|

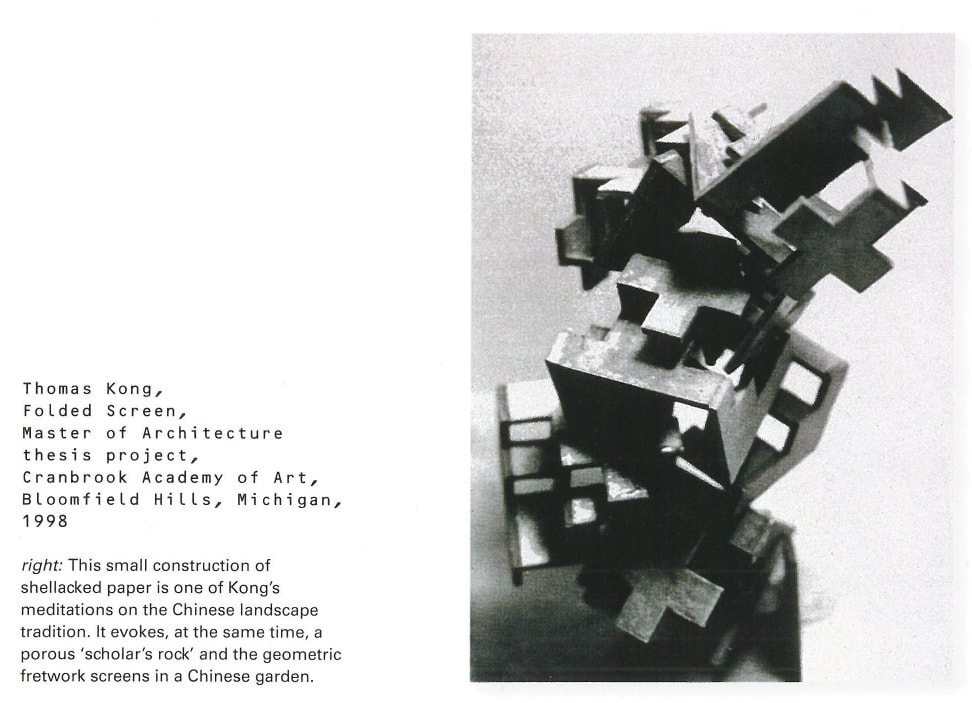

I am honoured to have my work featured by Cranbrook Academy of Art Artist-in-Residence Peter Lynch in the recent issue of Architecture Design.

I often look back to the Chinese language in order to see things anew. The word mobility comprises of two characters, one refers to 'grain' and 'many', while the other to 'clouds' and 'force/energy'. Grains and clouds- the earth and the sky- How poetic! We use the terms 'Cloud Computing' and 'Cloud Storage' now to suggest the freedom and ubiquitous nature of computing and an era of unlimited digital storage. One is no longer tied down to a specific object or is accessibility limited.

Clouds do not have definite edges or shapes and they do not recognize boundaries. Clouds drift. Clouds are not bubbles, which are hermetic, sealed off from the world. Clouds receive, collect and hold until their formless states become tangible falling clouds when they could not resist the force of gravity. The falling clouds from the sky nourish the life of the grains that in turn sustain human life on earth. Metaphors are still important, just like how Louis Kahn and Ann Tyng re-directed our understanding of traffic flows, buildings and infrastructures in their traffic study of Philadelphia with a new notation system and by calling them rivers, docks and harbors. In Greek, a metaphor means 'to carry', to 'transfer'. Isn't that what we partake every day on the way to work, to pick up our kids, and back? Unlike a subway line that serves a singular function, I wonder how do we imagine a 21st C Mobility Cloud housing a multiplicity of scales, movements, durations and experiences that not only carries and transfers but also nourishes and sustains our wellbeing? The word design is often used as a noun and a verb. The OED defines design as

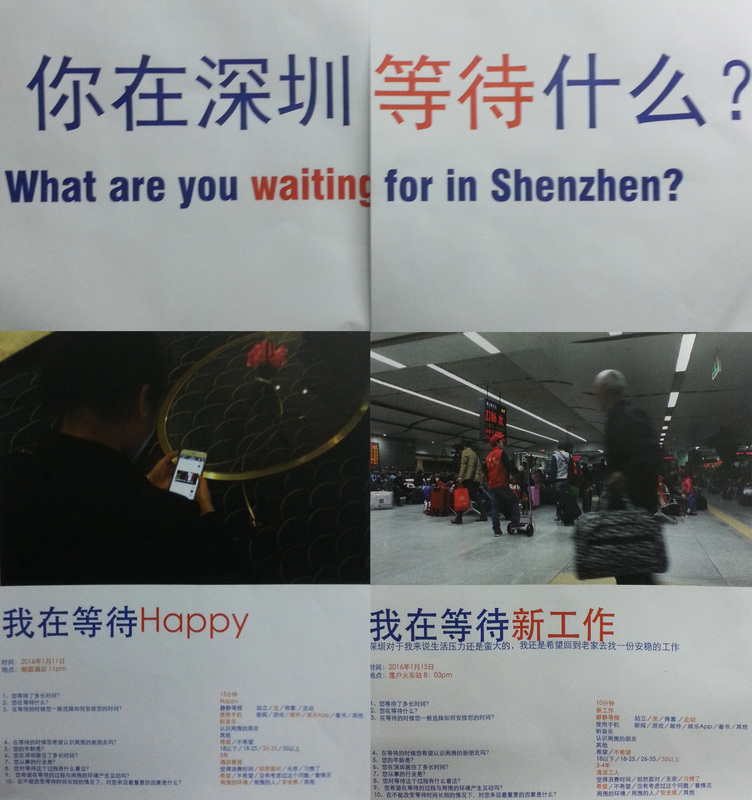

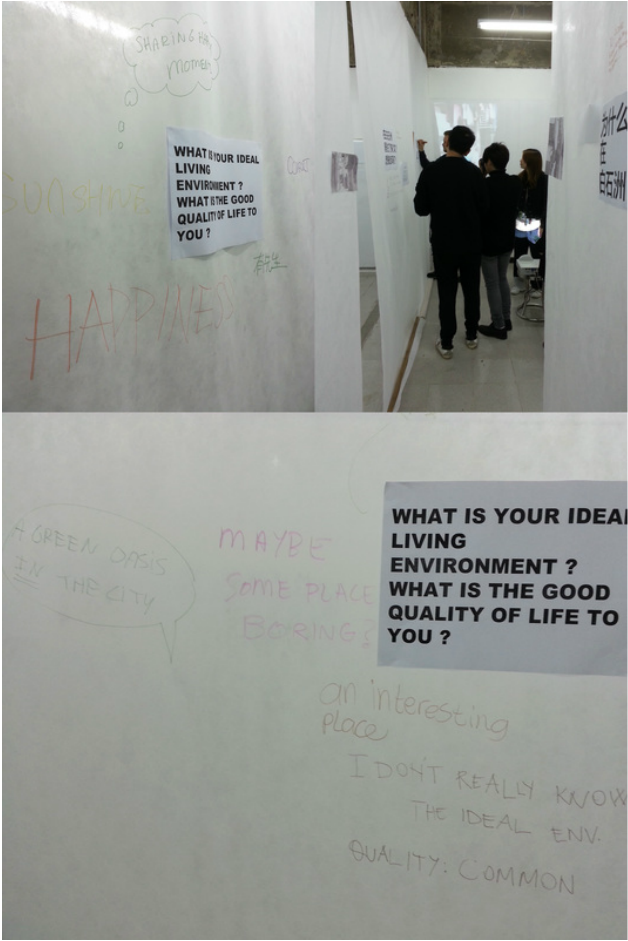

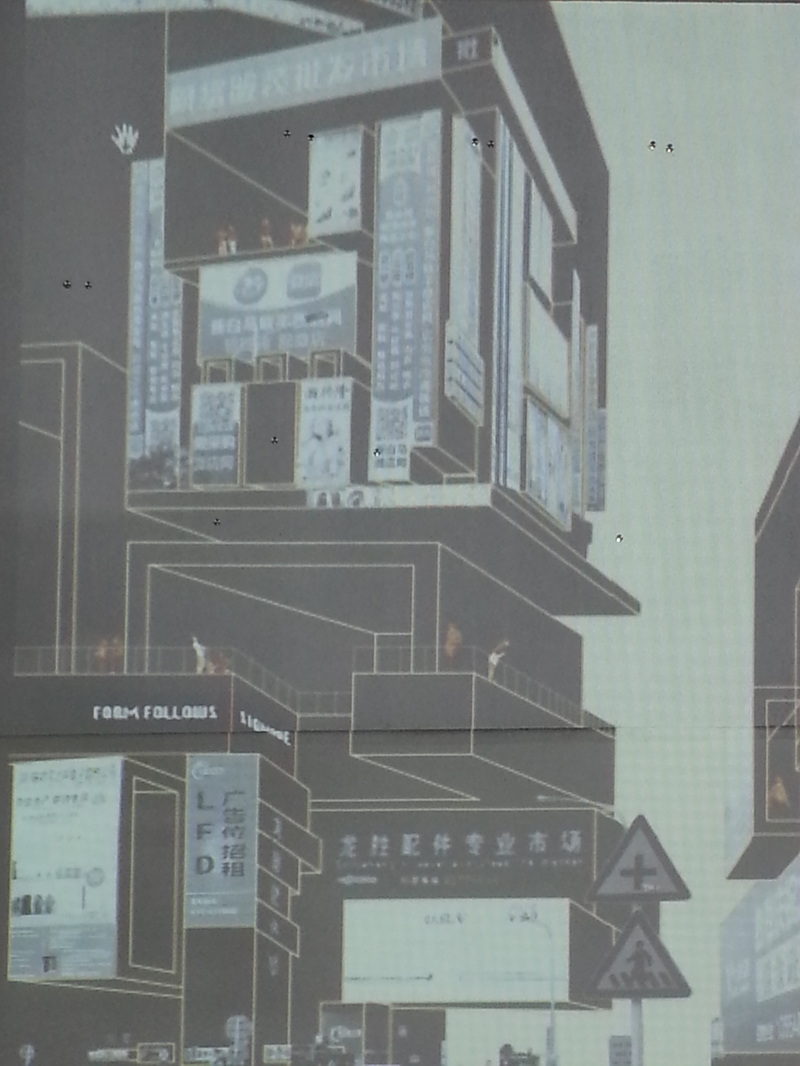

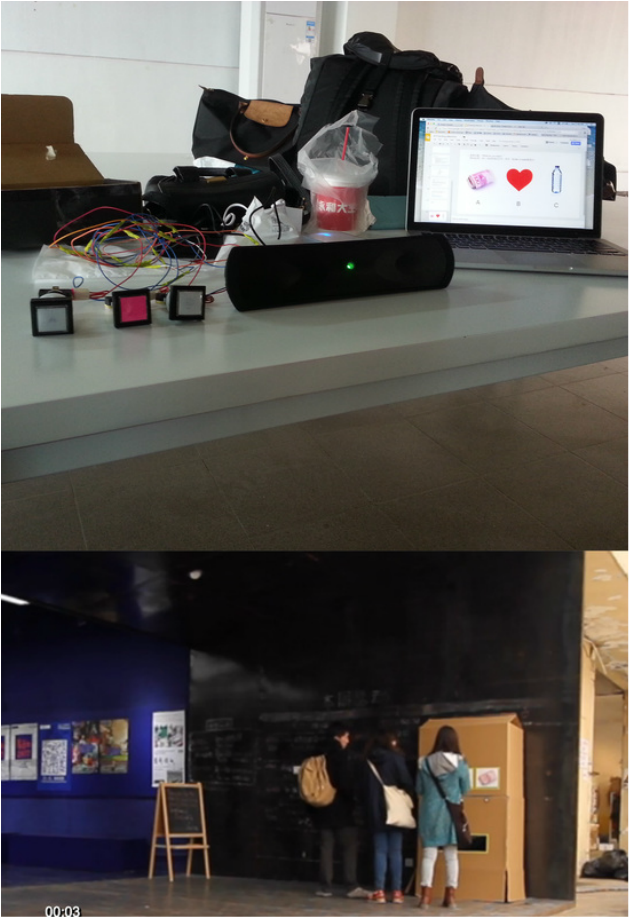

“A plan or drawing produced to show the look and function or workings of a building, garment, or other object before it is built or made” and to design is to “Do or plan (something) with a specific purpose or intention in mind.” (Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/design) A designer is therefore someone who does or plans “(something) with a specific purpose or intention in mind.” From a non-Western perspective, designer can also be called a 意匠 (Yi Jiang) The character 意, for example, carries multiple meanings- as consciousness, meaning, intention, significance, idea, sense, desire, thought and longing. As 意匠, a designer is a craftsman who shapes our consciousness and produces meaning. Through the designer’s work, our sense of the world is heightened, and the quotidian elevated to a level of significance. A designer also shapes our desires and longings. Our yearnings for homeland, justice, freedom or luxury are given material form. 意 is also made up of several ideograms- {sound (音 Ying)}, {heart (心 Xing)}, {stand, establish or set (立 Li)}, and {day, daily or sun (日 Re)}. On the other hand, 匠 or craftsman consists of 2 ideograms- 匚 (Fang), which means a box, and 斤 (Jin), which is an axe. The combinatory meanings of 意匠, from the elemental to the extended meanings offer a much more expanded role that a designer can take in contemporary society. First and foremost, a designer needs to be attentive to sound (音 Ying) in the design process. It refutes the primacy of the visual, especially when the design process is much more screen-based now. From (心 Xing), we know passion, generosity, emotion and empathy are as important as skills and techniques, while (立 Li) suggests that design is a setting in place, whether the outcome is a piece of furniture, a book or a neighborhood. (日 Re) reminds us that as a designer, we need daily devotion and a dedication to the continuing refinement and learning of our craft. Our tools, 斤 (Jin) are housed in a box that affords mobility. It echoes how our hypermobility of ideas, people and finances in the 21st century has given rise to a globally situated design practice. Learning from Shenzhen: The City as a Studio, was conceived and led by Thomas Kong. It formed part of a series of studios organized by the Aformal Academy during the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture. In this 5-day studio, participants were involved in a number of micro, on-site investigations centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in China’s first Special Economic Zone. Waiting Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work. Uniform The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority. Good life Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond. Form follows signage Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage. Shenzhen Vending Machine Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, the body and human relationship. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired. Drawing Memories

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life. The invitation from the Aformal Academy to teach a class during the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture in Shenzhen, China was a pleasant surprise and a serendipitous meeting of distant minds. I have just written a proposal for a fictitious design school that aimed to reimagine the current institutionalized structure and organization of the architecture and design education. The proposal was motivated by my desire to search for an alternative design pedagogy less organized around the long cherished model of a design studio housed in a school and be more engaged in a peripatetic experience situated within multiple locales in the city. The biennale in Shenzhen offered a wonderful opportunity to undertake such a pedagogical experiment. Titled, Relearning, the Biennale hopes to question the basic assumptions of the architectural artifact, design of cities and by extension their impacts on our everyday lives.

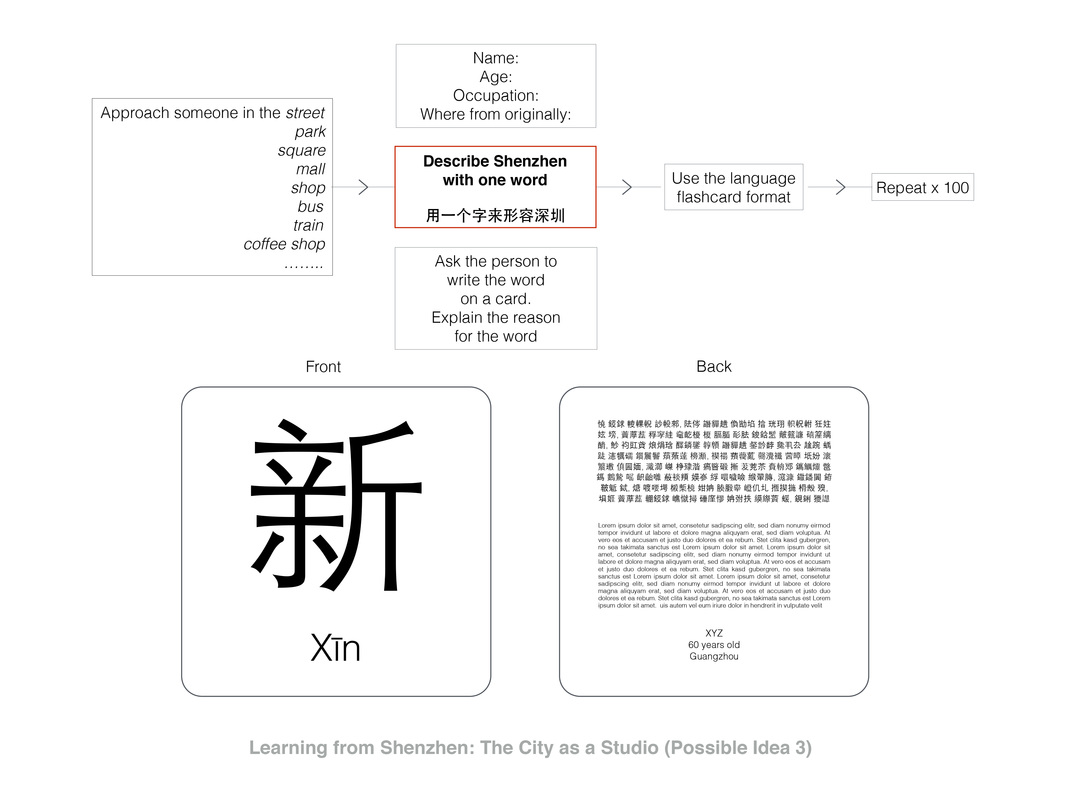

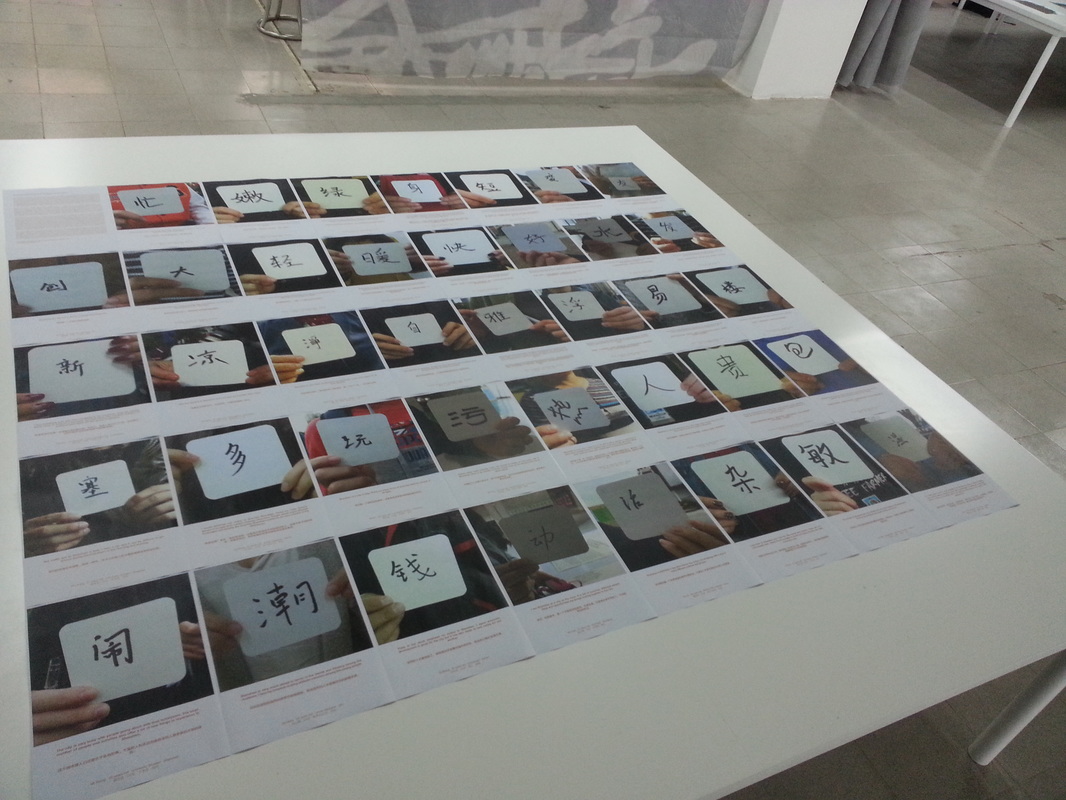

Much has been written about the meteoric rise of Shenzhen from a quiet fishing village to a modern metropolis after it was decreed by the late premier Deng Xiaoping as a Special Economic Zone. The multitudes of social, cultural, economical and environmental challenges that accompany such an accelerated urbanization process are also well documented. What more can we learn from Shenzhen? And who else can we learn from besides the mélange of professionals, experts, city officials, thinkers and observers of Chinese cities? In the spirit of RElearning, RE not in the Greek god Sisyphus’s sense of repetitive actions condemned to eternal futility, but one that could refresh and redirect our learning of Shenzhen. The Shenzhen Flash Cards Project carries such an aspiration. The RElearning happens at street-level and from the local residents through the process of crowd sourcing a Chinese character or字that best exemplifies the city at this particular point in time. The hand written character will be recorded on a flash card and the process repeated. The final collection of flash cards will consist of the accumulated handwritten cards over time. As a system of pictograms and ideograms, the Chinese language is most suited to this pedagogical experiment. The compositional meanings inherent in a Chinese character and its combinatory possibilities expand on what could first be perceived as a limited and narrow beginning. Like the use of flash cards to learn a new language, the city flash cards will hopefully offer multiple, drifting, colliding, commingling and shifting meanings of Shenzhen shaped by the forces of urbanization and globalization. The RElearning of the city through the Shenzhen Flash Cards Project does not proceed from a fully formed theory or will the eventual understanding be systematic, complete and unified. Rather the learner needs to interpret and filter a palimpsest of dreams, desires, fears and memories, which defies neat categorization and are ultimately fragmentary. In a sense, this is how a city appears to us and is experienced. It is conceived that the flash cards will have educational, economic and cultural afterlives beyond the Biennale. It could be used by schoolteachers to cultivate awareness among Shenzhen students the manifold values and perceptions of a diverse group of city dwellers. It could be sold as a memento in a gift shop, which offers visitors to Shenzhen something beyond a packaged touristic experience. It could also be housed in the library as an archival material for future learning and reference. Or it could simply remain on the shelf of an academic, tucked among an assortment of books, papers and other personal objects, to be rediscovered only after several years have passed. Sunlight filters through the door

Sunlight lights up the inside of the door The sun is captured by the door Each day starts with an opened door The door leaks in the light The door locks in the light The door is illuminated There is a ray of light in every door The door protects each day The door lets in the day The door lets in the sun The light is in the middle of the door Consciousness is a matter of the heart One needs to be attentive to feel the light A standing person who lets the light into his heart One needs to be attentive and has heart One feels each day with attention Standing above the light, one feels with the heart Standing above the light, one's heart is illuminated Standing attentive each day to reach illumination Standing each day is good for the heart An attentive heart feels the light An attentive heart lets the light in An attentive heart is led by the light The light opens up the attentive heart One needs to be attentive to what the heart feels Light illuminates the attentive heart Light fills an attentive heart Light bridges attention and heart The heart illuminates those who stand |

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed