|

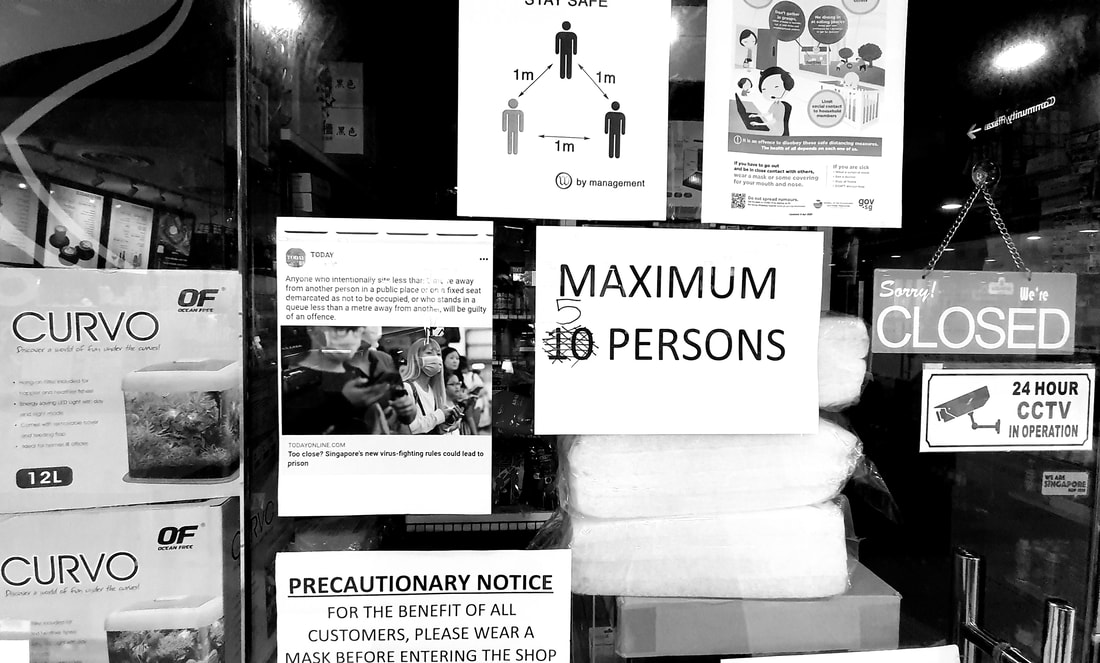

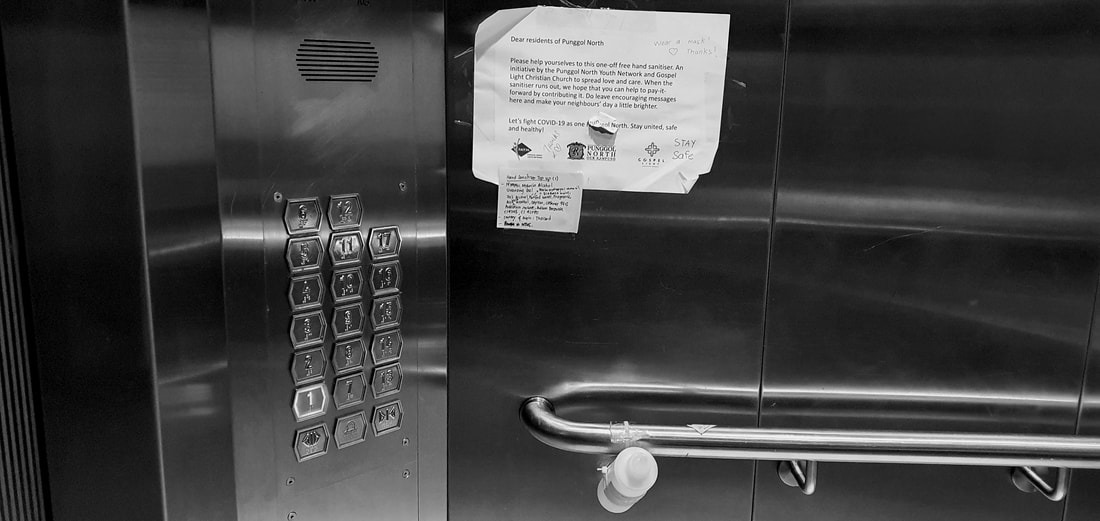

The Covid-19 pandemic has challenged and uprooted our lives in ways unimaginable on a global scale. When cities are locked down for an extended period and their inhabitants told to stay home, these unprecedented social restrictions are counter to our fundamental way of life. For personal safety and social responsibility reasons, careful considerations now intercede simple, everyday interactions that we take for granted before the pandemic.

In 2009, I received the Japp Bakema Fellowship from the Netherlands Architecture Institute for my project ZERO. It was the height of the Great Recession and architects were laid off by the droves daily in Chicago. My architecture students who recently graduated were unable to find work or had to take up odd jobs to make ends meet. As an architect and a teacher, I came to realize the limitation of an architectural education that resides within an academy and cut off from the larger society, which architecture students will eventually be part of. I was dismayed by the narrow definition of architecture, the limited contributions of an architect besides a building, and the traditional client-architect relationship in practice. I saw the Great Recession as an opportunity to re-evaluate and re-frame architecture education and the role of an architect in society.

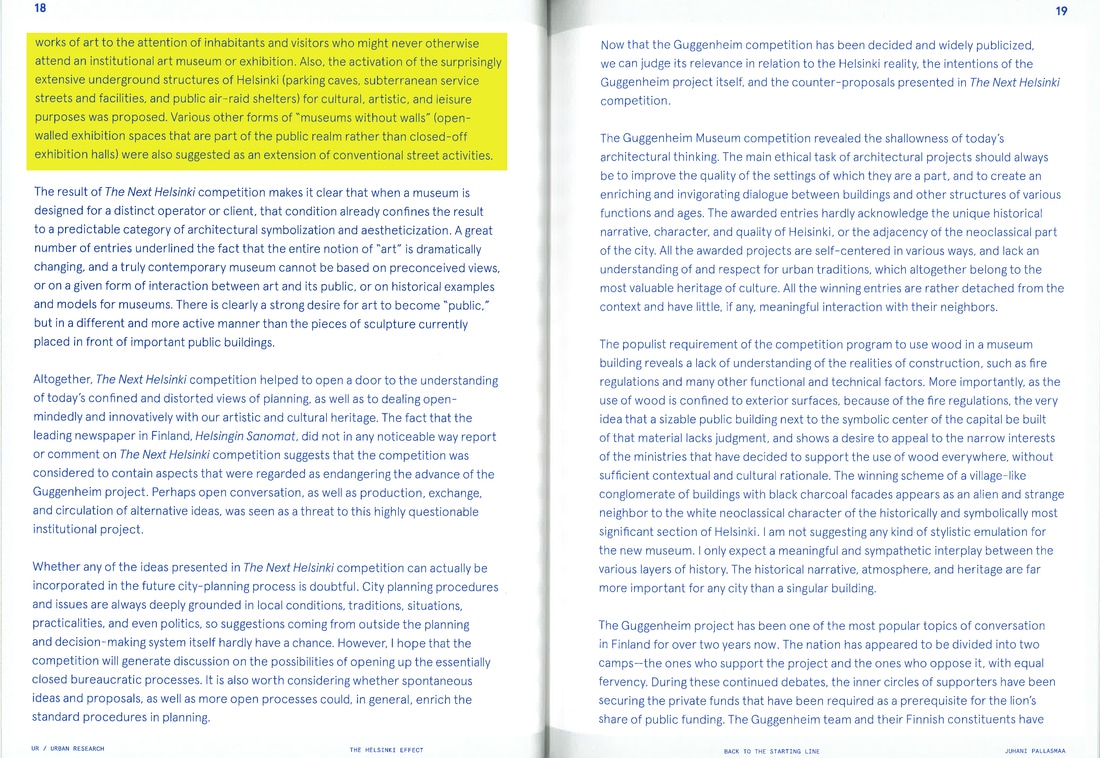

The fellowship afforded me the financial resources and time to research and document the various manifestations, causes, and meanings of emptiness, the values of unbuilding and how the local residents in Asian cities, many who were living along the margins of society, were able to occupy empty spaces for different durations and for social, commercial and personal uses. It opened my eyes to their ingenious, opportunistic, and informal use of empty spaces, found materials and urban infrastructures to fulfill their daily needs. Through ZERO, I discovered the relational dynamics of their occupations and actions, which were attributed to their creative use of scarce resources, and their ability to adapt, negotiate and utilize social relationships and existing spatial contexts to their advantage. Their occupation tactics were both a form of resistance and an adaptation to the planned spaces in the cities. I was fascinated by the spatial intelligence and material resourcefulness of the residents despite not receiving any formal design education. Its radical design amateurism and material relativism driven largely by pure purpose and need challenged what I learned in architecture school and the canons of good design. ZERO discovered the under and unrepresented everyday beauty and the potentiality of society’s detritus, be it material, social, cultural or spatial. The casual juxtaposition of the planned and spontaneous, the new and the discarded questioned our conventional notion of authenticity. The creative re-using of cast-off objects and materials by the residents was also a consoling knowledge in an age of throw-aways. ZERO was a timely springboard for my own search for an alternative design education and practice at a time of economic crisis, as well to broaden what an architect can contribute to society besides another building in a post-economic bubble age. I was invited by the Make a Difference School in Hong Kong to be a guest facilitator for their 1- month in-situ studio in To Kwa Wan. Over 3 days in August, I gave a public lecture on the concept of Social Archiving and conducted discussions with the participants and local residents on the future of the neighborhood that was slated for re-development. Looking at To Kwa Wan superficially, one sees only the large number of car repair workshops, and would not have imagined a rich and diverse collection of social relations and history. Through my street conversations with the locals, I discovered a resident who played the flute to entertain passerby and gave a very good impression of singing birds. There was a pastry shop that have used the same 40-year old recipe since the day it opened for business, and even a car repair workshop that doubled up as a daycare for the child of a single parent who had to work part-time.

"...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears."

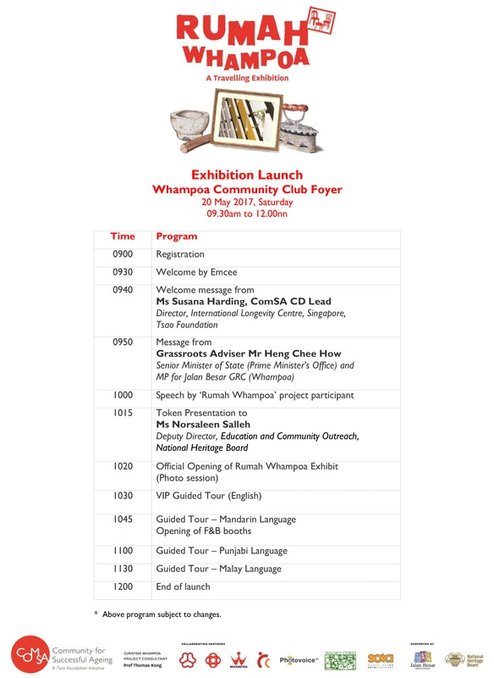

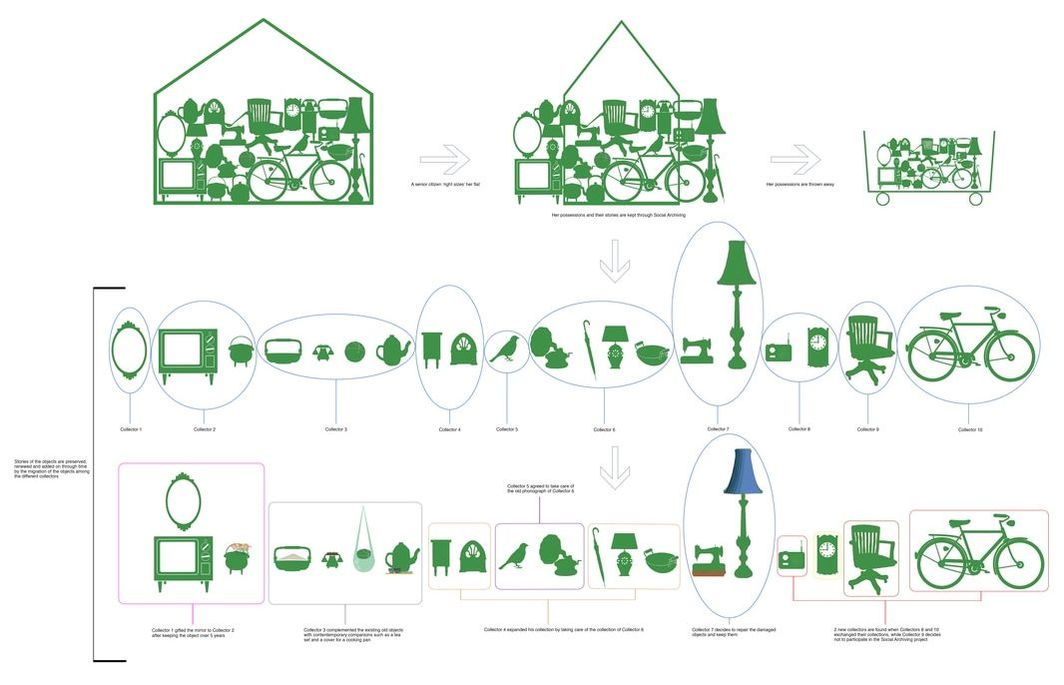

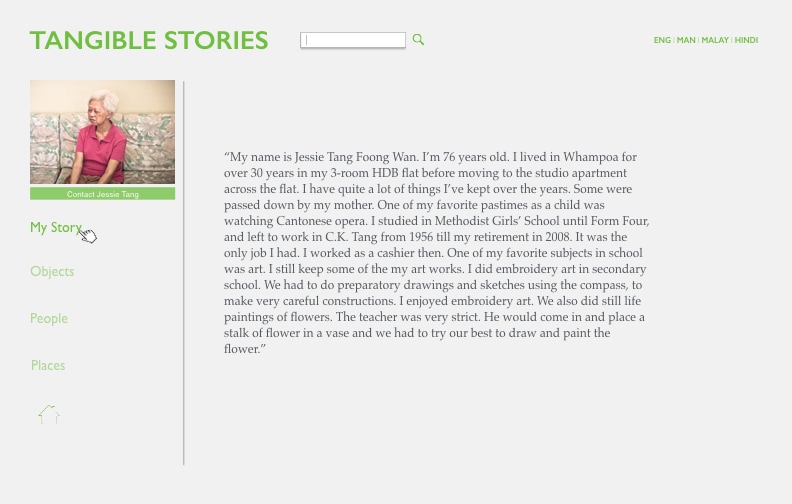

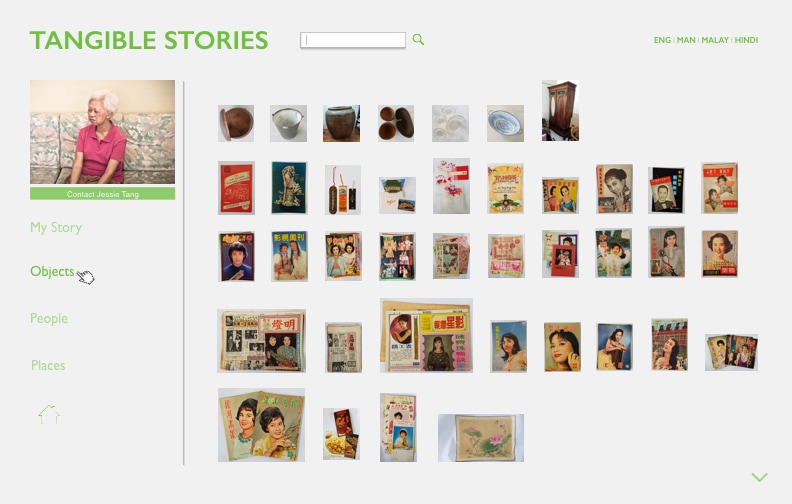

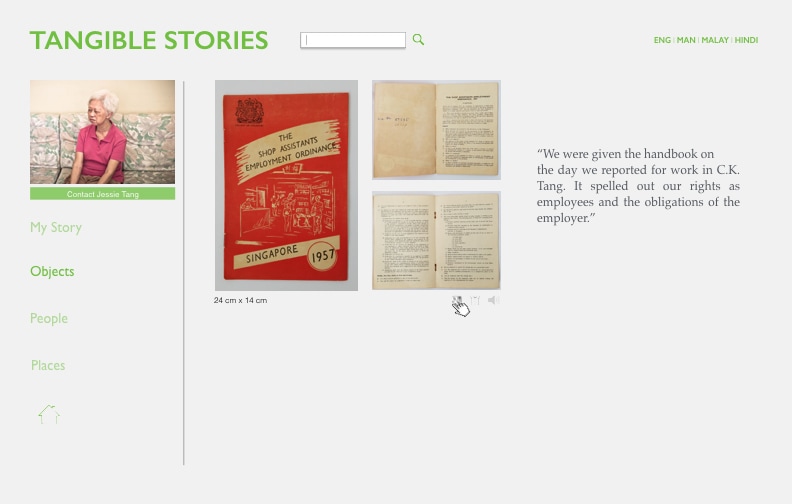

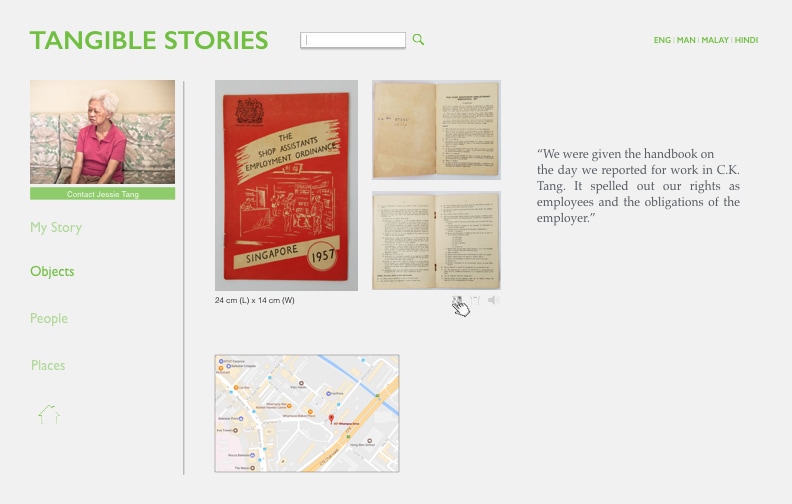

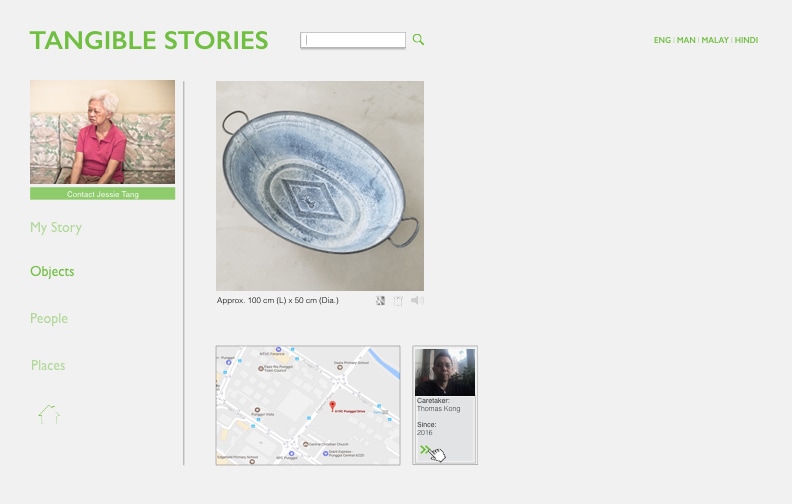

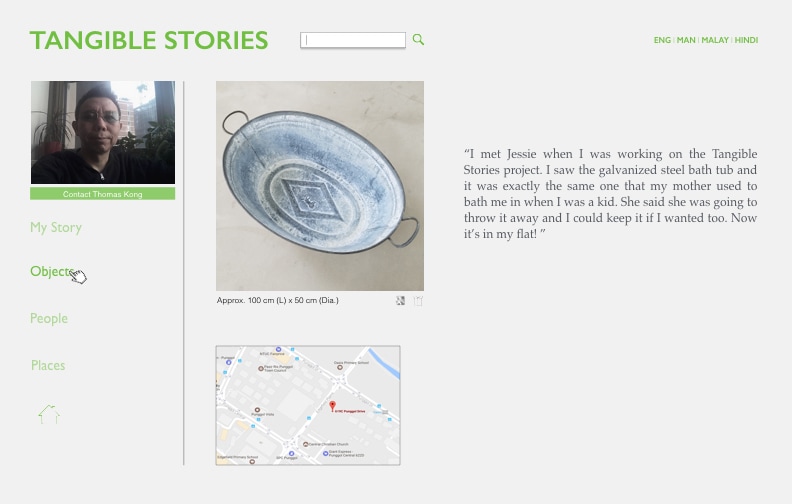

Lewis Hyde. The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World. Social Archiving explores a new form of archiving that combines gift giving, safekeeping, curating, placemaking and a renewal of the life of a collection through a simple in-person ritual and a digital interface for sustaining the social life of the collection nationally and beyond. I conceived of Social Archiving as a new model of caring for objects and ephemera that carry cultural and heritage value. It is a platform for intergenerational learning in-place and online, public stewardship and the building of a personal legacy through the sharing of the stories related to the archived materials. Social archiving was motivated by the diminishing size of an elderly’s home and a rapidly aging population in the city-state. Social Archiving draws from the rich tradition of archiving as an art form and differs from current institutional model of archiving in the following ways: 1. It is interdisciplinary. The process in itself constitutes a participatory form of art-making and sharing. 2. Although Social Archiving has a precedent in the rich tradition of archival art, it does not rest purely as a one off art project. Social Archiving helps in the crafting of interactions and relational structures in the design of spatial strategies to address contemporary urban concerns. Specific to this proposal are the issues of aging in place, personal legacy, identity, community forming and the spaces that support them. 3. It relies on the interest, passion, care and housing offered by a community of volunteer archivists/collectors/curators instead of the control and management of an institution. 4. It promotes social interaction, both digital and in real time in the archival process. 5. It encourages active, creative re-interpretation and curating of the archived materials that extends beyond the passive role of offering a storage space. 6. It recognizes the role social media plays maintaining contact between archivists, between the original owner and the new collector, and in the organization, dissemination and sharing of the archived materials. 7. It permits the transferring of the archived materials if the new collector agrees to the role and expectations. 8. It is a scalable process that can range from an intimate social setting to a large, community-level interaction. The populations of Asia and Western Europe are rapidly aging and 60% of the world's population is in Asia. Although the project is situated in Singapore, the issues, challenges and opportunities surrounding aging are global while the initiatives to address this rising societal phenomenon are potentially transferable to other nations. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/what-singapores-plan-for-an-aging-population-can-teach-the-us/2015/11/01/f86e9596-7f42-11e5-b575-d8dcfedb4ea1_story.html) Singapore is a particularly important case study because it has one of the world's fastest aging population. Over 80% of its population lives in high rise public housing given the limited land available for development. As the government encourages its citizens to see their apartments as economic assets, it is not uncommon for many to sell, buy and live in several apartments over their lifetimes. Each move generates bigger profits that serve as their retirement nest eggs. Through my encounter with the senior citizens in the course of the Tangible Stories project, I foresee the Social Archiving project can take on a significant role in the social and cultural landscape of Singapore based on the following reasons: 1. As more and more senior residents move into nursing and retirement homes, as well as smaller studio apartments, they are confronted by the challenge of holding on to their cherished possessions acquired over the years. These possessions include furniture, objects for daily use and print materials that house strong memories for them. Unfortunately, many senior citizens have to either sell or throw them away now, especially if they are single or do not have children to pass these objects and materials to. Moreover, some of their children may not be keen to take over their parents’ possessions. 2. Given the unceasing urban transformation and the rapidly aging population in the city-state, many grassroots level memories are lost despite the attempts to collect them through the massive, national-level Singapore Memory Project. Social archiving offers a more intimate platform for intergenerational learning and remembering through the sharing of the stories related to the archived materials. As Arthur C. Brooks in his Op-Ed piece for the New York Times wrote. "One million is a statistic. One is a human story." 3. As more and more studio flats are designed within existing and matured housing estates, there is an urgent need to give greater consideration to the design of public spaces that promotes aging in community. Besides design considerations such as universal access, elder friendly interiors, etc., the provision of spaces and the holding of community events that help anchor personal memories of place can be promoted through social archiving. Partners: Jacelyn Kee; Lee Sze-Chin; Asian Film Archive; Tangs Holdings; Tsao Foundation. I often look back to the Chinese language in order to see things anew. The word mobility comprises of two characters, one refers to 'grain' and 'many', while the other to 'clouds' and 'force/energy'. Grains and clouds- the earth and the sky- How poetic! We use the terms 'Cloud Computing' and 'Cloud Storage' now to suggest the freedom and ubiquitous nature of computing and an era of unlimited digital storage. One is no longer tied down to a specific object or is accessibility limited.

Clouds do not have definite edges or shapes and they do not recognize boundaries. Clouds drift. Clouds are not bubbles, which are hermetic, sealed off from the world. Clouds receive, collect and hold until their formless states become tangible falling clouds when they could not resist the force of gravity. The falling clouds from the sky nourish the life of the grains that in turn sustain human life on earth. Metaphors are still important, just like how Louis Kahn and Ann Tyng re-directed our understanding of traffic flows, buildings and infrastructures in their traffic study of Philadelphia with a new notation system and by calling them rivers, docks and harbors. In Greek, a metaphor means 'to carry', to 'transfer'. Isn't that what we partake every day on the way to work, to pick up our kids, and back? Unlike a subway line that serves a singular function, I wonder how do we imagine a 21st C Mobility Cloud housing a multiplicity of scales, movements, durations and experiences that not only carries and transfers but also nourishes and sustains our wellbeing? The city is filled with people engaged in a wide variety of daily activities every morning- going to work, buying breakfast along the way, delivering goods and services, cleaning the shop front, waiting for the bus, etc. These activities occur repeatedly each day without fail, to the point of being involuntary like breathing. But their repetitions also instilled a sense of dullness and monotony. What happens when we reframe these ordinary activities as various forms art, ranging from public sculptures to performances? Will we begin to see and value them differently? Taken from Hong Kong one morning, the various objects and human activities reveal the rhythm and relationship of space, objects and people in the fast- moving city.

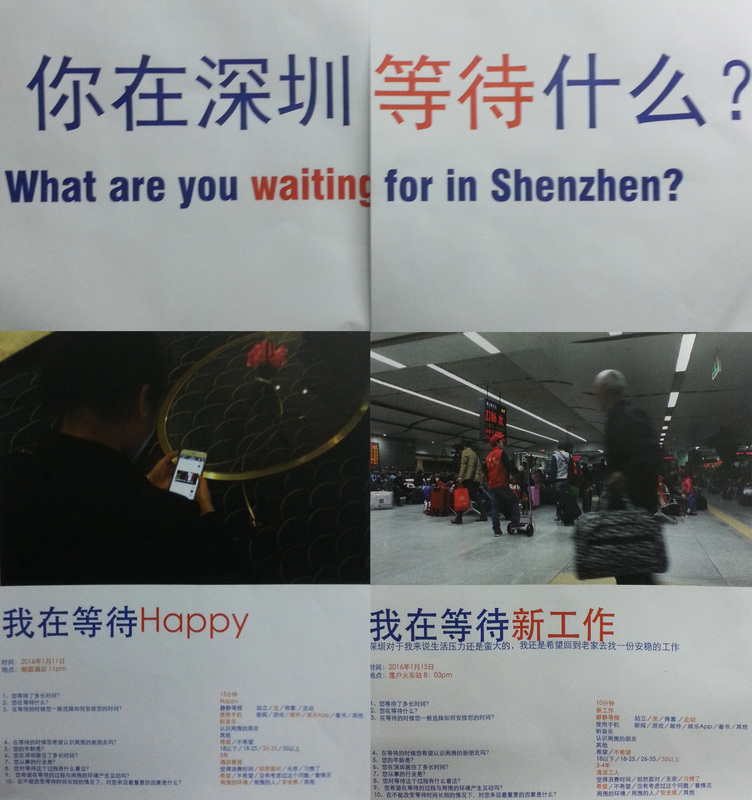

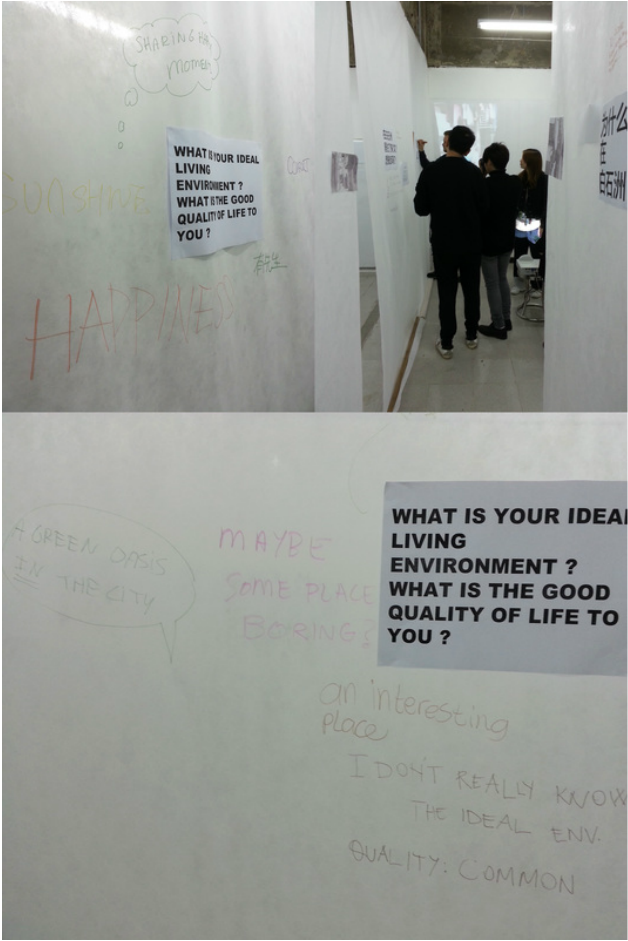

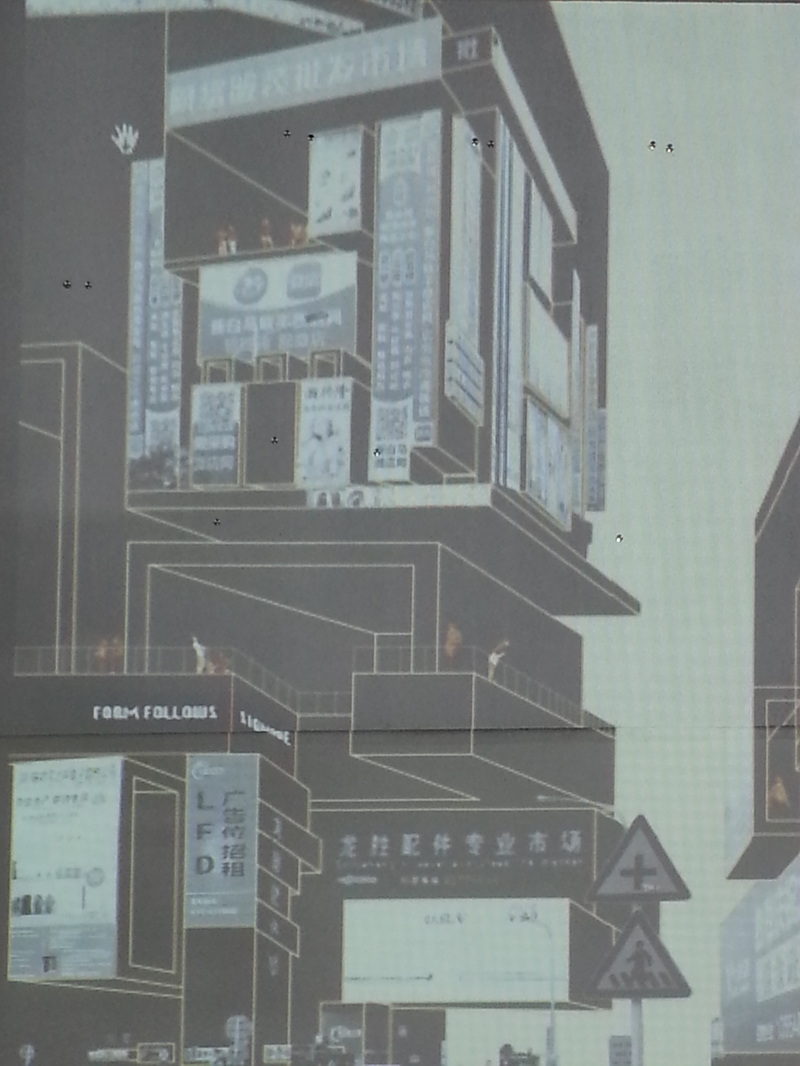

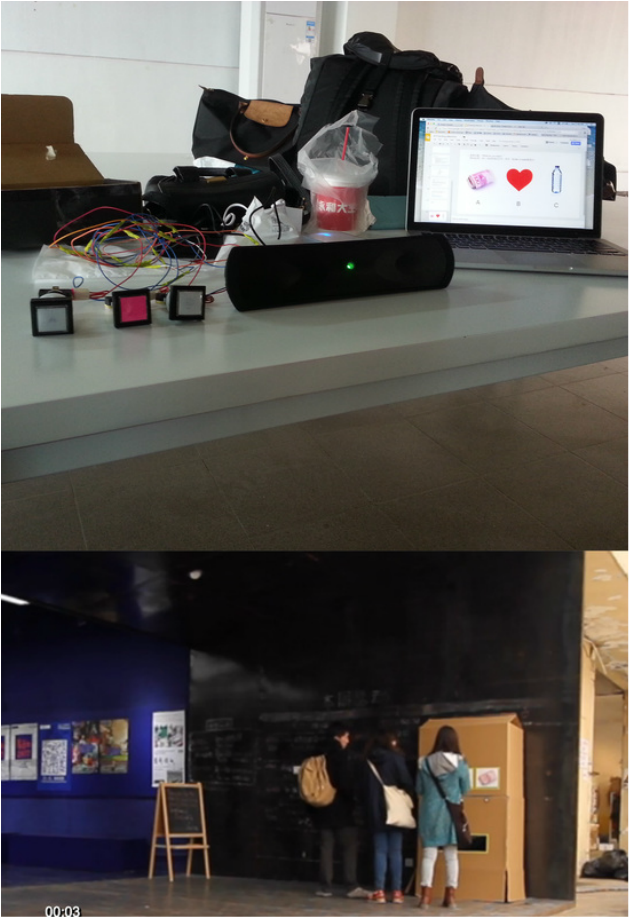

Learning from Shenzhen: The City as a Studio, was conceived and led by Thomas Kong. It formed part of a series of studios organized by the Aformal Academy during the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture. In this 5-day studio, participants were involved in a number of micro, on-site investigations centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in China’s first Special Economic Zone. Waiting Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work. Uniform The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority. Good life Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond. Form follows signage Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage. Shenzhen Vending Machine Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, the body and human relationship. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired. Drawing Memories

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life. The invitation from the Aformal Academy to teach a class during the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture in Shenzhen, China was a pleasant surprise and a serendipitous meeting of distant minds. I have just written a proposal for a fictitious design school that aimed to reimagine the current institutionalized structure and organization of the architecture and design education. The proposal was motivated by my desire to search for an alternative design pedagogy less organized around the long cherished model of a design studio housed in a school and be more engaged in a peripatetic experience situated within multiple locales in the city. The biennale in Shenzhen offered a wonderful opportunity to undertake such a pedagogical experiment. Titled, Relearning, the Biennale hopes to question the basic assumptions of the architectural artifact, design of cities and by extension their impacts on our everyday lives.

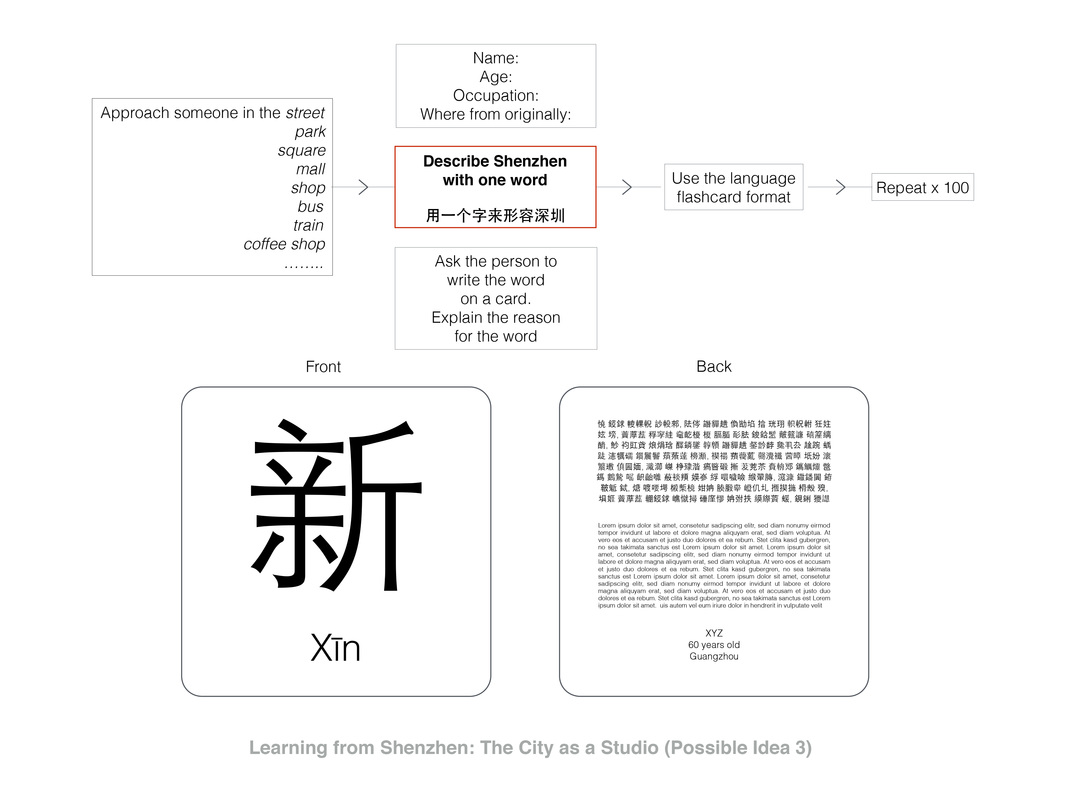

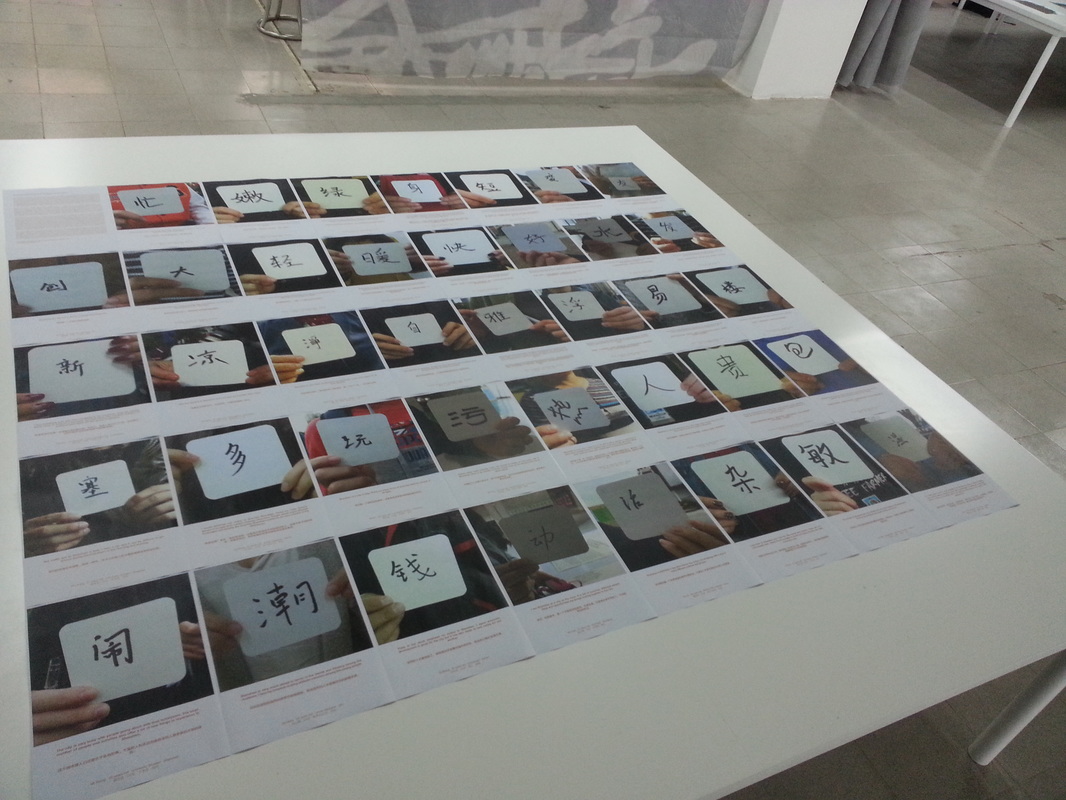

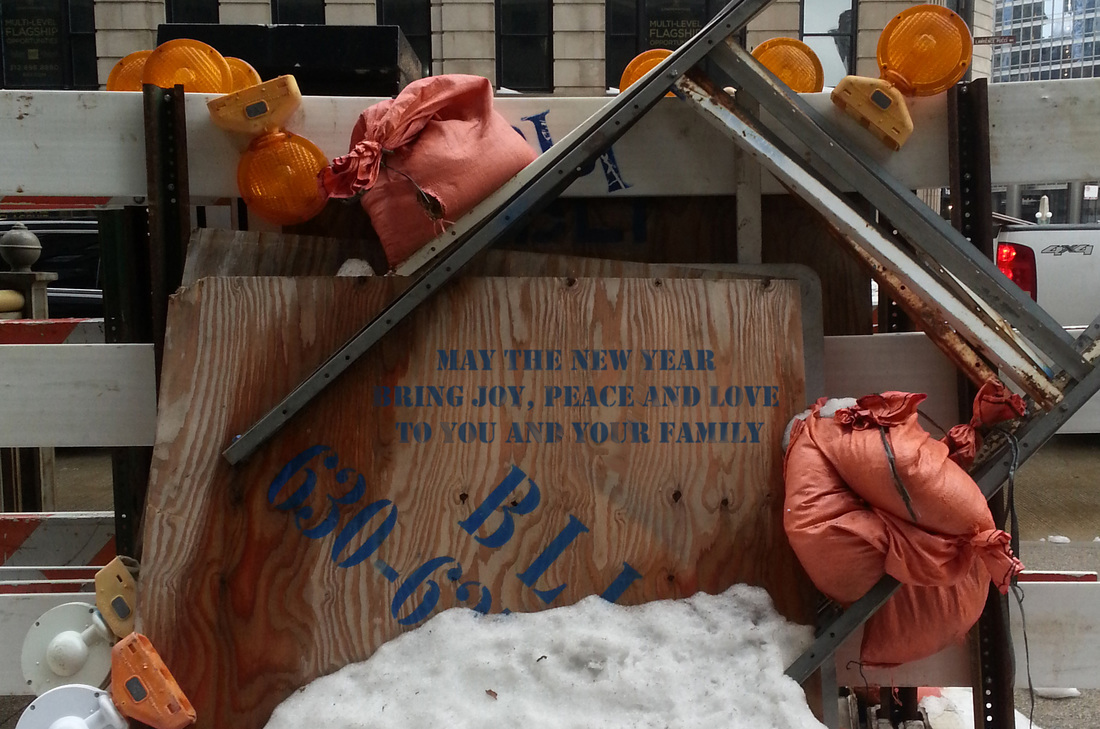

Much has been written about the meteoric rise of Shenzhen from a quiet fishing village to a modern metropolis after it was decreed by the late premier Deng Xiaoping as a Special Economic Zone. The multitudes of social, cultural, economical and environmental challenges that accompany such an accelerated urbanization process are also well documented. What more can we learn from Shenzhen? And who else can we learn from besides the mélange of professionals, experts, city officials, thinkers and observers of Chinese cities? In the spirit of RElearning, RE not in the Greek god Sisyphus’s sense of repetitive actions condemned to eternal futility, but one that could refresh and redirect our learning of Shenzhen. The Shenzhen Flash Cards Project carries such an aspiration. The RElearning happens at street-level and from the local residents through the process of crowd sourcing a Chinese character or字that best exemplifies the city at this particular point in time. The hand written character will be recorded on a flash card and the process repeated. The final collection of flash cards will consist of the accumulated handwritten cards over time. As a system of pictograms and ideograms, the Chinese language is most suited to this pedagogical experiment. The compositional meanings inherent in a Chinese character and its combinatory possibilities expand on what could first be perceived as a limited and narrow beginning. Like the use of flash cards to learn a new language, the city flash cards will hopefully offer multiple, drifting, colliding, commingling and shifting meanings of Shenzhen shaped by the forces of urbanization and globalization. The RElearning of the city through the Shenzhen Flash Cards Project does not proceed from a fully formed theory or will the eventual understanding be systematic, complete and unified. Rather the learner needs to interpret and filter a palimpsest of dreams, desires, fears and memories, which defies neat categorization and are ultimately fragmentary. In a sense, this is how a city appears to us and is experienced. It is conceived that the flash cards will have educational, economic and cultural afterlives beyond the Biennale. It could be used by schoolteachers to cultivate awareness among Shenzhen students the manifold values and perceptions of a diverse group of city dwellers. It could be sold as a memento in a gift shop, which offers visitors to Shenzhen something beyond a packaged touristic experience. It could also be housed in the library as an archival material for future learning and reference. Or it could simply remain on the shelf of an academic, tucked among an assortment of books, papers and other personal objects, to be rediscovered only after several years have passed. A wonderful sight on the way to work! A street vendor selling fresh fruits on the sidewalk. Summer is here, finally.

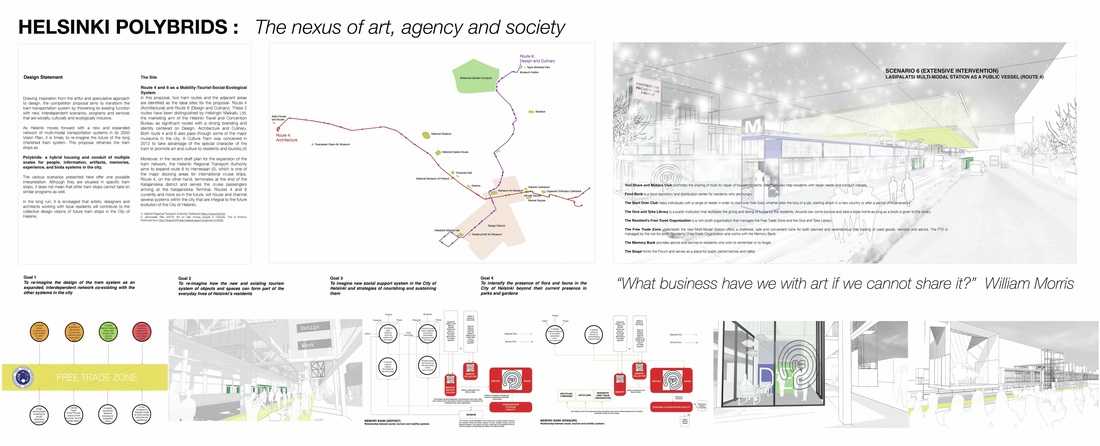

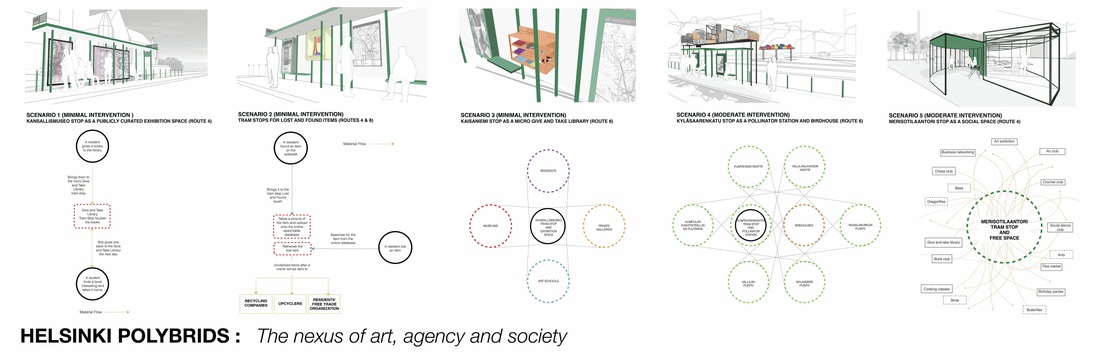

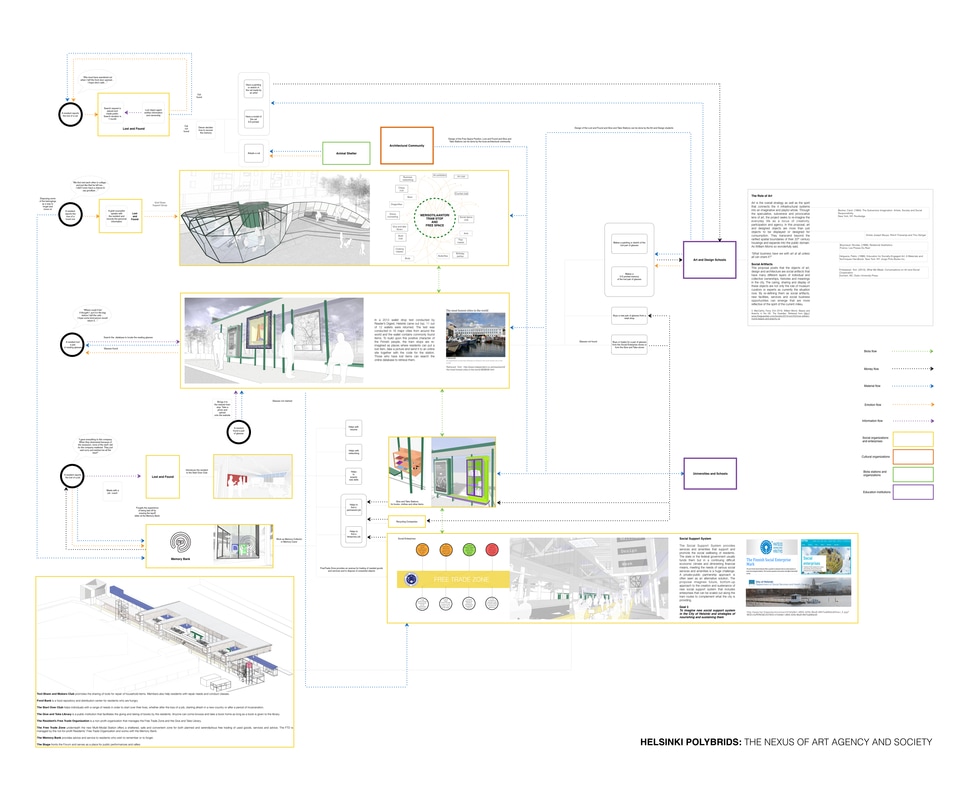

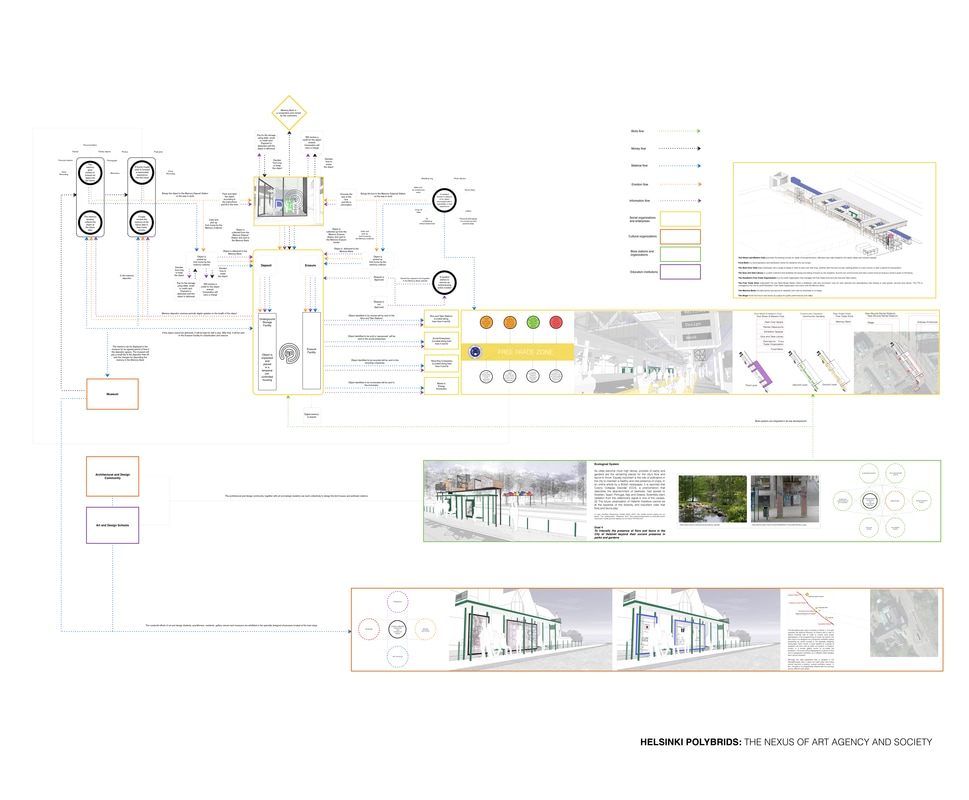

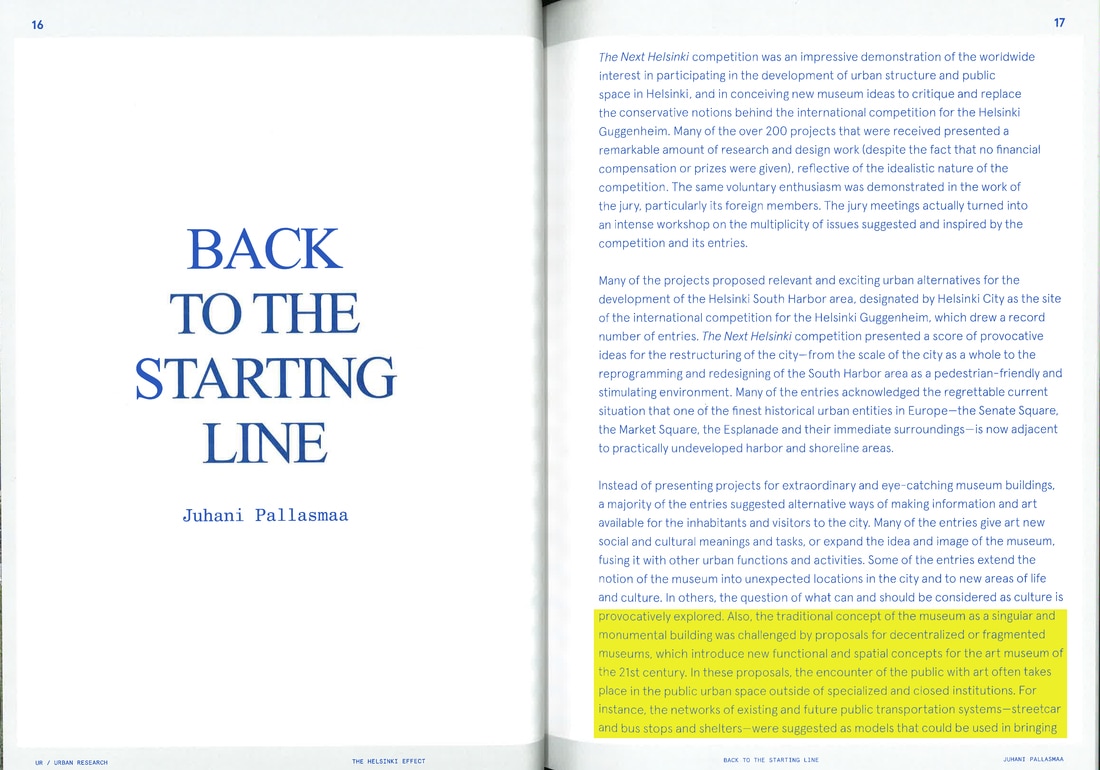

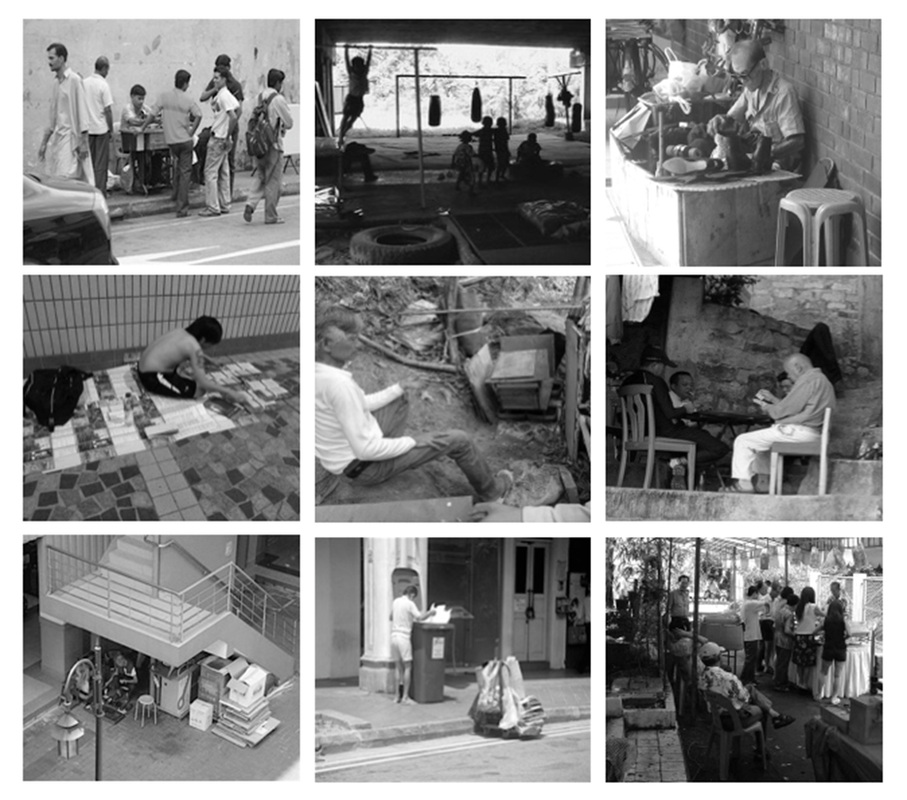

"Helsinki Polybrids: Nexus of Art, Agency and Society" has been recognized by the jury panel of the Next Helsinki international architectural competition chaired by Michael Sorkin. Among the jury members are Juhani Pallasmaa, Walter Hood, Sharon Zukin and Mabel Wilson. There were over 200 entries from 40 countries. ”Almost like a dictionary of human thought and collective imagination.” (Free quote from jury member Juhani Pallasmaa) https://www.facebook.com/TheNextHelsinki 'Almost everything in the world today is mobile. Why should art be static?' Juhani Pallasmaa #NextHelsinki https://twitter.com/CheckpointHki https://homes.yahoo.com/news/adventures-architecture-next-helsinki-adds-212325775.html http://www.nexthelsinki.org/ My shortlisted proposal and the other 200 over entries form a collective and creative counterpoint to the corporate driven art market initiative of the Guggenheim Museum. Our proposals are part of the major debate over the long term value of the Guggenheim Helsinki project, which has faced massive push backs from Finnish citizens and prompted the setting up of an alternative international architectural competition. Since the Great Recession, city officials are realizing that big, iconic projects are becoming harder to push through in parliament because citizens are demanding for greater investment in social infrastructures instead. However, to avoid financing public art is also ill-advised as it is an important contributor to the culture and economic vitality of cities. A new model of art-making, curatorial practice, presentation, support, housing and archival will need to be designed. To avoid succumbing to the seduction of another one-off piece of iconic architecture costing billions of dollars to build, exploits cheap migrant labor and requires long-term, expensive maintenance, my entry re-frames the making, curating, exhibition and sustenance of artworks as a bottom-up, community driven activity that involves a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the city. It sees economic value of art not limited to how much one can afford to pay and sell at an astronomical price later but a more socially distributive model where the ecology of production, distribution and use (and re-use) is intertwined with the everyday life of the Finnish residents. Instead of scaling up even bigger as most contemporary museums seem to suffer from these days, my entry proposes to scale-out into the different neighborhoods by borrowing the city’s existing tram lines and stops. Through the process of creating the multiple art polybrids in the city, the tram lines and stops, which serve a vast section of the Helsinki residents and are in a state of decline, get to be refurbished and renewed at the same time. This twinning of art and public infrastructure makes good economic sense. The art polybrids are also way more accessible than a singular building, and are more effective in harnessing the collective imagination and creativity of the people. Museum goers are no loner passive consumers of a paid experience. They have the power and the opportunity to co-curate, to make art and in the long run, strengthened community bonding and identity, as well as fostering a more inclusive and socially resilient society. Helsinki Polybrids: The Nexus of Art, Society and Agency is therefore designed to offer a multi-scalar, horizontally distributed, economically and socially sustainable re-framing of art, its production and experience for a 21st Nordic city. The entry was exhibited in the recently concluded Tallinn Architecture Biennale in Estonia under the Research and Development Lab, which saw 1600 visitors over 12 days. The result of the Next Helsinki Competition has also been featured in many influential architecture and design websites, and the Finnish Broadcasting Company. In 2016, the book UR: NextHelsinki by Terreform containing the short-listed entries and essays will be published to document the process and the discourse surrounding the alternative competition, which no doubt will rouse further interest and attention. Academics too, have shared their perspectives on the contentious issue. Writing on the shortlisted entries for the Next Helsinki architectural competition, Peggy Deemer (2015) wrote, “The cultural value of this competition will probably not be in the form of creative capital—although the shortlisted proposals offer excellent thinking on what makes a city work such that art can be appreciated.” (para. 9) Referring to the Next Helsinki architectural competition again, Deemer (2015) was convinced that, “its very existence as performance, display, and conversation—its cultural capital—forces the Guggenheim to scurry and scratch for its rewards.” (para. 9) Besides being in a critical moment in the global discourse to unpack, critique and contextualize the value and purpose of such lavish projects, my shortlisted entry offered an alternative model to the Guggenheim museum franchise that weaved together the art, mobility, tourism, social support and ecological systems in the city. On a professional level, my proposal is a continuation of my research on and formation of a parallel architectural practice and education model inspired by the arts. According to the Legal Information Institute (2015), the definition of the ‘the Arts’ by the United States Congress includes architecture, besides the commonly accepted artistic practices such as sculpture, painting and photography. This inclusive definition opens up the possibilities for the creative renewal of not only the architectural profession but the teaching and learning of architecture as well. The breadth and scope of design services have also increased enormously in recent decades to encompass service design, design activism and strategic design, to name a few of the new fields. The strategic design thinking and human-centered problem identification skills used by architects in their daily practice can therefore be developed and marketed as new skills-sets and services to buffer against another economic crisis. Fluid/Soundings in London and AMO in the Netherlands are excellent examples of such an interdisciplinary practice. On the other hand, the nomination of architecture collective Assemble in the U.K. for the 2105 Turner Prize in Art is a strong endorsement of design activism and the art-design nexus of contemporary spatial practice. In my conversation with a design strategist working in the multidisciplinary American architecture firm Gensler, it was very clear to her that their major clients are not only interested in just a well designed and sustainable building but also a strategic vision that aligns architecture with social and business innovations, as well as environmental stewardship. Architect Michael Sorkin, the organizer of The Next Helsinki architectural competition puts it most provocatively when he declared in an interview with the U.S. based Metropolis magazine, “We invite competition entries from any and all, includes any of the 1,700 losers from the Guggenheim competition whose work looks beyond simply building a museum on the site.” (M, Sorkin, personal communication. Jan 22, 2015). Reference Deemer, Peggy. (2015).The Guggenheim Helsinki Competition: What is the Value Proposition? Avery Review: Critical Essays on Architecture. Issue No. 9. Retrieved from http://www.averyreview.com/issues/8/the-guggenheim-helsinki-competition Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from Cornell University Law School site https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/952 Revised drawings showing the ecology of existing infrastructure, education and cultural institutions, social agencies and parks as spaces for art making, sharing, presentation and community engagement. Architect, Professor and competition judge Juhani Pallasmaa's acknowledging the Helsinki Polybrids entry in his essay, Back To The Starting Line.

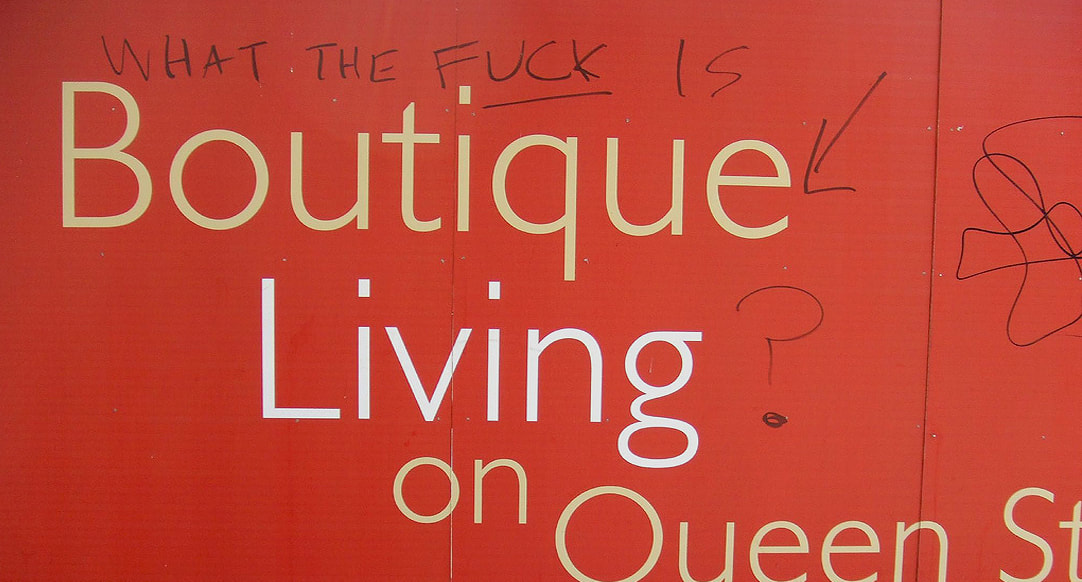

My recent work revolves around the term Lesser Urbanism. It is inspired by William Morris’s 1882 essay The Lesser Arts of Life. Lesser Urbanism curates, examines and presents aspects of urban life in high dense cities that are overlooked or ignored. Their presences are often negotiated, contested, and sustained along the margins of society. Although urban development is progressing at a relentless pace in Asia, I find there are still the vestiges of traditional rituals and local customs subsisting alongside and in quiet resistance against the process of globalization and gentrification. To disclose and celebrate these local cultures and alternative spatial practices where resourcefulness, creativity and sociability are called upon to overcome unfavorable situations and material scarcity is imperative in Asia, as more and more vernacular knowledge and places are erased and forgotten. My on-going research project on the Wah Fu informal public space in Hong Kong is one such effort. (http://www.studiochronotope.com/informal-religious-shrines-curating-community-assets-in-hong-kong-and-singapore.html). My interest in Lesser Urbanism transpires through a slow, deliberative journey reaching back to my early graduate work at Cranbrook, where I was concerned with the rules of forming and how elemental forms circumscribe space and propagates an emergent order through a bottom-up process of placement, aggregation, extension and configuration. In Lesser Urbanism, I am equally keen to articulate forms of individual and collective judgment and governance, both tacit and stated, as well as social conditions that give rise to, scale out and sustain localized spatial organizations. They herald a novel urban experience, alternative strategies of configuring spaces and make visible a vernacular poetics that are more representative of our contemporary splintered and tangled lives heightened by increasing contingency, scarcity and entropy. Urban Vessel: The New Maple Leafs Garden is a proposal that offers a new housing prototype for a congested metropolis. The vacant stadium was the home of the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team for many years. The building has been left vacant ever since the team moved to the bigger and more modern Air Canada Center. The site is bounded on three sides by high-rise apartments, a condominium and hotels. The heights of the buildings and their proximity's to the Maple Leafs Garden created a canyon like experience along Carlton Street. In the proposal, the street-level walls of the existing stadium are removed to allow the continuation of the streets into the building, and the creation of an urban foyer. Retail and commercial spaces line the four sides of the foyer. Within the original stepped profile of the stadium. dwellings are terraced towards the pool, with the roofs serving outdoor decks and private vegetable gardens. On one side of the stadium, a public urban garden is designed for both residents and public uses. The new housing typology adapted the original form of the stadium and transformed the space into a desired living environment that provides the much needed green space for residents while preserving a sense of openness in the city.

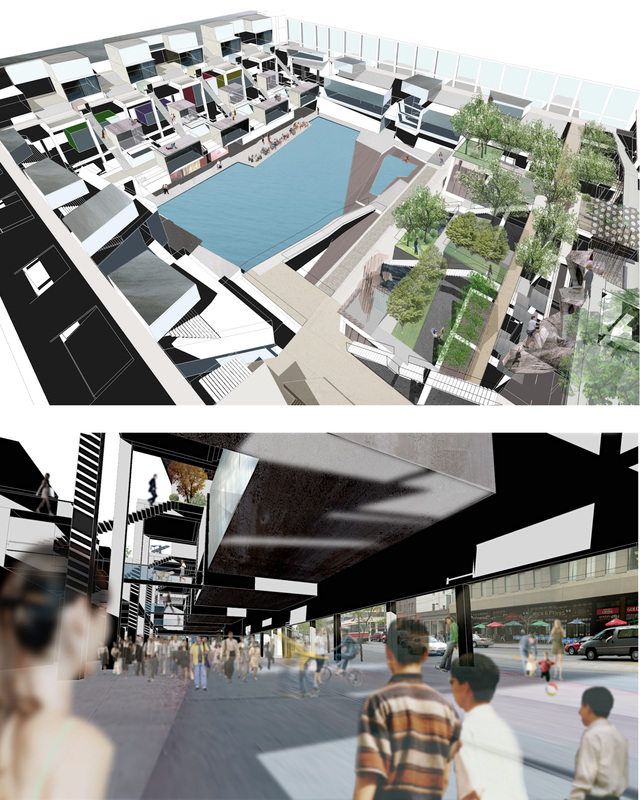

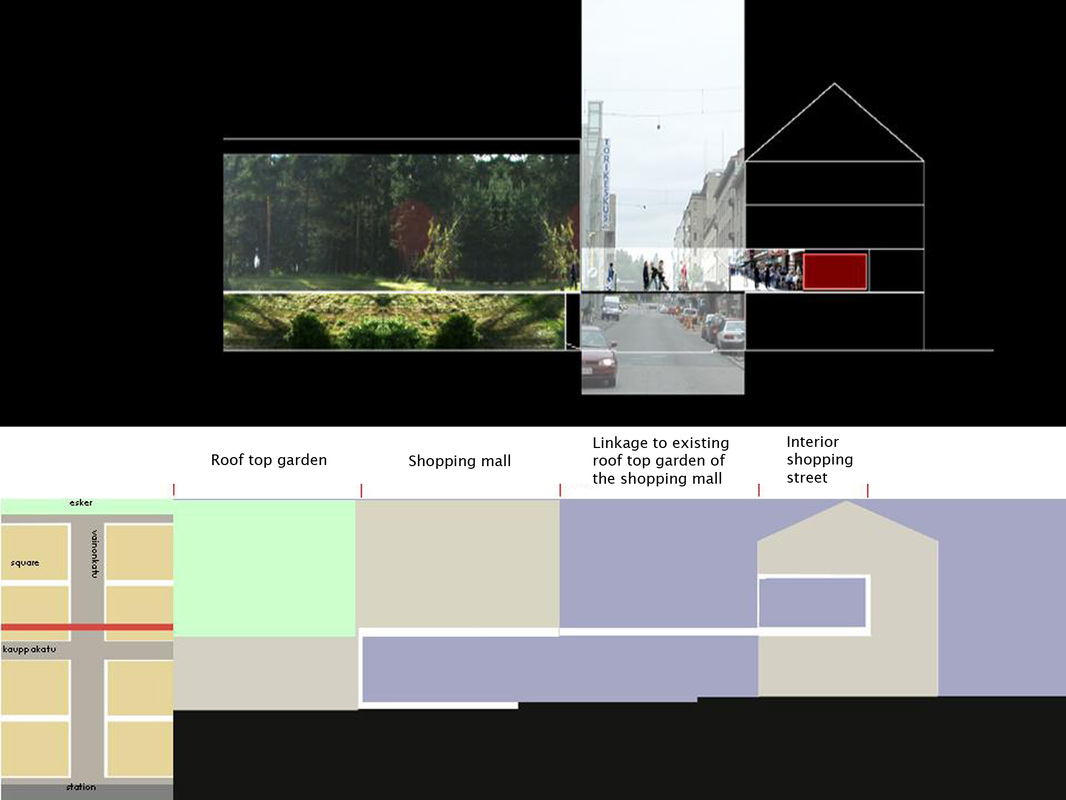

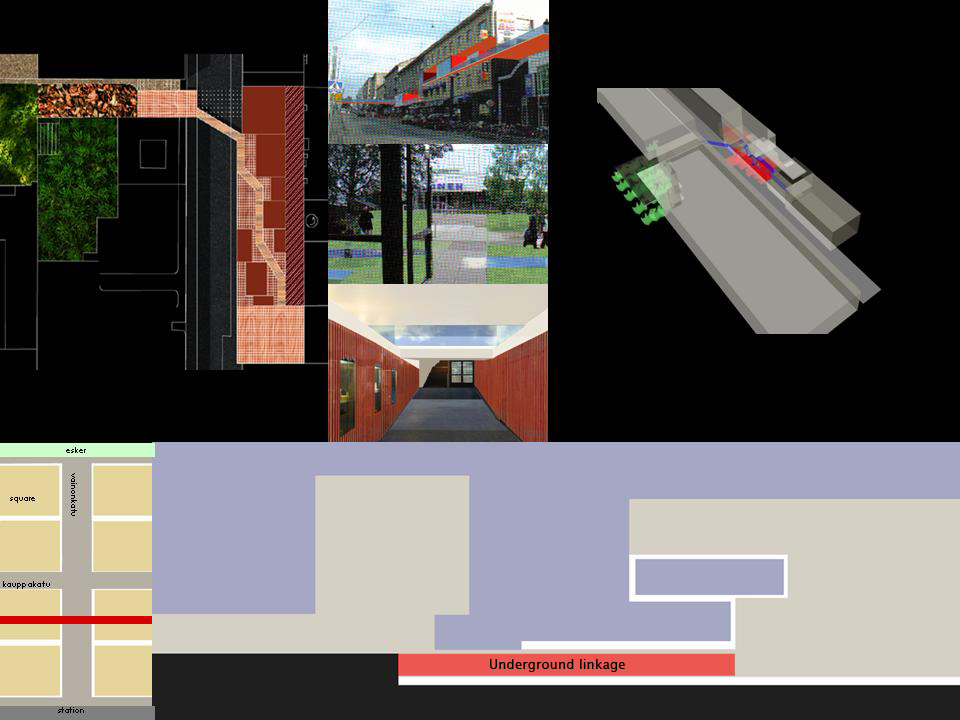

I was invited to this workshop that was held in conjunction with the Alvar Aalto Symposium in Finland. Drawing inspiration from the chest of drawers that revealed hidden gems, the alchemical vessels that formed an intriguing physical linkage to support the distillation process, and Giorgo Morandi’s watercolor renderings of everyday vessels, the goal of this collaborative proposal aimed to create multi-level spatial connections across Vainonkatu, the city’s main shopping street by linking the street, the roof garden of the Stockman store and the existing network of underground pedestrian passages. A gap on the market square’s southeast side is closed by means of a rooftop extension in the form of a new, elevated street that leads to the city’s hidden rooftop attractions.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed