|

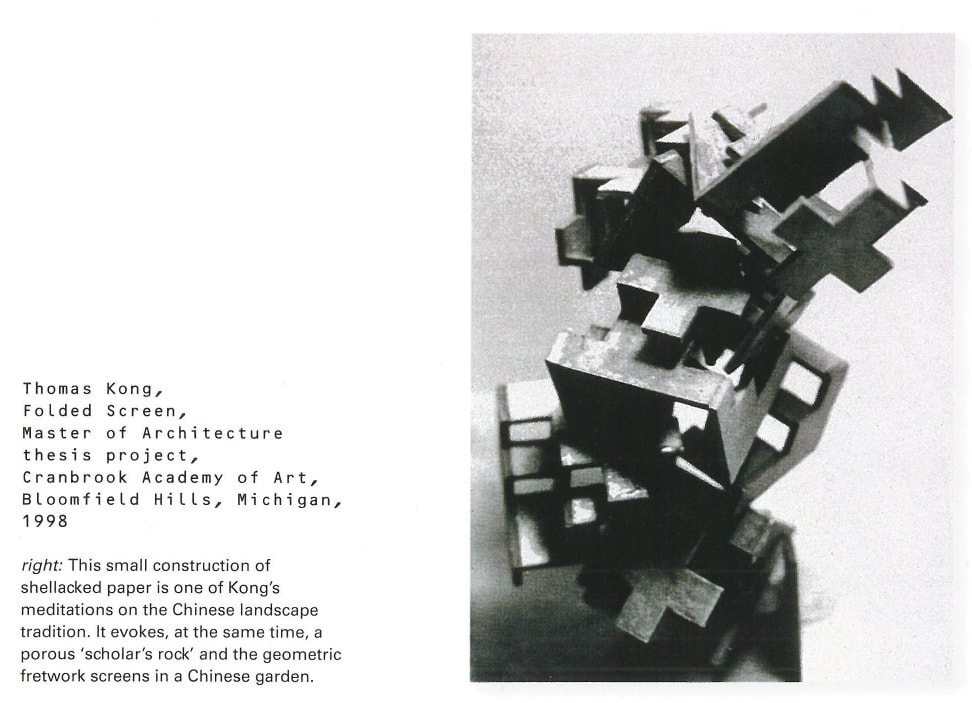

I am honoured to have my work featured by Cranbrook Academy of Art Artist-in-Residence Peter Lynch in the recent issue of Architecture Design.

Architecture is a technical solution to problems that are not technical at all. Mark Wigley.

In his lecture in Chicago, the Brazilian architect and 2006 Pritzker Architecture prize winner, Paulo Mendes da Rocha said,

‘The problems of architecture are fundamentally philosophical.’ His words brought back memories when I was an architecture student pondering over the difference between architecture and building. I could not find an equivalent of the word architecture in my native language and this question has remained in me ever since. Looking back, my teaching, research and practice were elliptical efforts to clarify this question and my continuing quest for reconciliation. Having practiced as an architect for sixteen years, I have come to believe that architecture carries something beyond the act of building. Architecture offers a surplus, a generosity that the performative aspect of a building lacks. Whether one calls that surplus beauty, grace, poetics or social agency, it is a pursuit of significance. Architecture can exists both within and outside of building; as a form of discourse, a thought-experiment or a strategy that reveals the potentialities of things and their relationships. It can simultaneously be an affirmation and a denial of building. Its paradoxical, ill-defined and permeable existence is at once liberating, marvellous and unsettling. The Art and Design School Project is an interdisciplinary and creative project that offers a free, intimate and intellectual experience within a gallery setting for the discourse on art, design and contemporary culture. It is motivated by the tradition of experimental pedagogies and seeks alternative grounds and ideas in engaging the community of learners through non-conventional means of teaching and learning in Singapore.

Project Rational and Goals The Art and Design School Project is conceived first and foremost as a project. Its liminal presence, by situating within a real space and engaging with live participants yet fictive and future-oriented to some extent supports its unfolding in a projective but pointed and systematic manner. It challenges conventional structure and organization of a school, the methods of knowledge delivery and exchange, as well as the roles of learner and teacher. The project is strongly motivated by the possibility of opening up new concepts and strategies for the future teaching and learning of art and design in Singapore. The Art and Design School Project therefore:

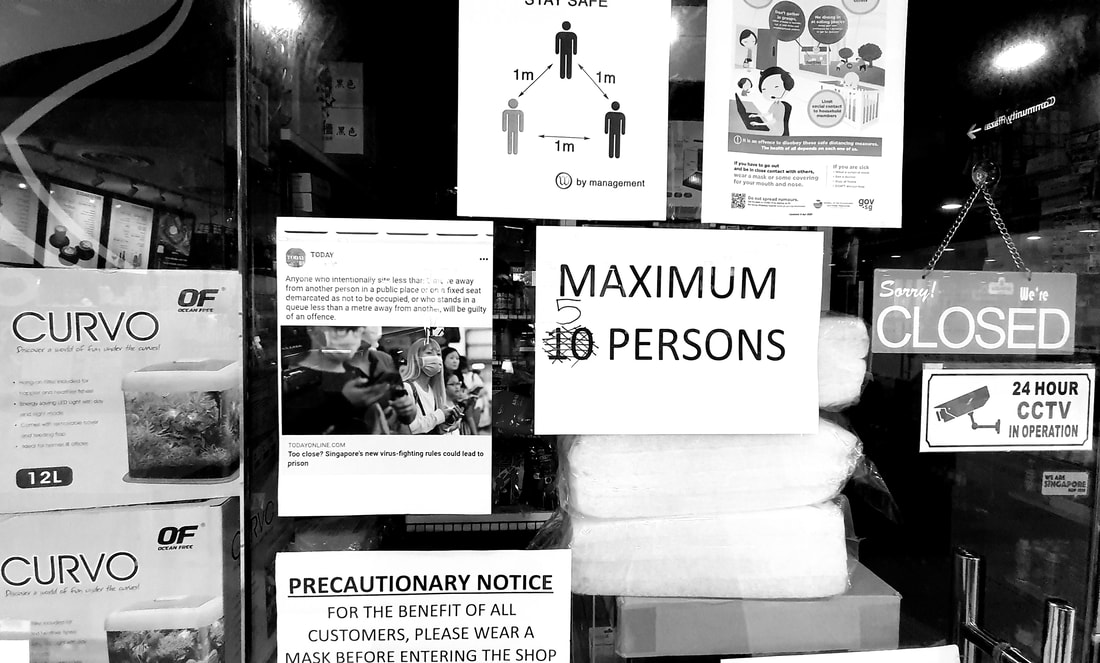

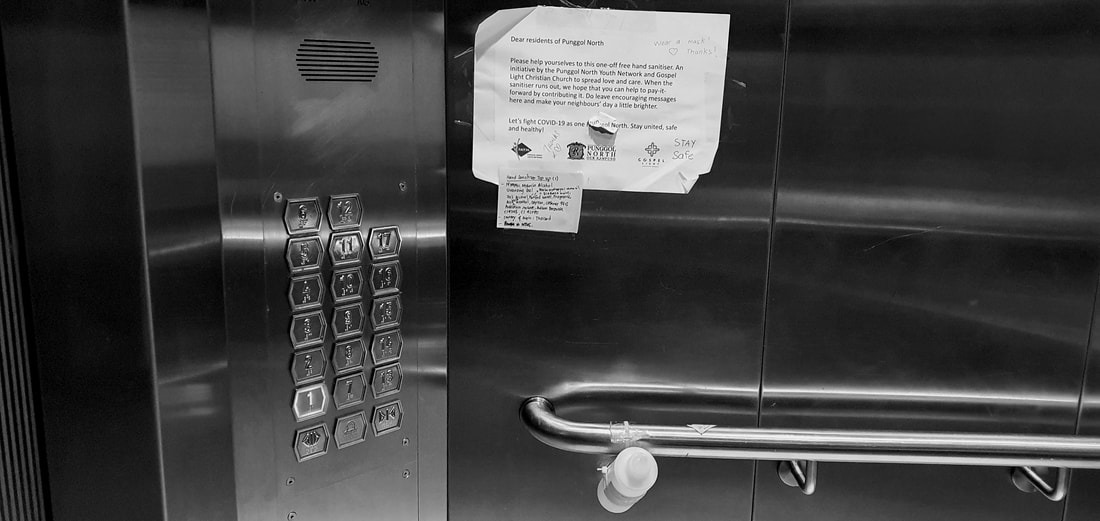

Taking Singapore as a laboratory for the thinking and design of future healthcare spaces, services, and deliveries, architecture, and industrial design students worked together to develop innovative and scalable solutions for a distributed healthcare system in the year 2030. The projects are collaborative, multi-scalar, and multi-stakeholder in approach. They considered near-to-far-future scenarios for a distributed system across different sites, touchpoints, and experiences by harnessing digital technologies, deploying connected care platforms, and being supported by grassroots organizations, social agencies, and communities. Healthcare 2030 was led by architects, experience, and industrial designers who aimed to provide an interdisciplinary, collaborative, and empathetic studio experience.

View the virtual exhibition: https://chio.space/virtual-tour/healthcare-2030/home The Covid-19 pandemic has challenged and uprooted our lives in ways unimaginable on a global scale. When cities are locked down for an extended period and their inhabitants told to stay home, these unprecedented social restrictions are counter to our fundamental way of life. For personal safety and social responsibility reasons, careful considerations now intercede simple, everyday interactions that we take for granted before the pandemic.

Architecture has emerged in the public's consciousness in recent years, with architects portrayed by the media as cultural shapers and movers in society. American architect Elizabeth Diller, partner of New York practice Diller+Scofidio Renfro was listed as one of Times magazine's 100 most influential personalities of 2018 while the globe-trotting Danish architect Bjarke Ingels is regularly featured on CNN expounding his design ideas and projects. On the other hand, cities are hastily organizing architecture biennials and triennials with the hope of projecting their cultural capital to an international audience. There are a total of 34 biennials and triennials globally, with 22 being hosted in different cities concurrently the same year. The Venice Biennial, the oldest and most renowned among the biennials saw over 60,000 visitors in just the first three weeks alone in 2016. The final total number of visitors was 260,000, which was a record for the biennial. Politicians, policymakers and brand consultants are quick to seize on the promotion of culture in enhancing liveability, to attract global talent, tourists and increase economic competitiveness, It is a narrow yet alluring definition of culture that is perceived to boost a city's spot in the annual global city ranking exercise. This is not surprising. As cultural artifacts, buildings carry strong cultural currents in our built environment. They reflect the values, beliefs, and customs of a society at a particular point in time.

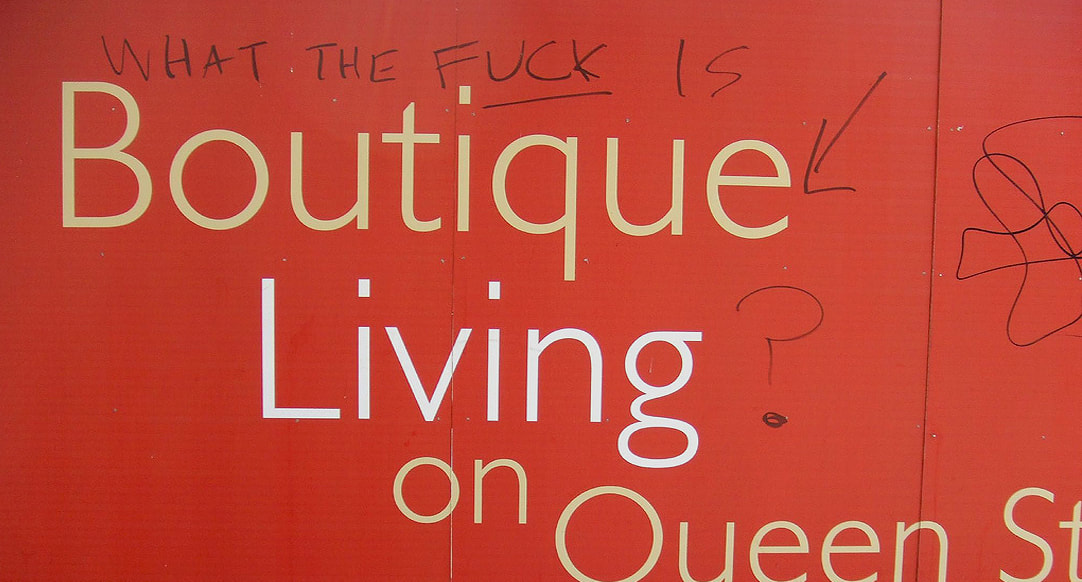

The word culture has its origin from the Latin word cultura, which means 'to grow,' to 'cultivate.' In Biology, culture refers to the growth of bacteria and cells by providing the right mix of nutrients and conditions. Whether it is the growth of bacteria in a petri dish or the cultivation of culture in society, time, patience, care, commitment, attention, and nourishment are needed to allow something to come into existence. It is an emplaced process, bounded loosely in a locale or within the glass confines of a petri dish. In his 1958 essay, Culture is Ordinary, Raymond Williams bemoaned the association of culture only with the high culture of the arts like literature, painting, dance, and theatre. To be cultured means having a taste for the finer things as opposed to a low culture, which belongs to the masses. Williams argued that both high and low cultures coexist in our lives, and we should instead be looking at culture as a 'whole way of life.' In other words, our everyday existence, in which we engage in myriad forms of daily activities, interact with people from different walks of life and in spaces that are both ordinary and exquisite. Although written in 1958, it still serves an important reminder to architects and architecture students. As spatial designers who can influence behaviors and actions, and modulate perceptions through our design, we, too, must be mindful of the manifold and sometimes competing cultures commingling amongst us. It is especially critical at a time when increasing socio-economic inequality frustrates, excludes and divides society, and the rising voices of underrepresented communities who demand to be heard. First. A true story- The director of a global, multidisciplinary design firm based in London was asked, "What do you look for in a new employee?". His reply, "Perhaps a sense of humor?"

Graduating students take note. His reply seems flippant and perhaps irresponsible. Having taught at SAIC, a private art and design school for over 12 years, that was certainly my first reaction. Out of curiosity, I Googled "Why a sense of humor is important?" and found 288 direct links out of 113,000,000 results (in 0.45 seconds). The positive impact of humor on personal relationships, emotional wellbeing, in the workplace, and in businesses is astonishing and offers a moment of reflection for me. It parallels the debate between the two central characters over laughter in the novel "The Name of the Rose," by Umberto Eco. Set in the Middle Ages, William of Baskerville, a Franciscan monk argues for careful deliberation and interpretation while Jorge de Burgos, the elderly and blind monk from the abbey harbors deep suspicions about laughter. To him, laughter is diabolical, subversive. It reduces the serious learning of the monks to triviality and farce. Laughter destabilizes and erodes the status quo. Jorge de Burgos, therefore, sees it as his sacred duty, to the point of committing murders and burning the library (apologies for the spoiler) to protect the established, divine order before it descends into anarchy. We are witnessing a profound shift at all levels of society that will significantly impact lives on the planet, and a new order is taking shape. Received notions of identity, belonging, ownership, access, and control are questioned and subjected to a re-examination in our current social, political and technological milieu. Architecture as built culture is not immune to scrutiny. The thesis projects of the Class of 2019 bear testament to such scrutiny. The students know where they stand in the debate between William of Baskerville and Jorge de Burgos. They are not cowed by fear or anxiety, nor are they resigned to the present state of affairs. Their projects offer a glimpse of certain possibilities at a time of transition and uncertainty; personal declarations forged and materialized over two semesters of conversation, debate, research, drawing, testing, and making. They invite us to share their defiance, hope, ambition, curiosity, imagination, and resilience. I would add a sense of humor to the mix. Unlike the misplaced aversion to laughter by the zealot Jorge de Burgos, it is an invaluable tool that builds conviviality, breaks down tribal instincts, crushes the climate of fear, disarms a tense situation and bridges differences. Or as the irrepressible John Cleese, one of the founding members of the Monty Python comedy group once said, "Laughter is the force of democracy." May the graduating 2019 class of the Master of Architecture and the Master of Architecture (With an Emphasis in Interior Architecture) finds fulfillment, success, and brings forth joy and laughter through their work. Skill acquired through practice and prior experience forms knowledge and is context-dependent. The problem with a peripatetic pedagogy is the lack of a stable context to learn and hone a skill over time. Learning a skill is not following a set of instructions like in recipe book. It is not a direct, passive transmission, but a conjoined activity that requires the learner to develop a sensitive mind open to discovery and find congruity and meaning between the learner's personal experience and what is learned.

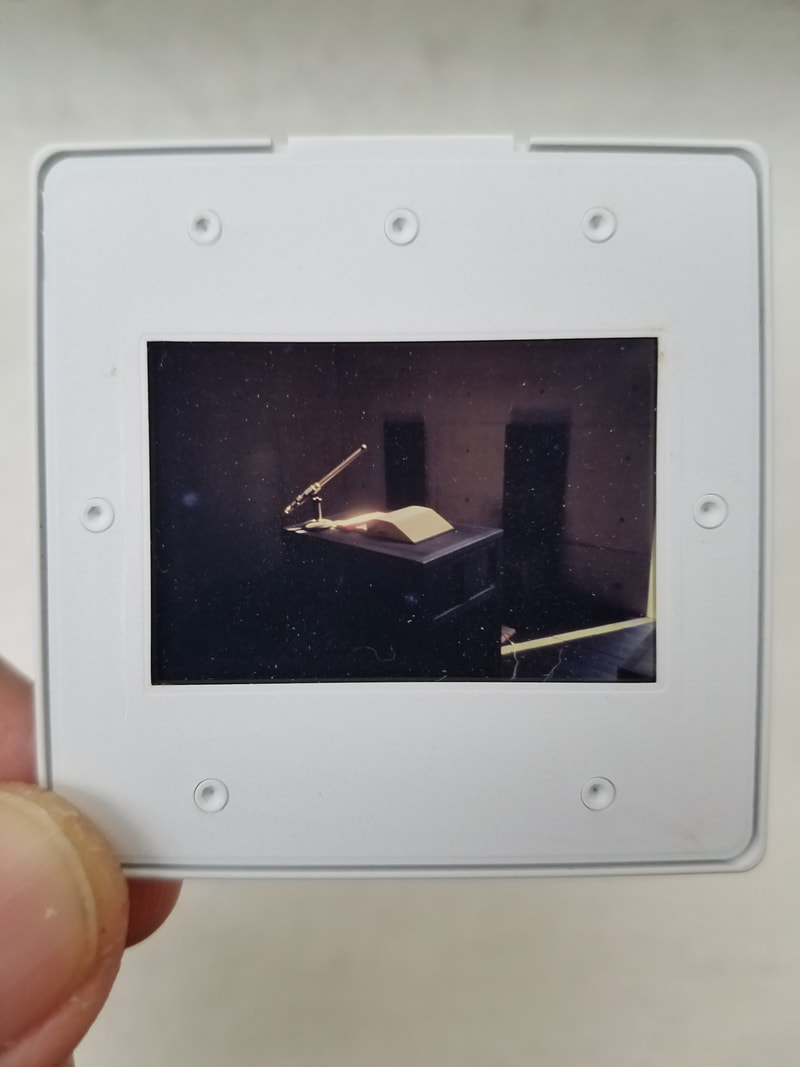

I visited Tadao Ando's Church of Light in Ibaraki, Japan, many years ago and found this slide as I was packing my library. I recall I was alone in the church and taking pictures of the interior and the furniture. When I turned around, I saw a beam of light streaming from the cross-shaped opening on the end wall. It went across the floor, up onto the pulpit, and over an opened bible.

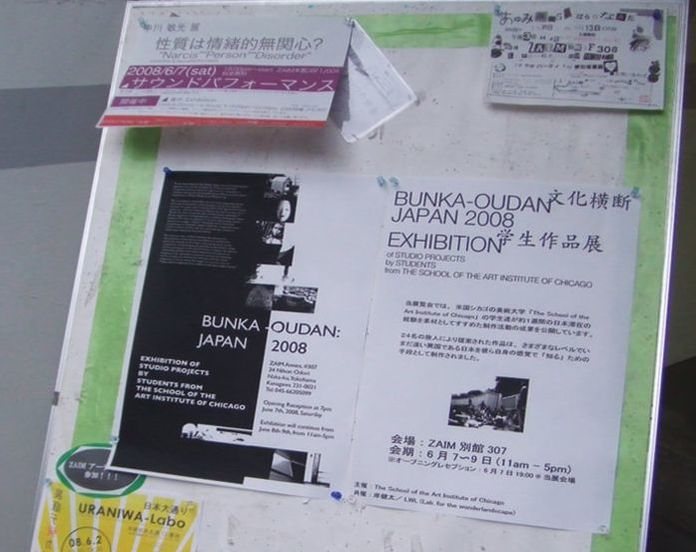

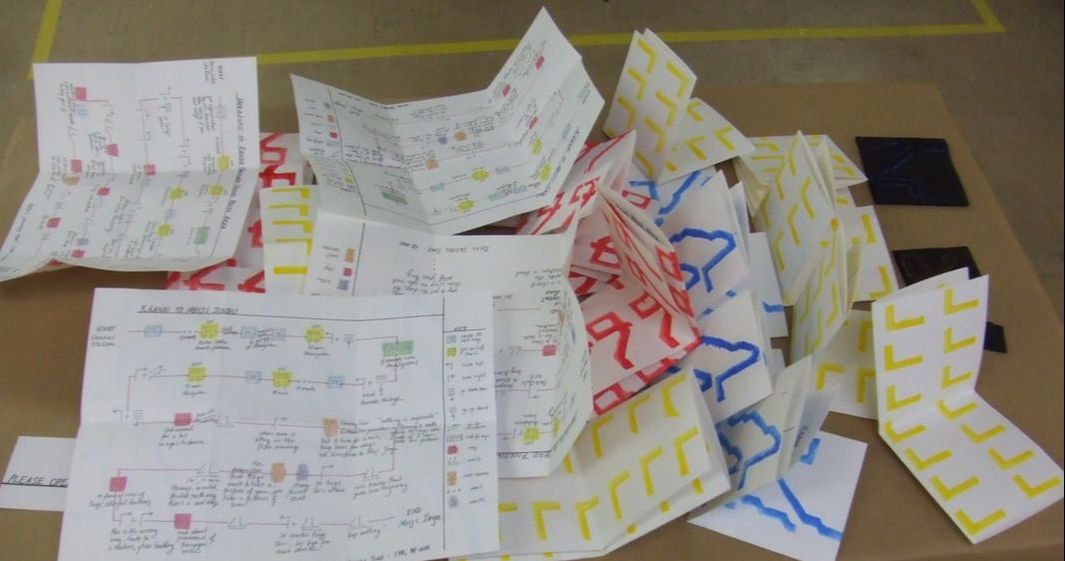

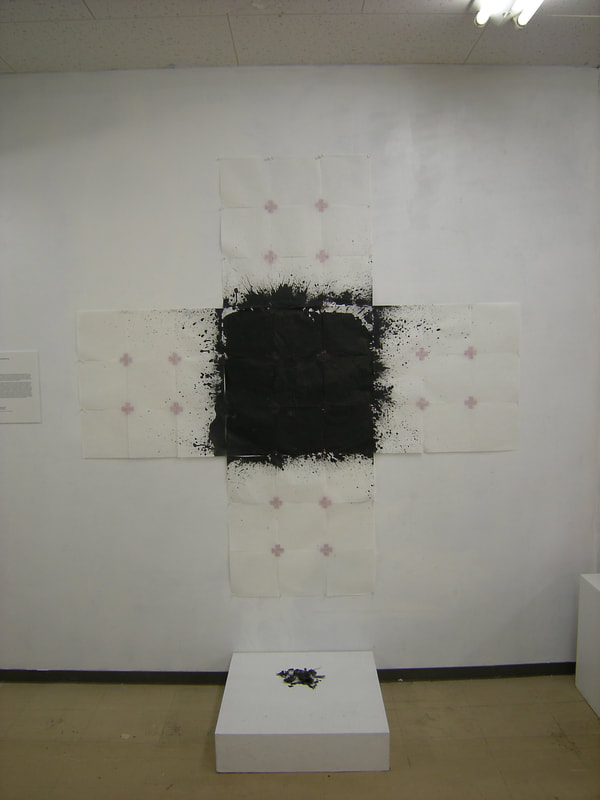

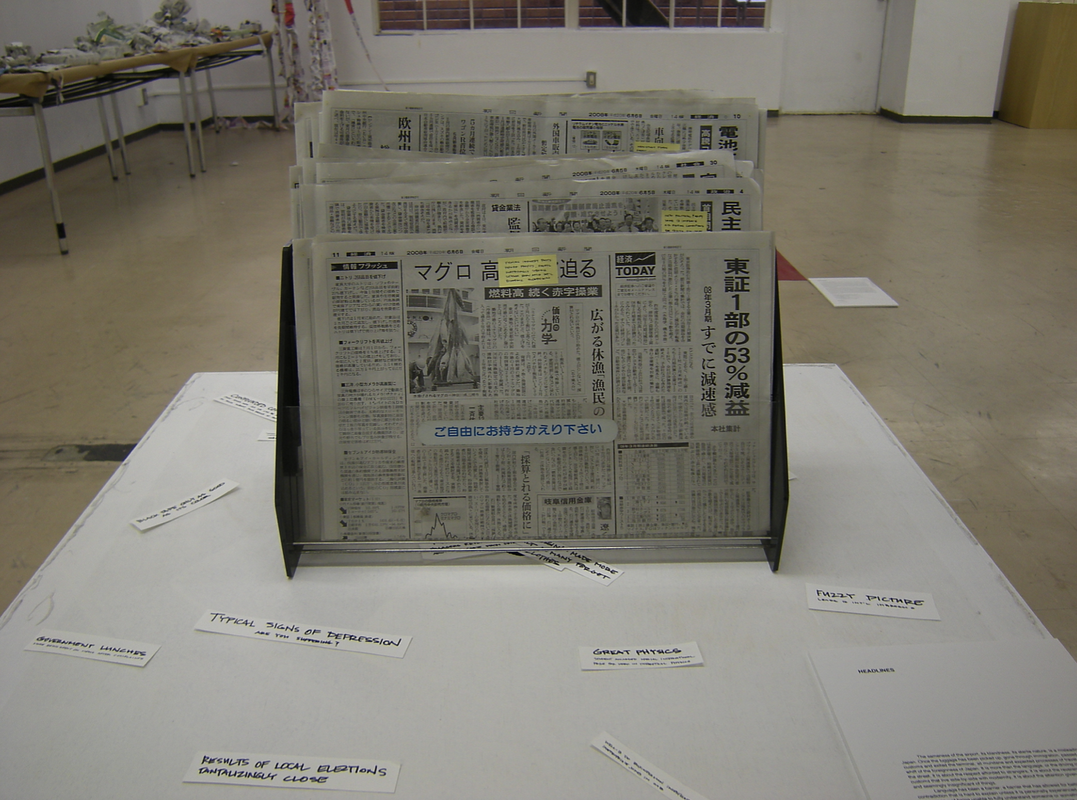

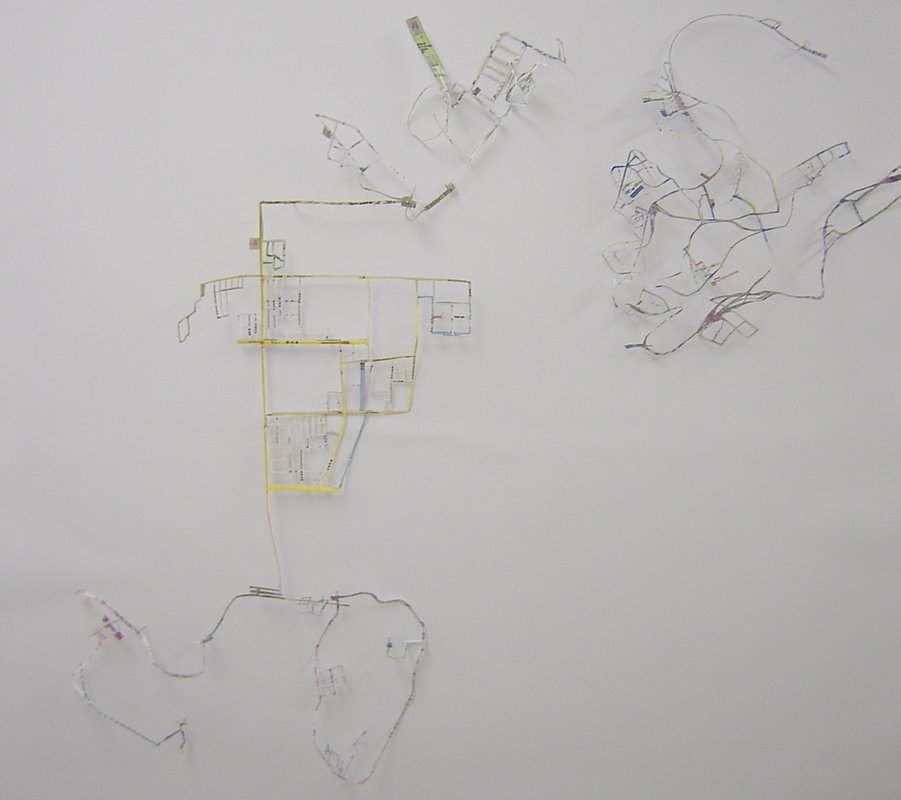

In his book The Empire of Signs, Roland Barthes offered one reality of Japanese society through his readings of an array of everyday objects, activities, places, body gestures and features as well as the arts. Edmund White, reviewing Barthes’s book in the New York Times Book Review wrote, “If Japan did not exist, Barthes would have had to invent it…” Similarly, in our everyday life we face a ubiquitous stream of stories, news, data and information disseminated through different media locally and globally. Whether we categorize them as facts, truths or rumors, their constellations around the globe continue to shape and reshape the reality we live in. As an architect, a designer and an artist, we are also shaping the world around us by amplifying, challenging and re-defining the given through different media and scales. The Bunka Oudan project begins with a few primary questions on Japan and will end with an exhibition of our personal maps. What is Japan? How do we know Japan? How do our preconceptions of Japan affect our on the ground experience? How do we depict our encounters and experiences in a map that is both personal and sharable? Thomas Kong. Associate Professor. AIADO Handkerchief Maps Almost from the moment I arrived in Japan, I have been fascinated by its train system, which is possibly one of the world’s most efficient and extensive, running the length of the country, from major metropolises to small villages. The station, at the center of this vast network, acts almost like a living, breathing organism, inhaling and exhaling people, filling up and emptying, every hour, every day. For the Japanese, these dense, frenzied transitions from station to station are a part of daily life, but as a tourist, unused to such intense, crowded movement, it made me very conscious of the way people negotiate and traverse space, and the signs that mark these processes. This kernel of a thought began to grow as I visited several Shinto shrines, most notably the Grand Shrine of Ise. In walking through a Shinto shrine, it is not just the main building that is the shrine, but the journey leading up to it – the experience of getting there is as important as the destination. If you speed up the ritual of the shrine, you arrive at the train station, at the city. In Tokyo, the heart of this vast intersecting system, once you emerge from the underground maze of platforms, shops, and human bodies, a different type of journey begins. Tokyo is a city without street names and numbers – you have to locate where you are and where you are going by other indicators – a storefront, a mailbox, a vending machine – or by asking people. Every place exists only in its relation to its surroundings. This work is a record of my own journeys through Tokyo. Each of the three separate trips (Kannai to Meiji-jingu, Harajuku to the Kanda second-hand books area, and Ochanomizu to the Ueno Zoological Gardens) are presented in the form of a handkerchief, a ubiquitous Japanese object that has intrigued me, becoming a personal, pocketable guide, a map of my unique experience. Namrata Krishna. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: No Address Namrata made a series of ‘handkerchief maps’ that were based on her identification of prominent street level landmarks, objects and activities she witnessed as she traversed the same routes everyday in Japan. Instead of a conventional street map consisting of abstract symbols, her maps recorded her visceral encounters with these places and served as her personal mnemonic devices. They became important points of orientation for her. The handkerchief maps were also much more convenient and could be kept close to the body when she traveled. Stuff Wrapped This project encompasses both the art of collecting and wrapping. The idea of creating something out of trash and found objects is important to me because I find it rather challenging to avoid consuming and spending. As I walked through Japan, I began collecting a series of objects that I found interesting as a way to log my experiences. The collection lasted for 12 days and is composed of both man-made and organic materials. I began collecting even though I was not sure what I would be doing with the stuff that I kept accumulating, but I knew I wanted to create a project of this collection as a way to map my time in Japan. The work displayed is my collection wrapped. No longer is the object important, but rather, it is about the wrapping of the object. The form of wrapping corresponds to the object itself and the number of times an object is wrapped corresponds to the day it was found. One may find themselves unwrapping something up to 12 times only to find something in the center that is very much unimportant or to find nothing in the center. As Roland Barthes mentions in Empire of Signs, one can spend a long period of time unwrapping. It creates a sense of excitement and wonderment as to what will be found underneath, but once the center is reached, the object is often insignificant. Nirvine Tawancy. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Packages Nirvine's method of wrapping took into consideration the forms of the empty containers and packages as well the days they became trash. These ‘wrapped stuff’ were given a second life later when they were offered to the visitors as gifts. Instead of a two dimensional map, Nirvine’s map was a daily physical record of her consumption patterns. It was a map not made to record for posterity as it gradually lost its overall body and disappeared into the circulation of stuff again when each piece was given away. Impact Investigation This project is a mapping investigation of an impact. The day trip to Hiroshima I made last week left me emotionally exhausted. However, over the days after my visit I began to think about a couple things. I was struck by the idea that the atomic bomb gave a center to the city. A large dot was burnt forever onto the map of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The staggering imagery of the aftermath showed the “perfect” plane that was created from the destruction. The city is now a thriving, pulsing metropolis. However, its identity will forever be connected to this mark on the map. These ideas compelled me to create this mapping project. Square shaped rice papers are attached with red tapes to form a larger square and placed inside a box, lining the interior. A light bulb filled with Sumi-e ink was then dropped from eye level into this box. After drying, the rice papers were removed from the box and pinned on the wall. A plan and four elevations recording the impact were ultimately produced. The + shape of the panels recalled the crosshairs used for targeting. The resulting pattern created from the ink was a reference to the maps charting the destruction of Hiroshima. The red crosses stitching the grid together called to mind haunting images of the thousands of victims being treated in the aftermath. The glass shards left in the paper recalled the pieces of glass that survivors had to lived with in their bodies for years after the explosion and continued to be removed from people even today. Gabriele Muracchioli. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: The Writing of Violence Interpreting the map as the creation and residual of a violent action, Gabriele’s work addressed the destructive impact and continuing horrors caused by the atomic bomb during the Second World War. Coincidently, when the work was flattened and presented on the wall as a map, it resembled both the crosshair of a target and how a kimono, a Japanese traditional dress is displayed in a museum. In this case, however, one that revealed an absent and violated body. Disorientation and Discovery Japan is a system that has been perfected, but is often opaque (and intriguing) to an outsider. My experience of Japan has been a constant attempt to decode this system – a desire to decode it because of its precision, deliberateness and beauty. Here, days have been filled with long journeys – often exhausting, confusing and frustrating – that are punctuated by moments of serenity, discovery and awe at the beauty and perfection of something experienced for the first time. These moments are when I feel closest to comprehending the intricate system that is Japan. Yet, the journey is as important as the destination in coming to know this country Audry Grill. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Center-City. Empty Center Combining her fascination and daily encounters with the Tokyo’s subway system, Audry created a map consisting of a network of colored lines in the ZAIM studio space that ran across floors, down the stairs and around the walls. The lines led to and highlighted objects that the students passed by everyday but overlooked during their stay in ZAIM. Some lines ended abruptly. The map echoed her experience of navigating through the labyrinthian spaces in the city that was filled with occasional annoyances but revealed unexpected discoveries as well. Greasy Japan Sweating has been a perpetually consistent aspect of my visit to Japan. For each day that I was traveling about, I would find time to blot my face with blotting papers purchased from the Muji counter of the local Family Mart. The shape and size of the grease stain left on the blotting paper changes in size as well as the quality of transparency- the outline defines the area of the stain left behind, tracing the amount of grease and sweat I produced at that time, day and location. Changes in humidity levels, increase in activity, the location’s climate, and time of day affect the differences of the shape and size left on the paper. Patterns from the first few days have gradually disappeared over the course of my stay- perhaps evaporating or absorbing into the paper leaving no trace of grease and sweat on the paper.Documenting this temporal aspect and change from one period to the next has become an important aspect for me, and my visit to Japan. Rebecca Midden. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: The Written Face Becky transformed the pieces of blotting papers she used throughout the trip into a map that recorded the patterns of grease stains on her face. She noticed that depending on the time of the day and night, and the activity she was engaged in, the size of the stains varied. The stains were carefully traced over with a pencil. One could read from each map the intensity of each activity during the trip and collectively, they presented a fascinating alternative map of her stay in Japan. However, it was also an ephemeral map where the tracings of her earlier sweat territories gradually disappeared as her stay in Japan continued. Headlines The sameness of the airport, its blandness, its sterile nature, is a misleading welcome to Japan. Once the luggage has been picked up, gone through immigration, passed through customs and exited the terminal, all mundane and expected processes of travel, do you get a whiff of the foreignness of Japan. It is more than the language, or the driving on the other side of the street. It is about the respect afforded to strangers, it is about the reverence of the old, of past customs that live side-by-side with modernity. It is about the attention given to the most minute and seemingly insignificant of things. Language has been a barrier; a barrier that has allowed for better understanding. It is a contradiction that is hard to explain unless it is personally experienced. This project is about that occurrence—of being unable to fully understand someone or something, of perception and assumption, of understanding on a level notwithstanding language Jaime Rovira. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: The Unknown Language Jamie’s mapped the lost in translations between pictures and the Japanese text in daily newspapers. Despite the saying that a picture speaks a thousand words, it does not mean an accurate correspondence between a picture and its text in his case. Using a combination of yellow Post-It notes and strips of paper, Jamie attempted to ‘read’ the images accompanying the local headlines of the newspaper at the hotel every morning. During the exhibition, he also encouraged the visitors who do not speak the language to try and interpret the pictures in the newspapers. The process often led to very different outcomes, ranging from the absurd to the hilarious. Untitled This project maps an impression of my experiences in Japan by recording the everyday; the persistent shift between awkward and peaceful feelings. How our consumption and understanding of copious travel maps differ from our experience of a place, and how we process this information into memory. My interest in the rituals at the shrines and the collection of advertisement magazines led me to create these strips as a release of these impressions and feelings. Kirsten Hanson. Master of Architecture(2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Animate/Inanimate Taking the promotional magazines and pamphlets given freely along the streets, Kirsten folded them into the shape of a wishing tree and suspended it from the ceiling. Visitors to the exhibition could add their own wishes by attaching them to the tree. Whether wishing for good health, world peace or a new car, the tree accepted them without any discrimination. When a visitor added a wish, the movement of the body created a slight breeze that momentarily animated the wishing tree, as if it acknowledged the receipt of the wish. Map To journey through Japan is to walk paths that are less than linear. This project is about mapping this journey, limiting Japan to what I have witnessed and traversed. Maya Janczykowska. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: No Address Maya’s map fused her experience of vulnerability being in a foreign country without any knowledge of the language and customs as well as her difficulty in locating places while navigating the streets in Japan. This persistent experience brought into focus her memory of the streets more than the actual places she was supposed to find. Her maps were made by carefully cutting out the places visited, leaving only the lines of streets visible. In the chapter No Address, Barthes offered a different reading of how we orientate in a city; not by maps but through our bodies and memories. In the Middle Delicate. Fragile Enveloping. Folding, Surrounding. Weaving old and new Completing your soul. Fulfilling sense of peace and Overwhelming notions of grace. Extreme oppositions And soft light compose, Symphonies of unattainable qualities. What is real? Messy realities of history, past Through the soft light comes A progressive future. Confrontation with present violence Stirring overwhelming sense of peace We are those exact opposites Surreal moments that permeate Miserable vitality Spiritual depression Where is the boundary? Somewhere in the middle We meet. The black and white mix, Creating pages of text… That line our souls with: Ambiguity. Annie Kasper. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Millions of Bodies Annie’s map of Japan consisted of folded rice paper that twirled itself across the walls of the ZIAM studio. The map was made by repeating the same folding pattern over a specific period of time. Although similar in form, each piece became slightly deformed as the overall form negotiated across the walls. The map marked a moment of her stay in Japan and also alluded to the Japanese aesthetic of lightness and ephemerality, which Barthes described as running ‘from difference to difference, arranged in the great syntagm of bodies.’ ((((((((( ))))))))))) As travelers we scavenge (((((((((( ))))))))))). Memory is both fantasy and reality. We consciously seek and we unconsciously surrender. The intention of Haiku is revealed in essence while the structure is released. The project attempts to map the evidence of (((((((( ))))))))))). Brandon Styza. Master of Architecture (2009) Kimberly Richter. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Without Words Kimberly’s and Brandon’s collaborative map-making project was a multi-media map of Japan. Brandon brought along with him to Japan his headphone and microphone which he meticulously recorded a series of everyday sounds throughout the trip. Sometimes he would wander away from the group or was left behind because he was so captured by the soundscapes around him. Both students later resampled them into a soundtrack that accompanied the moving images. The frenzied combination of images and sounds presented a rich and layered map-in-motion of their experiences in Japan. The Interstice Japan has been a study in contrasts- contrasts that are not clearly defined but blur, shift, transform and transport. It has shifted my thoughts as I consider the relative static-ness of my own culture. This project questions the line or the lack thereof between the sacred and the mundane. It explores the idea of sacredness as transitory- as not attached to place but rather to the process of moving through space. It is about intentionality rather than being in a particular place in time. From the ever-shifting shrines at Ise, to the temple thresholds stepped over at Nara, to the blurred separation between the floating Torri and its own reflection at Miyajima, this idea and feeling of temporality is all at once off-putting, appropriate and beautiful. Where does sacred space begins, ends, overlaps with the mundane? Do they lie in contrast or exist together in what Roland Barthes refers to as the interstice- to being “without specific edges” that is nowhere and everywhere. Sarah di Nicola Tranum. Master of Design in Designed Objects (2009 Empire of Signs chapter: The Interstice

Intrigued by the interweaving of the secular everyday life with the scared, Sarah Tranum made three light sources and placed them the floor. They were accompanied by a porcelain dish, a chalk stick and a note set on top of a simple wooden box. The note asked the visitors to draw a line demarcating the boundary between light and darkness around each light source. Using the metaphor of light and enlightenment and the circuitous body of lines, Sarah’s work revealed the visitors’ shifting, ambiguous and individualized boundaries between the spiritual and the secular. In 2009, I received the Japp Bakema Fellowship from the Netherlands Architecture Institute for my project ZERO. It was the height of the Great Recession and architects were laid off by the droves daily in Chicago. My architecture students who recently graduated were unable to find work or had to take up odd jobs to make ends meet. As an architect and a teacher, I came to realize the limitation of an architectural education that resides within an academy and cut off from the larger society, which architecture students will eventually be part of. I was dismayed by the narrow definition of architecture, the limited contributions of an architect besides a building, and the traditional client-architect relationship in practice. I saw the Great Recession as an opportunity to re-evaluate and re-frame architecture education and the role of an architect in society.

The fellowship afforded me the financial resources and time to research and document the various manifestations, causes, and meanings of emptiness, the values of unbuilding and how the local residents in Asian cities, many who were living along the margins of society, were able to occupy empty spaces for different durations and for social, commercial and personal uses. It opened my eyes to their ingenious, opportunistic, and informal use of empty spaces, found materials and urban infrastructures to fulfill their daily needs. Through ZERO, I discovered the relational dynamics of their occupations and actions, which were attributed to their creative use of scarce resources, and their ability to adapt, negotiate and utilize social relationships and existing spatial contexts to their advantage. Their occupation tactics were both a form of resistance and an adaptation to the planned spaces in the cities. I was fascinated by the spatial intelligence and material resourcefulness of the residents despite not receiving any formal design education. Its radical design amateurism and material relativism driven largely by pure purpose and need challenged what I learned in architecture school and the canons of good design. ZERO discovered the under and unrepresented everyday beauty and the potentiality of society’s detritus, be it material, social, cultural or spatial. The casual juxtaposition of the planned and spontaneous, the new and the discarded questioned our conventional notion of authenticity. The creative re-using of cast-off objects and materials by the residents was also a consoling knowledge in an age of throw-aways. ZERO was a timely springboard for my own search for an alternative design education and practice at a time of economic crisis, as well to broaden what an architect can contribute to society besides another building in a post-economic bubble age. Curapolis casts curatorial practice into the public realm by combining an advocacy role and the examination of contemporary urban culture and spaces. By looking at the city as collections to be examined, curated, disclosed and directed towards future actions, Curapolis differs from current curatorial projects in three ways:

1. Curating as Agency As an act of advocacy, curating is an important stage in the process of activating participation, gathering and advancing ideas, as well as crafting strategies that can bring about meaningful change in how we conceive, design and live in contemporary cities. 2. Curating in an Accelerated Time and a Networked Culture Curapolis recognizes the phenomenon of an accelerated time in the 21st century while living in a networked culture means ideas multiply, connect, splinter and reform in myriad ways. How we respond meaningfully to the pace of transformation, plurality of voices and democratization of curating brought on by the Internet is critical in uncovering new curatorial and spatial possibilities. 3. Curating and the City Walter Benjamin’s unfinished Arcades Project could well possibly be 20th century's first example of how the experience the city is a curated collection of categories. Curapolis draws inspiration from Benjamin’s novel approach in understanding the city of his time but aims for a broader and cross-disciplinary focus. I was invited by the Hong Kong Council of Social Service to a sharing session among community and social workers, designers and academics in Sai Ying Pun. It was an inspiring experience to learn of their interdisciplinary approach to tackle social issues through design and the arts. On my part, I presented the concept of Social Archiving as a public platform where socio-cultural memories and artifacts can be shared, care for and sustained for communities facing redevelopment. The event was held in Magic Lanes, a community lab set up by Caritas Hong Kong with a mission to serve the residents living in the district through asset based community development.

Ceil Balmond, OBE spoke of structures as the 'punctuation of space, episodic and rhythmic'. It's not unlike how a poorly placed period or comma in a sentence can ruin a sense of gravity or lightness. His way of looking at structures re-establishes the relationship between structures and life- with the breathing, living and rhythmic body.

My 5 min presentation for the event on Sep 16, 2017 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

The airport fascinates me as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Seldom do you find gathered in a building such a diversity of nationalities and cultures. In this slide, you see the Goddess of the Sea, Mazu and her 2 Heavenly assistants taking a business class flight from China to Malaysia for a religious event. They were issued boarding passes too. Future innovations will need to recognize and address the needs and experiences of a diverse group of travelers and users. In Singapore, the Changi Airport is a destination for the young and old who come to the airport for a variety of reasons. So much so that Changi may be the only airport that has so many signs discouraging students from studying. Changi is more than just an airport to the locals. It is a third place, a term coined by Ray Oldenburg to describe a place that people gather that is neither a home nor the office. First impressions count. The Copenhagen Airport is a showcase of Danish design. On the other hand, during the design of the Changi Airport in the 1970s, the Prime Minister then instructed the planners to plant rows of rain and palm trees along the highway leading from the airport to the city center, and that they be well maintained, for 2 reasons. First, it conveyed to arriving visitors that this is the tropics, and secondly, a signal to potential foreign investors that the city-state is well managed and the right place to invest their money in. This first impression was designed to reach a high point when the towers of capitalism, hidden by the trees, unfolded before your eyes as you reached the highest point of the Benjamin Sheares bridge after a 15 min taxi ride from the airport. Vice versa, the experience of the airport starts before arriving at the terminal. The in-town check-in service in Hong Kong is a good example. It gives back some control of time to the travelers who have to negotiate an environment that encourages consumption yet tightly controlled and surveilled. I believe designing the experience before and after the airport is as important as the airport itself. "My work depends on engineers, on electricians, and on a number of other specialists. And, in my office, I have more than twenty-five architects, so it's not very solitary. But, periodically, during the process of a project, I take home the drawings and I need to concentrate not only on designing and sketching things, but on really knowing the building, really knowing the project. I have to be able to walk through the whole building mentally without looking at the drawings, you know? I have to be able to sit and imagine walking through the building, going down each hall, entering the bathroom, washing my hands, going to the kitchen if it is a house. And if it is a public building, this can indeed be difficult. But I make every effort to study the project as it develops. Only when you can walk mentally through the building can you design the final details and can you feel the atmosphere of that building and what it really means. For this, I need moments to concentrate by myself, alone. In the office, this is not too easy because there are telephones, visitors-and interviews. But I can go home and sit alone and reflect."

Alvaro Siza Vieira. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.artic.edu/docview/1874001408?pq-origsite=summon "As much as poetry and literature, architecture is about relations between things and about passages from one to the other."

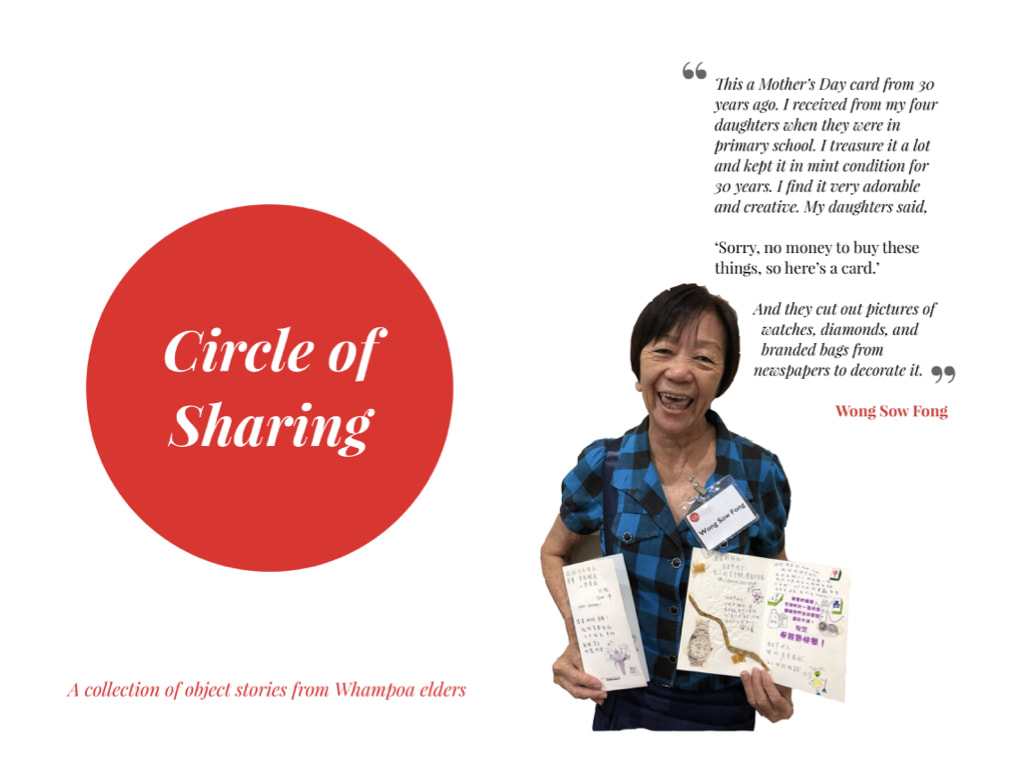

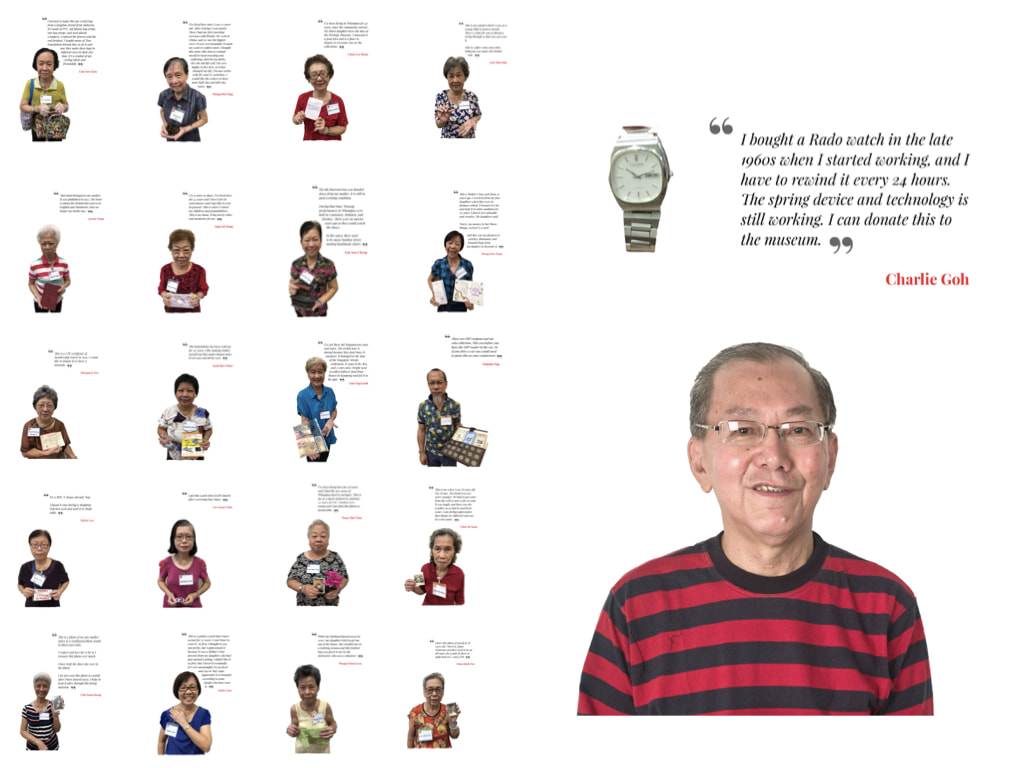

Alvaro Siza Vieira. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.artic.edu/docview/1874001408?pq-origsite=summon During the first day of the facilitation session in To Kwa Wan, I introduced the Circle of Gift Giving to the group. Sitting in a circle, each participant gave a small present to the person seating next to him or her. The ritual required the gift giver to share the source and meaning of the gift to the receiver. As the circle of gift giving enfolded, we shared funny, down to earth and poignant stories behind each gift. One participant forgot to bring a gift and she bought one in To Kwa Wan. Being practical minded, she bought a bottle of WD 40 from a car repair workshop as a gift and hoped it would be useful for the gift receiver. Another female participant gave a movie ticket to the participant next to her. She explained that it was from a movie date but her partner failed to turn up. She ended up leaving the movie theatre holding the unused ticket. A participant gave a small coin, which came from a memorable trip to Taiwan she made with her father, while another gave an old high school exercise book. She shared that the book brought back memories of her school days in Hong Kong after being away for many years.

The participants had to learn from the sociocultural and economic life of To Kwa Wan residents, and come up with interesting ideas to archive the fast disappearing neighborhood over a one-month period. They came from all walks of life and were strangers to each other. Before diving deep into the task, I felt it was important to first form a community of learners through the ritual of gift giving. As Lewis Hyde in The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World so eloquently wrote, "...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears.” I was invited by the Make a Difference School in Hong Kong to be a guest facilitator for their 1- month in-situ studio in To Kwa Wan. Over 3 days in August, I gave a public lecture on the concept of Social Archiving and conducted discussions with the participants and local residents on the future of the neighborhood that was slated for re-development. Looking at To Kwa Wan superficially, one sees only the large number of car repair workshops, and would not have imagined a rich and diverse collection of social relations and history. Through my street conversations with the locals, I discovered a resident who played the flute to entertain passerby and gave a very good impression of singing birds. There was a pastry shop that have used the same 40-year old recipe since the day it opened for business, and even a car repair workshop that doubled up as a daycare for the child of a single parent who had to work part-time.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed