|

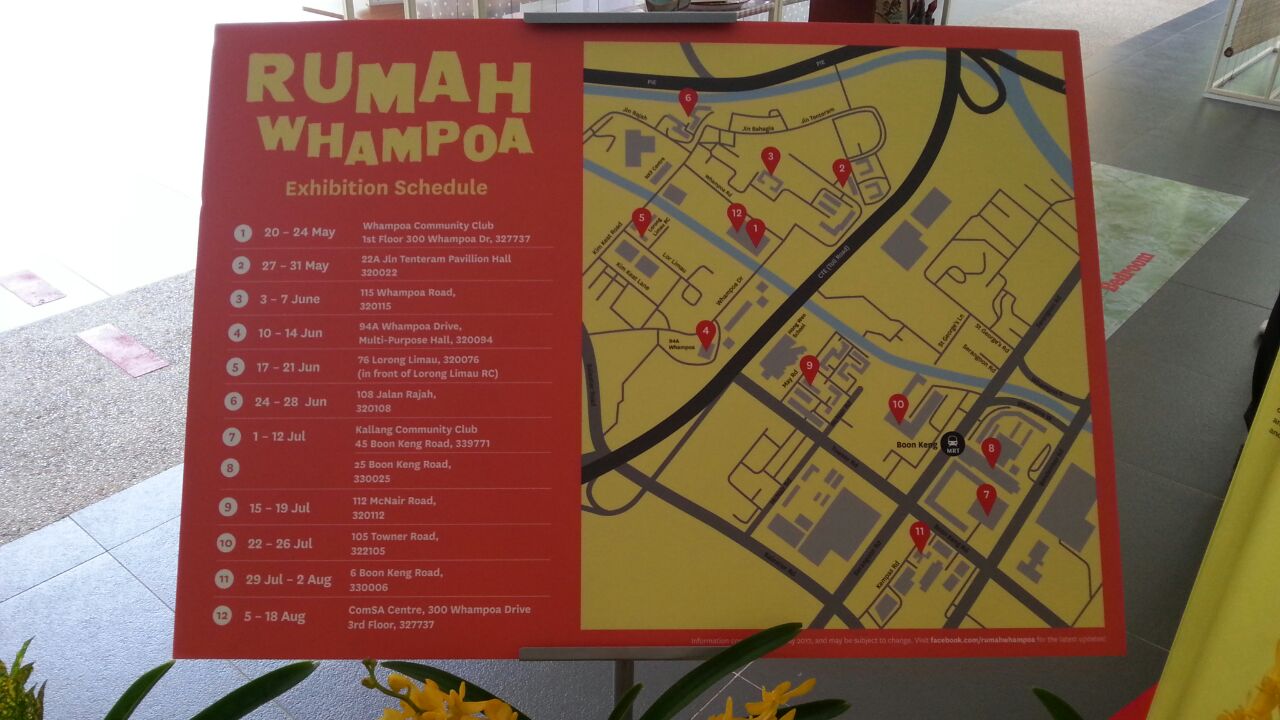

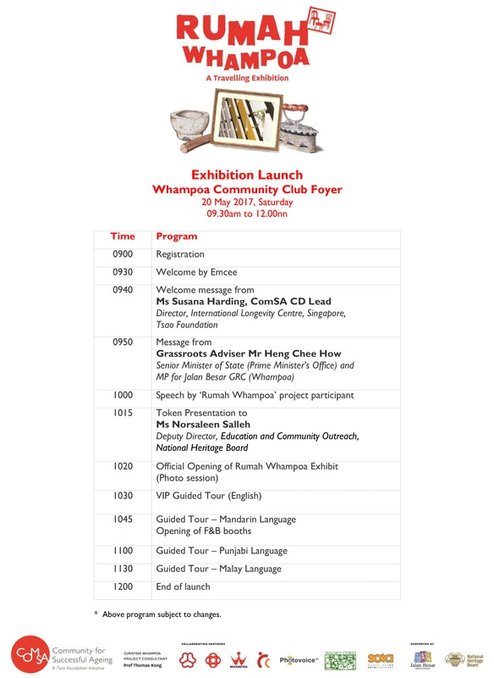

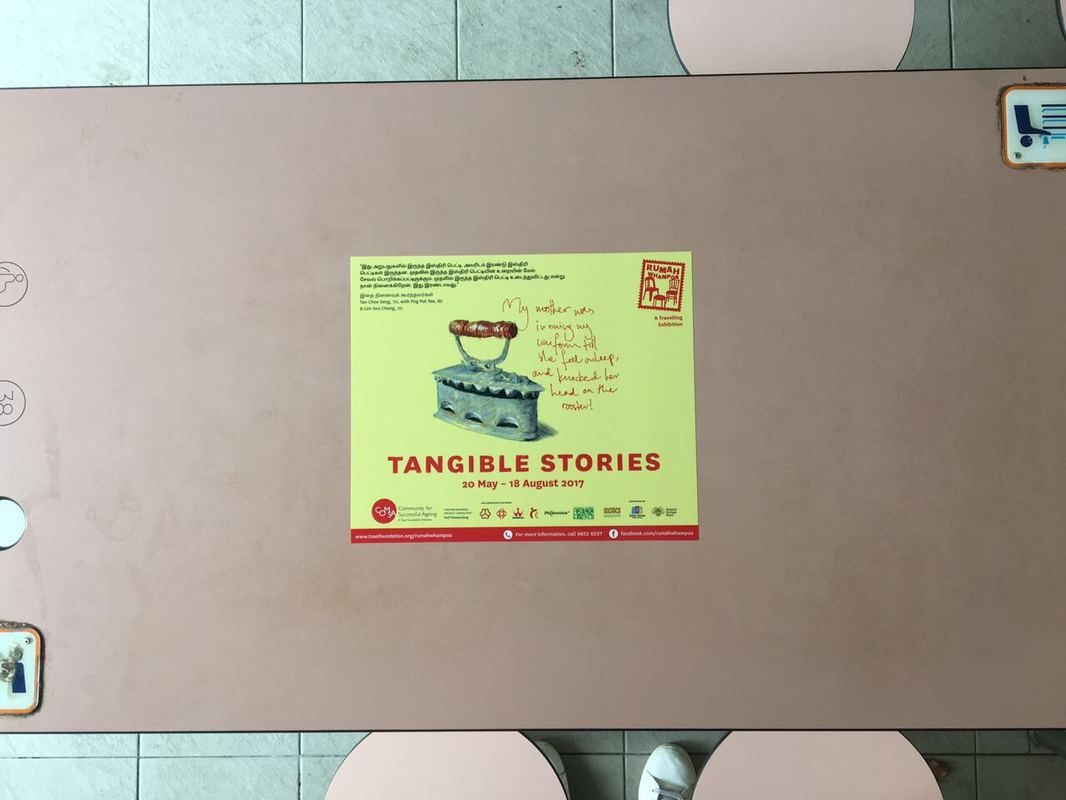

Rumah Whampoa presents two community engagement projects--Tangible Stories & Photo Voice—which the Whampoa senior residents participated in over the last six months. Conceptualized by various art collaborators residing locally and overseas, Rumah Whampoa exhibits a collection of verbal and visual narratives about the lives in Whampoa, as told by its senior residents. In Tangible Stories, the residents shared their personal stories of objects that had stayed with them over the years, and which they have kept as they moved into Whampoa. In Photo Voice, the residents learnt digital photography and in turn, presented their view of Whampoa through the photographic lens. Curatorial Concept The exhibition focuses on the idea of welcoming others into the lives of these senior residents. Styled with materials that harkens the past and using the concept of a rumah (home), the narratives are clustered by the areas that define activities in the home: outdoor play area, cooking/eating area, bedroom/study, etc. At each of these areas, the verbal and visual narratives captured through the two projects intermingle. The exhibition operates at two levels, presenting snapshots and anecdotal accounts as well as inviting the audience to be curious and to pick up some of these objects, further discovering some of the personal histories associated with them. Designed to be portable, these modular clusters are reconfigured at each new site which hosts the exhibition. In that way, a new variant and interpretation of “Home Whampoa” is created each time. Text by Jacelyn Kee. Exhibition design by Fellow. http://www.wearefellow.co/

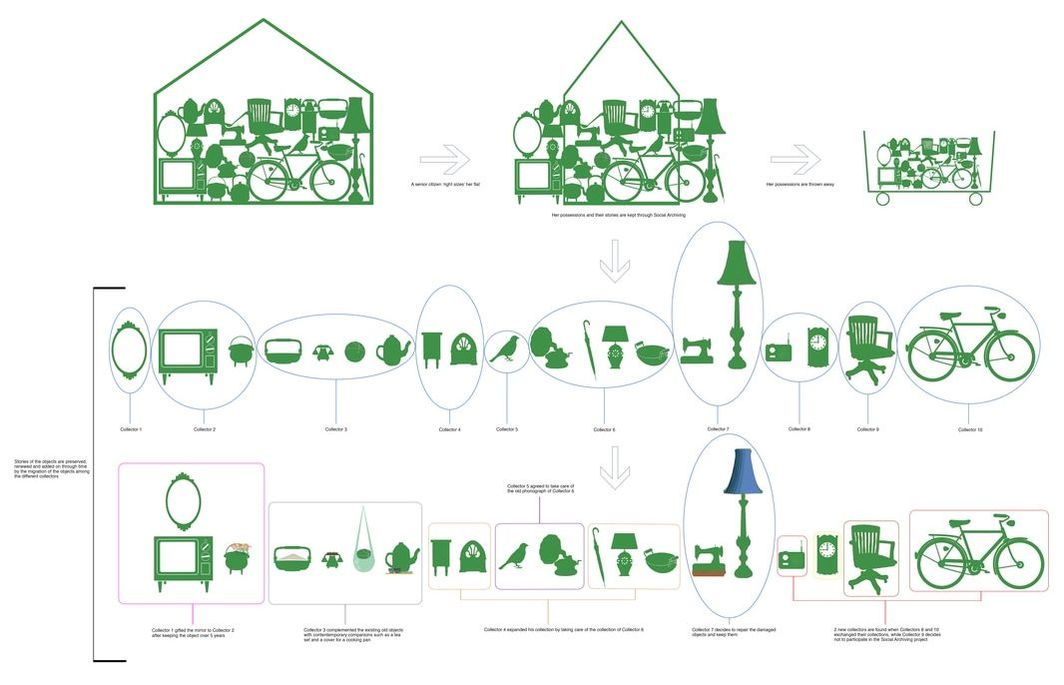

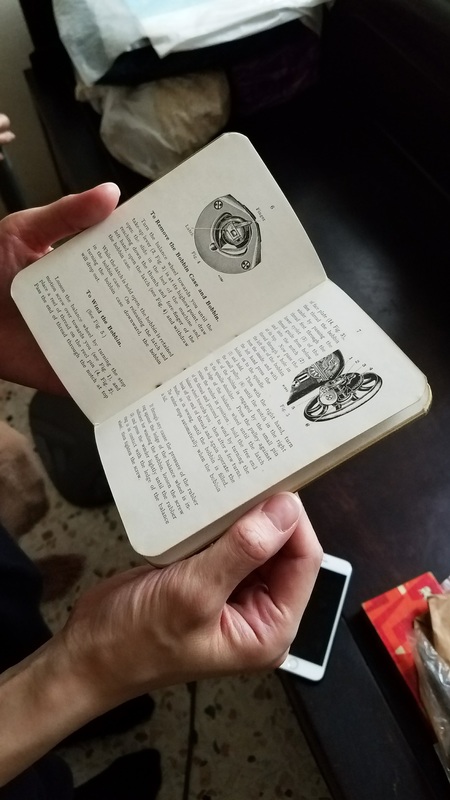

"...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears."

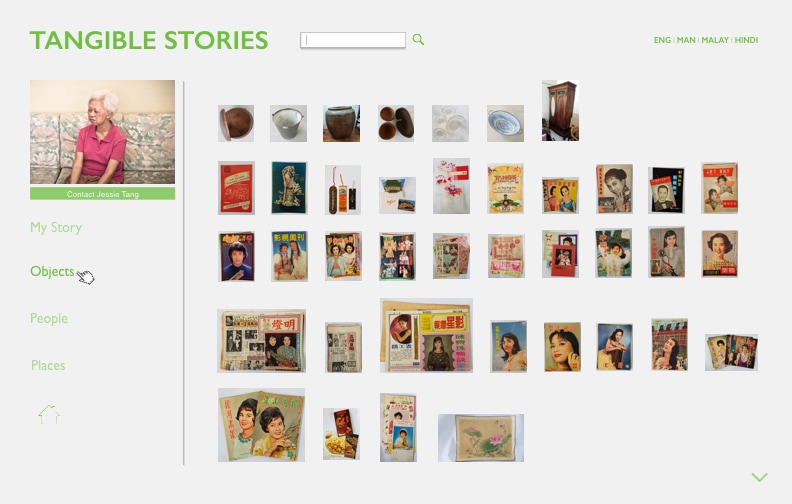

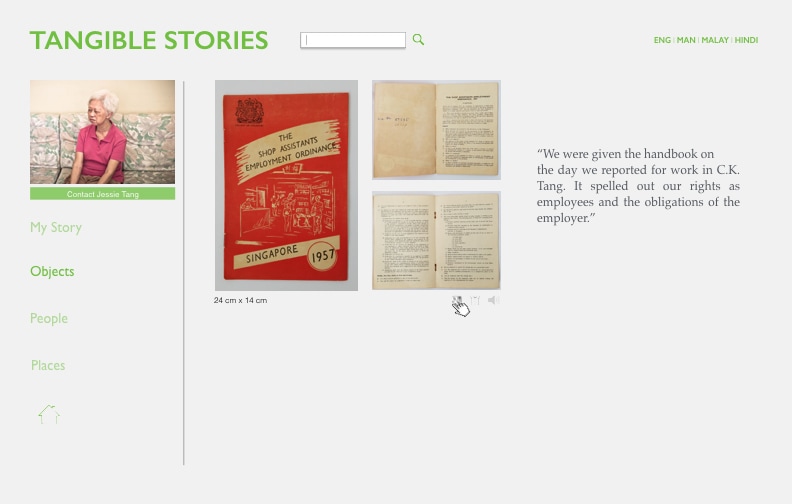

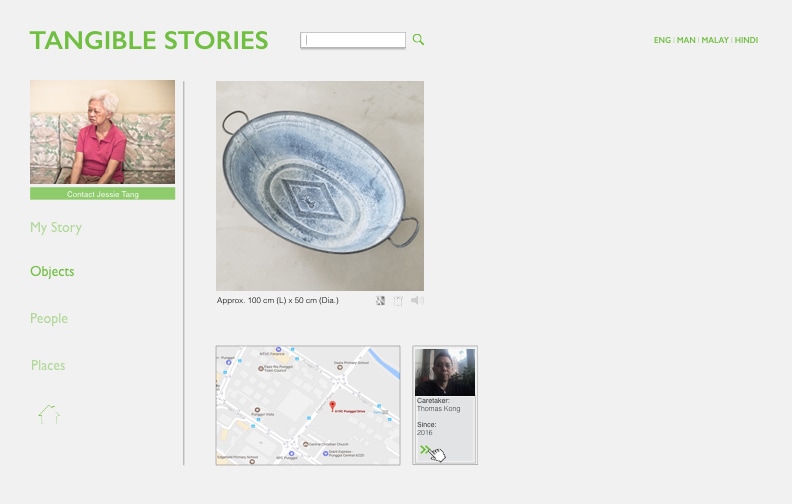

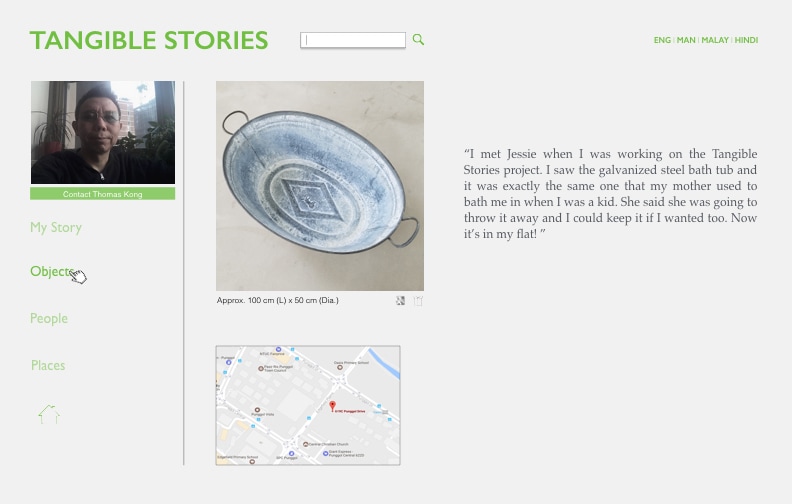

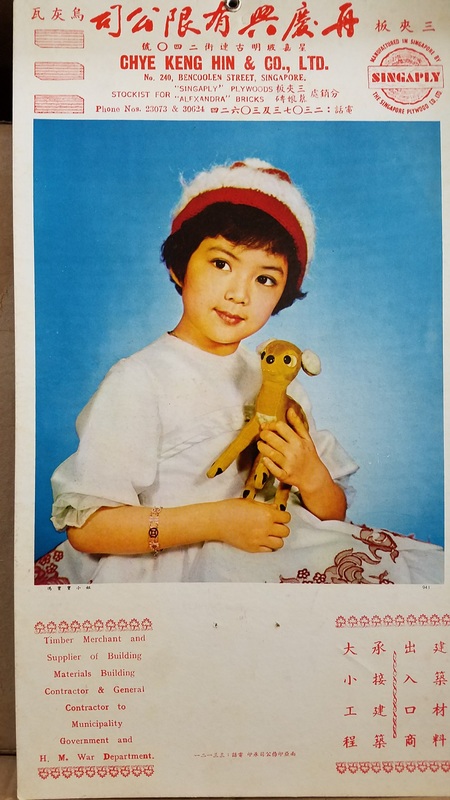

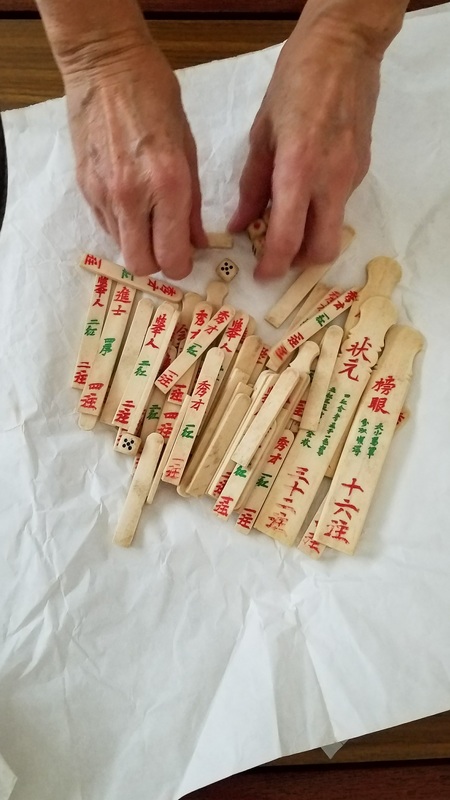

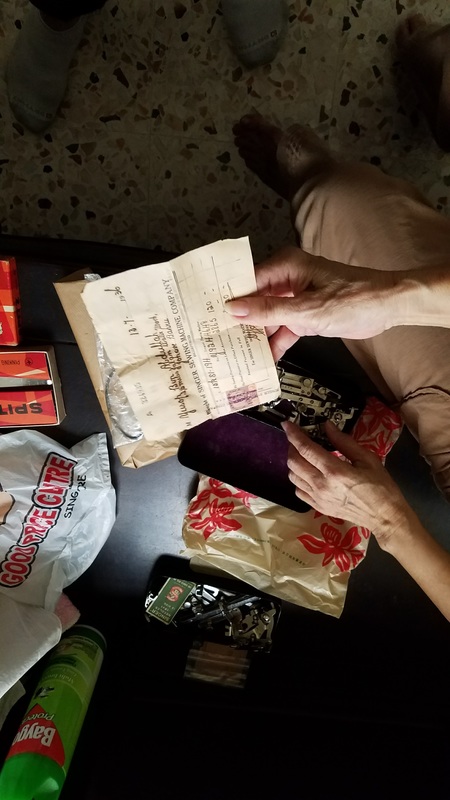

Lewis Hyde. The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World. Social Archiving explores a new form of archiving that combines gift giving, safekeeping, curating, placemaking and a renewal of the life of a collection through a simple in-person ritual and a digital interface for sustaining the social life of the collection nationally and beyond. I conceived of Social Archiving as a new model of caring for objects and ephemera that carry cultural and heritage value. It is a platform for intergenerational learning in-place and online, public stewardship and the building of a personal legacy through the sharing of the stories related to the archived materials. Social archiving was motivated by the diminishing size of an elderly’s home and a rapidly aging population in the city-state. Social Archiving draws from the rich tradition of archiving as an art form and differs from current institutional model of archiving in the following ways: 1. It is interdisciplinary. The process in itself constitutes a participatory form of art-making and sharing. 2. Although Social Archiving has a precedent in the rich tradition of archival art, it does not rest purely as a one off art project. Social Archiving helps in the crafting of interactions and relational structures in the design of spatial strategies to address contemporary urban concerns. Specific to this proposal are the issues of aging in place, personal legacy, identity, community forming and the spaces that support them. 3. It relies on the interest, passion, care and housing offered by a community of volunteer archivists/collectors/curators instead of the control and management of an institution. 4. It promotes social interaction, both digital and in real time in the archival process. 5. It encourages active, creative re-interpretation and curating of the archived materials that extends beyond the passive role of offering a storage space. 6. It recognizes the role social media plays maintaining contact between archivists, between the original owner and the new collector, and in the organization, dissemination and sharing of the archived materials. 7. It permits the transferring of the archived materials if the new collector agrees to the role and expectations. 8. It is a scalable process that can range from an intimate social setting to a large, community-level interaction. The populations of Asia and Western Europe are rapidly aging and 60% of the world's population is in Asia. Although the project is situated in Singapore, the issues, challenges and opportunities surrounding aging are global while the initiatives to address this rising societal phenomenon are potentially transferable to other nations. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/what-singapores-plan-for-an-aging-population-can-teach-the-us/2015/11/01/f86e9596-7f42-11e5-b575-d8dcfedb4ea1_story.html) Singapore is a particularly important case study because it has one of the world's fastest aging population. Over 80% of its population lives in high rise public housing given the limited land available for development. As the government encourages its citizens to see their apartments as economic assets, it is not uncommon for many to sell, buy and live in several apartments over their lifetimes. Each move generates bigger profits that serve as their retirement nest eggs. Through my encounter with the senior citizens in the course of the Tangible Stories project, I foresee the Social Archiving project can take on a significant role in the social and cultural landscape of Singapore based on the following reasons: 1. As more and more senior residents move into nursing and retirement homes, as well as smaller studio apartments, they are confronted by the challenge of holding on to their cherished possessions acquired over the years. These possessions include furniture, objects for daily use and print materials that house strong memories for them. Unfortunately, many senior citizens have to either sell or throw them away now, especially if they are single or do not have children to pass these objects and materials to. Moreover, some of their children may not be keen to take over their parents’ possessions. 2. Given the unceasing urban transformation and the rapidly aging population in the city-state, many grassroots level memories are lost despite the attempts to collect them through the massive, national-level Singapore Memory Project. Social archiving offers a more intimate platform for intergenerational learning and remembering through the sharing of the stories related to the archived materials. As Arthur C. Brooks in his Op-Ed piece for the New York Times wrote. "One million is a statistic. One is a human story." 3. As more and more studio flats are designed within existing and matured housing estates, there is an urgent need to give greater consideration to the design of public spaces that promotes aging in community. Besides design considerations such as universal access, elder friendly interiors, etc., the provision of spaces and the holding of community events that help anchor personal memories of place can be promoted through social archiving. Partners: Jacelyn Kee; Lee Sze-Chin; Asian Film Archive; Tangs Holdings; Tsao Foundation. I spent several hours over the weekend listening to longtime Whampoa resident Jessie Tang's stories of her collection of objects. They were neatly and carefully kept in photo albums, boxes, jars and wrapped in old newspapers that showed the passing of time. Besides the smaller objects, she has several beautiful antique furniture left behind by her mother. From the retelling of her love for Chinese opera as a young adult and her collection of old Chinese opera newspapers from Hong Kong from as far back as the 1930s, I came to know of a vibrant Chinese opera scene in Singapore. During that era, Hong Kong opera troupes would often come perform in local theaters to an enthusiastic local crowd. Their impending presences were announced in colorful flyers that Jessie fervently collected as well. Besides performing in operas, the artistes also acted in movies. Alongside the Chinese Opera newspapers, Jessie has an extensive collection of old movie star magazines featuring well-known Hong Kong and Chinese actors in the 1950s. My childhood memories flooded back as I flipped the pages of the magazines. I recognized pictures of Tse Yin, Fung Bo Bo and Sek Kin, to name a few, who were in the prime of their careers at that time. Our conversation took place in different parts of her home, and transitioned from one collection to another, such as her mother’s Singer sewing machine that included accessories and a receipt dated 1936; her old Scholar’s game made from animal bones; her extensive collection of Chinese red packets; her collection of paper cranes she made, and her one and only porcelain model of the old C.K. Tang building. Jessie worked in C.K Tang since the day it opened for business till her retirement in 2008. With each collection, a new insight into the life of this incredible lady was revealed.

In the Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade avoided her death by telling an endless chain of folktales to King Shahryar each night. Her stories prevented the King from ordering her execution at the dawn of each day as he was mesmerized by the unbroken web of folktales. I felt the same when I was in Jessie’s flat- an intriguing and fascinating place where in the course of 30 years, it evolved into a Living Museum housing her rich and assorted collections. Her weaving of everyday life, memories, personal stories, histories and cherished objects left me enthralled and desiring for more. The story of the Wa Fu community space began almost 30 years ago. The place was a destination for residents living in the near by housing estate to leave their statues of porcelain deities when they relocated or when the religion was no longer practiced by the younger generation after the passing of the elderly family member. The stepped profile of the ground leading to the sea is an ideal site to place the deities. They are secured individually by a layer of cement to prevent them from toppling over during a typhoon. Through time, a sea of porcelain deities slowly emerges and are they cared for by a group of elderly residents. Some deities are protected by simple shelters while others share their spaces with toy figurines that were also left here. A self-constructed shelter serves as both a community space for the elderly and for them to keep their belongings. A well close-by provides fresh water for cleaning after taking a dip in the sea. We were told it is a popular activity among the elderly and younger residents. Some come for a swim early in the morning before heading off to work.

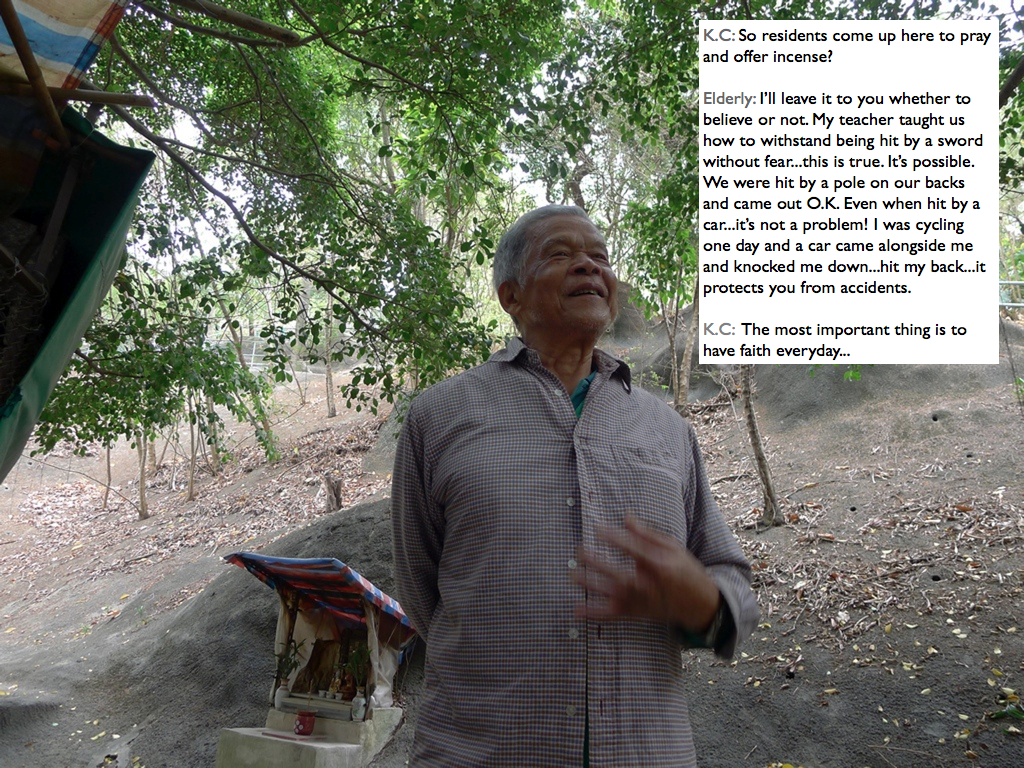

The hillside informal shrine in So Uk Estate is connected to a larger network of elderly walkers and informal social spaces. The shrine is situated along a path that winds up the hillside, which is a favorite spot for the mostly elderly residents and housewives to engage in their morning walks and exercises. The shrine is often a stop over for the residents. They would offer incense or a simple prayer at the shrine on their way up or down the hill during their morning exercise routines. Besides exercising, the residents have also undertaken small, self-initiated actions along the various exercising spots; such as plant caring, building of small concrete steps to link disconnected parts of the hillside and allow a safer walk up the hill, introducing resting spots, setting up support facilities for the morning exercises, and repairing broken planters. Water for the plants is collected from the natural run-offs from the hill in small pails and buckets. The So Uk Estate shrine and the adjacent exercising spots are excellent examples of bottom-up initiatives in place-making. It makes a strong case for allowing urban dwellers to take control and have the opportunity to shape their immediate spaces in the city rather than top-down initiatives that often miss the point and cost much more than they should be.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed