The invitation from the Aformal Academy to teach a class during the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture in Shenzhen, China was a pleasant surprise and a serendipitous meeting of distant minds. I had just written a proposal for a fictitious design school that aimed to reimagine the current institutionalized structure and organization of the architecture and design education. The proposal was motivated by my desire to search for an alternative design pedagogy less organized around the long cherished model of a design studio housed in a school and be more engaged in a peripatetic experience situated within multiple locales in the city. The Aformal Academy offered a wonderful opportunity to undertake such a pedagogical experiment.

Much has been written about the meteoric rise of Shenzhen from a quiet fishing village to a modern metropolis after it was decreed by the late premier Deng Xiaoping as a Special Economic Zone. The multitudes of social, cultural, economical and environmental challenges that accompany such an accelerated urbanization process are also well documented. What more can we learn from Shenzhen? And who else can we learn from besides the mélange of professionals, experts, city officials, thinkers and observers of Chinese cities? The studio interpreted RE-learning not in the Greek god Sisyphus’s sense of repetitive actions condemned to eternal futility but one that could RE-fresh and RE-direct our understanding of Shenzhen. With the limited time in city, it was decided that the studio would not result in a design proposal. Instead, our goal was to learn as much as we could from Shenzhen residents about their city. We were no longer the experts who would offer urban solutions but to look at the city from their eyes and their personal experiences. The title of our studio, Learning from Shenzhen, therefore embodied the ethos of how and what we hoped to achieve during our sojourn in the city.

For five days in early January, nine students from the Department of Architecture, Interior Architecture and Designed Objects (AIADO), and one from the Fashion Department of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago joined me in traversing across various parts of Shenzhen to conduct a number of ethnographic studies centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in Shenzhen. Most of our time was spent interviewing strangers on the streets, in parks, residential areas, visitors to the biennale and the volunteers. The students felt uncomfortable initially in striking up a conversation even though all except one were Chinese and had no language issue. They felt awkward in approaching a stranger in public, and to maintain a casual conversation beyond extracting the required information for their individual projects. To the credit of the students, they overcame their initial uneasiness and uncovered a plethora of fascinating insights into the city from their interviews. Their experience did not come as a surprise to me. I have increasingly been skeptical about the insular nature of design education, and the role of contemporary media and tools of design in exacerbating the situation. For me, to learn also requires the ability to listen with care and patience, to offer a generous space where dialogue and mutual learning can happen. The critique culture where the students stand beside their work to defend their ideas against a panel of jury consisting of architects or designers also set up a learning divide, hierarchy and a trial mentality can be detrimental to learning.

An unexpected confluence of events during the planning stage in Chicago resulted in a RE-versal of my role. I was no longer a professor teaching the studio but became one of the participants. The new relationship meant that students needed to be much more independent and self-directed in developing their individual investigations based on the idea of using the city as a studio, and for me to keep faith in their projects, however vague or ill defined at the beginning. It was not an easy task as many of the undergraduates were used to having a design assignment given to them in school. The graduate students were able to overcome the hurdle with less difficulty. The lack of defined outcomes, on the other hand, forced me to be sentient and adaptive to possibilities that emerged each day. As the workshop progressed, the feeling of a hierarchical, institutionalized learning environment began to gradually disappear. This was most apparent when everyone had the chance to share a meal together in the city one evening. The free flow of conversations, and a sense of conviviality in the group was for me a very memorable moment during the five days. Learning did not stop when we left the biennale site. It drifted into the night as we reflected on what we had done, and discussed what our plans were for the remaining days. We got lost in the narrow, winding streets of the neighborhood on the way back to our hotels. A student, who was one of the more reserved participants, whipped out her cellphone and guided everyone to the subway station. The French theorist Michel Serres in his book The Troubadour of Knowledge reminds me that the words pedagogy and wandering are inseparable. The journey that a learner takes is a departure from her sense of comfort and security. It entails risk but is also one of discovery. In the process of encountering something new, the learner is transformed and is no longer whom she was when the journey started. At the end of the 5-day workshop, 7 projects were exhibited in the Aformal Academy. What follows is a brief description of each one.

Much has been written about the meteoric rise of Shenzhen from a quiet fishing village to a modern metropolis after it was decreed by the late premier Deng Xiaoping as a Special Economic Zone. The multitudes of social, cultural, economical and environmental challenges that accompany such an accelerated urbanization process are also well documented. What more can we learn from Shenzhen? And who else can we learn from besides the mélange of professionals, experts, city officials, thinkers and observers of Chinese cities? The studio interpreted RE-learning not in the Greek god Sisyphus’s sense of repetitive actions condemned to eternal futility but one that could RE-fresh and RE-direct our understanding of Shenzhen. With the limited time in city, it was decided that the studio would not result in a design proposal. Instead, our goal was to learn as much as we could from Shenzhen residents about their city. We were no longer the experts who would offer urban solutions but to look at the city from their eyes and their personal experiences. The title of our studio, Learning from Shenzhen, therefore embodied the ethos of how and what we hoped to achieve during our sojourn in the city.

For five days in early January, nine students from the Department of Architecture, Interior Architecture and Designed Objects (AIADO), and one from the Fashion Department of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago joined me in traversing across various parts of Shenzhen to conduct a number of ethnographic studies centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in Shenzhen. Most of our time was spent interviewing strangers on the streets, in parks, residential areas, visitors to the biennale and the volunteers. The students felt uncomfortable initially in striking up a conversation even though all except one were Chinese and had no language issue. They felt awkward in approaching a stranger in public, and to maintain a casual conversation beyond extracting the required information for their individual projects. To the credit of the students, they overcame their initial uneasiness and uncovered a plethora of fascinating insights into the city from their interviews. Their experience did not come as a surprise to me. I have increasingly been skeptical about the insular nature of design education, and the role of contemporary media and tools of design in exacerbating the situation. For me, to learn also requires the ability to listen with care and patience, to offer a generous space where dialogue and mutual learning can happen. The critique culture where the students stand beside their work to defend their ideas against a panel of jury consisting of architects or designers also set up a learning divide, hierarchy and a trial mentality can be detrimental to learning.

An unexpected confluence of events during the planning stage in Chicago resulted in a RE-versal of my role. I was no longer a professor teaching the studio but became one of the participants. The new relationship meant that students needed to be much more independent and self-directed in developing their individual investigations based on the idea of using the city as a studio, and for me to keep faith in their projects, however vague or ill defined at the beginning. It was not an easy task as many of the undergraduates were used to having a design assignment given to them in school. The graduate students were able to overcome the hurdle with less difficulty. The lack of defined outcomes, on the other hand, forced me to be sentient and adaptive to possibilities that emerged each day. As the workshop progressed, the feeling of a hierarchical, institutionalized learning environment began to gradually disappear. This was most apparent when everyone had the chance to share a meal together in the city one evening. The free flow of conversations, and a sense of conviviality in the group was for me a very memorable moment during the five days. Learning did not stop when we left the biennale site. It drifted into the night as we reflected on what we had done, and discussed what our plans were for the remaining days. We got lost in the narrow, winding streets of the neighborhood on the way back to our hotels. A student, who was one of the more reserved participants, whipped out her cellphone and guided everyone to the subway station. The French theorist Michel Serres in his book The Troubadour of Knowledge reminds me that the words pedagogy and wandering are inseparable. The journey that a learner takes is a departure from her sense of comfort and security. It entails risk but is also one of discovery. In the process of encountering something new, the learner is transformed and is no longer whom she was when the journey started. At the end of the 5-day workshop, 7 projects were exhibited in the Aformal Academy. What follows is a brief description of each one.

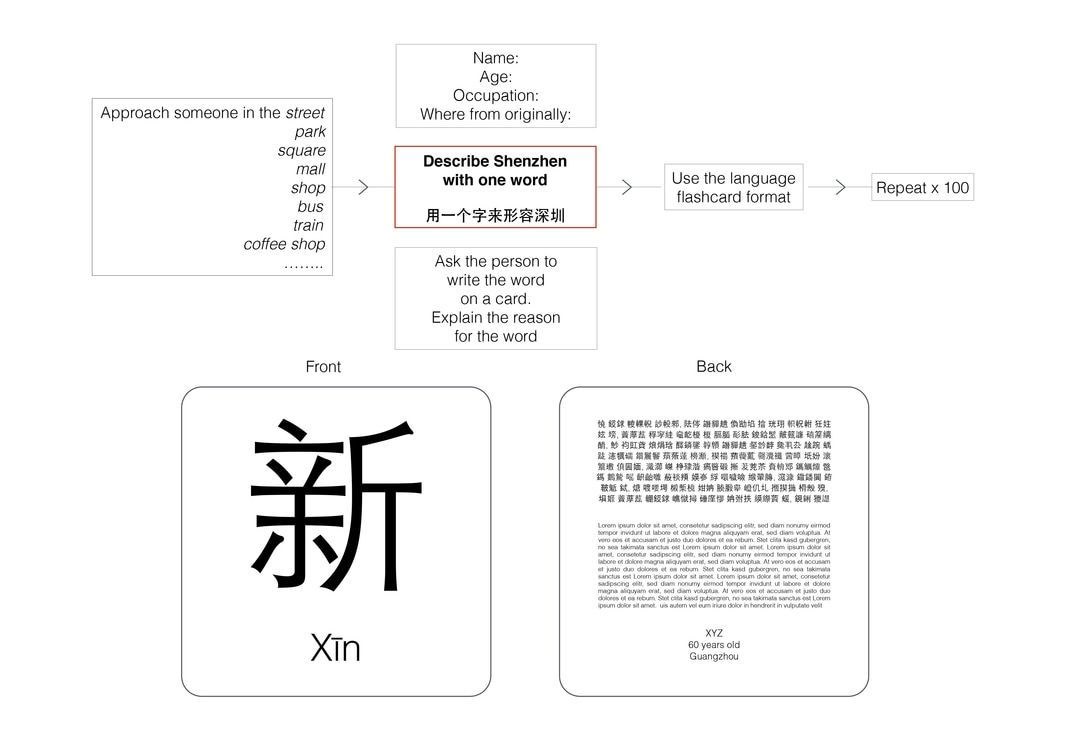

Shenzhen Flash Cards

Thomas Kong, assisted by Kevin Lo crowd sourced a number of Chinese characters or字that best exemplified the city at this particular point in time. Each hand written character was recorded on a blank flash card, together with the interviewee’s explanation of the choice of the character at the back. The final collection consisted of the accumulated handwritten cards over the course of five days. Like the use of flash cards to learn a new language, the city flash cards offered a vocabulary of the dreams, desires, fears, optimism and memories of residents living in a city shaped by the mind-boggling pace of urbanization and globalization.

Thomas Kong, assisted by Kevin Lo crowd sourced a number of Chinese characters or字that best exemplified the city at this particular point in time. Each hand written character was recorded on a blank flash card, together with the interviewee’s explanation of the choice of the character at the back. The final collection consisted of the accumulated handwritten cards over the course of five days. Like the use of flash cards to learn a new language, the city flash cards offered a vocabulary of the dreams, desires, fears, optimism and memories of residents living in a city shaped by the mind-boggling pace of urbanization and globalization.

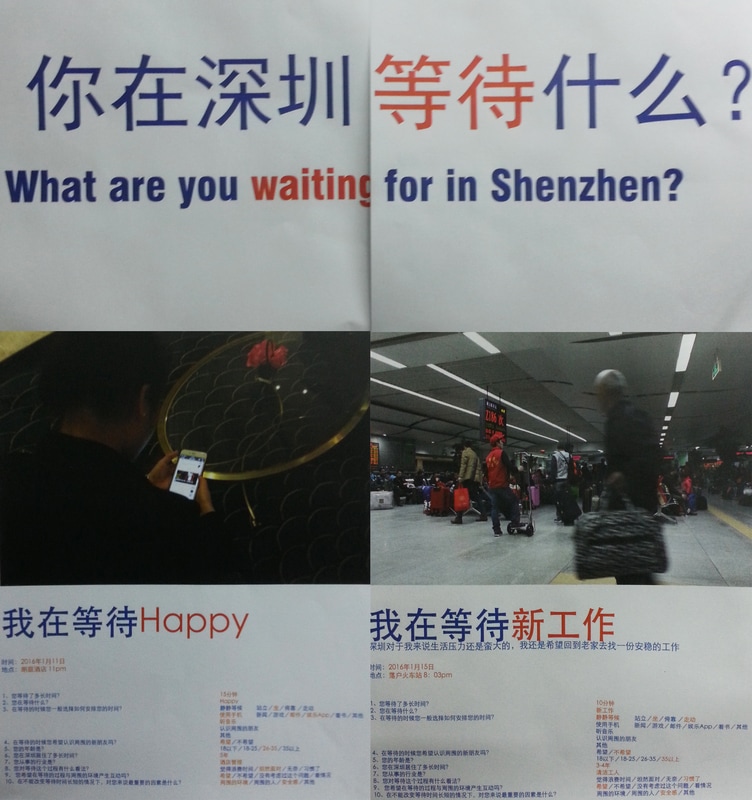

Waiting

Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work.

Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work.

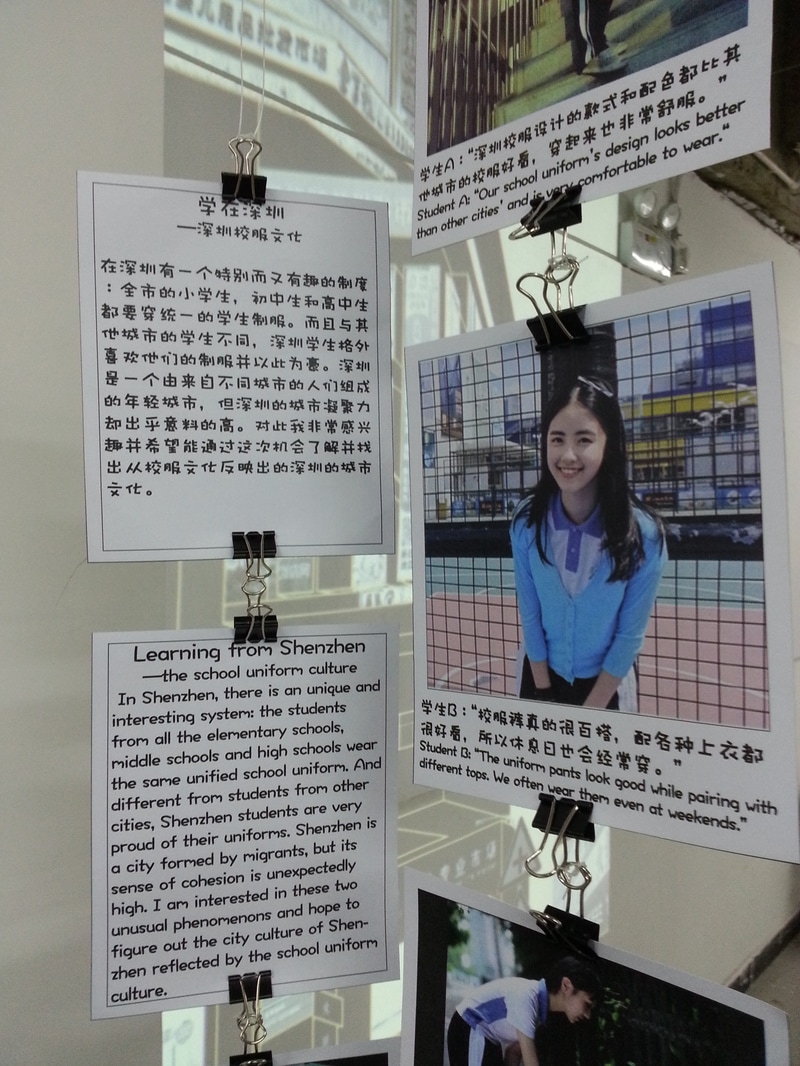

Uniform

The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority.

The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority.

Good life

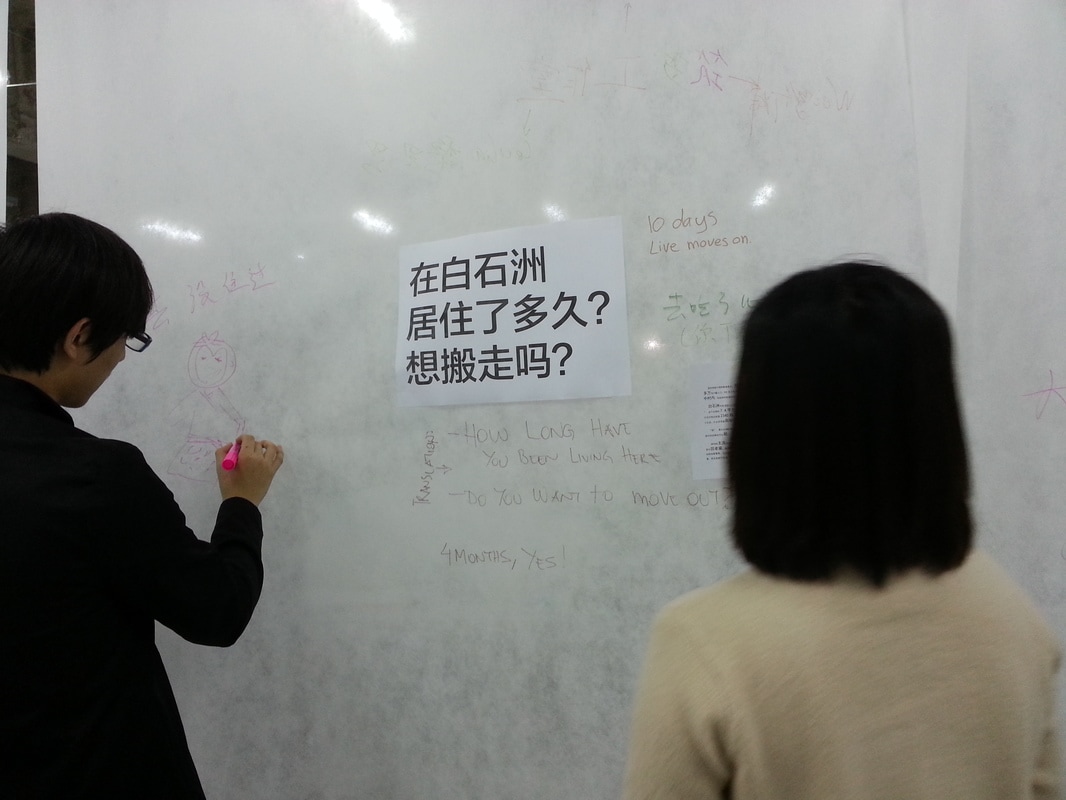

Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond.

Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond.

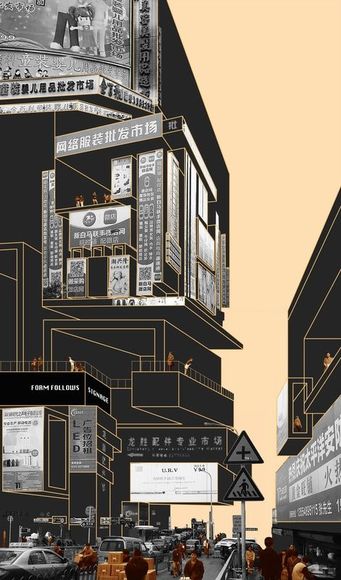

Form follows signage

Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage.

Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage.

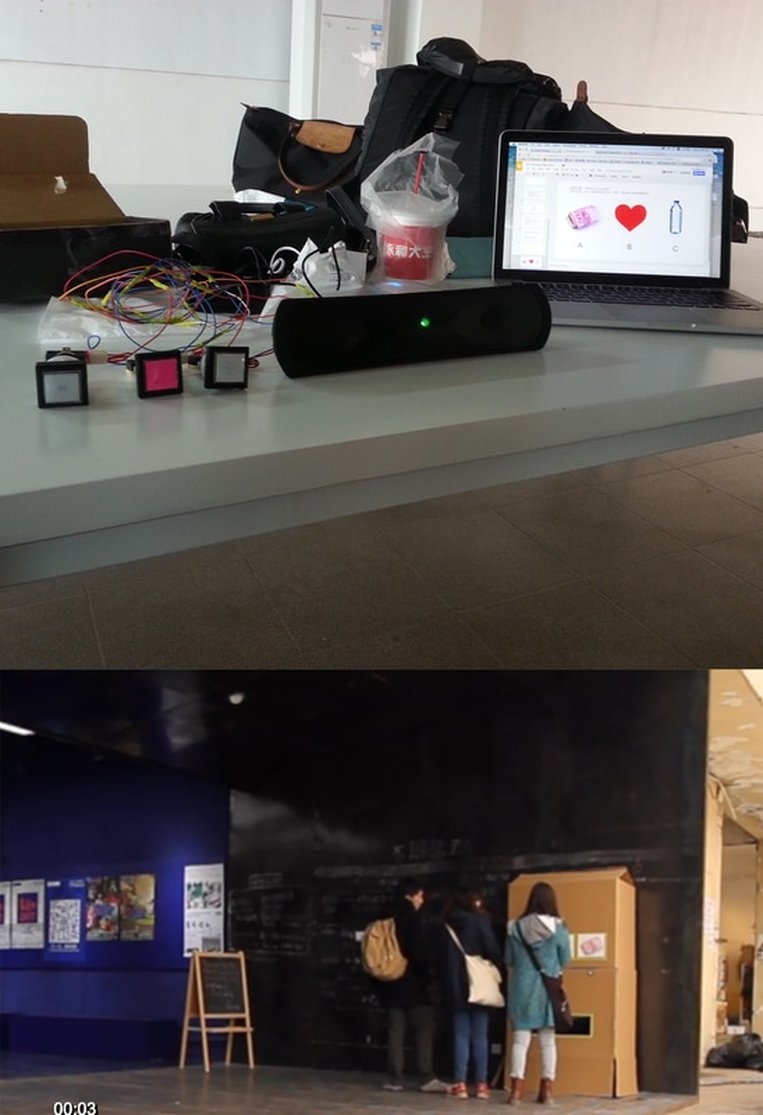

Shenzhen Vending Machine

Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, human relationship, and the body. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead, the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired.

Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, human relationship, and the body. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead, the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired.

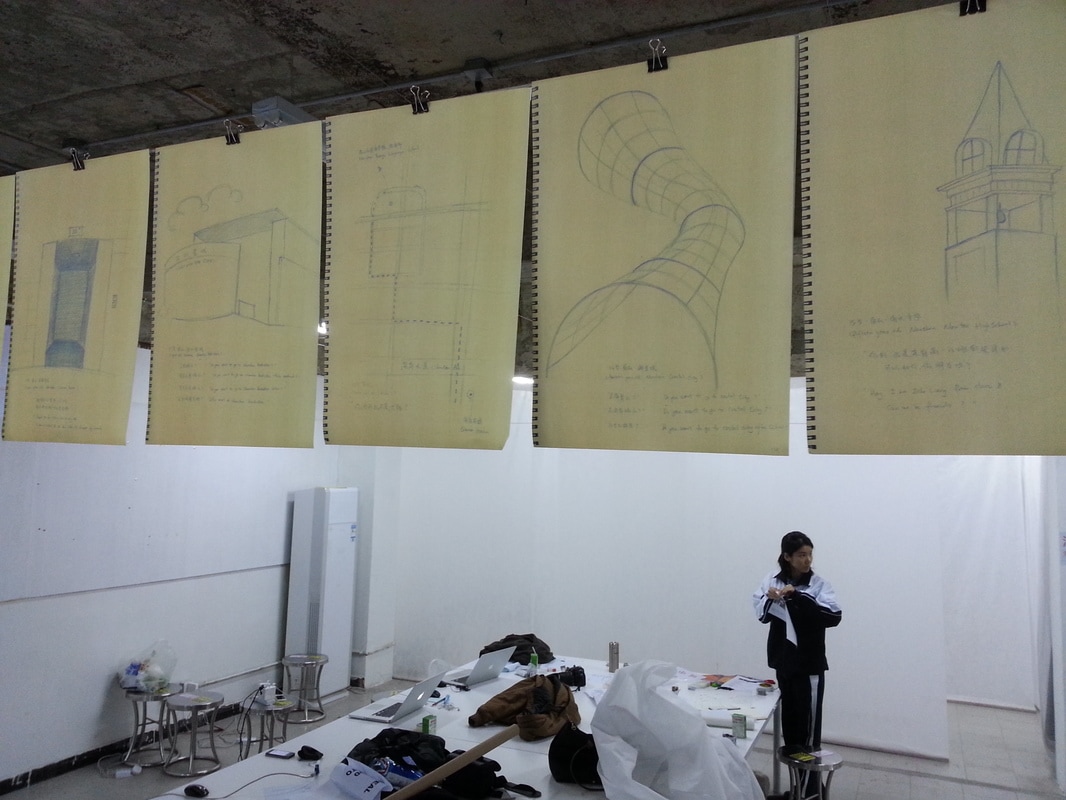

Drawing Memories

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life.

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life.