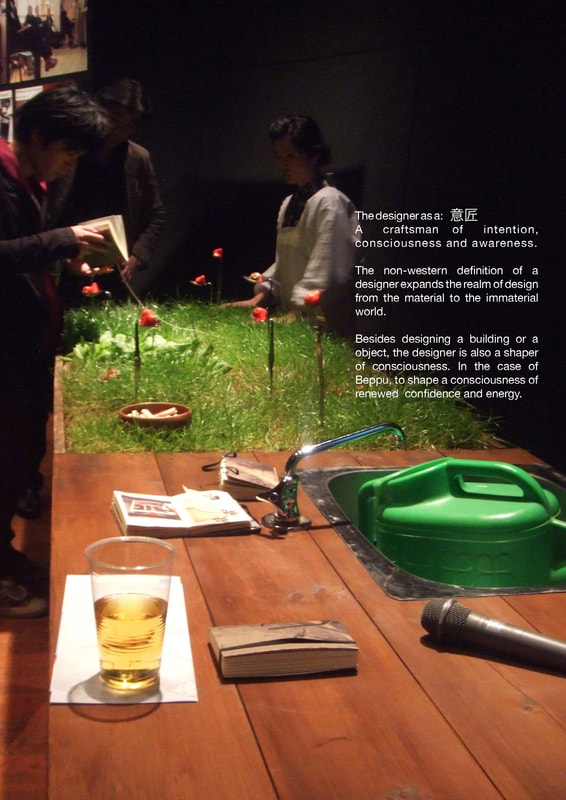

The Beppu Street Studio and ZERO project were instrumental in re-shaping my own thinking and practice as an architect. Working with a diverse group of people from different backgrounds opened my eyes to the value of stakeholder engagement, the importance of listening, careful and critical observation, and be empathetic to different voices. Through one of the many late night conversations with my Japanese collaborators, I developed the concept of the designer as a 意匠 (Yìjiàng). The character 意, carries multiple meanings- as consciousness, meaning, intention, significance, idea, sense, desire, thought and longing. As 意匠, a designer is a craftsperson who shapes our consciousness and produces meaning. Through the designer’s work, our sense of the world is heightened, and the quotidian elevated to a level of significance. A designer also shapes our desires and longings. Our yearnings for homeland, justice, freedom or luxury are given material form. 意 is made up of several ideograms- {sound (⾳ Ying)}, {heart (⼼ Xing)}, {stand, establish or set (⽴ Li)}, and {day, daily or sun (⽇ Re)}. On the other hand, 匠 or craftsperson consists of ⼕ (Fang), which means a box, and ⽄ (Jin), which is an ax. The combinatory meanings of 意匠, from the elemental to the extended meanings offer a much more expanded role that a designer can take in contemporary society. First and foremost, a designer needs to be attentive to sound (音 Ying) in the design process. It refutes the primacy of the visual, especially when the design process is much more screen-based now. By being attentive to sound, I come to understand that the voices from stakeholders, users and the unrepresented members of society need to be heard as well in the design process. From (⼼ Xing), we know passion, generosity, emotion, and empathy are as important as skills and techniques, while (⽴ Li) suggests that design is a setting in place, whether the outcome is a piece of furniture, a book, or a strategy. (⽇Re) reminds us that as a designer, we need daily devotion and a dedication to the continuing refinement and learning of our craft. Our tools, ⽄(Jin) are housed in a box that affords mobility.

The concept of 意匠 underpins many of my works. It serves as a platform and opens up opportunities for engagement beyond the design of a building. It allows me to bring awareness to an urgent issue using non-architectural tools. It reminds me that intentionality can take material or immaterial form. As 意匠, I have a sense of freedom and openness that provides me with different perspectives on a problem and the possible range of solutions besides a building. It cultivates an interdisciplinary mind that is critical to addressing today’s complex problems. Interestingly, 意匠 means “Designer” in the Japanese language while in simplified Chinese, it is “Artist”. At the heart of 意匠 lies the art-design nexus.

The concept of 意匠 underpins many of my works. It serves as a platform and opens up opportunities for engagement beyond the design of a building. It allows me to bring awareness to an urgent issue using non-architectural tools. It reminds me that intentionality can take material or immaterial form. As 意匠, I have a sense of freedom and openness that provides me with different perspectives on a problem and the possible range of solutions besides a building. It cultivates an interdisciplinary mind that is critical to addressing today’s complex problems. Interestingly, 意匠 means “Designer” in the Japanese language while in simplified Chinese, it is “Artist”. At the heart of 意匠 lies the art-design nexus.