|

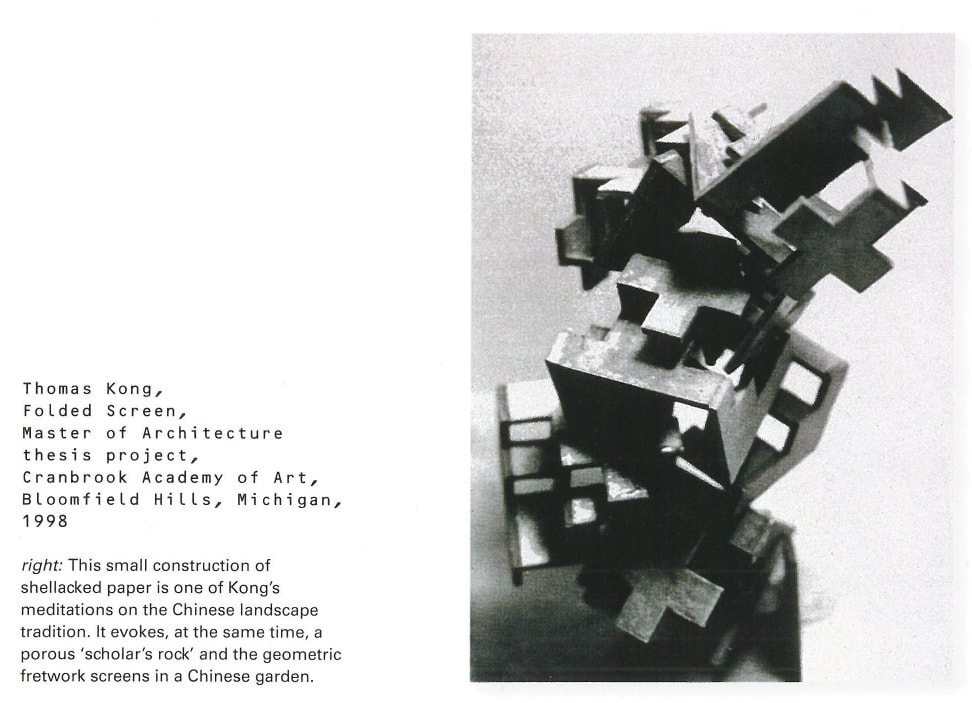

I am honoured to have my work featured by Cranbrook Academy of Art Artist-in-Residence Peter Lynch in the recent issue of Architecture Design.

Architecture is a technical solution to problems that are not technical at all. Mark Wigley.

Architecture has emerged in the public's consciousness in recent years, with architects portrayed by the media as cultural shapers and movers in society. American architect Elizabeth Diller, partner of New York practice Diller+Scofidio Renfro was listed as one of Times magazine's 100 most influential personalities of 2018 while the globe-trotting Danish architect Bjarke Ingels is regularly featured on CNN expounding his design ideas and projects. On the other hand, cities are hastily organizing architecture biennials and triennials with the hope of projecting their cultural capital to an international audience. There are a total of 34 biennials and triennials globally, with 22 being hosted in different cities concurrently the same year. The Venice Biennial, the oldest and most renowned among the biennials saw over 60,000 visitors in just the first three weeks alone in 2016. The final total number of visitors was 260,000, which was a record for the biennial. Politicians, policymakers and brand consultants are quick to seize on the promotion of culture in enhancing liveability, to attract global talent, tourists and increase economic competitiveness, It is a narrow yet alluring definition of culture that is perceived to boost a city's spot in the annual global city ranking exercise. This is not surprising. As cultural artifacts, buildings carry strong cultural currents in our built environment. They reflect the values, beliefs, and customs of a society at a particular point in time.

The word culture has its origin from the Latin word cultura, which means 'to grow,' to 'cultivate.' In Biology, culture refers to the growth of bacteria and cells by providing the right mix of nutrients and conditions. Whether it is the growth of bacteria in a petri dish or the cultivation of culture in society, time, patience, care, commitment, attention, and nourishment are needed to allow something to come into existence. It is an emplaced process, bounded loosely in a locale or within the glass confines of a petri dish. In his 1958 essay, Culture is Ordinary, Raymond Williams bemoaned the association of culture only with the high culture of the arts like literature, painting, dance, and theatre. To be cultured means having a taste for the finer things as opposed to a low culture, which belongs to the masses. Williams argued that both high and low cultures coexist in our lives, and we should instead be looking at culture as a 'whole way of life.' In other words, our everyday existence, in which we engage in myriad forms of daily activities, interact with people from different walks of life and in spaces that are both ordinary and exquisite. Although written in 1958, it still serves an important reminder to architects and architecture students. As spatial designers who can influence behaviors and actions, and modulate perceptions through our design, we, too, must be mindful of the manifold and sometimes competing cultures commingling amongst us. It is especially critical at a time when increasing socio-economic inequality frustrates, excludes and divides society, and the rising voices of underrepresented communities who demand to be heard. First. A true story- The director of a global, multidisciplinary design firm based in London was asked, "What do you look for in a new employee?". His reply, "Perhaps a sense of humor?"

Graduating students take note. His reply seems flippant and perhaps irresponsible. Having taught at SAIC, a private art and design school for over 12 years, that was certainly my first reaction. Out of curiosity, I Googled "Why a sense of humor is important?" and found 288 direct links out of 113,000,000 results (in 0.45 seconds). The positive impact of humor on personal relationships, emotional wellbeing, in the workplace, and in businesses is astonishing and offers a moment of reflection for me. It parallels the debate between the two central characters over laughter in the novel "The Name of the Rose," by Umberto Eco. Set in the Middle Ages, William of Baskerville, a Franciscan monk argues for careful deliberation and interpretation while Jorge de Burgos, the elderly and blind monk from the abbey harbors deep suspicions about laughter. To him, laughter is diabolical, subversive. It reduces the serious learning of the monks to triviality and farce. Laughter destabilizes and erodes the status quo. Jorge de Burgos, therefore, sees it as his sacred duty, to the point of committing murders and burning the library (apologies for the spoiler) to protect the established, divine order before it descends into anarchy. We are witnessing a profound shift at all levels of society that will significantly impact lives on the planet, and a new order is taking shape. Received notions of identity, belonging, ownership, access, and control are questioned and subjected to a re-examination in our current social, political and technological milieu. Architecture as built culture is not immune to scrutiny. The thesis projects of the Class of 2019 bear testament to such scrutiny. The students know where they stand in the debate between William of Baskerville and Jorge de Burgos. They are not cowed by fear or anxiety, nor are they resigned to the present state of affairs. Their projects offer a glimpse of certain possibilities at a time of transition and uncertainty; personal declarations forged and materialized over two semesters of conversation, debate, research, drawing, testing, and making. They invite us to share their defiance, hope, ambition, curiosity, imagination, and resilience. I would add a sense of humor to the mix. Unlike the misplaced aversion to laughter by the zealot Jorge de Burgos, it is an invaluable tool that builds conviviality, breaks down tribal instincts, crushes the climate of fear, disarms a tense situation and bridges differences. Or as the irrepressible John Cleese, one of the founding members of the Monty Python comedy group once said, "Laughter is the force of democracy." May the graduating 2019 class of the Master of Architecture and the Master of Architecture (With an Emphasis in Interior Architecture) finds fulfillment, success, and brings forth joy and laughter through their work. I visited Tadao Ando's Church of Light in Ibaraki, Japan, many years ago and found this slide as I was packing my library. I recall I was alone in the church and taking pictures of the interior and the furniture. When I turned around, I saw a beam of light streaming from the cross-shaped opening on the end wall. It went across the floor, up onto the pulpit, and over an opened bible.

In 2009, I received the Japp Bakema Fellowship from the Netherlands Architecture Institute for my project ZERO. It was the height of the Great Recession and architects were laid off by the droves daily in Chicago. My architecture students who recently graduated were unable to find work or had to take up odd jobs to make ends meet. As an architect and a teacher, I came to realize the limitation of an architectural education that resides within an academy and cut off from the larger society, which architecture students will eventually be part of. I was dismayed by the narrow definition of architecture, the limited contributions of an architect besides a building, and the traditional client-architect relationship in practice. I saw the Great Recession as an opportunity to re-evaluate and re-frame architecture education and the role of an architect in society.

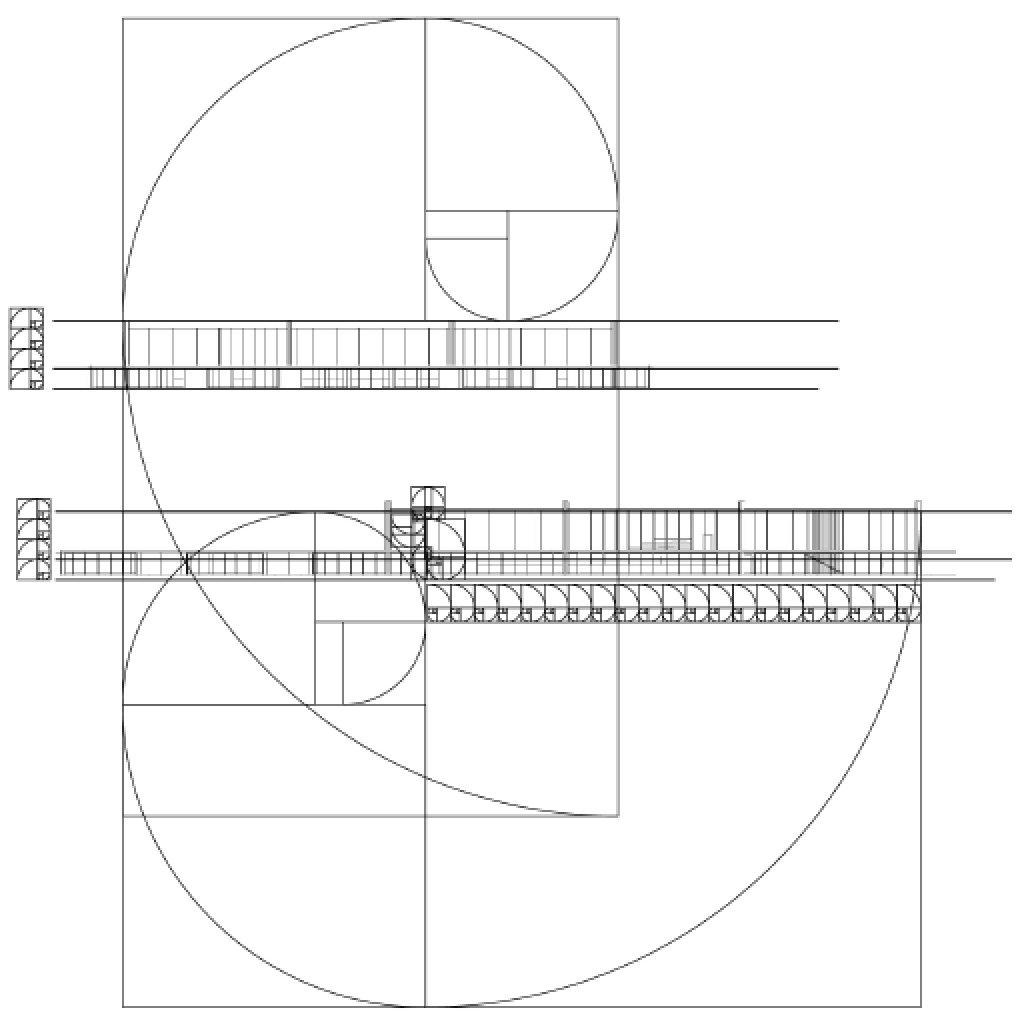

The fellowship afforded me the financial resources and time to research and document the various manifestations, causes, and meanings of emptiness, the values of unbuilding and how the local residents in Asian cities, many who were living along the margins of society, were able to occupy empty spaces for different durations and for social, commercial and personal uses. It opened my eyes to their ingenious, opportunistic, and informal use of empty spaces, found materials and urban infrastructures to fulfill their daily needs. Through ZERO, I discovered the relational dynamics of their occupations and actions, which were attributed to their creative use of scarce resources, and their ability to adapt, negotiate and utilize social relationships and existing spatial contexts to their advantage. Their occupation tactics were both a form of resistance and an adaptation to the planned spaces in the cities. I was fascinated by the spatial intelligence and material resourcefulness of the residents despite not receiving any formal design education. Its radical design amateurism and material relativism driven largely by pure purpose and need challenged what I learned in architecture school and the canons of good design. ZERO discovered the under and unrepresented everyday beauty and the potentiality of society’s detritus, be it material, social, cultural or spatial. The casual juxtaposition of the planned and spontaneous, the new and the discarded questioned our conventional notion of authenticity. The creative re-using of cast-off objects and materials by the residents was also a consoling knowledge in an age of throw-aways. ZERO was a timely springboard for my own search for an alternative design education and practice at a time of economic crisis, as well to broaden what an architect can contribute to society besides another building in a post-economic bubble age. Ceil Balmond, OBE spoke of structures as the 'punctuation of space, episodic and rhythmic'. It's not unlike how a poorly placed period or comma in a sentence can ruin a sense of gravity or lightness. His way of looking at structures re-establishes the relationship between structures and life- with the breathing, living and rhythmic body.

My 5 min presentation for the event on Sep 16, 2017 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

The airport fascinates me as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Seldom do you find gathered in a building such a diversity of nationalities and cultures. In this slide, you see the Goddess of the Sea, Mazu and her 2 Heavenly assistants taking a business class flight from China to Malaysia for a religious event. They were issued boarding passes too. Future innovations will need to recognize and address the needs and experiences of a diverse group of travelers and users. In Singapore, the Changi Airport is a destination for the young and old who come to the airport for a variety of reasons. So much so that Changi may be the only airport that has so many signs discouraging students from studying. Changi is more than just an airport to the locals. It is a third place, a term coined by Ray Oldenburg to describe a place that people gather that is neither a home nor the office. First impressions count. The Copenhagen Airport is a showcase of Danish design. On the other hand, during the design of the Changi Airport in the 1970s, the Prime Minister then instructed the planners to plant rows of rain and palm trees along the highway leading from the airport to the city center, and that they be well maintained, for 2 reasons. First, it conveyed to arriving visitors that this is the tropics, and secondly, a signal to potential foreign investors that the city-state is well managed and the right place to invest their money in. This first impression was designed to reach a high point when the towers of capitalism, hidden by the trees, unfolded before your eyes as you reached the highest point of the Benjamin Sheares bridge after a 15 min taxi ride from the airport. Vice versa, the experience of the airport starts before arriving at the terminal. The in-town check-in service in Hong Kong is a good example. It gives back some control of time to the travelers who have to negotiate an environment that encourages consumption yet tightly controlled and surveilled. I believe designing the experience before and after the airport is as important as the airport itself. "My work depends on engineers, on electricians, and on a number of other specialists. And, in my office, I have more than twenty-five architects, so it's not very solitary. But, periodically, during the process of a project, I take home the drawings and I need to concentrate not only on designing and sketching things, but on really knowing the building, really knowing the project. I have to be able to walk through the whole building mentally without looking at the drawings, you know? I have to be able to sit and imagine walking through the building, going down each hall, entering the bathroom, washing my hands, going to the kitchen if it is a house. And if it is a public building, this can indeed be difficult. But I make every effort to study the project as it develops. Only when you can walk mentally through the building can you design the final details and can you feel the atmosphere of that building and what it really means. For this, I need moments to concentrate by myself, alone. In the office, this is not too easy because there are telephones, visitors-and interviews. But I can go home and sit alone and reflect."

Alvaro Siza Vieira. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.artic.edu/docview/1874001408?pq-origsite=summon "As much as poetry and literature, architecture is about relations between things and about passages from one to the other."

Alvaro Siza Vieira. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.artic.edu/docview/1874001408?pq-origsite=summon "Architecture is the revelation of the hazely latent, collective desire. This cannot be taught but it is possible to learn to desire it." Alvaro Siza.

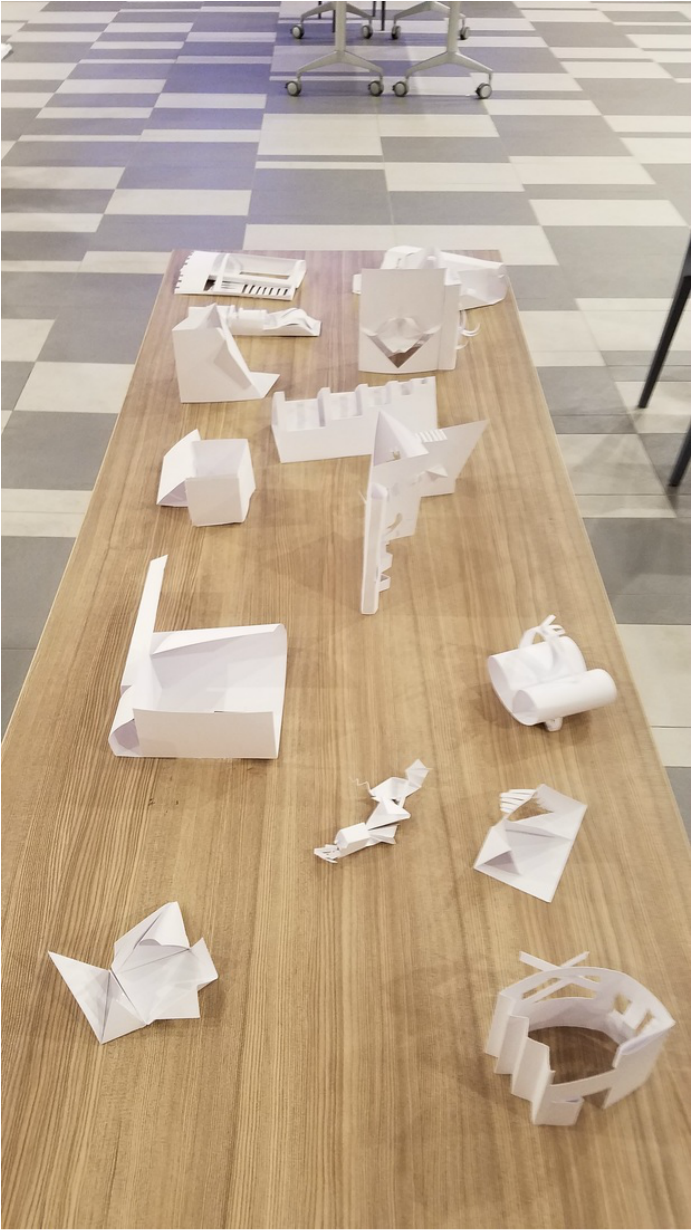

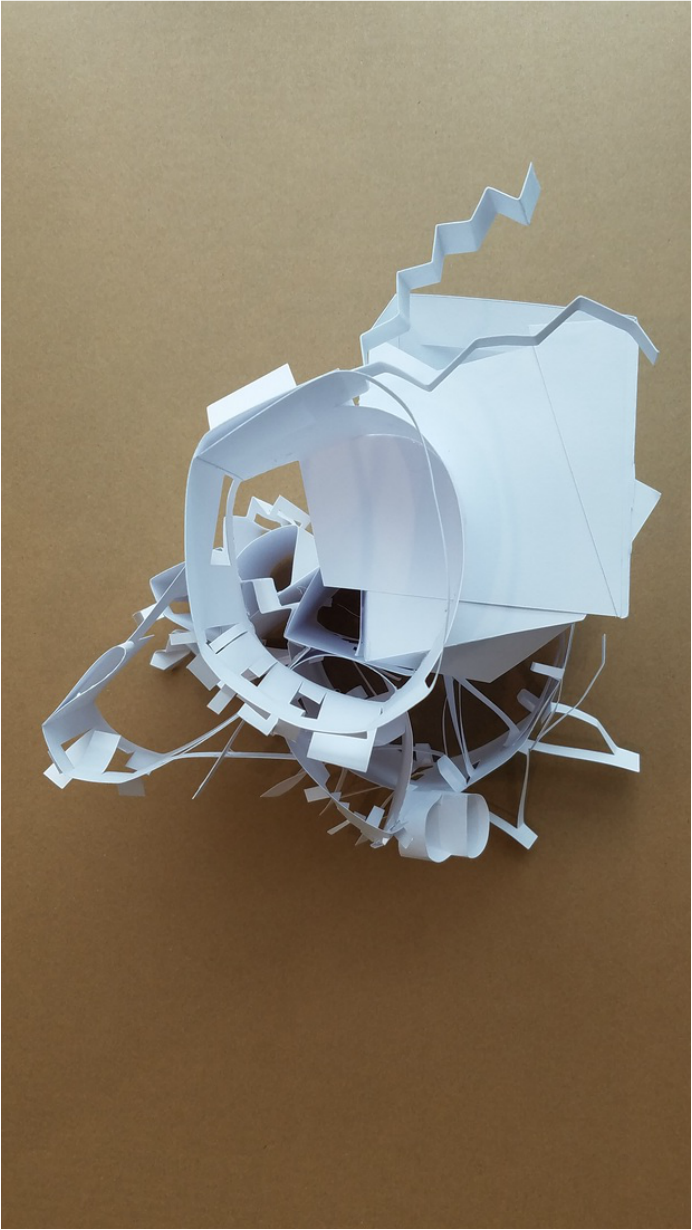

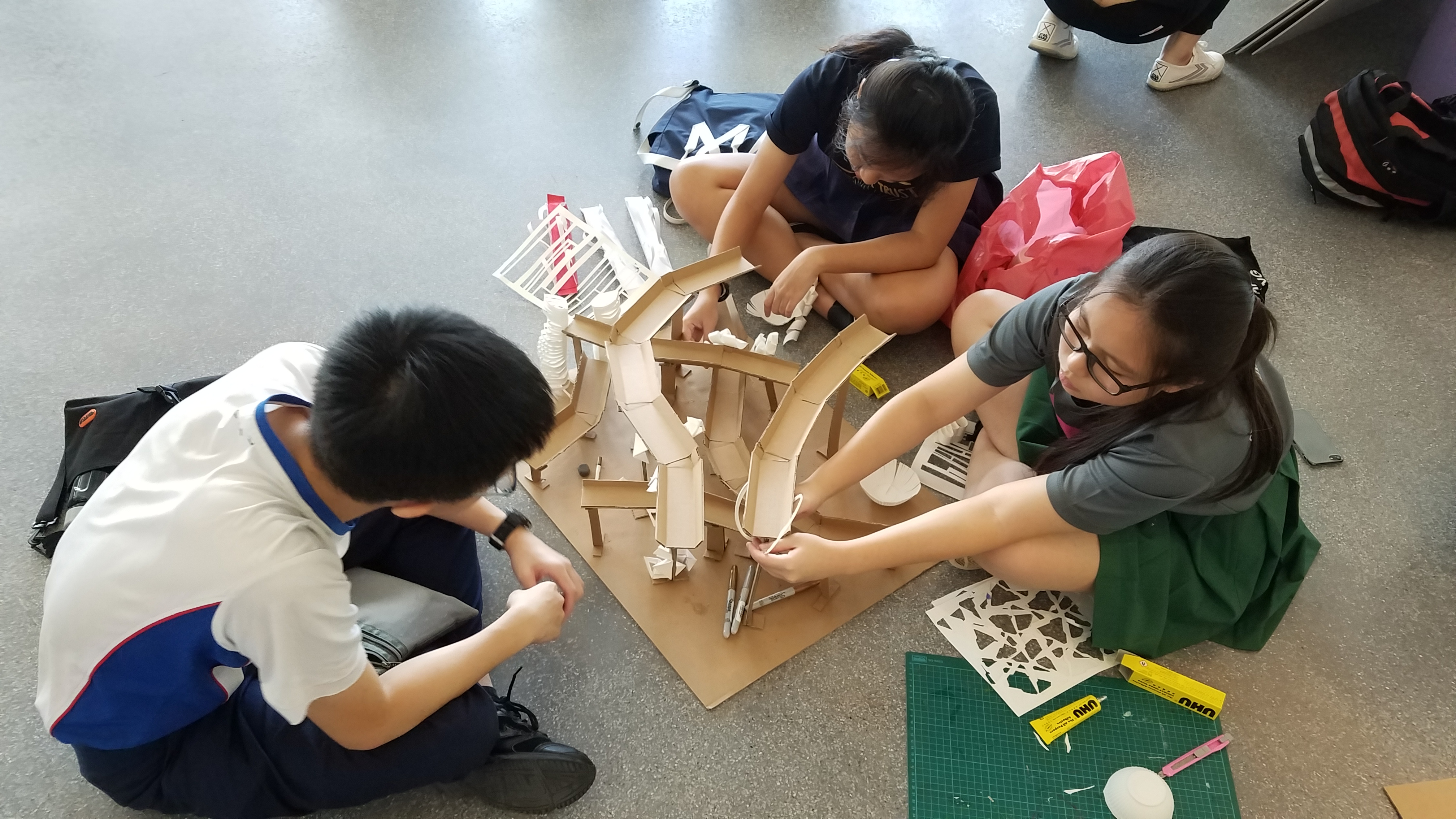

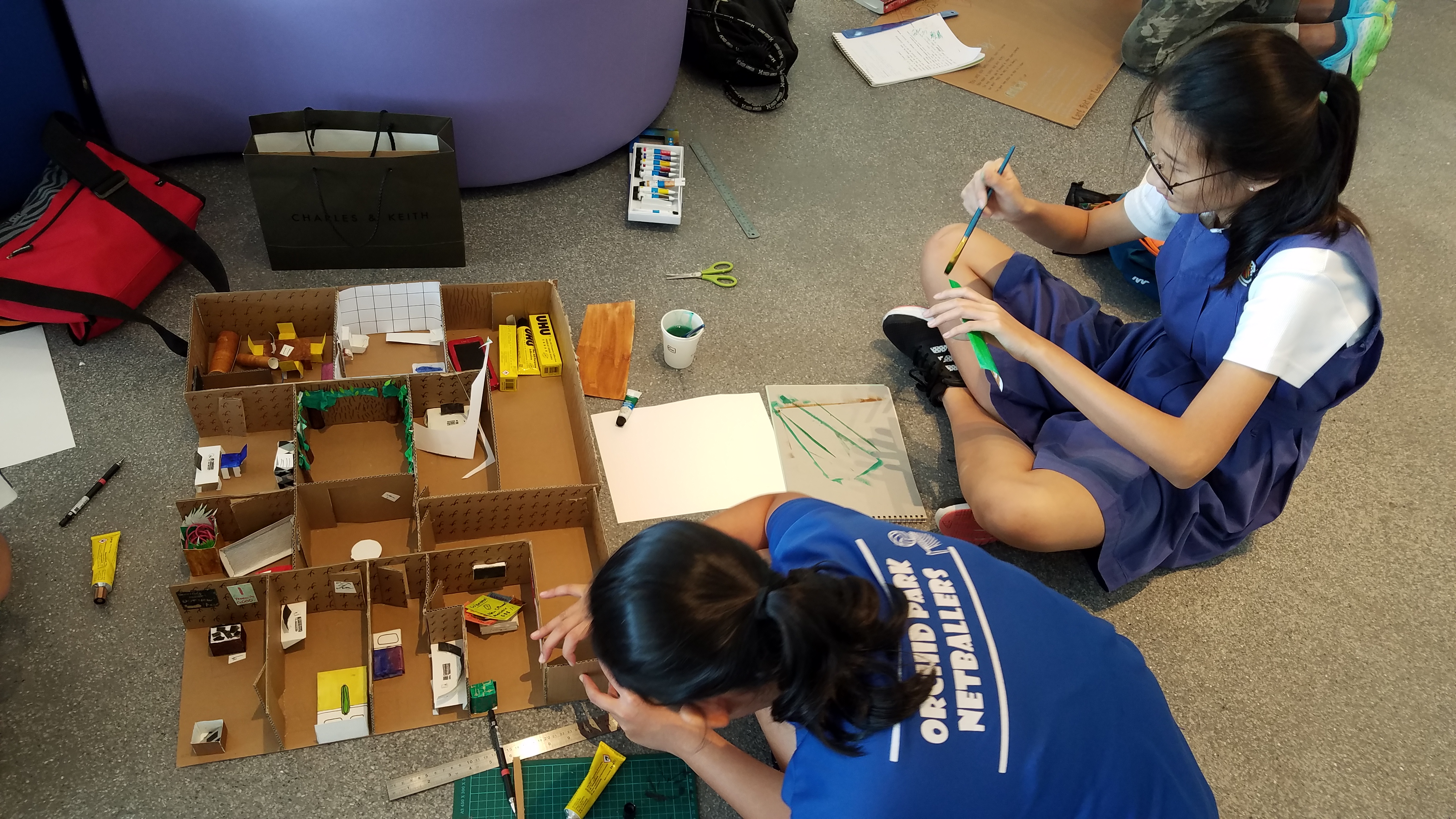

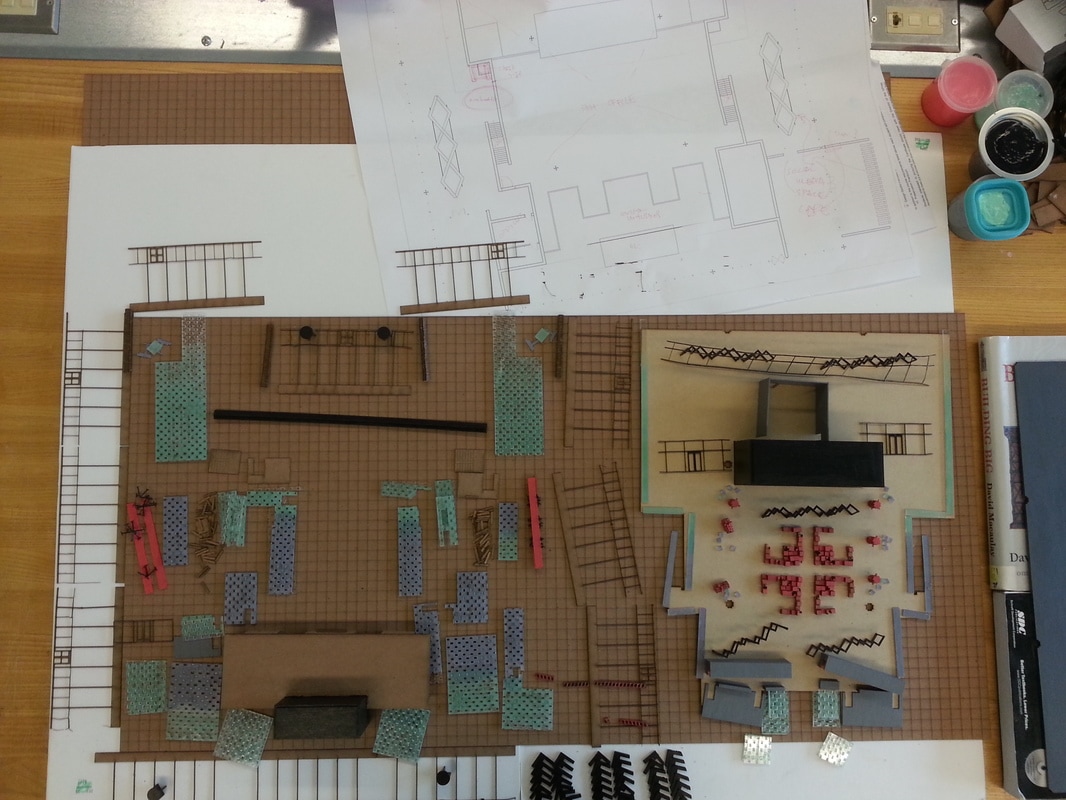

I was a mentor to a group of high school art students for over 5 days. Working collaboratively on a theme set by Singapore's Ministry of Education, the students developed spatial propositions via models and drawings. A showcase of the works was held on the last day.

The energy and enthusiasm was infectious. The works carried a spirit of shear audacity that defied my expectations. What to make of a web of bridges that dared to confront our discriminating mind? Who wouldn't want to be in a place of peace and tranquility amidst a sea of noise and distraction? Or be thrown into a reality gameshow that do not simplify our desire for and repulsion of digital connection? And not to forget a tower that fostered sociability over coffee, gardening and a good book. Countless ideas and possibilities to keep us curious, engaged and inspired! “Art and Design should not only be an object but an excuse for a dialogue.” Douglas Gordon and Thomas Kong

“When a person or a building disappears, everything becomes impregnated with that person's or building’s presence. Every single object as well as every space becomes a reminder of absence, as if absence were more important than presence.” Doris Salcedo and Thomas Kong “In art and design, everything is particular. The more particular and the more intimate you get, the more you can give in the piece.” Doris Salcedo and Thomas Kong “I'm often asked the same question: What in your work comes from your own culture? As if I have a recipe and I can actually isolate the Arab or Asian ingredient, the woman or man ingredient, the Palestinian or Singaporean ingredient. People often expect tidy definitions of otherness, as if identity is something fixed and easily definable.” Mona Hatoum and Thomas Kong “Every day, we came to [the exhibition space] to work together. We continued to organise these things and spaces. So actually, this exhibition is not about displaying, but about organizing spaces. Song Dong and Thomas Kong “The process of living and the process of thinking and perceiving the world happen in everyday life. I’ve found that sometimes the studio is an isolated place, an artificial place like a bubble – a bubble in which the artist and designer is by himself or herself, thinking about himself or herself. It becomes too grand a space. What happens when you don’t have a studio is that you have to be confronted with reality all the time.” Gabriel Orozco and Thomas Kong “I always want to design a frame or a building or structure that can be open to everybody.” Ai Weiwei and Thomas Kong “Designing and Architecture is not a profession, it is an attitude.” László Moholy-Nagy and Thomas Kong “An artist and a designer must constantly be faced with new and always different problems.” Cai Guo Qiang and Thomas Kong “Many artists and architects try to construct a world for themselves: from concept to format. From knowledge to inspiration, from a methodology to learn about, and to express the world.” Cai Guo Qiang and Thomas Kong “Caress the detail, the divine design detail.” Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong “Artists and designers themselves are not confined, but their output is.” Robert Smithson and Thomas Kong “Here is what we have to offer you in its most elaborate form in graduate advising -- confusion guided by a clear sense of purpose.” Gordon Matta Clark and Thomas Kong “A novelist and an architect are, like all mortals, more fully at home on the surface of the present than in the ooze of the past.” Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong Life or a building is a great sunrise. I do not see why death and unbuilding should not be an even greater one. Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong The pages and spaces are still blank, but there is a miraculous feeling of the words and lives being there, written in invisible ink and clamoring to become visible. Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong It ought to make us feel ashamed when we talk like we know what we’re talking about when we talk about love and design. Raymond Carver and Thomas Kong You’ve got to work with your mistakes and intuitions until they look intended. Understand? Raymond Carver and Thomas Kong If you only read the design books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong I dream and design. Sometimes I think that’s the only right thing to do. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong Death or unbuilding is not the opposite of life or building, but a part of it. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong Retrieved from: http://archnet.org/system/publications/contents/4765/original/DPC1477.pdf?1384786653

Francois Laplantine’s book The Life of the Senses debunks the myth of Western rationality and category thinking. Instead, he argues for a life that is enmeshed in the flow of our senses, which defies neat compartmentalizing. What is the implication for spatial and object designers, and those who teach design? How can we breakdown the silos of learning, and take up the challenge and the opportunities that a life fully engaged in the senses bring? He wrote,

“ Category thinking eschews that which is formed in crossings, transitions, unstable and ephemeral movements of oscillation. It opts, in a drastic manner, for the fixity of time, movement and the multiple, and opposes, in so doing, the tension of the between and the in-between. Yet, these exist. Between presence and absence, there is melancholy and its Lusitanian inflection that bears the name saudade. Between darkness and light, there is chiaroscuro. Between the retracted and the rolled out, there is the movement of loosening. Between wakefulness and dreaming, there is dreaminess. Between the expected and the unforeseen, the suspected. Between trust and mistrust, the slight doubt. Between the certainty of that which is named and the designated (the definition) and refusal to speak is that which can be suggested (Mallarmé) or shown (Wittgenstein). Between life and death, there is the spectral: ghosts, or as thry say in Haiti, Zombies, revenants as well as survivors.” The late New York Times journalist David Carr used the term Present Future to describe the state of journalism in the 21st century, where the present proliferation of news feeds that cater to a multitude of readers at this moment does not necessarily lead to a definitive, clear idea of what journalism will become in the future. Nonetheless, the future is slowly being shaped by these current developments and one should not shy away from them or be overly nostalgic with the past. Perhaps one can say the same for the future of architectural education and the practice of architecture? It is often convenient and easy to project a future scenario that celebrates technology (usually) and how it will herald a radical shift in the conceptualization, design, making and habitation of architectural spaces. However, we are also living in the present while making these projections; going through the daily mundane but necessary rituals that sustain our everyday life. The body we carry with us still retains the memories of thousands of years of evolution despite their continuing tempering by new technologies. Cultural background too, influences our disposition towards new ideas and discoveries, which affects how fast the future becomes the present. By retaining the present with the future is a wise and prudent step in our desire to discover what lies beyond the horizon.

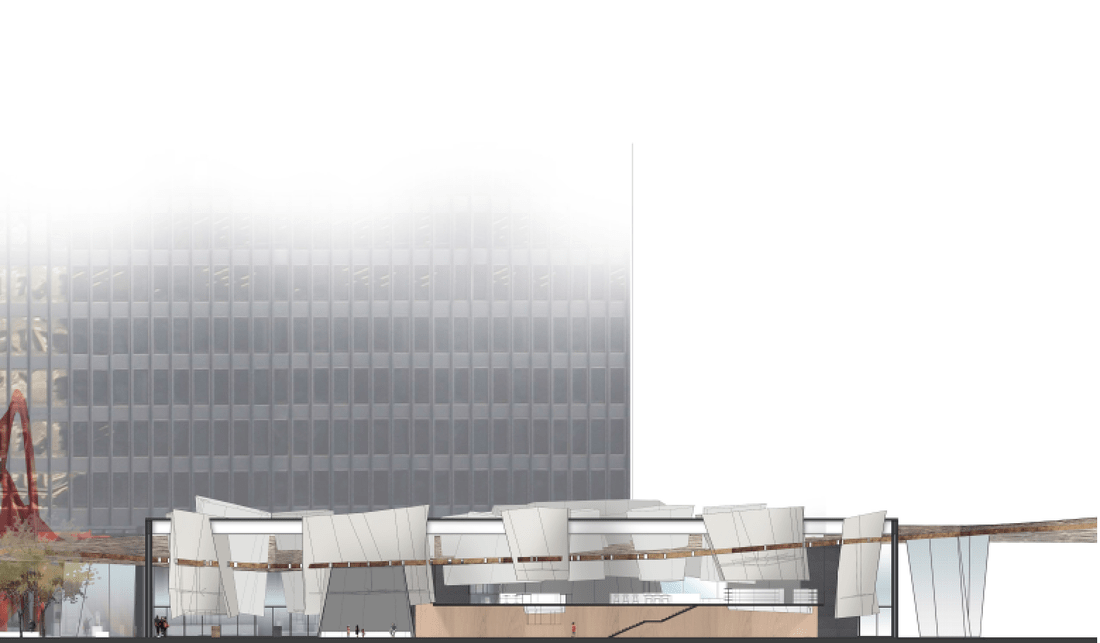

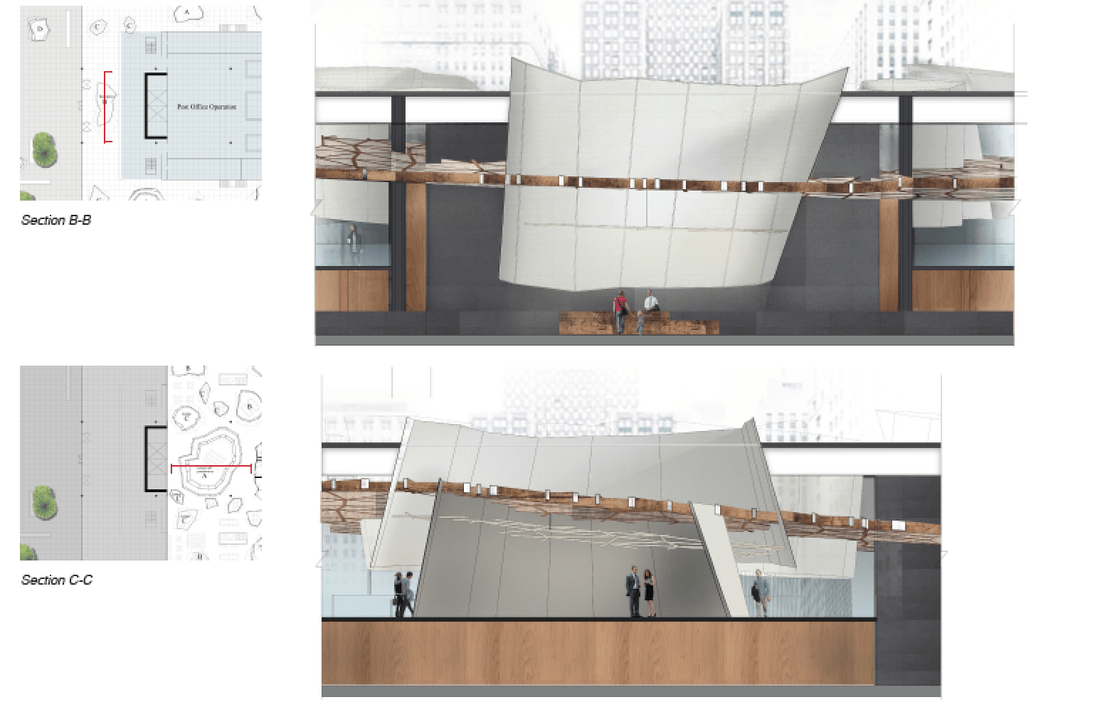

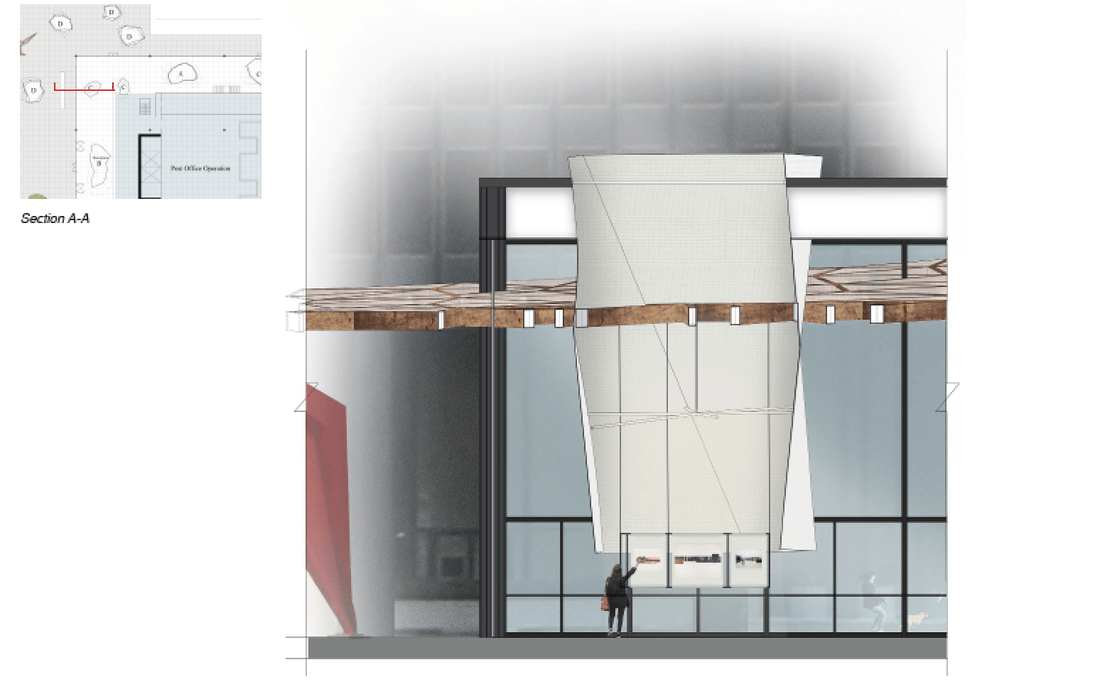

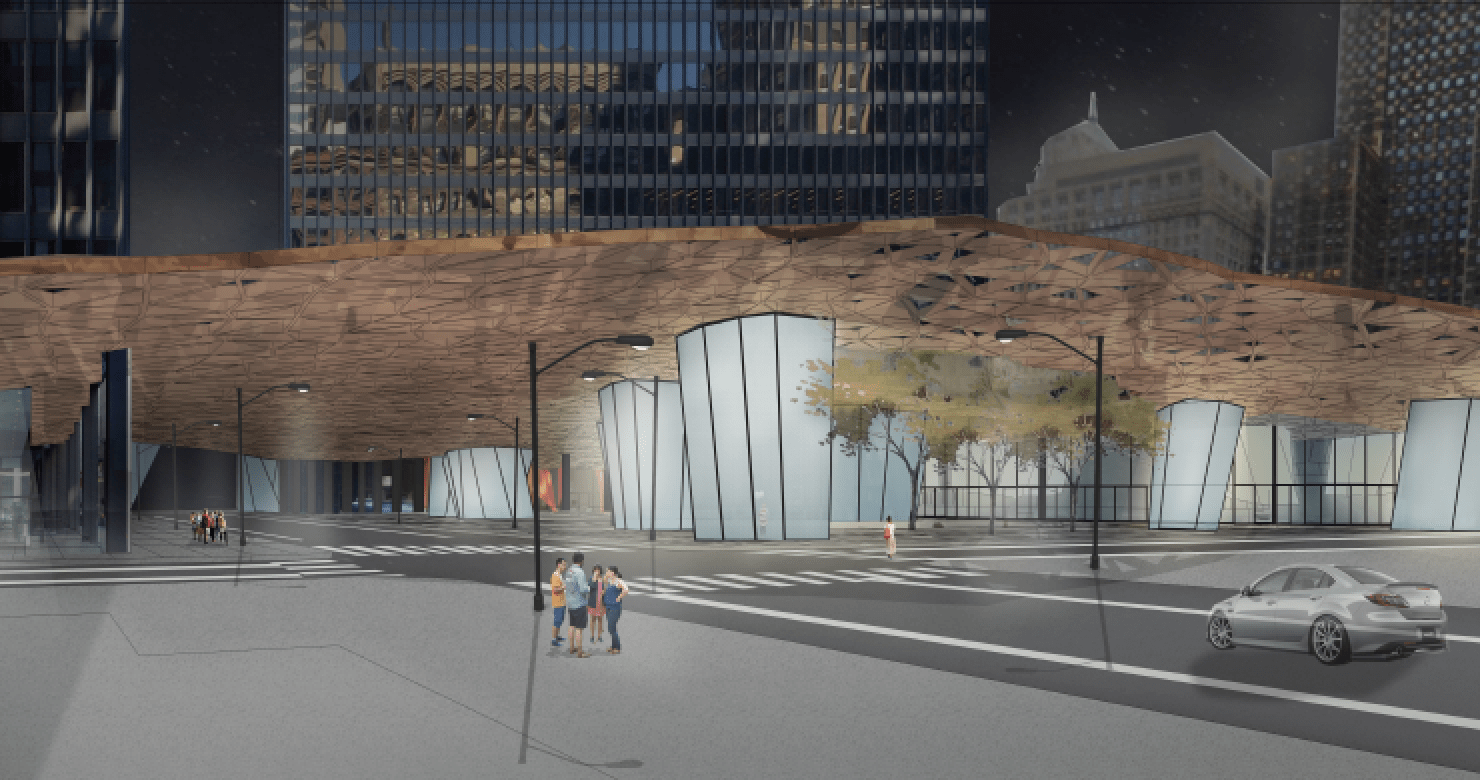

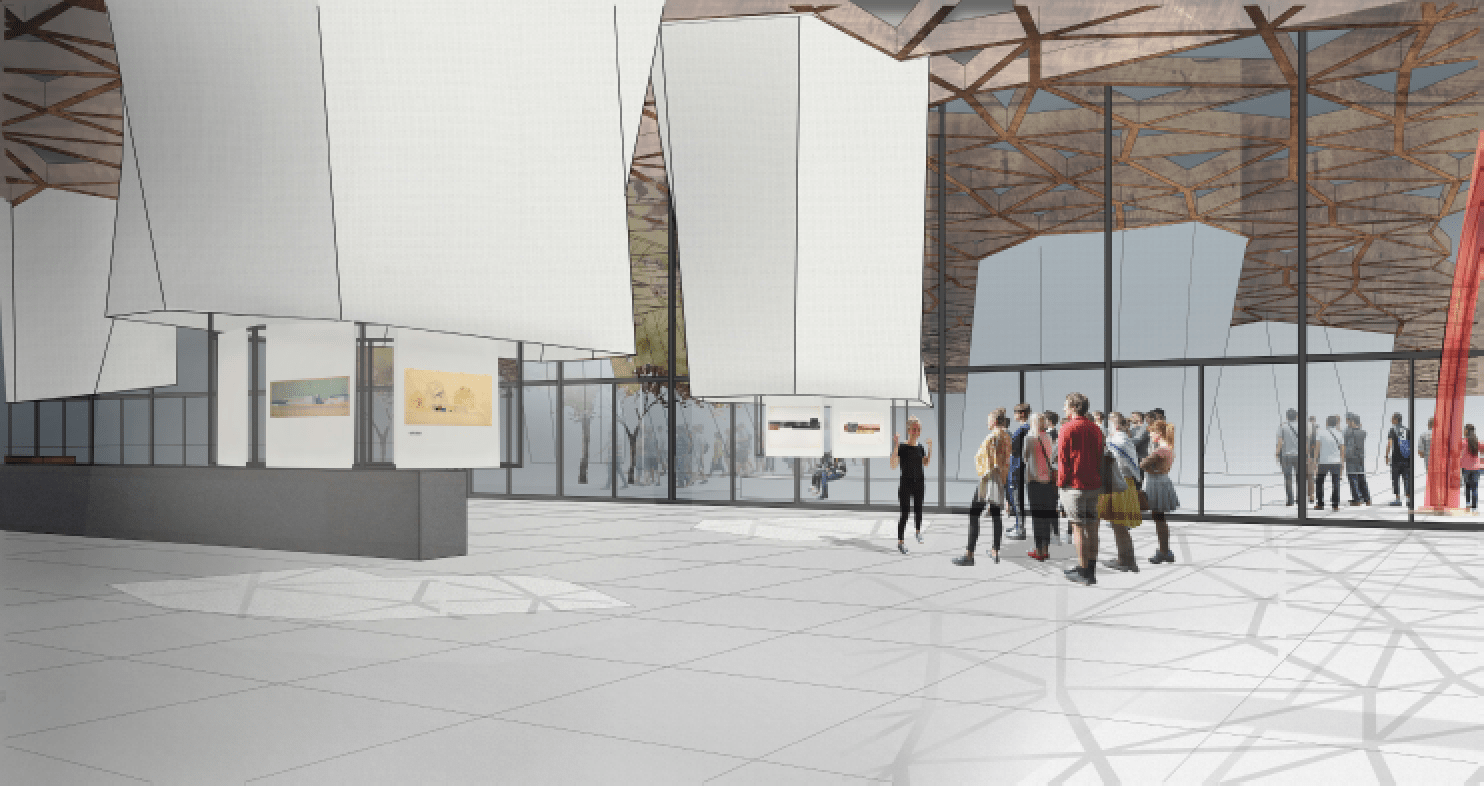

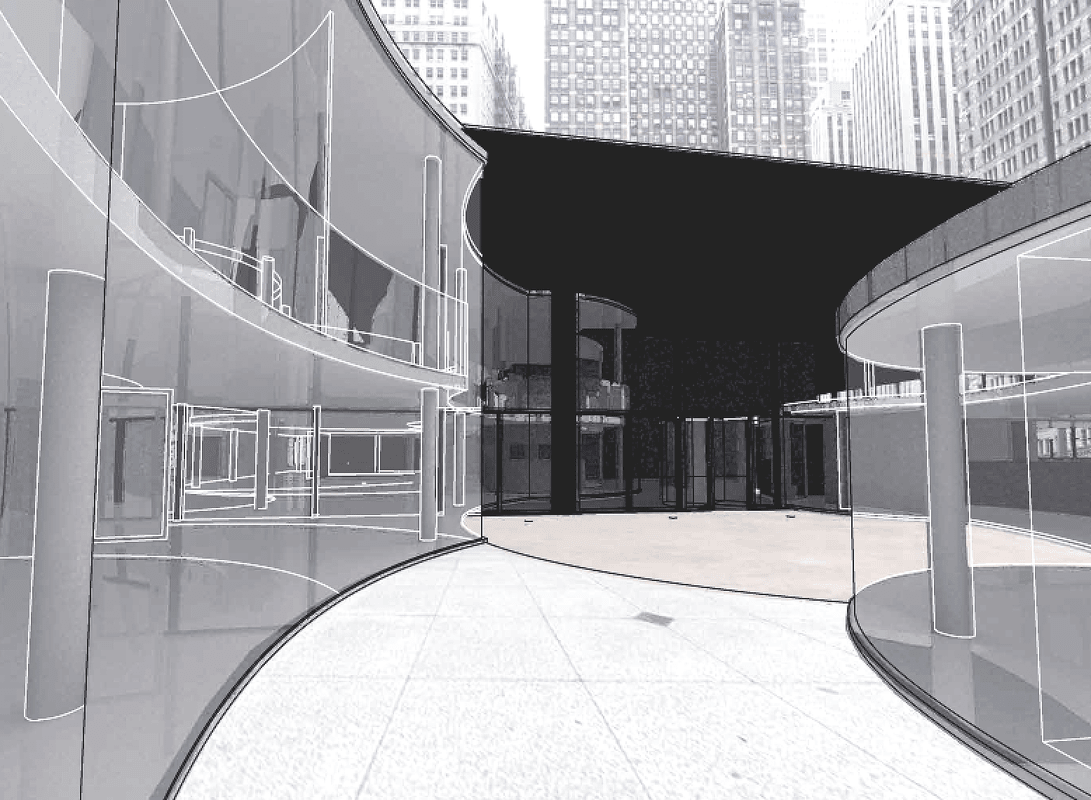

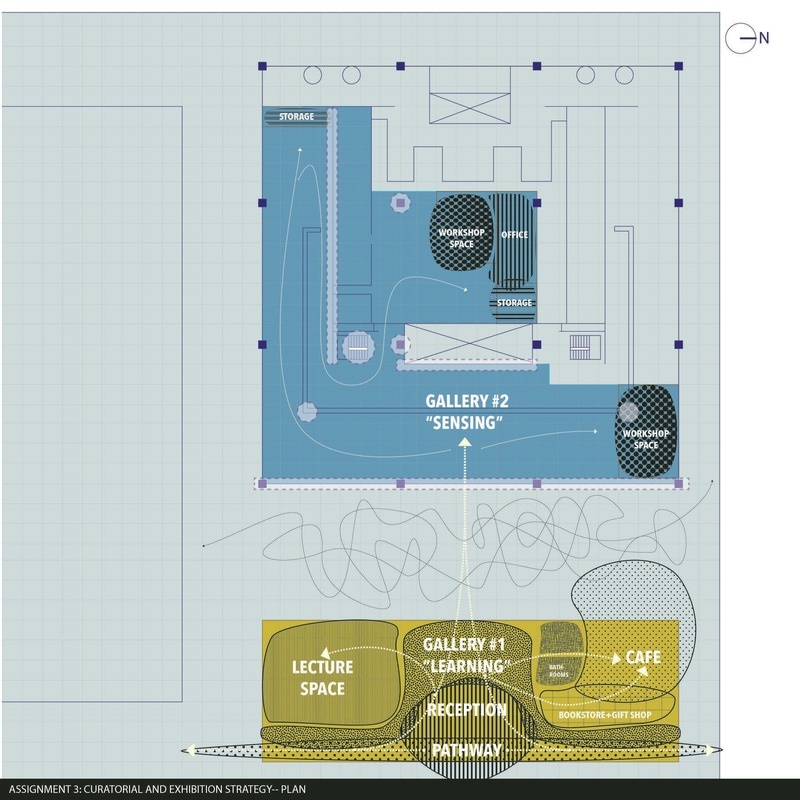

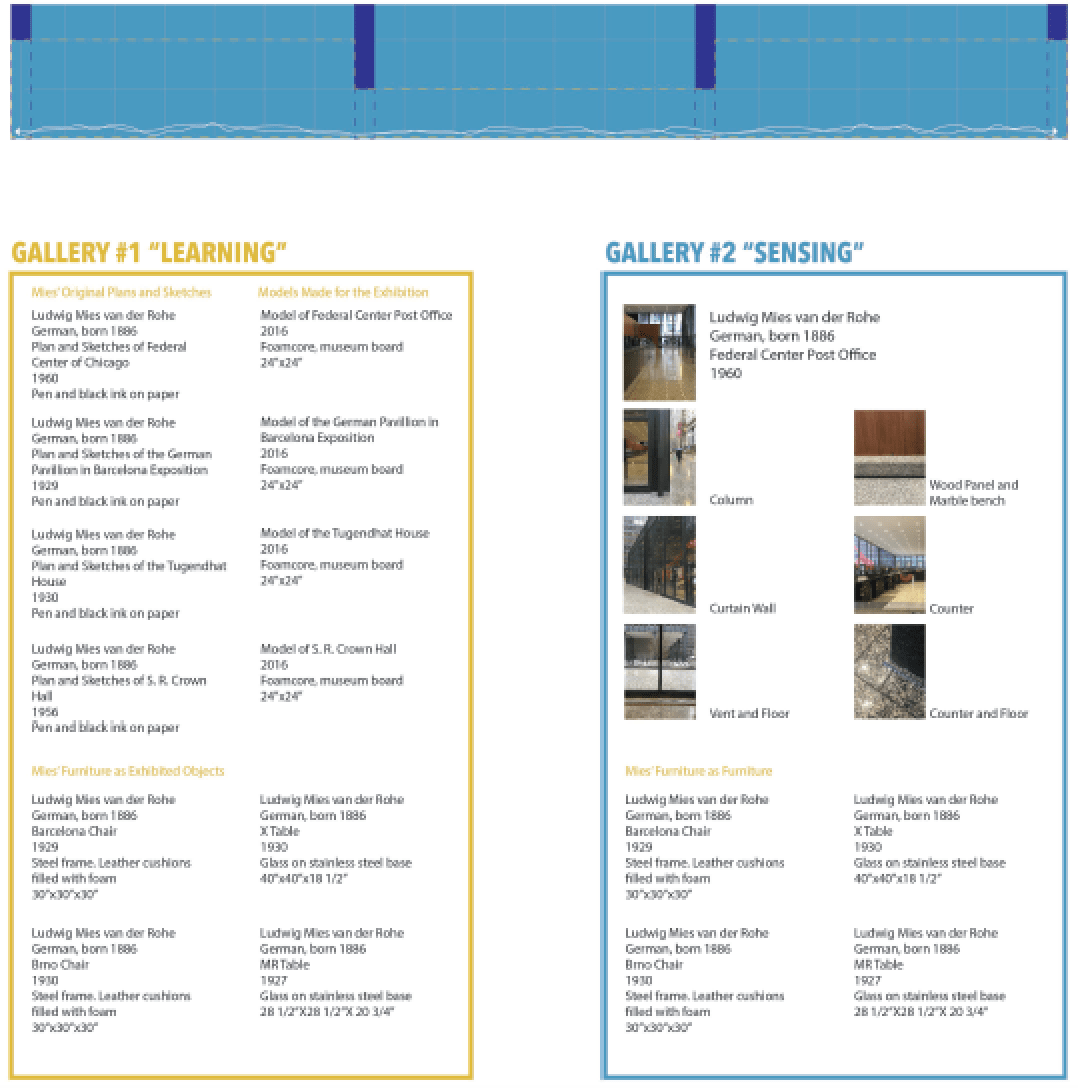

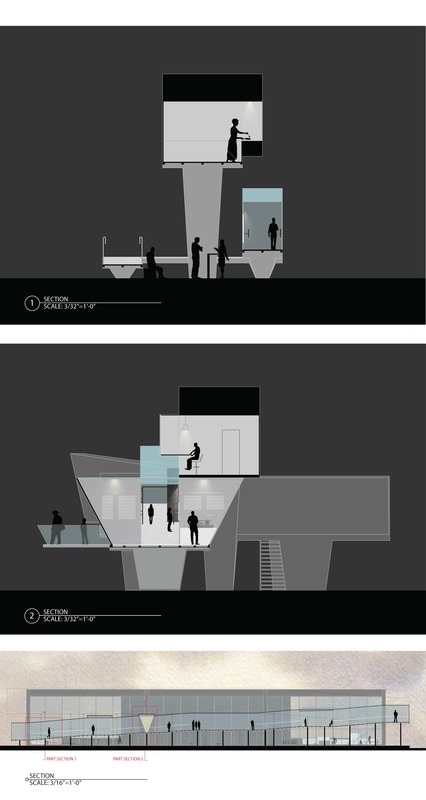

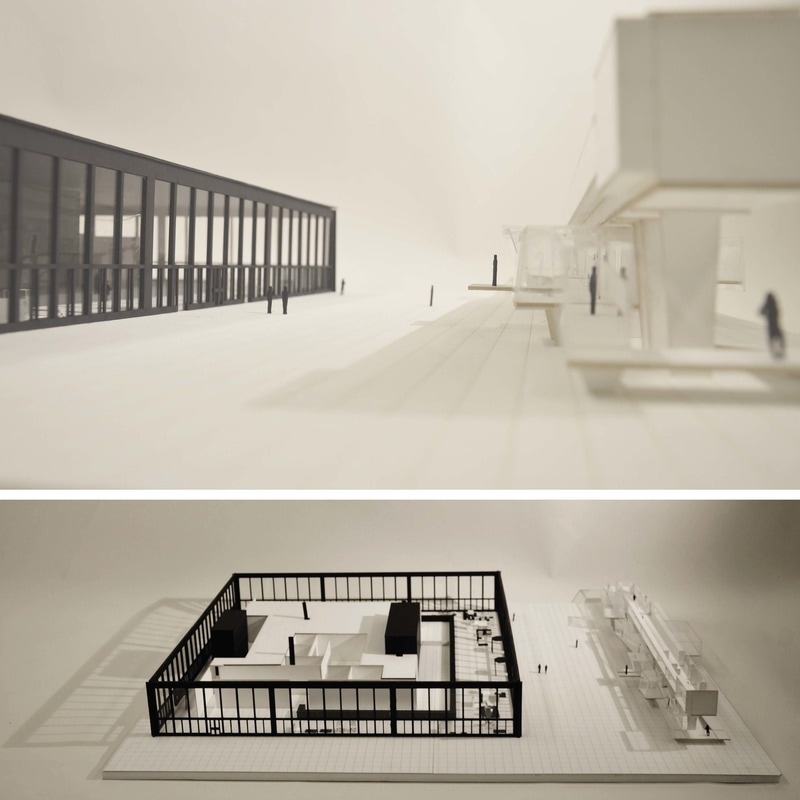

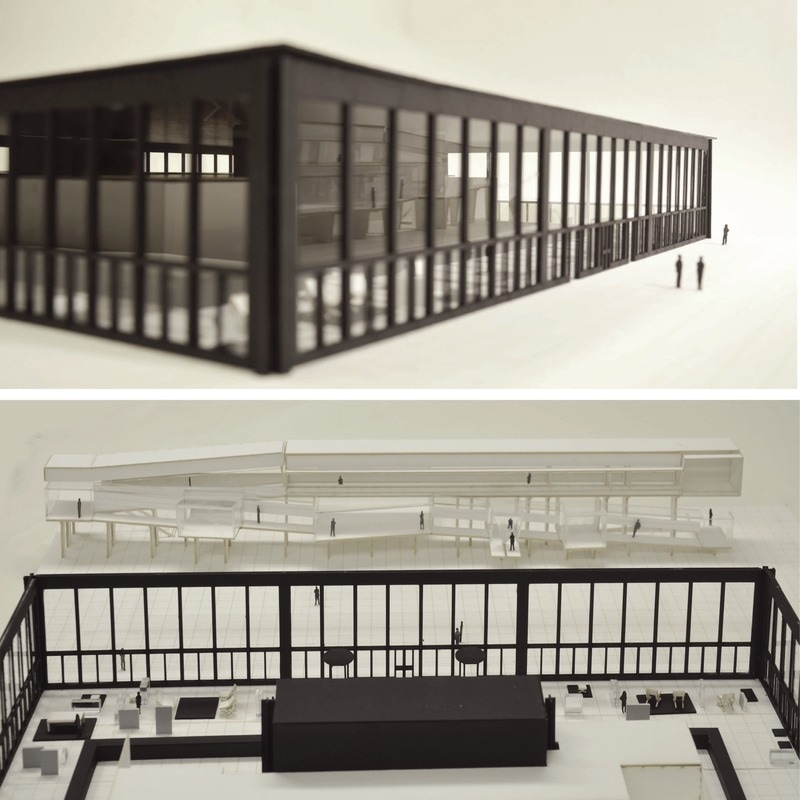

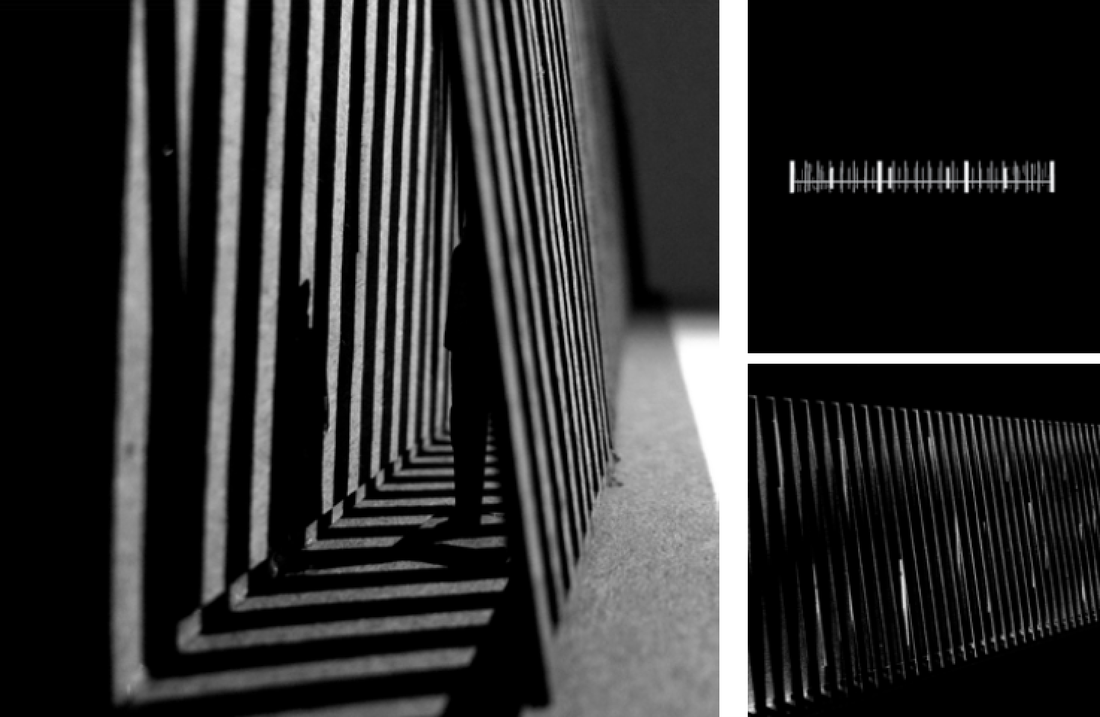

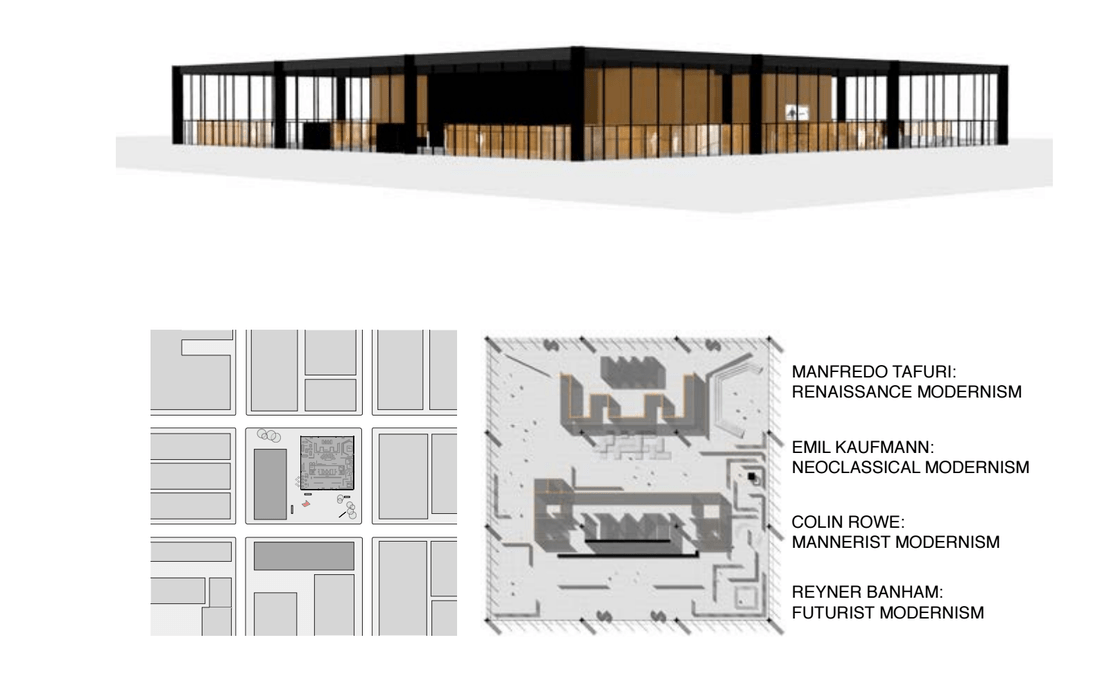

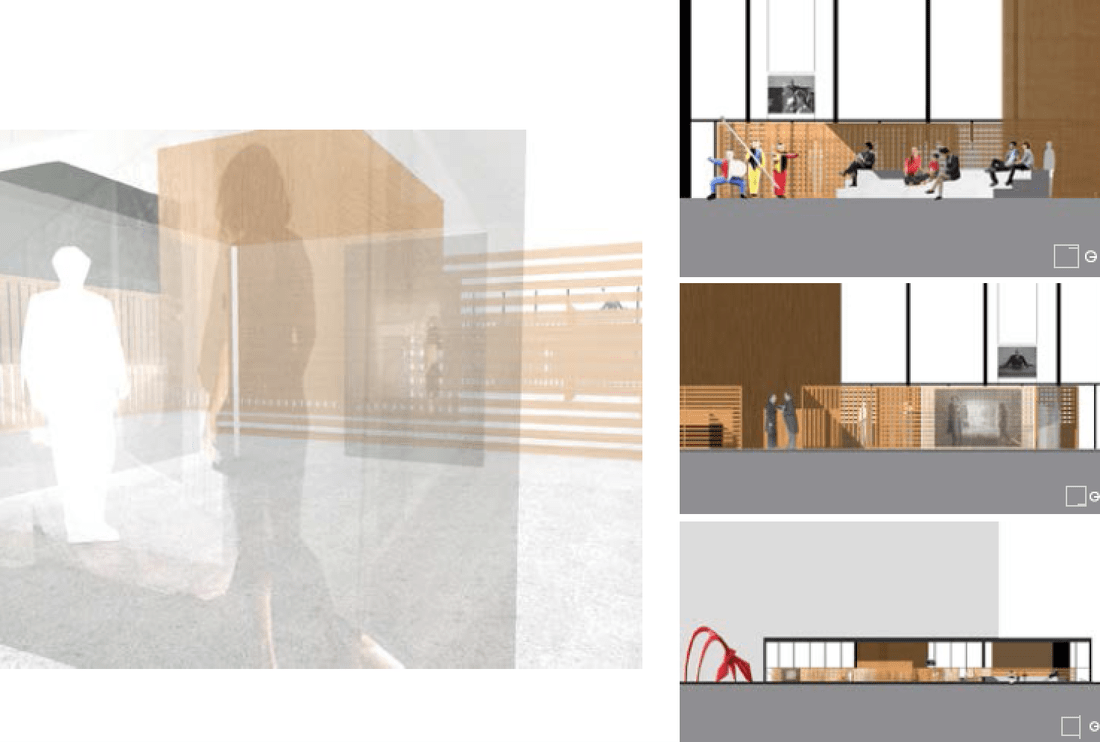

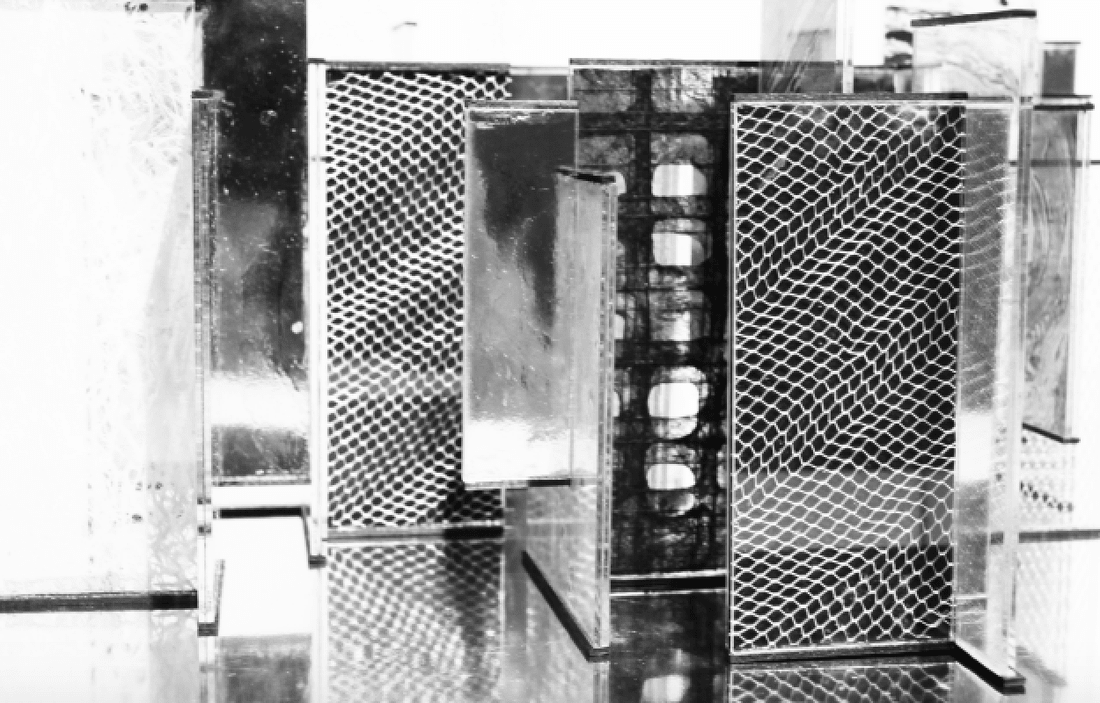

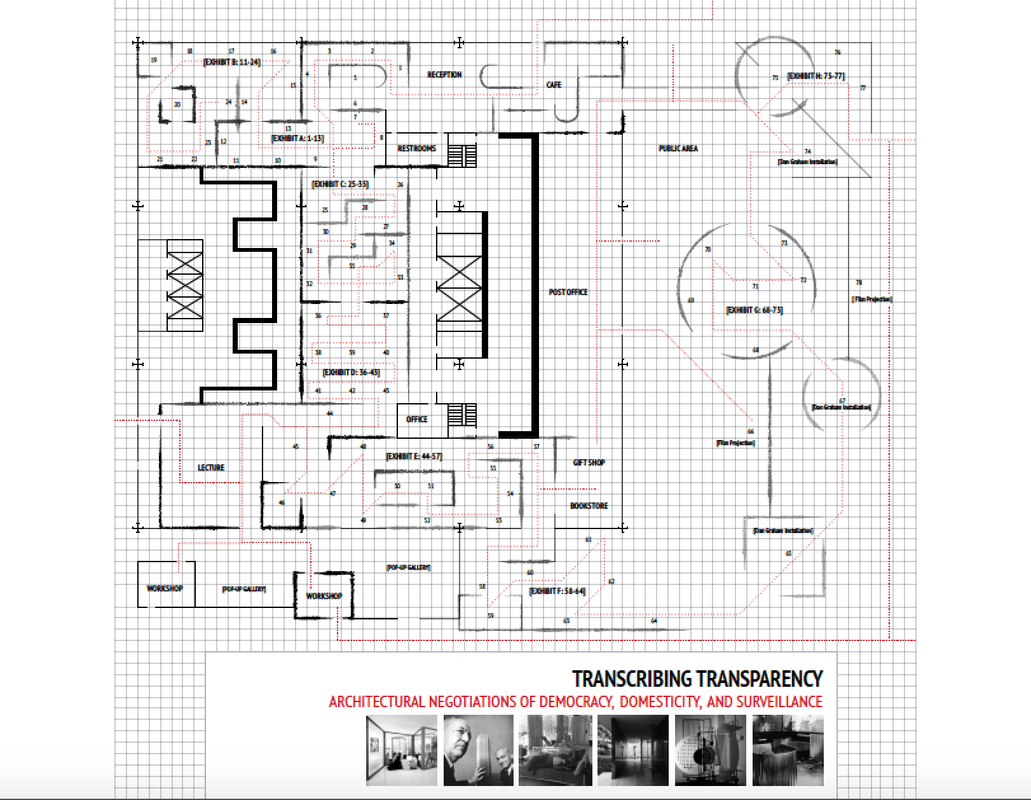

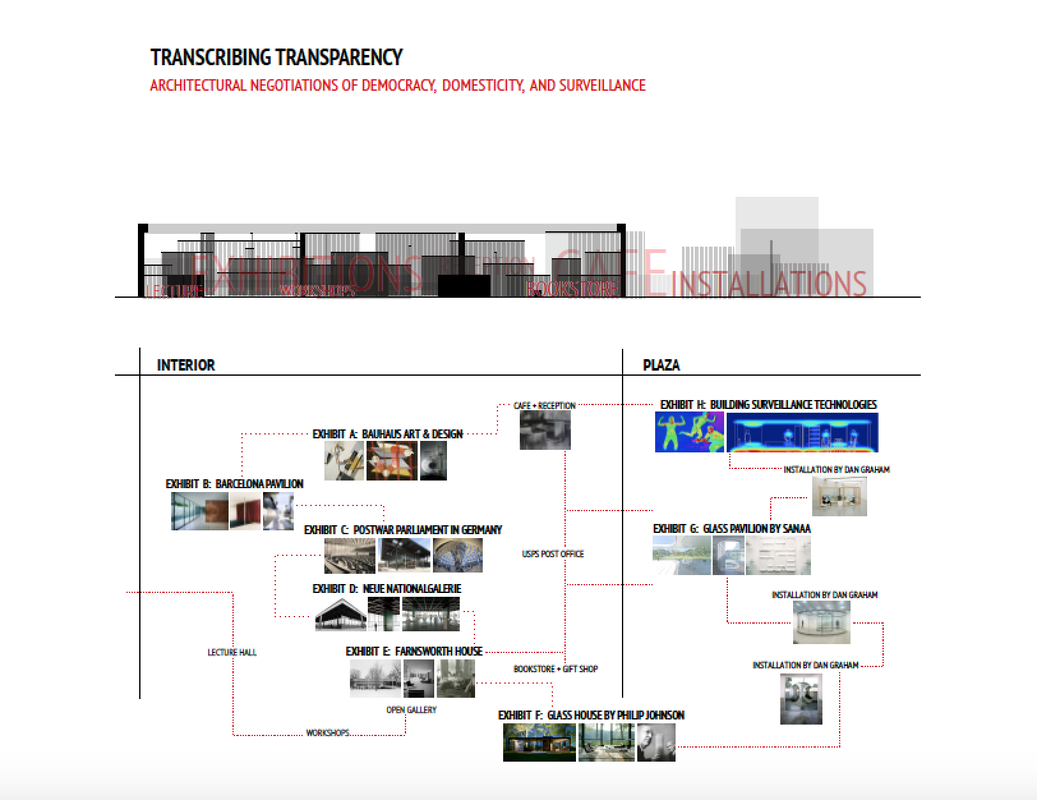

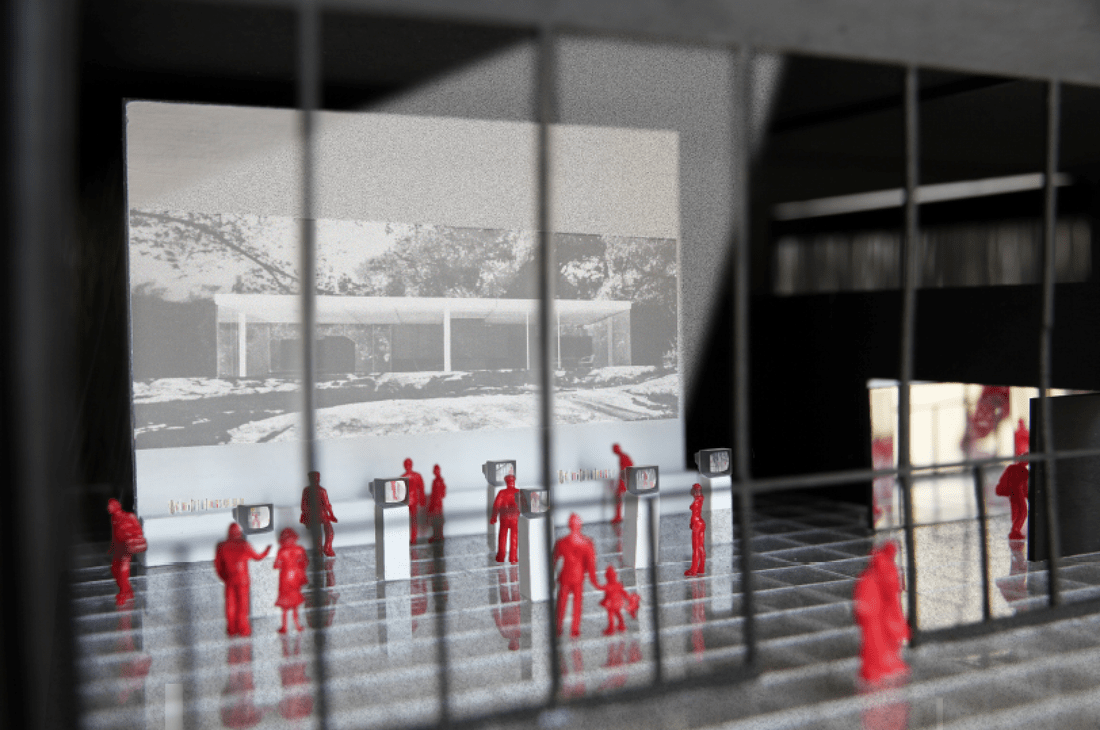

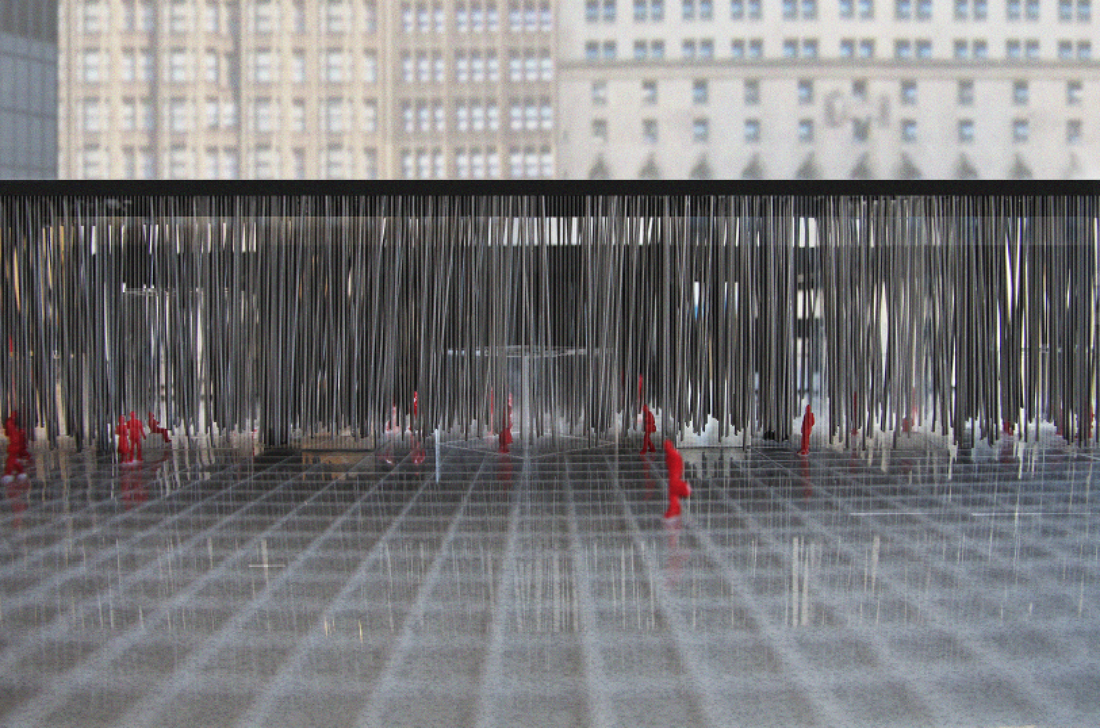

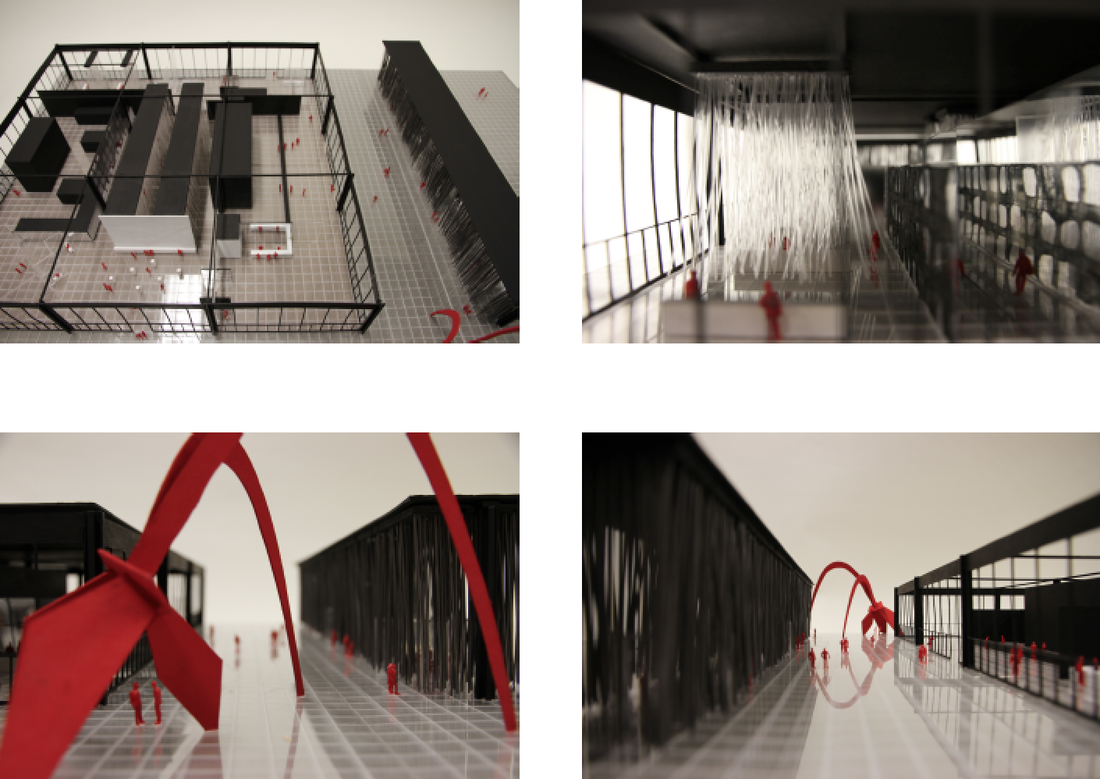

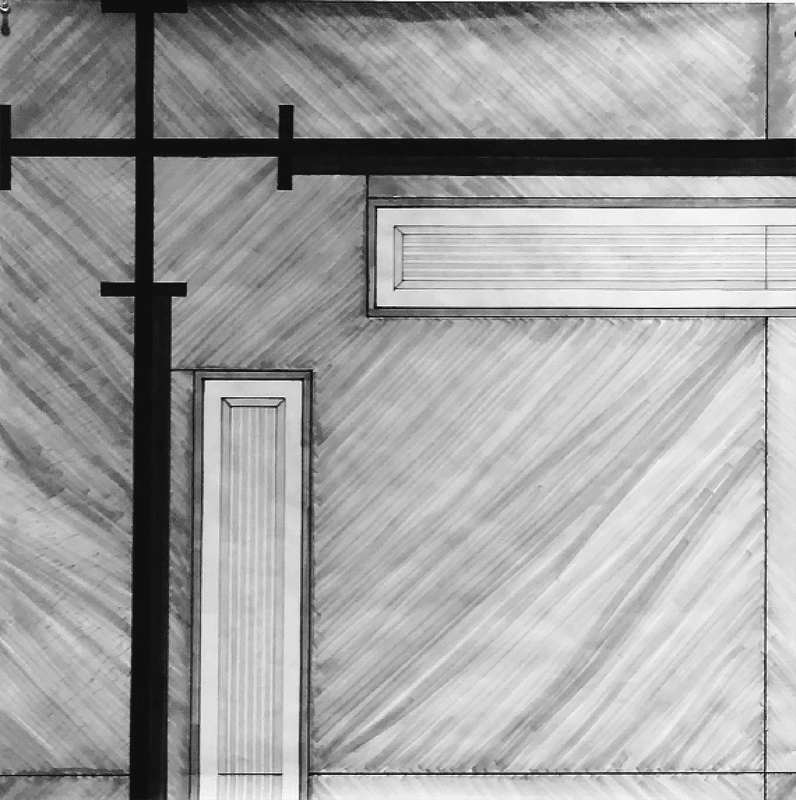

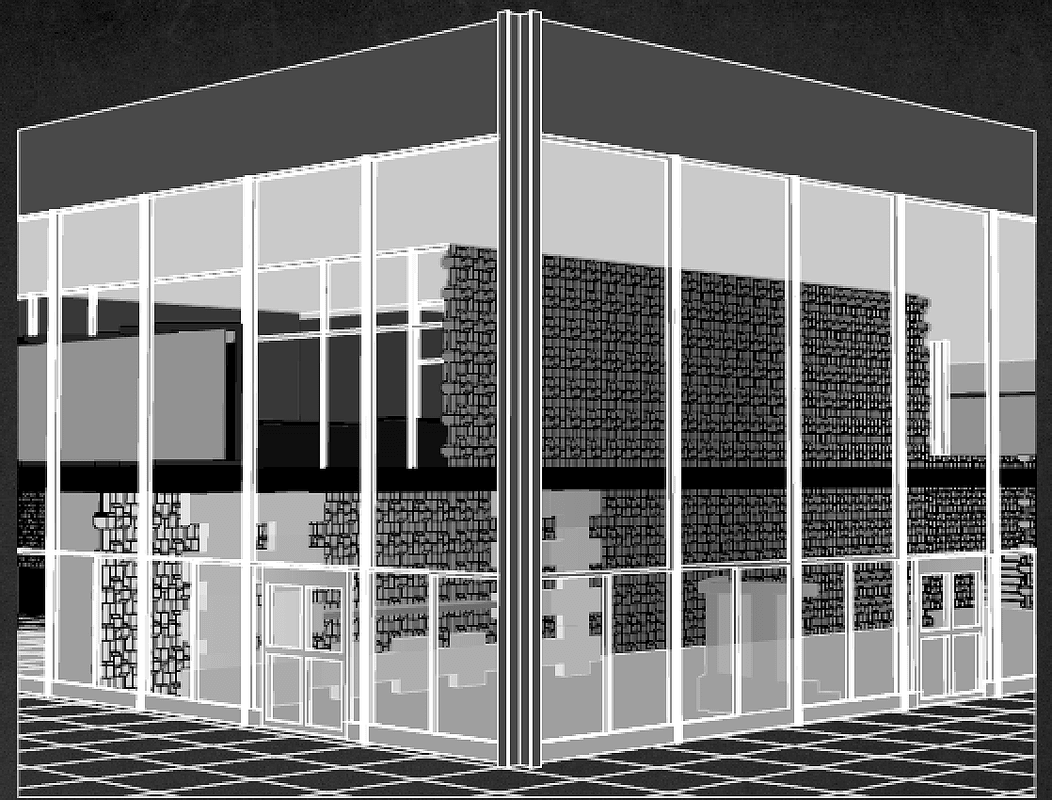

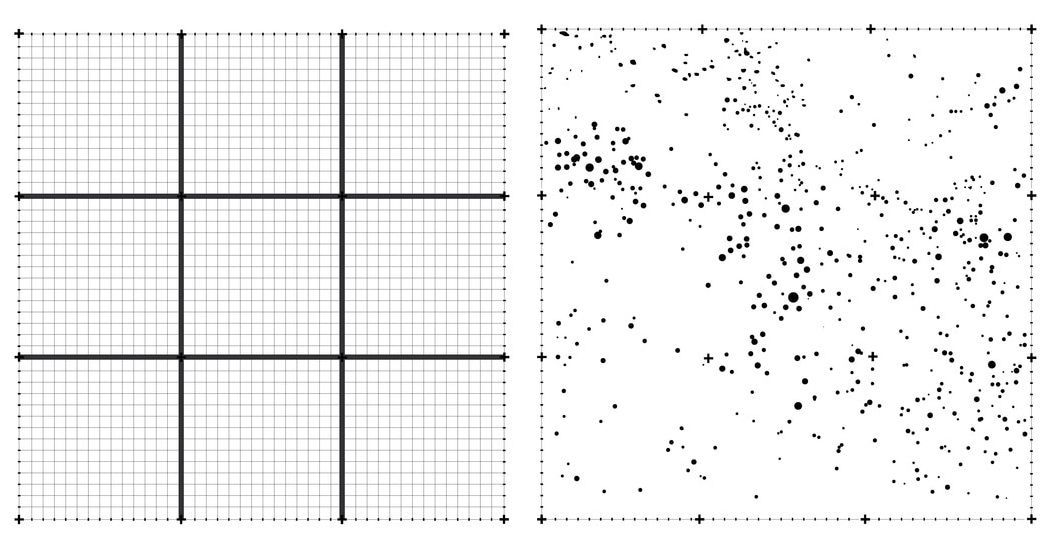

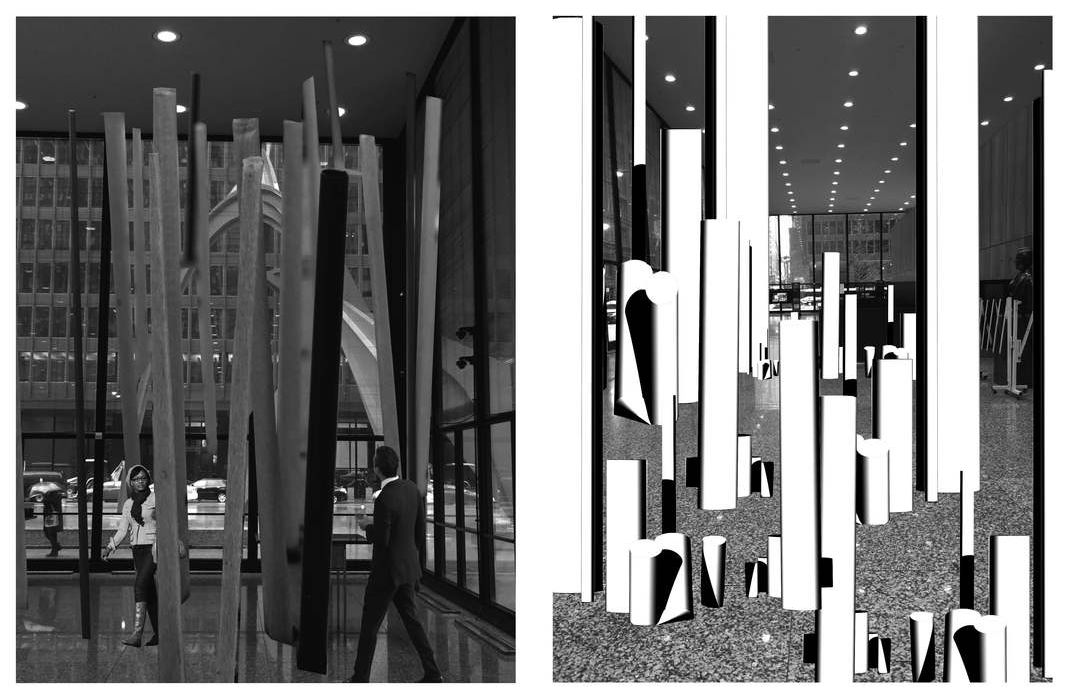

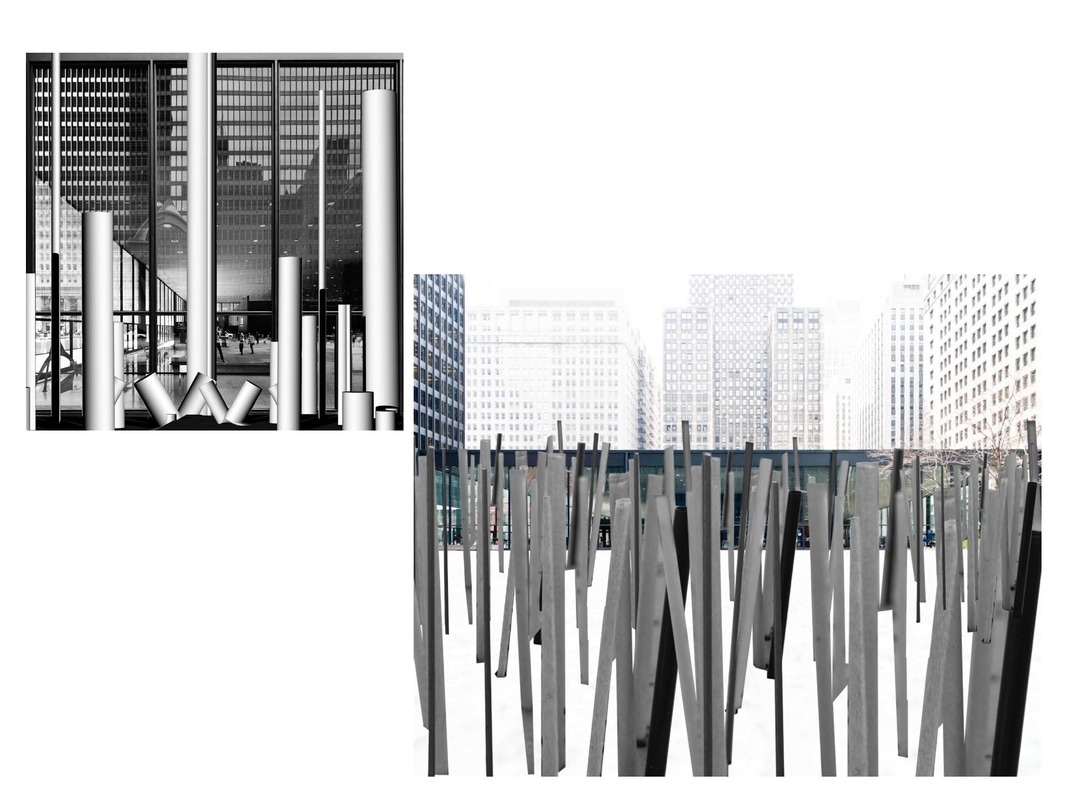

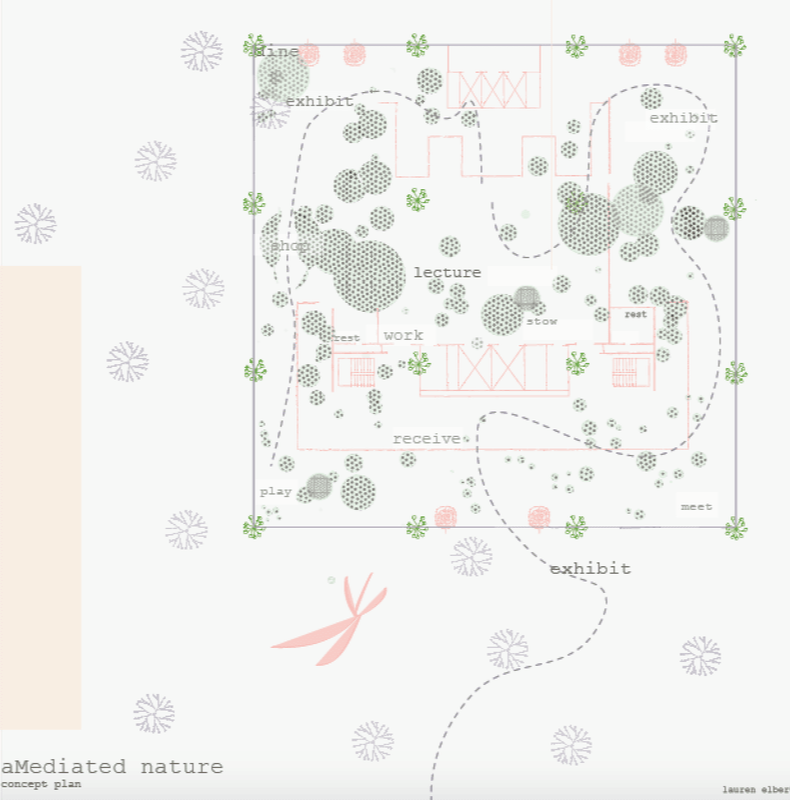

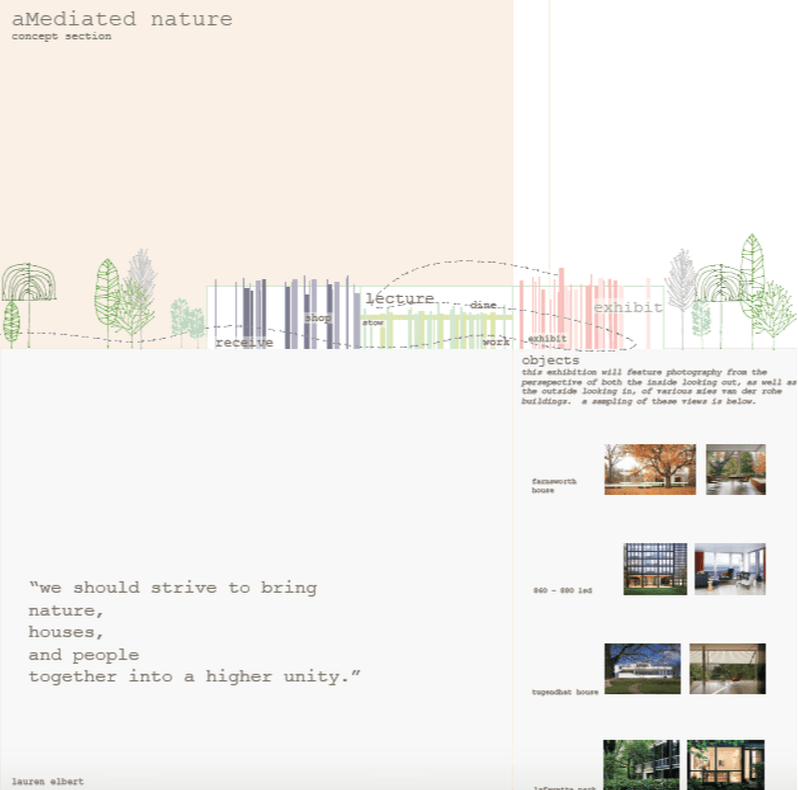

Mies’s Loop Post Office in Chicago provides an exemplary building for the study of skins in architecture. The building’s large steel beams painted matte black are separated from the non-load bearing exterior walls, which are full height glass and stretch along four sides of the building. The walls are only broken up only by the steel I-beam mullions. The glass façade reduces the perception of weight while accentuating the building’s transparency. Its materiality alludes to the thin, light and diaphanous qualities that one would associate with skins. The separation of the load-bearing structure and the non-load bearing enclosure has afforded enormous freedom for the exploration of architectural space in the 20th century. The building skin, on the other hand, becomes a surface opened to investigations through the various strategies of material, perception and programmatic thickenings. The opportunity for discovery is vast. Lina. Inside Mies's Mind. Tyler. Transportable Skins. Rebekah. The Ghost of Mies. Alex. Mies and Movements. Melis. Trangressing Mies. Suzie. Sensing and Learning Mies. Jordanna. The Four Modernisms. Olive. Transcribing Transparency. Molly. Capturing Corners. Dana. Mies and the Weathering in Time. Lauren. aMediated Nature.

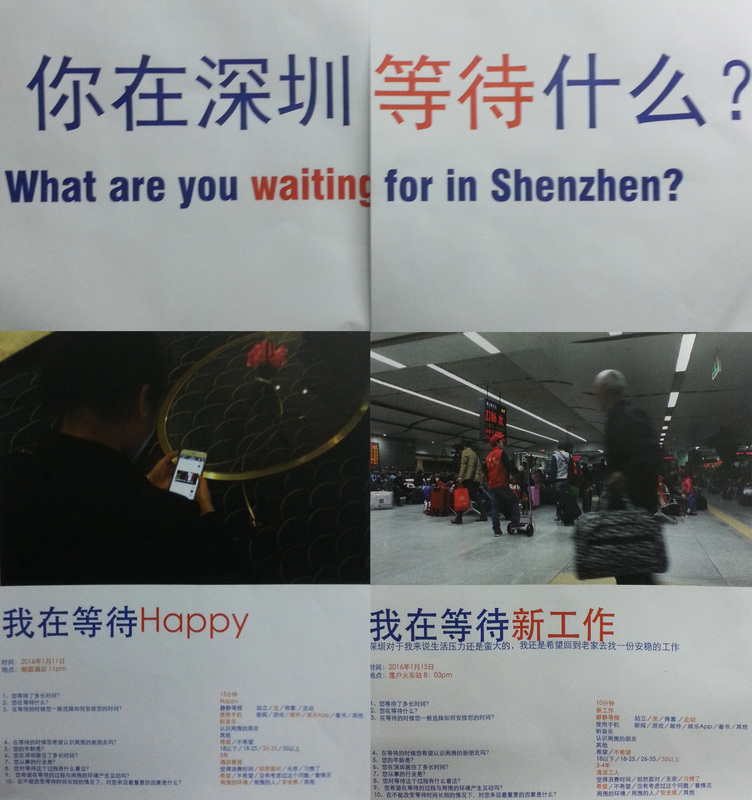

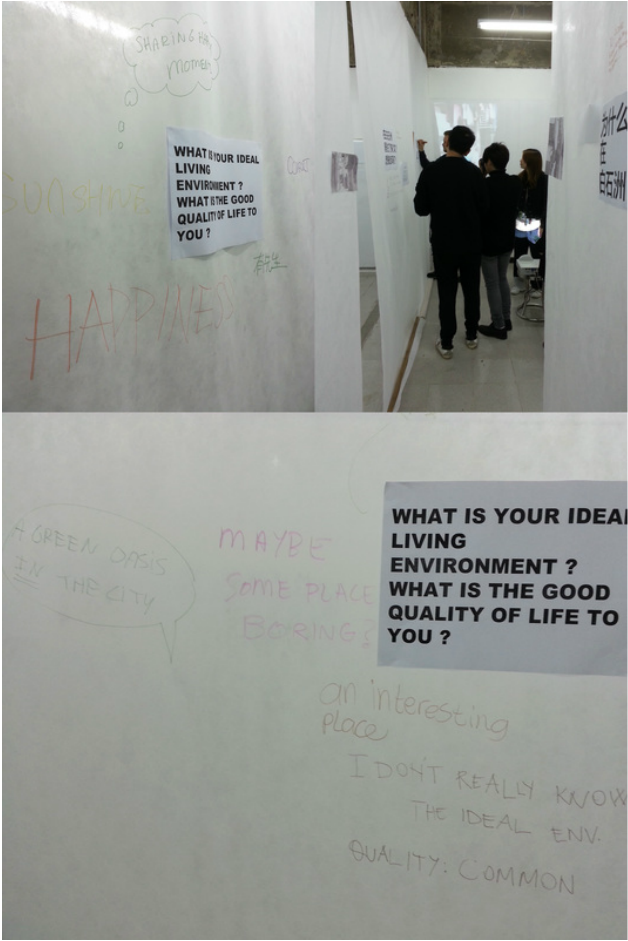

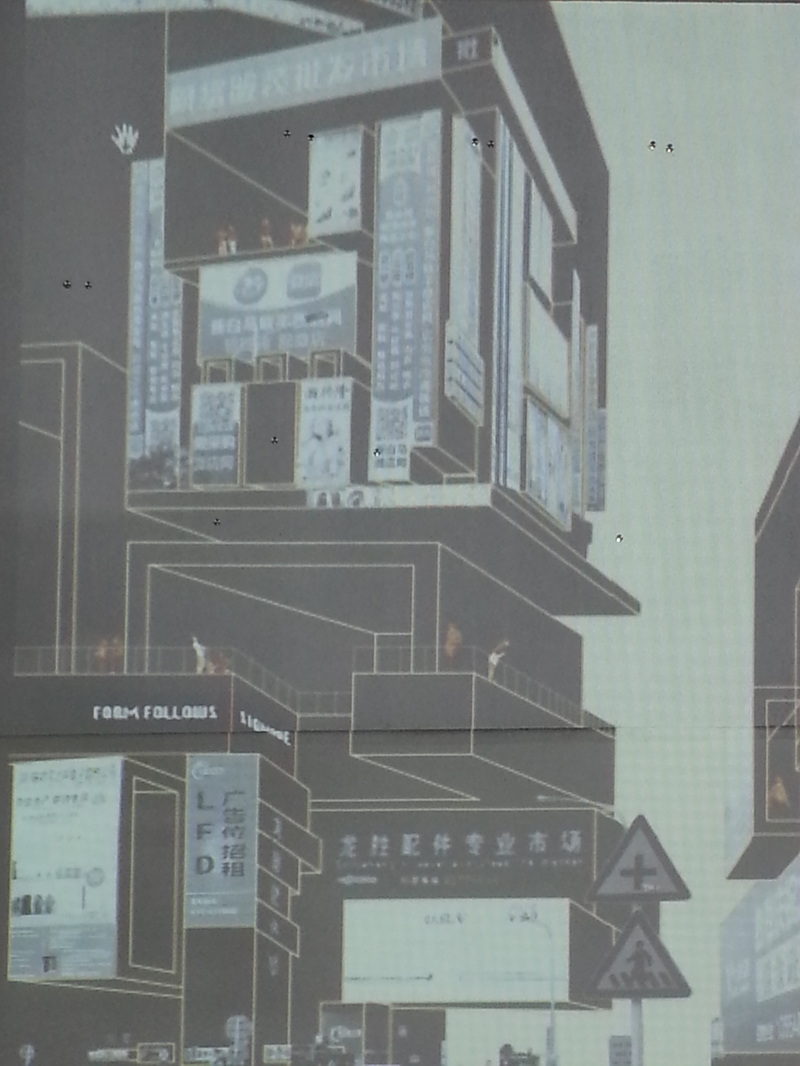

Learning from Shenzhen: The City as a Studio, was conceived and led by Thomas Kong. It formed part of a series of studios organized by the Aformal Academy during the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture. In this 5-day studio, participants were involved in a number of micro, on-site investigations centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in China’s first Special Economic Zone. Waiting Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work. Uniform The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority. Good life Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond. Form follows signage Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage. Shenzhen Vending Machine Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, the body and human relationship. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired. Drawing Memories

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life. Architecture possesses a surplus.

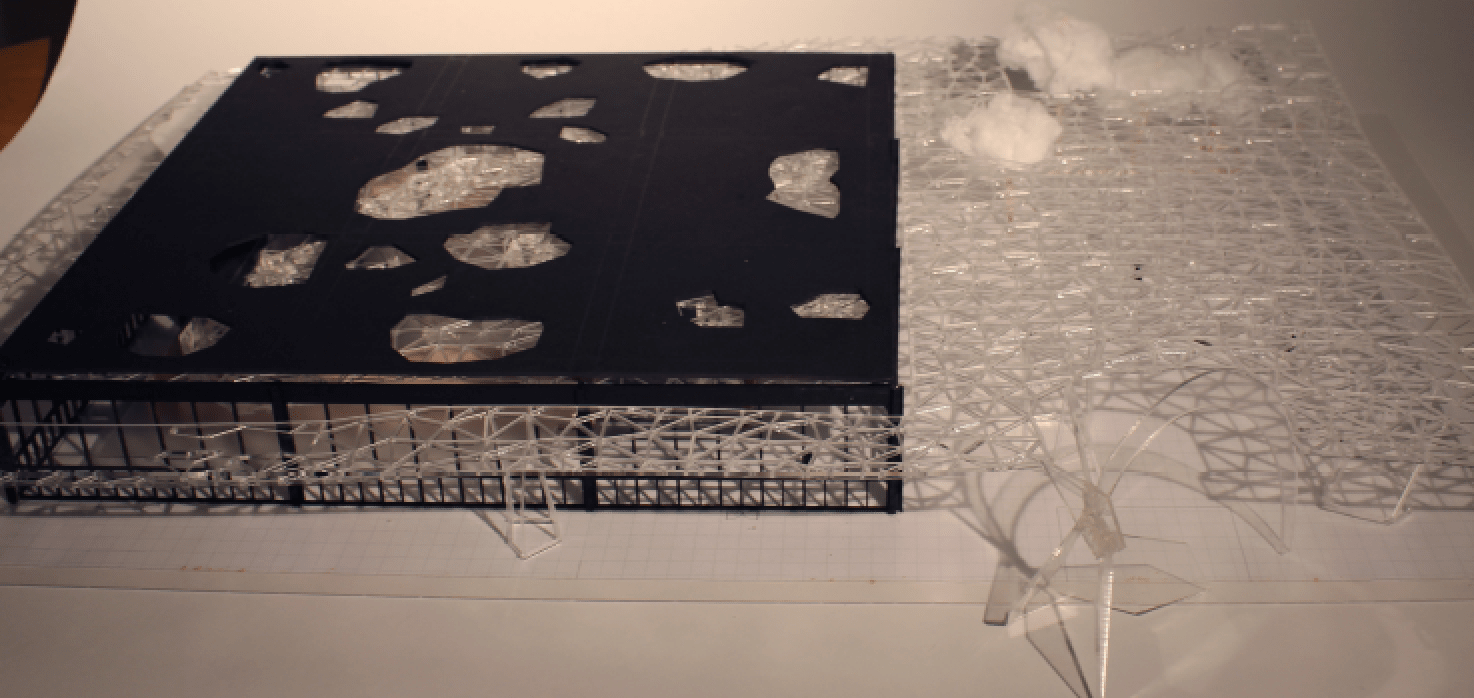

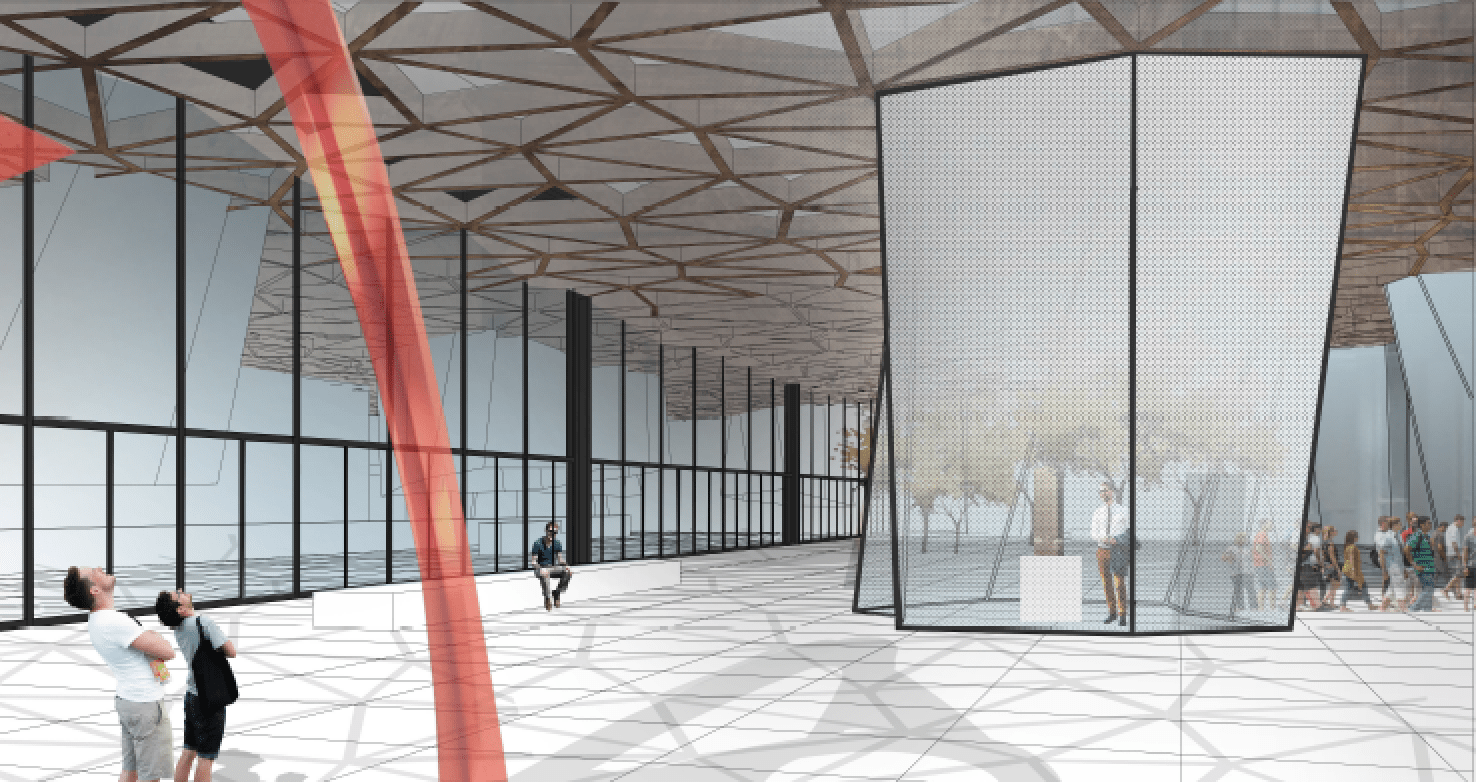

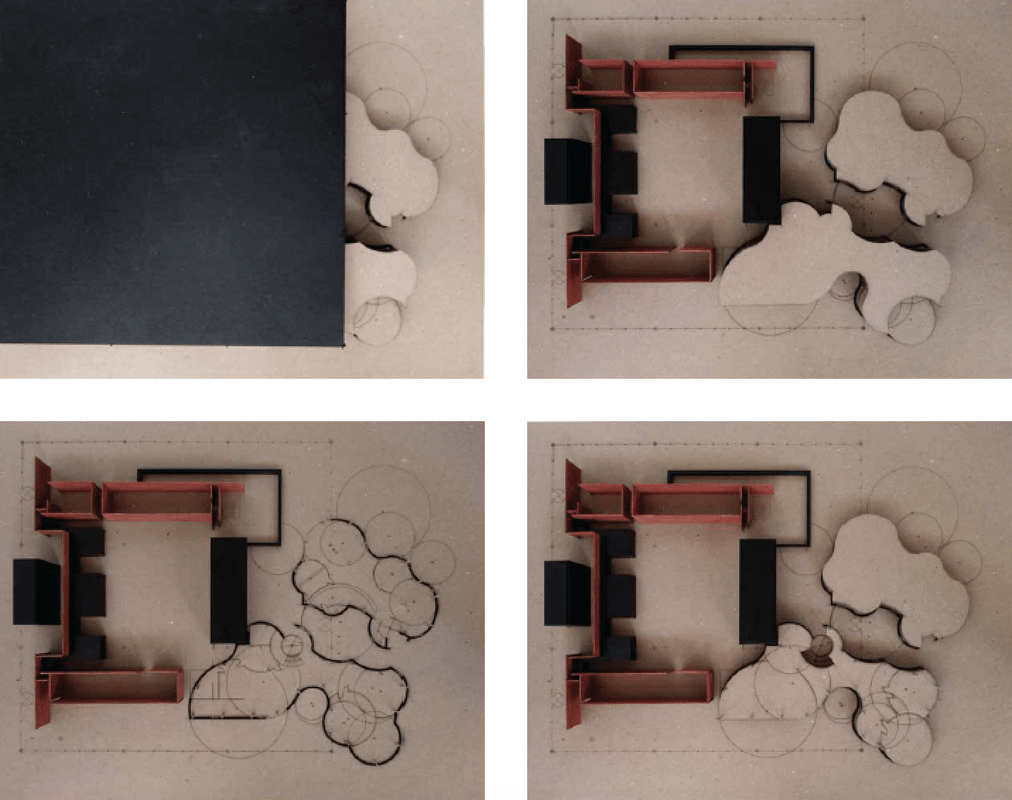

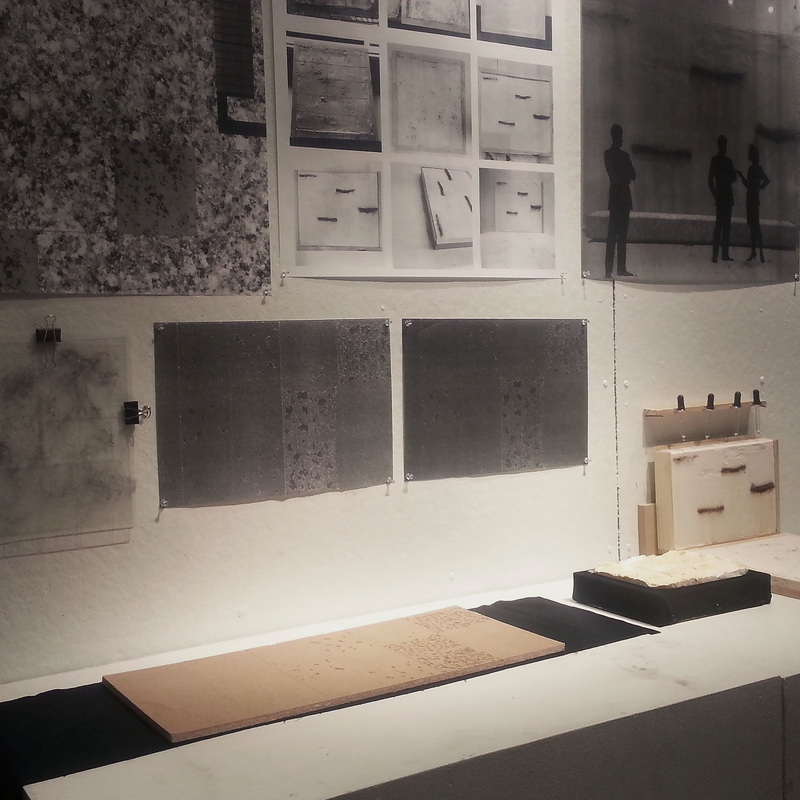

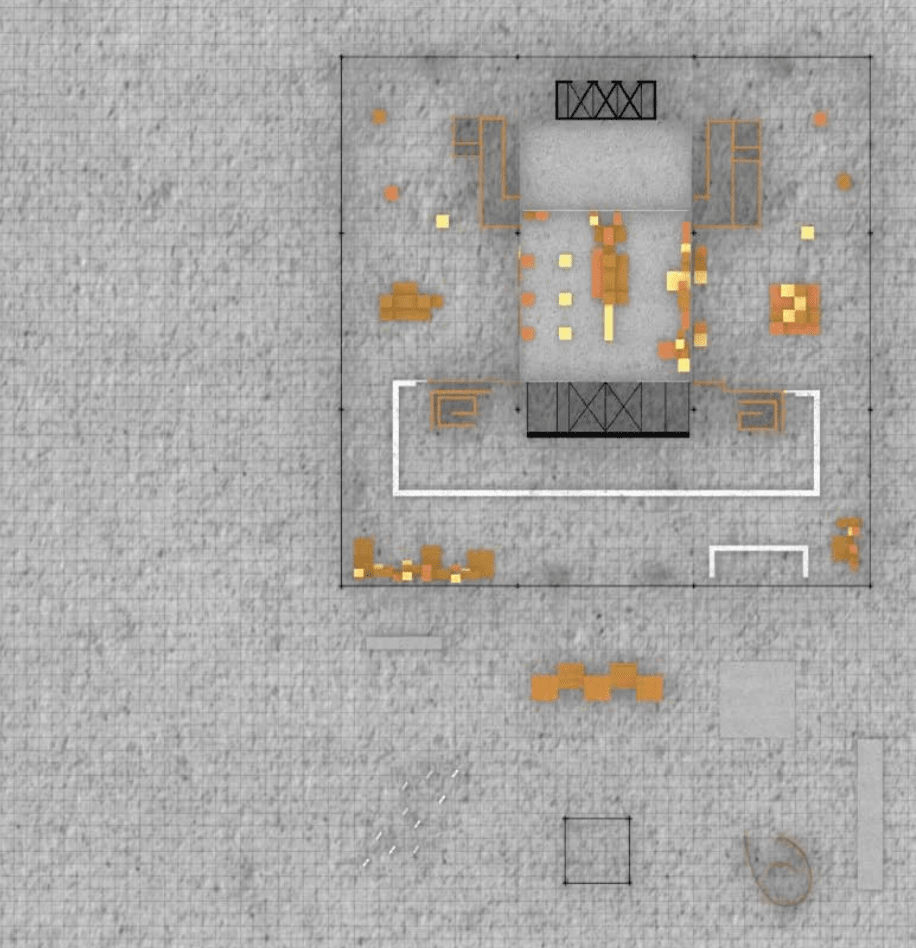

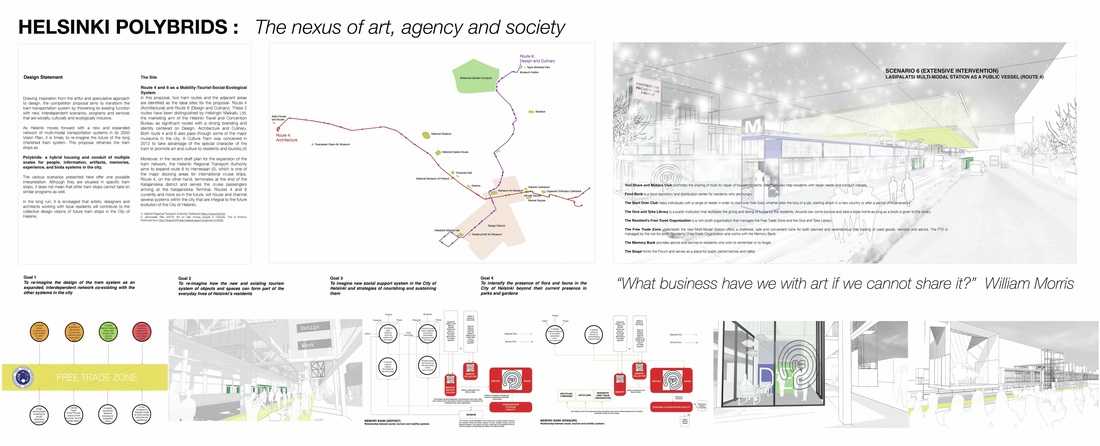

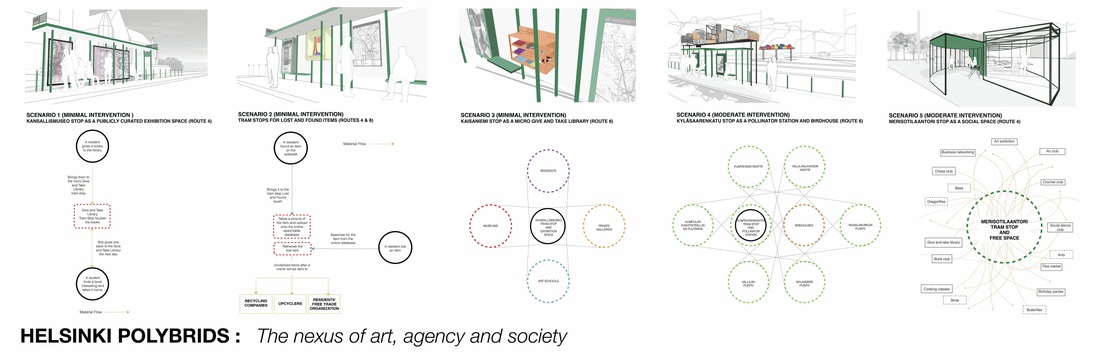

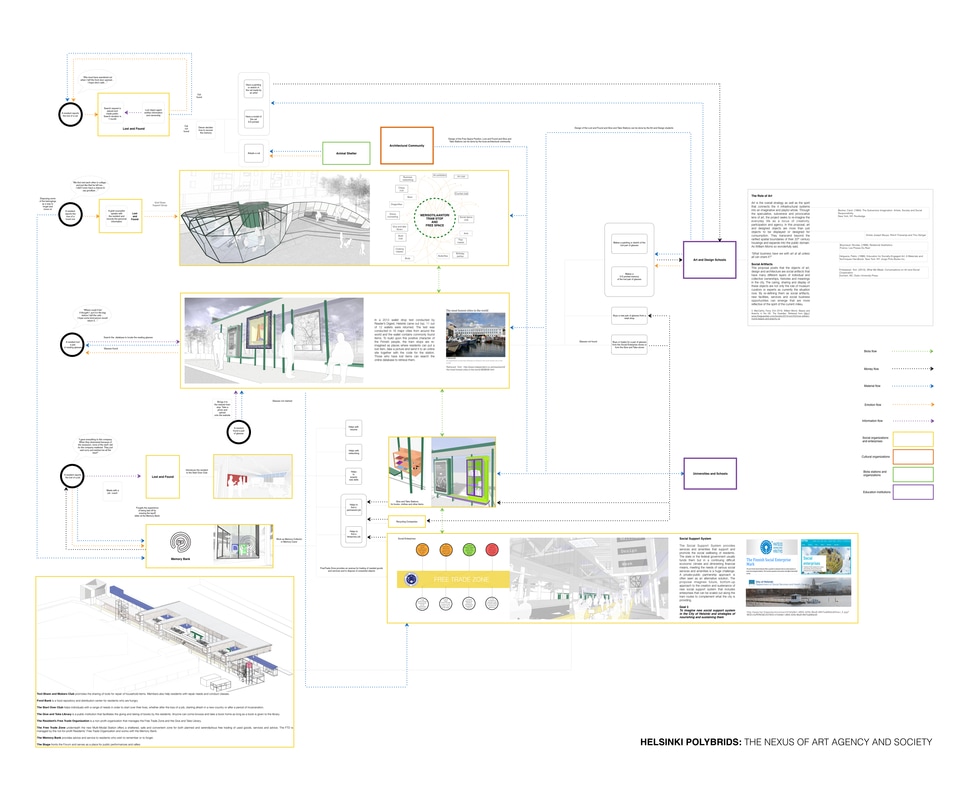

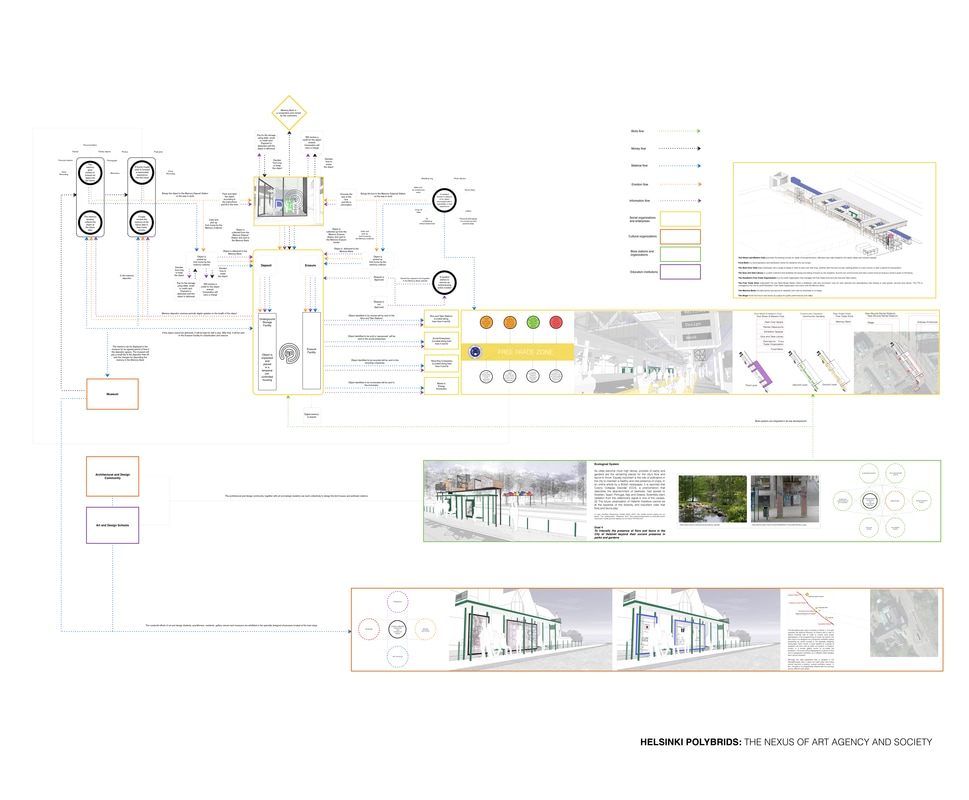

It possesses a generosity beyond designing a building or the artifact itself. This surplus is what gives meaning to a building and permits architecture to exist in other forms and media. It reminds me of a statement that one can ‘do’ architecture without designing a building. Or when the late Raimund Abraham said that to be an architect, all he needed was a pencil and a piece of paper. Whichever journey one takes, the quest for architecture has to begin with the architect and no one else. In fact it begins with the education of an architect. It begins with a search- by questioning fundamental aspects of the human condition both historically and contemporaneously because architecture is material form and space that articulates the human condition in all its failings and goodness. Recall the Nazi’s use of architecture in the expression of its warped, destructive and horrid ideology. On the other hand, see how Gaudi strived to embody the highest spiritual aspirations in humanity through his yet to be fully completed Sagrada Familia or John Hejduk’s poignant depictions of loss, remembrance, desire and love in his powerful drawings of angels and their housings. The search has to manifest into an act (not necessarily in designing a building) and must be carried out with sensitivity and empathy because architecture must be an affirmation of what is ethical and all that is good about humanity. Sometimes the action demands the architect to resist or subvert. In other moments, to strengthen, protect and shelter. The architect constructs a world. By this, I mean the architect structures and orders spheres of human experience through the thoughtful and intelligent use of media. The process is as much influenced by the character and propensity of the media as the inner voice of the architect. It is a voice that is first recognized and nurtured while in architectural school and matures through the life of the architect. It is shaped by cultural specificities, personal experiences and reflections, which re-emerges from the architect in in myriad forms and ways. Donald Schön notion of the reflective practitioner echoes this act of design that is informed by a continuous feedback loop of reflection, understanding and action. Each stage of the process moves from confronting something new in the beginning, drawing from one’s past experience in probing, testing and transforming the initial condition while creating a new understanding for the architect. It is a process of educating oneself. In other words, the life of an architect’s education is inexplicably linked to the architect’s process of understanding and awareness of his or her place in the world, which does not stop after graduation but continues into the professional world. It is a lifelong process of questioning and searching that marks the arc of an architect’s growth and development. "Helsinki Polybrids: Nexus of Art, Agency and Society" has been recognized by the jury panel of the Next Helsinki international architectural competition chaired by Michael Sorkin. Among the jury members are Juhani Pallasmaa, Walter Hood, Sharon Zukin and Mabel Wilson. There were over 200 entries from 40 countries. ”Almost like a dictionary of human thought and collective imagination.” (Free quote from jury member Juhani Pallasmaa) https://www.facebook.com/TheNextHelsinki 'Almost everything in the world today is mobile. Why should art be static?' Juhani Pallasmaa #NextHelsinki https://twitter.com/CheckpointHki https://homes.yahoo.com/news/adventures-architecture-next-helsinki-adds-212325775.html http://www.nexthelsinki.org/ My shortlisted proposal and the other 200 over entries form a collective and creative counterpoint to the corporate driven art market initiative of the Guggenheim Museum. Our proposals are part of the major debate over the long term value of the Guggenheim Helsinki project, which has faced massive push backs from Finnish citizens and prompted the setting up of an alternative international architectural competition. Since the Great Recession, city officials are realizing that big, iconic projects are becoming harder to push through in parliament because citizens are demanding for greater investment in social infrastructures instead. However, to avoid financing public art is also ill-advised as it is an important contributor to the culture and economic vitality of cities. A new model of art-making, curatorial practice, presentation, support, housing and archival will need to be designed. To avoid succumbing to the seduction of another one-off piece of iconic architecture costing billions of dollars to build, exploits cheap migrant labor and requires long-term, expensive maintenance, my entry re-frames the making, curating, exhibition and sustenance of artworks as a bottom-up, community driven activity that involves a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the city. It sees economic value of art not limited to how much one can afford to pay and sell at an astronomical price later but a more socially distributive model where the ecology of production, distribution and use (and re-use) is intertwined with the everyday life of the Finnish residents. Instead of scaling up even bigger as most contemporary museums seem to suffer from these days, my entry proposes to scale-out into the different neighborhoods by borrowing the city’s existing tram lines and stops. Through the process of creating the multiple art polybrids in the city, the tram lines and stops, which serve a vast section of the Helsinki residents and are in a state of decline, get to be refurbished and renewed at the same time. This twinning of art and public infrastructure makes good economic sense. The art polybrids are also way more accessible than a singular building, and are more effective in harnessing the collective imagination and creativity of the people. Museum goers are no loner passive consumers of a paid experience. They have the power and the opportunity to co-curate, to make art and in the long run, strengthened community bonding and identity, as well as fostering a more inclusive and socially resilient society. Helsinki Polybrids: The Nexus of Art, Society and Agency is therefore designed to offer a multi-scalar, horizontally distributed, economically and socially sustainable re-framing of art, its production and experience for a 21st Nordic city. The entry was exhibited in the recently concluded Tallinn Architecture Biennale in Estonia under the Research and Development Lab, which saw 1600 visitors over 12 days. The result of the Next Helsinki Competition has also been featured in many influential architecture and design websites, and the Finnish Broadcasting Company. In 2016, the book UR: NextHelsinki by Terreform containing the short-listed entries and essays will be published to document the process and the discourse surrounding the alternative competition, which no doubt will rouse further interest and attention. Academics too, have shared their perspectives on the contentious issue. Writing on the shortlisted entries for the Next Helsinki architectural competition, Peggy Deemer (2015) wrote, “The cultural value of this competition will probably not be in the form of creative capital—although the shortlisted proposals offer excellent thinking on what makes a city work such that art can be appreciated.” (para. 9) Referring to the Next Helsinki architectural competition again, Deemer (2015) was convinced that, “its very existence as performance, display, and conversation—its cultural capital—forces the Guggenheim to scurry and scratch for its rewards.” (para. 9) Besides being in a critical moment in the global discourse to unpack, critique and contextualize the value and purpose of such lavish projects, my shortlisted entry offered an alternative model to the Guggenheim museum franchise that weaved together the art, mobility, tourism, social support and ecological systems in the city. On a professional level, my proposal is a continuation of my research on and formation of a parallel architectural practice and education model inspired by the arts. According to the Legal Information Institute (2015), the definition of the ‘the Arts’ by the United States Congress includes architecture, besides the commonly accepted artistic practices such as sculpture, painting and photography. This inclusive definition opens up the possibilities for the creative renewal of not only the architectural profession but the teaching and learning of architecture as well. The breadth and scope of design services have also increased enormously in recent decades to encompass service design, design activism and strategic design, to name a few of the new fields. The strategic design thinking and human-centered problem identification skills used by architects in their daily practice can therefore be developed and marketed as new skills-sets and services to buffer against another economic crisis. Fluid/Soundings in London and AMO in the Netherlands are excellent examples of such an interdisciplinary practice. On the other hand, the nomination of architecture collective Assemble in the U.K. for the 2105 Turner Prize in Art is a strong endorsement of design activism and the art-design nexus of contemporary spatial practice. In my conversation with a design strategist working in the multidisciplinary American architecture firm Gensler, it was very clear to her that their major clients are not only interested in just a well designed and sustainable building but also a strategic vision that aligns architecture with social and business innovations, as well as environmental stewardship. Architect Michael Sorkin, the organizer of The Next Helsinki architectural competition puts it most provocatively when he declared in an interview with the U.S. based Metropolis magazine, “We invite competition entries from any and all, includes any of the 1,700 losers from the Guggenheim competition whose work looks beyond simply building a museum on the site.” (M, Sorkin, personal communication. Jan 22, 2015). Reference Deemer, Peggy. (2015).The Guggenheim Helsinki Competition: What is the Value Proposition? Avery Review: Critical Essays on Architecture. Issue No. 9. Retrieved from http://www.averyreview.com/issues/8/the-guggenheim-helsinki-competition Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from Cornell University Law School site https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/952 Revised drawings showing the ecology of existing infrastructure, education and cultural institutions, social agencies and parks as spaces for art making, sharing, presentation and community engagement. Architect, Professor and competition judge Juhani Pallasmaa's acknowledging the Helsinki Polybrids entry in his essay, Back To The Starting Line.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed