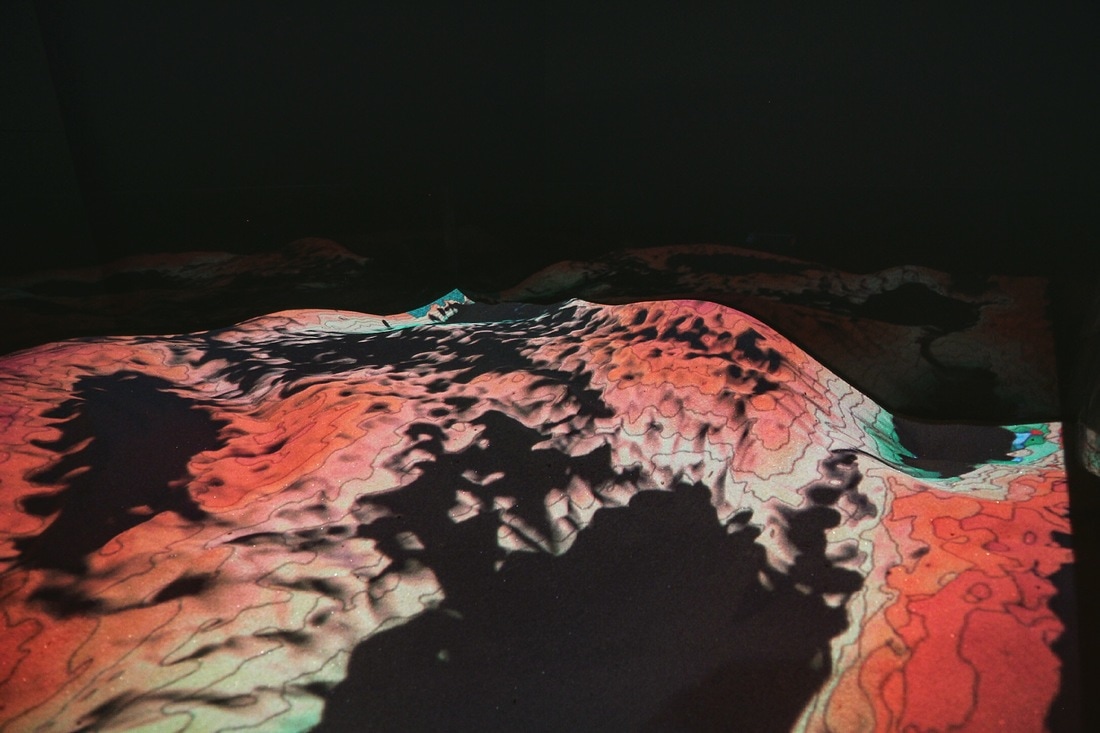

As a Native American with a background in architecture and currently a first year student in the MFA in Studio (Art and Technology), Lawrence Santiago X work is focused on how technology can play a critical role in the recovery of his people’s culture and social practice. He devoted his first year to the design of an immersive and participatory work that brings together indigenous symbols, belief systems and performance through the use of motion sensing and data visualization software. His latest work is a 6-minute performance that highlights the devastation of the earth and culminates in the complete submersion of the terrain by oil. The performance is accompanied by the digital projections of indigenous sacred mound images on the walls and ceiling that are choreographed to be in sync with a repetitive Native American chant music.

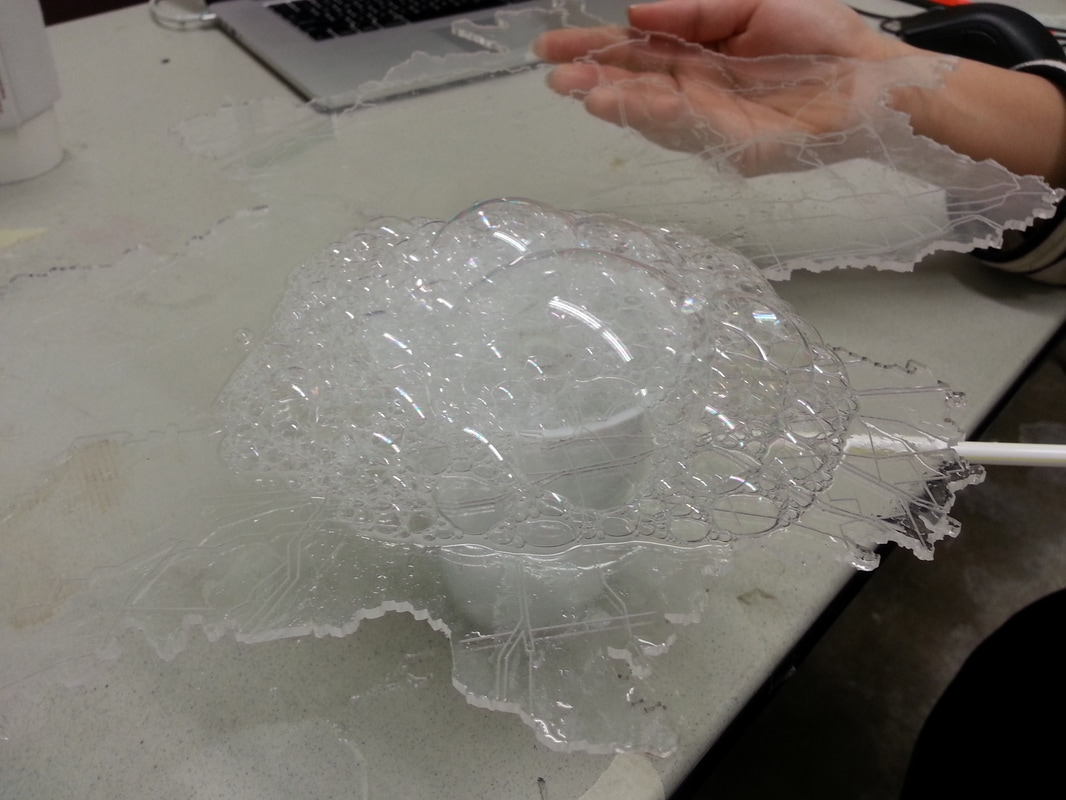

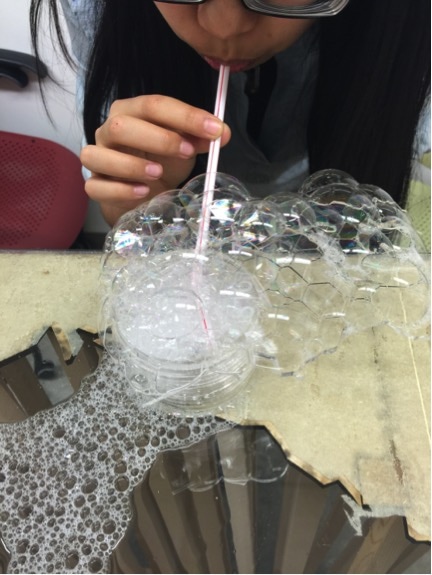

The work by MFA in Studio (Architecture) student Lu Jiacong revolves around several scales and topics- the ongoing pollution crisis in China, the ephemeral breath drawings by Chinese artist Song Dong and Bucky Fuller’s proposed dome over Manhattan in the 1960s.

Jiacong is fascinated by ambiguous boundaries; the shifting, unpredictable and potentially scale-less experience of space as a result of changing forms. Through our conversations, it was apparent that the clouds carrying pollutants drifting over China are also forms of shifting boundaries that have devastating consequences regardless of the pollution source. One is at the mercy of the wind direction whether the pollution level rises or falls. Jiacong recalled her early childhood in China where elementary school children were tested annually in the healthy lungs program. Each child dutifully lined up and took turns breathing into a machine that recorded the strength of each exhale. A number flashed on the screen to indicate the power of each student’s lungs. Interestingly, Chinese artist Song Dong created an art piece in Tiananmen Square by simply breathing onto the ground on a very cold winter night. Persistent acts of exhaling gradually created a thin, small and fragile layer of ice over the vast grounds of the square. Although the impetus of his work was not the pollution crisis in China, one could find parallel discourses around the ephemeral qualities of art, the use of the body and its biological function as a generator of art works and the tension between the space of the state and the individual.

For Jiacong, the use of foam bubbles came about after several experimentation with other soft, malleable materials. The process of forming by blowing into a straw also engendered an intimate relationship with the act of making, not unlike how Song Dong made his art in Tiananmen Square. Moreover, it echoed the healthy lung-testing experience of Jiacong’s childhood. Instead of a number at the end of each test, a series of foam bubbles were formed on the surface. It is conceived that several participants could play together to create a family of bubbles covering the territory. Depending on the level of cooperation, each team or a singular person, if he or she had great determination, could create a protective shelter over the city, albeit at a model scale. Could this simple act of playing and shaping an ephemeral form be a rallying and energizing point for the residents to work together and confront the larger nation-wide pollution crisis? Design is often seen as a material based endeavor. Here, shaping the consciousness of the residents towards a collective action through play is equally vital. When Bucky Fuller imagined a mile high dome covering a diameter of 1.8 miles over Manhattan, it seemed a preposterous idea at that moment in time. It was visionary to say the least but it remained the vision of a singular man. More than 50 years later, perhaps it could become a timely solution to the current environmental crisis in China. Not in the grand, heroic fashion of Bucky but as a series of gentler, more distributed, multi-scalar and co-created bubbles protecting the residents and sustained by them in some of the most polluted Chinese cities.