Abstract

Taking Singapore as a laboratory for thinking and designing future healthcare spaces, services, and deliveries, architecture, and industrial design students worked together to develop innovative and scalable solutions for a distributed healthcare system in the year 2030. The projects are collaborative, multi-scalar, and multi-stakeholder in approach. They considered near-to-far-future scenarios for a distributed system across different sites, touchpoints, and experiences by harnessing digital technologies, deploying connected care platforms, and being supported by grassroots organizations, social agencies, and communities. The paper will share the critical reflections and outcomes from the studio led by an architect, experience, and industrial designers working in academia and the industry. The paper argues that designing a system-based healthcare future demands a retooling of current architecture education to one that is multidisciplinary, collaborative, and empathetic.

Introduction

In January 2021, the Department of Architecture and Division of Industrial Design of the National University of Singapore, together with Philips ASEAN Pacific Centre Singapore (APAC), jointly ran a design studio focusing on the future of the city-state’s healthcare system. Titled Healthcare 2030, the design studio tutors consisting of an architect, an industrial designer, and an experience designer co-conceived the design brief that encouraged architecture and industrial design students to develop innovative and scalable solutions for a distributed healthcare system in 2030. Working collaboratively in teams, students came up with multi-scalar projects comprising of multi-stakeholders and researched changing societal behaviours, cultural norms, and accessibility. They considered near-to-far-future scenarios for a distributed system at different sites, touchpoints, and experiences by harnessing digital technologies, deploying connected care platforms, and supported by grassroots organizations, social agencies, and communities. Through critical reflections on the design studio and the student projects, the paper argues that designing a system-based healthcare future demands a retooling of current architecture education to one that is multidisciplinary, collaborative, and empathetic.

Overview of Architectural Education

Architectural education occupies a unique place among other professional programmes in a university. Situated at the intersection of different fields and disciplines, learning to design a building requires the student to synthesise different knowledge, information, and skills to have a coherent concept, design process, and outcome. Central to architectural education is the design studio, and public critique as the primary mode of feedback. They form the cornerstone of teaching and learning in the curriculum. Over the years, architect-educators and academics have critically examined the curriculum and offered ideas for its reform (Dutton 1987; Boyer E, Mitgang L 1996; Buchanan 2012; Nicol and Pilling 2000; ARB 2021). Architectural education is set up to primarily support individual development. The studio professor's view and architectural expertise drive the design studio's focus. Not surprisingly, invited critics often share similar opinions and knowledge about architecture. Collaboration, if it happens, takes place among peers in the studio. Given the demands of imparting different skills and knowledge, the perception among faculty is that there is never enough time to adequately prepare a student for the profession. Increasing administrative responsibilities, curricular structures of different disciplines, timetables, and assessment criteria all impede collaborative teaching and learning that leads to a monoculture of thinking and making of architecture.

On the other hand, an overly formalistic or technical approach to architectural design can pose concerns. First, questions of form or technology usually take precedence over the primary goal of designing for people. Seldom does an architectural conversation revolve around the future occupants of the building. And if they do, the abstract, universal and generic notion of the user becomes a poor substitute. It lacks the full complexities of the human experience and the range of emotions that an actual client or user can offer. Second, a building does not exist in isolation. It is part of a larger, complex system consisting of the social, political, cultural, ecological, economic, and technological contexts. Objects, buildings, and cities are progressively digitally networked to produce new experiences that enable seamless connectivity, performance, and service delivery. Current architectural curriculum rarely addresses the interconnected experiences of crossing muti-scalar realms, which the convergence of the material, digital, human, and natural worlds calls for.

Re-tooling the Design Studio Experience

The Healthcare 2030 design studio differed from the previous studios at the National University of Singapore's Department of Architecture. It focused on the trinity of people, spaces, and services in forming a continuous, interconnected experiential journey. The design brief, schedule, and assignments were co-designed collectively. Over several Zoom meetings, the studio tutors decided that students needed to think and design systematically and across different scales, touchpoints, and empathise with the pain points of the patients and healthcare providers. The choice of transit, home, community, and healthcare facilities provided the contexts for their designs. On the other hand, Discover, Frame, Ideate, and Build divided the thirteen-week semester into four key phases. During the Discover phase, four teams (two architecture and two industrial design students) carried out contextual research based on a selected illness. Each team researched the behavioural, emotional, cultural, social, and economic contexts of the patient and the illness through observations, interviews, and literature reviews. The Framing phase called for identifying opportunities through insights gained from the Discover phase. The multidisciplinary teams co-created broad frameworks to organise their approaches and collectively discussed the possible sites that best showcased their designs. Each team also came up with a What If? question. It was the driving provocation, aspiration, and a call for imagination in designing new solutions. For example, What if Every Neighbourhood Could be Dementia-Friendly? For the Ideation phase, experience designers from Philips APAC conducted a one-day workshop to help the teams to visualise the entire experience journey for the patients, caregivers and healthcare providers.

Taking Singapore as a laboratory for thinking and designing future healthcare spaces, services, and deliveries, architecture, and industrial design students worked together to develop innovative and scalable solutions for a distributed healthcare system in the year 2030. The projects are collaborative, multi-scalar, and multi-stakeholder in approach. They considered near-to-far-future scenarios for a distributed system across different sites, touchpoints, and experiences by harnessing digital technologies, deploying connected care platforms, and being supported by grassroots organizations, social agencies, and communities. The paper will share the critical reflections and outcomes from the studio led by an architect, experience, and industrial designers working in academia and the industry. The paper argues that designing a system-based healthcare future demands a retooling of current architecture education to one that is multidisciplinary, collaborative, and empathetic.

Introduction

In January 2021, the Department of Architecture and Division of Industrial Design of the National University of Singapore, together with Philips ASEAN Pacific Centre Singapore (APAC), jointly ran a design studio focusing on the future of the city-state’s healthcare system. Titled Healthcare 2030, the design studio tutors consisting of an architect, an industrial designer, and an experience designer co-conceived the design brief that encouraged architecture and industrial design students to develop innovative and scalable solutions for a distributed healthcare system in 2030. Working collaboratively in teams, students came up with multi-scalar projects comprising of multi-stakeholders and researched changing societal behaviours, cultural norms, and accessibility. They considered near-to-far-future scenarios for a distributed system at different sites, touchpoints, and experiences by harnessing digital technologies, deploying connected care platforms, and supported by grassroots organizations, social agencies, and communities. Through critical reflections on the design studio and the student projects, the paper argues that designing a system-based healthcare future demands a retooling of current architecture education to one that is multidisciplinary, collaborative, and empathetic.

Overview of Architectural Education

Architectural education occupies a unique place among other professional programmes in a university. Situated at the intersection of different fields and disciplines, learning to design a building requires the student to synthesise different knowledge, information, and skills to have a coherent concept, design process, and outcome. Central to architectural education is the design studio, and public critique as the primary mode of feedback. They form the cornerstone of teaching and learning in the curriculum. Over the years, architect-educators and academics have critically examined the curriculum and offered ideas for its reform (Dutton 1987; Boyer E, Mitgang L 1996; Buchanan 2012; Nicol and Pilling 2000; ARB 2021). Architectural education is set up to primarily support individual development. The studio professor's view and architectural expertise drive the design studio's focus. Not surprisingly, invited critics often share similar opinions and knowledge about architecture. Collaboration, if it happens, takes place among peers in the studio. Given the demands of imparting different skills and knowledge, the perception among faculty is that there is never enough time to adequately prepare a student for the profession. Increasing administrative responsibilities, curricular structures of different disciplines, timetables, and assessment criteria all impede collaborative teaching and learning that leads to a monoculture of thinking and making of architecture.

On the other hand, an overly formalistic or technical approach to architectural design can pose concerns. First, questions of form or technology usually take precedence over the primary goal of designing for people. Seldom does an architectural conversation revolve around the future occupants of the building. And if they do, the abstract, universal and generic notion of the user becomes a poor substitute. It lacks the full complexities of the human experience and the range of emotions that an actual client or user can offer. Second, a building does not exist in isolation. It is part of a larger, complex system consisting of the social, political, cultural, ecological, economic, and technological contexts. Objects, buildings, and cities are progressively digitally networked to produce new experiences that enable seamless connectivity, performance, and service delivery. Current architectural curriculum rarely addresses the interconnected experiences of crossing muti-scalar realms, which the convergence of the material, digital, human, and natural worlds calls for.

Re-tooling the Design Studio Experience

The Healthcare 2030 design studio differed from the previous studios at the National University of Singapore's Department of Architecture. It focused on the trinity of people, spaces, and services in forming a continuous, interconnected experiential journey. The design brief, schedule, and assignments were co-designed collectively. Over several Zoom meetings, the studio tutors decided that students needed to think and design systematically and across different scales, touchpoints, and empathise with the pain points of the patients and healthcare providers. The choice of transit, home, community, and healthcare facilities provided the contexts for their designs. On the other hand, Discover, Frame, Ideate, and Build divided the thirteen-week semester into four key phases. During the Discover phase, four teams (two architecture and two industrial design students) carried out contextual research based on a selected illness. Each team researched the behavioural, emotional, cultural, social, and economic contexts of the patient and the illness through observations, interviews, and literature reviews. The Framing phase called for identifying opportunities through insights gained from the Discover phase. The multidisciplinary teams co-created broad frameworks to organise their approaches and collectively discussed the possible sites that best showcased their designs. Each team also came up with a What If? question. It was the driving provocation, aspiration, and a call for imagination in designing new solutions. For example, What if Every Neighbourhood Could be Dementia-Friendly? For the Ideation phase, experience designers from Philips APAC conducted a one-day workshop to help the teams to visualise the entire experience journey for the patients, caregivers and healthcare providers.

Fig 1. Architecture and industrial design students mapping the experience journeys of the patients, caregivers and healthcare providers at the Philips APC studio.

Finally, in the Build phase, students planned how to communicate their research and designs in the most visually compelling way. The teams pulled their respective knowledge and skills to deliver an integrated and cohesive final presentation. The industrial design students made videos of the patient's experience journey in the new distributed healthcare system and prototypes of the devices. On the other hand, the architecture students depicted the redesigned site, new building/s, and interior spaces in large-scale prints. Each student was responsible for a part of the verbal presentation, and everyone contributed to the question and answer portion of the final review. As mentioned earlier in the essay, architectural reviews are often insular. In the worst-case scenario, it is a means to reaffirm the professor's ideology. It can also become confrontational, which does not help the student to learn. In the case of the Healthcare 2030 studio, it was a platform for sharing, learning, and advancing good practices and knowledge in the field of healthcare design. Guests and students had only one common goal: how could we collectively design better spaces, services, and experiences for patients inflicted by the illnesses? In the following sections, the paper will introduce three projects that are emblematic of the re-tooled design studio experience where place and user-centric, as well as multi-scalar designs for a distributed healthcare system is integrated with technologies for the monitoring, caring, and healing process.

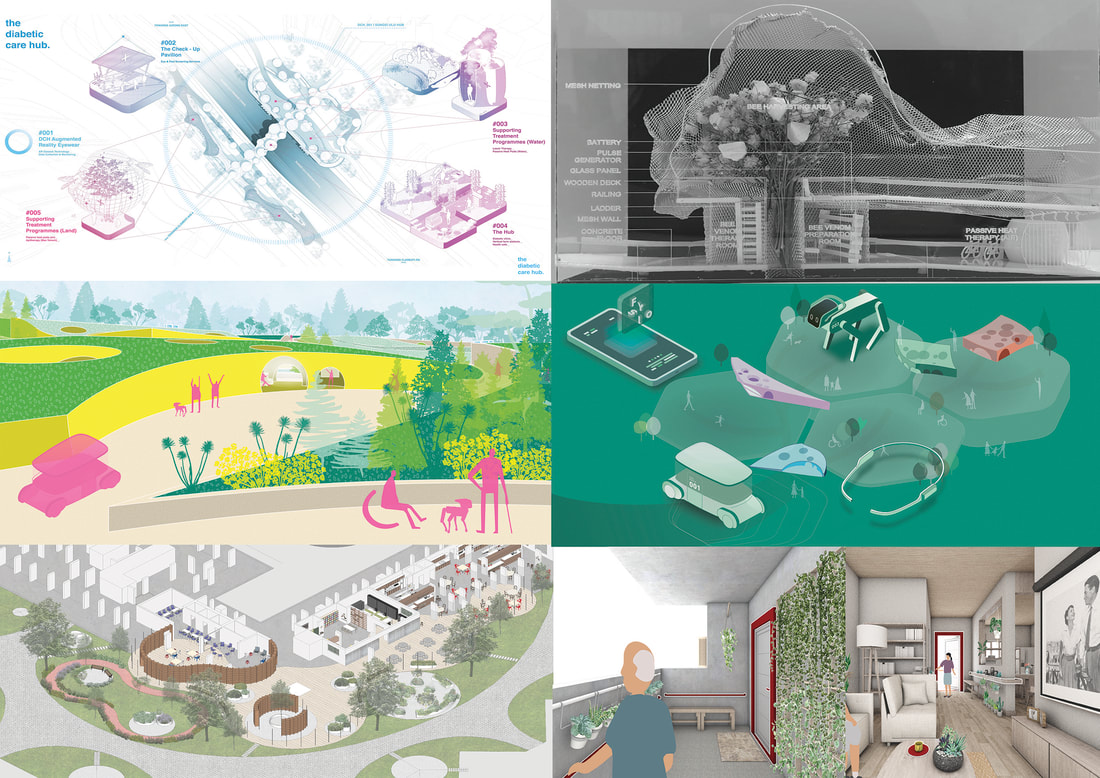

Fig 2. Top; Diabetes Care Hub. Middle: Fysio. Bottom: Forget Us Not.

Healthcare in Singapore

Singapore's healthcare system is ranked high in the world (Statista, 2021; Bloomberg, 2014; Straits Times, 2014). The government makes efforts to ensure that healthcare remains affordable and accessible through financial subsidies, incentives to keep a healthy lifestyle, technological innovations, and careful management of costs. However, like many other countries, Singapore's healthcare system faces challenges on multiple fronts, such as an ageing population, the charge of chronic diseases like diabetes, workforce shortage, and rising costs. In 2012, the Ministry of Health set up a task force to develop a Healthy Living Master Plan (MOH, 2014; Kok, 2014). Based on feedback from Singaporeans, the task force identified the importance of a well-designed environment conducive to healthy living, that a healthy lifestyle excludes no one, and keeping costs affordable. Place, People, and Price were identified as driving forces to promote healthy living as a way of life.

For Place, the master plan envisaged a future where healthcare facilities and services will be close to and connected to parks, live and work spaces for better accessibility and seamless integration. To create a more physically inclusive environment and to encourage walking and cycling, universal and active design strategies were recommended. The Land Transport Authority is currently building an island-wide network of walkways to shelter commuters from inclement weather and encourage walking to the bus and train stations. On the other hand, residents could locate public exercise facilities and find activity programmes within two hundred metres of their homes through their mobile phones. For People, the master plan strived to promote mass participation in outdoor activities with rewards for achieving a personal target, attending health talks, and consuming healthy food. Equally important, the master plan aimed to harness the social energy of the community and sought to empower groups and individuals by training neighbourhood ambassadors and community coaches to assist professional healthcare workers. For Price, the government introduced several schemes to help low-income families and individuals access medical services. Food and beverage providers were also encouraged through incentives to offer healthier ingredients and affordable food options. As residents eat out often in the city-state, the goal was to ensure that twenty percent of these meals will be healthier by 2020. The design studio was broadly based on the goals of the Healthy Living Master Plan, which was launched in 2014. It served as the framework for the students to conduct research and ideate near-to-far future scenarios of healthcare service and delivery for their chosen contexts.

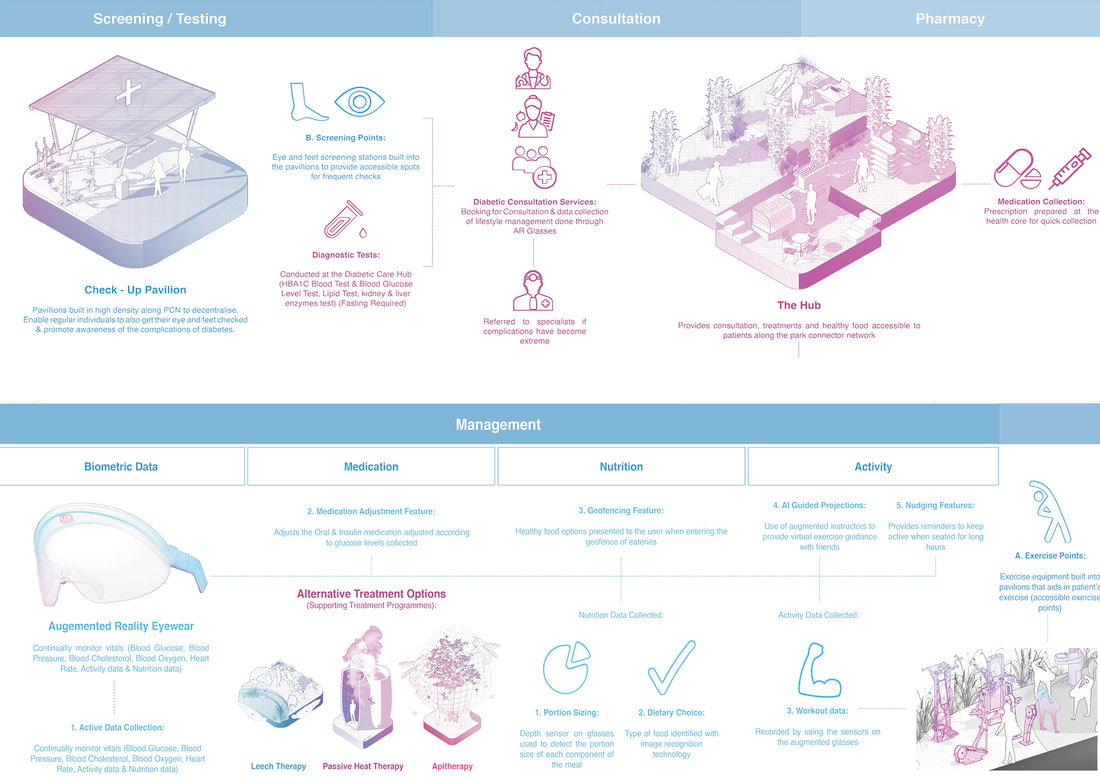

The Diabetes Care Hub

The Diabetes Care Hub team proposed a decentralised diabetic care system by introducing a distributed network of hubs and stations within Singapore's Park Connector Network (PCN). Consisting of six routes, the PCN is an island-wide network of walking and cycling paths formed by linking up the green spaces and water bodies. The new hubs and stations along the PCN created an island-wide interconnected healthcare ecosystem that seamlessly integrated preventive and care management of diabetic persons into their everyday lives. The plug-in model of the hubs and stations relieved the work of screening, consultation, and treatment from the hospitals and thereby allowing healthcare workers to focus on acute care. A person with diabetes could do a quick test at the station, housed with other exercise equipment in a specially designed pavilion. The hubs housed food outlets, community gardens, clinics, and facilities for apitherapy and leech therapy. An exciting feature was naturalised care, which the students defined as harnessing resources from Singapore's flora and fauna in diabetic treatment and management. The community gardens encouraged residents to cultivate herbs and vegetables, including the insulin plant Costus igneus. The project also incorporated AI and augmented reality technology in the integrated care experience. The digital interface informed, incentivised, and promoted active, healthy living and personal involvement in overall care management. The AR glasses and app helped persons with diabetes to monitor their meals and provided real-time tracking of their insulin levels.

Fysio

The Fysio team advocated shared responsibilities for a future healthcare system focusing on physiotherapy and promoting a healthy lifestyle. The students discovered that most residents were only a 5–10-minute walk from a community park through their research. In their project, physiotherapy was taken from the hospital setting and embedded in a park. Instead of a cold and sterile environment for the physiotherapists and their patients, they enjoyed fresh air, greenery, and services to help in the recovery process. The project also incorporated biophilic design principles in the design of healthcare facilities. The architecture students took advantage of the park's terrain to insert some of the new spaces wholly and partially below ground, connected by ramps and staircases. For example, a hydrotherapy facility located partially below ground maintained a comfortable temperature for patients undergoing rehabilitation and recovery. Technologies like autonomous vehicles, AI, and mobile robots enhanced the delivery of healthcare services and cultivated a social support network among healthcare providers, patients, and their family members.

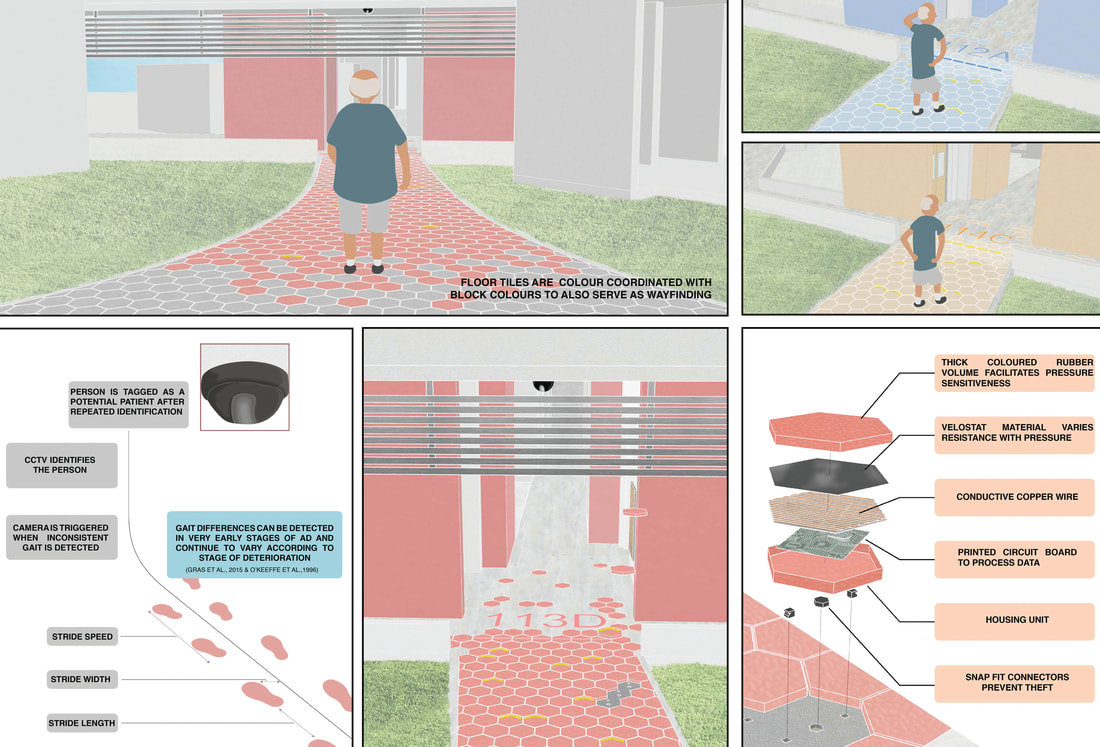

Forget Us Not

The Forget Us Not team designed an integrated care system surrounding dementia. The project focused on detection, diagnosis, and the different stages of dementia care as it progresses. The care system enabled one to lead as normal a life as possible before the onset of late-stage dementia by addressing the multiple design scales and touchpoints, from the interior of a public housing apartment to the surrounding public spaces. Like the two projects earlier, the goal was to shift the care focus from the hospital to the community for as long as possible. Through their research, the students discovered that being cared for at home was a preferred option. A neighbourhood in Singapore with a high population of senior residents was re-configured based on dementia-friendly design principles. The design of the new spaces considered materials, finishes, the geometry of footpaths, shapes of spaces, landmarks, lighting, views, colours, textures, and even smell. The project included the designing of an apartment. Flexibility, supervision, and memory-activating strategies was the overall design concept. Moreover, sensors and smart materials for detection and wayfinding added a digital infrastructural layer to the dementia-friendly neighbourhood.

Designing for Care in a Multi-Scalar and Distributed Healthcare System

Students in the Diabetes Care Hub team mapped the whole experience of a person with diabetes from management, screening, and resting to consultation and treatment. Each stage of the journey corresponded to design ideas across different scales.

Singapore's healthcare system is ranked high in the world (Statista, 2021; Bloomberg, 2014; Straits Times, 2014). The government makes efforts to ensure that healthcare remains affordable and accessible through financial subsidies, incentives to keep a healthy lifestyle, technological innovations, and careful management of costs. However, like many other countries, Singapore's healthcare system faces challenges on multiple fronts, such as an ageing population, the charge of chronic diseases like diabetes, workforce shortage, and rising costs. In 2012, the Ministry of Health set up a task force to develop a Healthy Living Master Plan (MOH, 2014; Kok, 2014). Based on feedback from Singaporeans, the task force identified the importance of a well-designed environment conducive to healthy living, that a healthy lifestyle excludes no one, and keeping costs affordable. Place, People, and Price were identified as driving forces to promote healthy living as a way of life.

For Place, the master plan envisaged a future where healthcare facilities and services will be close to and connected to parks, live and work spaces for better accessibility and seamless integration. To create a more physically inclusive environment and to encourage walking and cycling, universal and active design strategies were recommended. The Land Transport Authority is currently building an island-wide network of walkways to shelter commuters from inclement weather and encourage walking to the bus and train stations. On the other hand, residents could locate public exercise facilities and find activity programmes within two hundred metres of their homes through their mobile phones. For People, the master plan strived to promote mass participation in outdoor activities with rewards for achieving a personal target, attending health talks, and consuming healthy food. Equally important, the master plan aimed to harness the social energy of the community and sought to empower groups and individuals by training neighbourhood ambassadors and community coaches to assist professional healthcare workers. For Price, the government introduced several schemes to help low-income families and individuals access medical services. Food and beverage providers were also encouraged through incentives to offer healthier ingredients and affordable food options. As residents eat out often in the city-state, the goal was to ensure that twenty percent of these meals will be healthier by 2020. The design studio was broadly based on the goals of the Healthy Living Master Plan, which was launched in 2014. It served as the framework for the students to conduct research and ideate near-to-far future scenarios of healthcare service and delivery for their chosen contexts.

The Diabetes Care Hub

The Diabetes Care Hub team proposed a decentralised diabetic care system by introducing a distributed network of hubs and stations within Singapore's Park Connector Network (PCN). Consisting of six routes, the PCN is an island-wide network of walking and cycling paths formed by linking up the green spaces and water bodies. The new hubs and stations along the PCN created an island-wide interconnected healthcare ecosystem that seamlessly integrated preventive and care management of diabetic persons into their everyday lives. The plug-in model of the hubs and stations relieved the work of screening, consultation, and treatment from the hospitals and thereby allowing healthcare workers to focus on acute care. A person with diabetes could do a quick test at the station, housed with other exercise equipment in a specially designed pavilion. The hubs housed food outlets, community gardens, clinics, and facilities for apitherapy and leech therapy. An exciting feature was naturalised care, which the students defined as harnessing resources from Singapore's flora and fauna in diabetic treatment and management. The community gardens encouraged residents to cultivate herbs and vegetables, including the insulin plant Costus igneus. The project also incorporated AI and augmented reality technology in the integrated care experience. The digital interface informed, incentivised, and promoted active, healthy living and personal involvement in overall care management. The AR glasses and app helped persons with diabetes to monitor their meals and provided real-time tracking of their insulin levels.

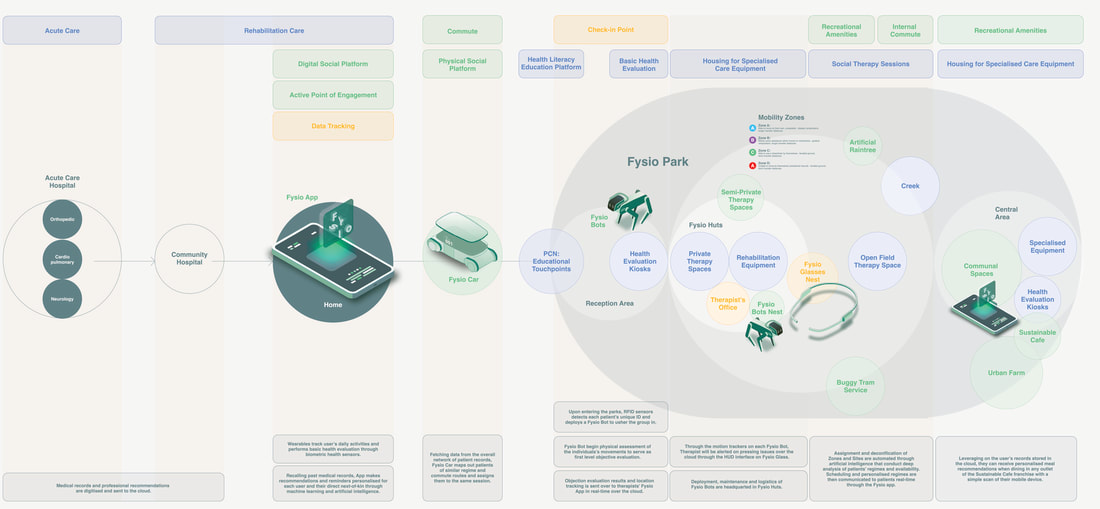

Fysio

The Fysio team advocated shared responsibilities for a future healthcare system focusing on physiotherapy and promoting a healthy lifestyle. The students discovered that most residents were only a 5–10-minute walk from a community park through their research. In their project, physiotherapy was taken from the hospital setting and embedded in a park. Instead of a cold and sterile environment for the physiotherapists and their patients, they enjoyed fresh air, greenery, and services to help in the recovery process. The project also incorporated biophilic design principles in the design of healthcare facilities. The architecture students took advantage of the park's terrain to insert some of the new spaces wholly and partially below ground, connected by ramps and staircases. For example, a hydrotherapy facility located partially below ground maintained a comfortable temperature for patients undergoing rehabilitation and recovery. Technologies like autonomous vehicles, AI, and mobile robots enhanced the delivery of healthcare services and cultivated a social support network among healthcare providers, patients, and their family members.

Forget Us Not

The Forget Us Not team designed an integrated care system surrounding dementia. The project focused on detection, diagnosis, and the different stages of dementia care as it progresses. The care system enabled one to lead as normal a life as possible before the onset of late-stage dementia by addressing the multiple design scales and touchpoints, from the interior of a public housing apartment to the surrounding public spaces. Like the two projects earlier, the goal was to shift the care focus from the hospital to the community for as long as possible. Through their research, the students discovered that being cared for at home was a preferred option. A neighbourhood in Singapore with a high population of senior residents was re-configured based on dementia-friendly design principles. The design of the new spaces considered materials, finishes, the geometry of footpaths, shapes of spaces, landmarks, lighting, views, colours, textures, and even smell. The project included the designing of an apartment. Flexibility, supervision, and memory-activating strategies was the overall design concept. Moreover, sensors and smart materials for detection and wayfinding added a digital infrastructural layer to the dementia-friendly neighbourhood.

Designing for Care in a Multi-Scalar and Distributed Healthcare System

Students in the Diabetes Care Hub team mapped the whole experience of a person with diabetes from management, screening, and resting to consultation and treatment. Each stage of the journey corresponded to design ideas across different scales.

Fig 3. Final experience journey mapping and design incorporating the entire user experience of a person with diabetes and the multi-scalar design solutions.

The Fysio team looked at an integrated service experience of different physiotherapy patients based on their levels of mobility. It started with a new interface on the patient's smartphone to boarding a self-driving electric shuttle and bringing the patient to the nearby park. A community coach or a robot pet accompanied the patient throughout the different sessions depending on the level of need.

Fig 4. Designing the different platforms and scales of engagement for a distributed physiotherapy experience in a park.

For the Forget Us Not team working on the topic of dementia, the students created an experience journey consisting of detection, diagnosis, and three care stages from early to mid and late. Each stage of their experience map listed the challenges faced by the patients, their caregivers, and healthcare providers, together with the envisioned solutions from the home to the neighbourhood.

Fig 4. Combination of digital monitoring and sensors embedded in the floor tiles for detection and assisting a person with dementia in wayfinding.

Unlike most architecture studios where the design of the building and the site takes centre stage, all three projects had to design across the scales of the object, interior, building, and site. Another distinction was that the site was not assigned beforehand. The choice of possible sites was discussed and determined during the Framing phase when the teams had a clearer idea of their projects. In addition, each team came up with a service design strategy to accompany the spatial solutions.

During the semester, the students shared their ideas with healthcare practitioners, social workers, experience designers, architects, and industrial designers in several mini-presentations. The feedback was invaluable not only for the students but the guest reviewers as well. One social worker from a foundation helping elderly residents with their healthcare needs was impressed by the level of sensitivity, thoughtfulness and comprehensiveness. Another healthcare practitioner found the idea of using insects to help manage diabetes unusual and provocative. She gave valuable suggestions on how her patients would respond to this unconventional treatment. The opportunities to present their ideas to various stakeholders helped the students to refine their initial thoughts and validated some of their design decisions. From the students' feedback, the mini-presentations gave them the sense of being part of a larger community of professionals confronting similar healthcare challenges. They felt the experience made their fledgling design contributions worthwhile and meaningful.

Designing for Care in Through Empathetic Design

An important goal in the Healthcare 2030 studio was the cultivation of empathy. The assignments enabled students to experience, interpret and assess their design proposals from the perspective of their future users. The industrial design students were familiar with experience journey maps, user interviews, and sensitising exercises. However, it was a new experience for the architecture students who were used to site, form, and programme. They initially struggled with the new approach but, over time, were able to see the benefits. Through examples in practice (Gensler 2017; Lau 2015) and studio conversations, the architecture students saw that the expanded process complemented and added value to their work as future architects.

In their essay What Happened to Empathic Design?, authors Mattelmaki, Vaajakallio, and Koskinen identified four layers of sensitivity in empathetic design (Mattelmäki et al. 2013). They are sensitivity to humans, design, technique, and collaboration. To encourage sensitivity to humans, students interviewed the patients, healthcare providers, and stakeholders at their homes, clinics, care centres, and offices. The Fysio team interviewed physiotherapists at their clinics and tried out the sessions and machines designed to identify, treat and manage various injuries and chronic conditions. The experience allowed them to contextualise the difficulties faced, such as the cramped interiors, the lack of natural light, noise, and confusing appointment-making process. For sensitivity to design, the What If? question provided the students with an imaginative leap based on what they uncovered from their research in the discovery phase. For sensitivity to technique, students prototyped the experience as if they were patients using the product or services. In the case of the Diabetes Care Hub, they made a video of using the smart goggle while cycling along the park connector. The video documented the entire experience of wearing the google while cycling and finishing at a local eating outlet. It highlighted how the information from the goggle could help monitor the insulin level and recommend suitable food based on insulin sensitivity or blood sugar level. Students in the Forget Us Not group researched the different colours and scents that flowering plants emit. Their new design for the pathways was based on colours and smell to help with the declining sense of orientation and spatial navigation of a person who has dementia. For collaboration, the mini-presentations turned a traditional architectural review experience of critique and defence into one where the students and the guests put their thinking hats together to refine the proposals. In this joint studio, we included the fifth layer of sensitivity, which is nature. To be sensitive to nature calls for a design to care for humans and our environment. In her book Designing Cultures of Care, Laurene Vaughan writes,

Care needs to embrace the entire ecosystem that we inhabit and practice within.

(Vaughan 2018, 8)

Vaughan further emphasises that,

From this perspective, it can be argued that design as practice of care would be a relational practice- that is, founded on the relationship between the designer and the contexts, within a range of proximities, of their practice. (Vaughan 2018, 8).

One of the central framings of the Diabetes Care Hub team was the question, What does it mean to care? The students broke down care into three categories. First, as an action or the practice of care. Second, care as connected and engaged in shared experiences. Third, care as creating awareness to motivate actions of care. The students introduced community gardens in the care hub to bring the residents together. Medicinal plants for complementary diabetes therapy were proposed in the gardens and used in food preparation, while a digital interface nudged the user to be more involved in self-management. At the architectural level, the students introduced biophilic design principles. The form, materials, and programmes of the care hub reconnected the residents’ everyday life to nature and improved the health and well-being of everyone in the community.

Similarly, the Fysio team used the new semi-underground and underground spaces to maintain a constant and comfortable temperature for physiotherapy sessions in hot and humid Singapore. Evaporative cooling through the therapy and reflective pools further aided the cooling process. These water bodies also fostered a multisensorial physiotherapy experience instead of a clean and sterile clinic.

Conclusion

The paper offers a re-tooled design studio experience by drawing ideas from the Healthcare 2030 studio grounded on a collaborative, multi-disciplinary, multi-scalar, and multi-stakeholder approach. The goal of designing a connected care system across different scales, touchpoints, and sites compelled architecture and industrial design students to question their respective disciplines' assumptions, work collaboratively, and find common grounds amidst the differences. After the semester, the DesignSingapore Council co-sponsored a public exhibition of the projects at the National Design Centre. Students from three teams were also awarded internship opportunities in a global consultancy firm, and the Fysio team won an honourable mention in a healthcare design competition. On the other hand, a local architecture and design magazine featured the Diabetes Care Hub project for its innovative, multi-scalar, and comprehensive solutions. We were initially unsure how the studio will turn out due to the different approaches in teaching and learning design between architecture and industrial design. However, the numerous recognitions received by students affirmed that the decision to hold the joint design studio was the right one. It was a remarkable conclusion to the thirteen-week experiment to open up and re-imagine architecture education through the design of a distributed healthcare system in Singapore.

References

Architects Registration Board (2021) Modernising the initial education and training of architects. Discussion document.Retrieved September 11 2022, from https://arb.org.uk/arb-announces-fundamental-reforms-to-architectural-education-2/

Bloomberg (2014). Most Efficient Health Care Around the World. Bloomberg Visual Data. Retrieved September 5 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/infographics/most-efficient-health-care-around-the-world.html?leadSource=uverify%20wall

Boyer E, Mitgang L (1996) Building Community: A New Future for Architecture Education and Practice: A Special Report. Jossey-Bass Inc, California.

Buchanan, Peter (2012) The Big Rethink Part 9: Architectural Education. The Architectural Review. Retrieved September 11, 2022, from https://www.architectural-review.com/archive/campaigns/the-big-rethink/the-big-rethink-part-9-rethinking-architectural-education

Dutton, T (1987). Design and Studio Pedagogy, Journal of Architectural Education, 41(1): 16-25, DOI: 10.1080/10464883.1987.10758461.

Gensler 2017. Gensler Experiential Index. Retrieved September 24, 2022, from https://www.gensler.com/gri/experience-index

Kok, Xin Hui (April 24, 2014) Master plan aims to give S’poreans more healthy living options by 2020. The Straits Times. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/master-plan-aims-give-sporeans-more-healthy-living-options-2020. Assessed 5 Sep 2022

Lau D (2015). User Experience Design vs. Architecture. Medium. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://medium.com/@davidlau/user-experience-design-vs-architecture-d5fce196a8e9#:~:text=Architectural%20design%20is%20basically%20user,version%20of%20a%20mobile%20app

Mattelmäki T, Vaajakallio, K, Koskinen, I (2014). What Happened to Empathic Design? Design Issues 30(1): 67-77.

Ministry of Health (n.d.). The Healthy Living Master Plan. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/reports/the-healthy-living-master-plan

Nicol D, Pilling S (2000). Changing Architectural Education. Towards a New Professionalism. Spon Press, London.

Statista (2021). Health and health systems ranking of countries worldwide in 2021, by health index score. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1290168/health-index-of-countries-worldwide-by-health-index-score/

Straits Times. (27 NOV 2014). Singapore ranked world's No. 2 for health-care outcomes. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/singapore-ranked-worlds-no-2-for-health-care-outcomes-eiu

Vaughan, L (ed) (2018) Designing Cultures of Care. Bloomsbury Visual Arts, London.

During the semester, the students shared their ideas with healthcare practitioners, social workers, experience designers, architects, and industrial designers in several mini-presentations. The feedback was invaluable not only for the students but the guest reviewers as well. One social worker from a foundation helping elderly residents with their healthcare needs was impressed by the level of sensitivity, thoughtfulness and comprehensiveness. Another healthcare practitioner found the idea of using insects to help manage diabetes unusual and provocative. She gave valuable suggestions on how her patients would respond to this unconventional treatment. The opportunities to present their ideas to various stakeholders helped the students to refine their initial thoughts and validated some of their design decisions. From the students' feedback, the mini-presentations gave them the sense of being part of a larger community of professionals confronting similar healthcare challenges. They felt the experience made their fledgling design contributions worthwhile and meaningful.

Designing for Care in Through Empathetic Design

An important goal in the Healthcare 2030 studio was the cultivation of empathy. The assignments enabled students to experience, interpret and assess their design proposals from the perspective of their future users. The industrial design students were familiar with experience journey maps, user interviews, and sensitising exercises. However, it was a new experience for the architecture students who were used to site, form, and programme. They initially struggled with the new approach but, over time, were able to see the benefits. Through examples in practice (Gensler 2017; Lau 2015) and studio conversations, the architecture students saw that the expanded process complemented and added value to their work as future architects.

In their essay What Happened to Empathic Design?, authors Mattelmaki, Vaajakallio, and Koskinen identified four layers of sensitivity in empathetic design (Mattelmäki et al. 2013). They are sensitivity to humans, design, technique, and collaboration. To encourage sensitivity to humans, students interviewed the patients, healthcare providers, and stakeholders at their homes, clinics, care centres, and offices. The Fysio team interviewed physiotherapists at their clinics and tried out the sessions and machines designed to identify, treat and manage various injuries and chronic conditions. The experience allowed them to contextualise the difficulties faced, such as the cramped interiors, the lack of natural light, noise, and confusing appointment-making process. For sensitivity to design, the What If? question provided the students with an imaginative leap based on what they uncovered from their research in the discovery phase. For sensitivity to technique, students prototyped the experience as if they were patients using the product or services. In the case of the Diabetes Care Hub, they made a video of using the smart goggle while cycling along the park connector. The video documented the entire experience of wearing the google while cycling and finishing at a local eating outlet. It highlighted how the information from the goggle could help monitor the insulin level and recommend suitable food based on insulin sensitivity or blood sugar level. Students in the Forget Us Not group researched the different colours and scents that flowering plants emit. Their new design for the pathways was based on colours and smell to help with the declining sense of orientation and spatial navigation of a person who has dementia. For collaboration, the mini-presentations turned a traditional architectural review experience of critique and defence into one where the students and the guests put their thinking hats together to refine the proposals. In this joint studio, we included the fifth layer of sensitivity, which is nature. To be sensitive to nature calls for a design to care for humans and our environment. In her book Designing Cultures of Care, Laurene Vaughan writes,

Care needs to embrace the entire ecosystem that we inhabit and practice within.

(Vaughan 2018, 8)

Vaughan further emphasises that,

From this perspective, it can be argued that design as practice of care would be a relational practice- that is, founded on the relationship between the designer and the contexts, within a range of proximities, of their practice. (Vaughan 2018, 8).

One of the central framings of the Diabetes Care Hub team was the question, What does it mean to care? The students broke down care into three categories. First, as an action or the practice of care. Second, care as connected and engaged in shared experiences. Third, care as creating awareness to motivate actions of care. The students introduced community gardens in the care hub to bring the residents together. Medicinal plants for complementary diabetes therapy were proposed in the gardens and used in food preparation, while a digital interface nudged the user to be more involved in self-management. At the architectural level, the students introduced biophilic design principles. The form, materials, and programmes of the care hub reconnected the residents’ everyday life to nature and improved the health and well-being of everyone in the community.

Similarly, the Fysio team used the new semi-underground and underground spaces to maintain a constant and comfortable temperature for physiotherapy sessions in hot and humid Singapore. Evaporative cooling through the therapy and reflective pools further aided the cooling process. These water bodies also fostered a multisensorial physiotherapy experience instead of a clean and sterile clinic.

Conclusion

The paper offers a re-tooled design studio experience by drawing ideas from the Healthcare 2030 studio grounded on a collaborative, multi-disciplinary, multi-scalar, and multi-stakeholder approach. The goal of designing a connected care system across different scales, touchpoints, and sites compelled architecture and industrial design students to question their respective disciplines' assumptions, work collaboratively, and find common grounds amidst the differences. After the semester, the DesignSingapore Council co-sponsored a public exhibition of the projects at the National Design Centre. Students from three teams were also awarded internship opportunities in a global consultancy firm, and the Fysio team won an honourable mention in a healthcare design competition. On the other hand, a local architecture and design magazine featured the Diabetes Care Hub project for its innovative, multi-scalar, and comprehensive solutions. We were initially unsure how the studio will turn out due to the different approaches in teaching and learning design between architecture and industrial design. However, the numerous recognitions received by students affirmed that the decision to hold the joint design studio was the right one. It was a remarkable conclusion to the thirteen-week experiment to open up and re-imagine architecture education through the design of a distributed healthcare system in Singapore.

References

Architects Registration Board (2021) Modernising the initial education and training of architects. Discussion document.Retrieved September 11 2022, from https://arb.org.uk/arb-announces-fundamental-reforms-to-architectural-education-2/

Bloomberg (2014). Most Efficient Health Care Around the World. Bloomberg Visual Data. Retrieved September 5 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/infographics/most-efficient-health-care-around-the-world.html?leadSource=uverify%20wall

Boyer E, Mitgang L (1996) Building Community: A New Future for Architecture Education and Practice: A Special Report. Jossey-Bass Inc, California.

Buchanan, Peter (2012) The Big Rethink Part 9: Architectural Education. The Architectural Review. Retrieved September 11, 2022, from https://www.architectural-review.com/archive/campaigns/the-big-rethink/the-big-rethink-part-9-rethinking-architectural-education

Dutton, T (1987). Design and Studio Pedagogy, Journal of Architectural Education, 41(1): 16-25, DOI: 10.1080/10464883.1987.10758461.

Gensler 2017. Gensler Experiential Index. Retrieved September 24, 2022, from https://www.gensler.com/gri/experience-index

Kok, Xin Hui (April 24, 2014) Master plan aims to give S’poreans more healthy living options by 2020. The Straits Times. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/master-plan-aims-give-sporeans-more-healthy-living-options-2020. Assessed 5 Sep 2022

Lau D (2015). User Experience Design vs. Architecture. Medium. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://medium.com/@davidlau/user-experience-design-vs-architecture-d5fce196a8e9#:~:text=Architectural%20design%20is%20basically%20user,version%20of%20a%20mobile%20app

Mattelmäki T, Vaajakallio, K, Koskinen, I (2014). What Happened to Empathic Design? Design Issues 30(1): 67-77.

Ministry of Health (n.d.). The Healthy Living Master Plan. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/reports/the-healthy-living-master-plan

Nicol D, Pilling S (2000). Changing Architectural Education. Towards a New Professionalism. Spon Press, London.

Statista (2021). Health and health systems ranking of countries worldwide in 2021, by health index score. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1290168/health-index-of-countries-worldwide-by-health-index-score/

Straits Times. (27 NOV 2014). Singapore ranked world's No. 2 for health-care outcomes. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/singapore-ranked-worlds-no-2-for-health-care-outcomes-eiu

Vaughan, L (ed) (2018) Designing Cultures of Care. Bloomsbury Visual Arts, London.