|

During the first day of the facilitation session in To Kwa Wan, I introduced the Circle of Gift Giving to the group. Sitting in a circle, each participant gave a small present to the person seating next to him or her. The ritual required the gift giver to share the source and meaning of the gift to the receiver. As the circle of gift giving enfolded, we shared funny, down to earth and poignant stories behind each gift. One participant forgot to bring a gift and she bought one in To Kwa Wan. Being practical minded, she bought a bottle of WD 40 from a car repair workshop as a gift and hoped it would be useful for the gift receiver. Another female participant gave a movie ticket to the participant next to her. She explained that it was from a movie date but her partner failed to turn up. She ended up leaving the movie theatre holding the unused ticket. A participant gave a small coin, which came from a memorable trip to Taiwan she made with her father, while another gave an old high school exercise book. She shared that the book brought back memories of her school days in Hong Kong after being away for many years.

The participants had to learn from the sociocultural and economic life of To Kwa Wan residents, and come up with interesting ideas to archive the fast disappearing neighborhood over a one-month period. They came from all walks of life and were strangers to each other. Before diving deep into the task, I felt it was important to first form a community of learners through the ritual of gift giving. As Lewis Hyde in The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World so eloquently wrote, "...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears.” I was invited by the Make a Difference School in Hong Kong to be a guest facilitator for their 1- month in-situ studio in To Kwa Wan. Over 3 days in August, I gave a public lecture on the concept of Social Archiving and conducted discussions with the participants and local residents on the future of the neighborhood that was slated for re-development. Looking at To Kwa Wan superficially, one sees only the large number of car repair workshops, and would not have imagined a rich and diverse collection of social relations and history. Through my street conversations with the locals, I discovered a resident who played the flute to entertain passerby and gave a very good impression of singing birds. There was a pastry shop that have used the same 40-year old recipe since the day it opened for business, and even a car repair workshop that doubled up as a daycare for the child of a single parent who had to work part-time.

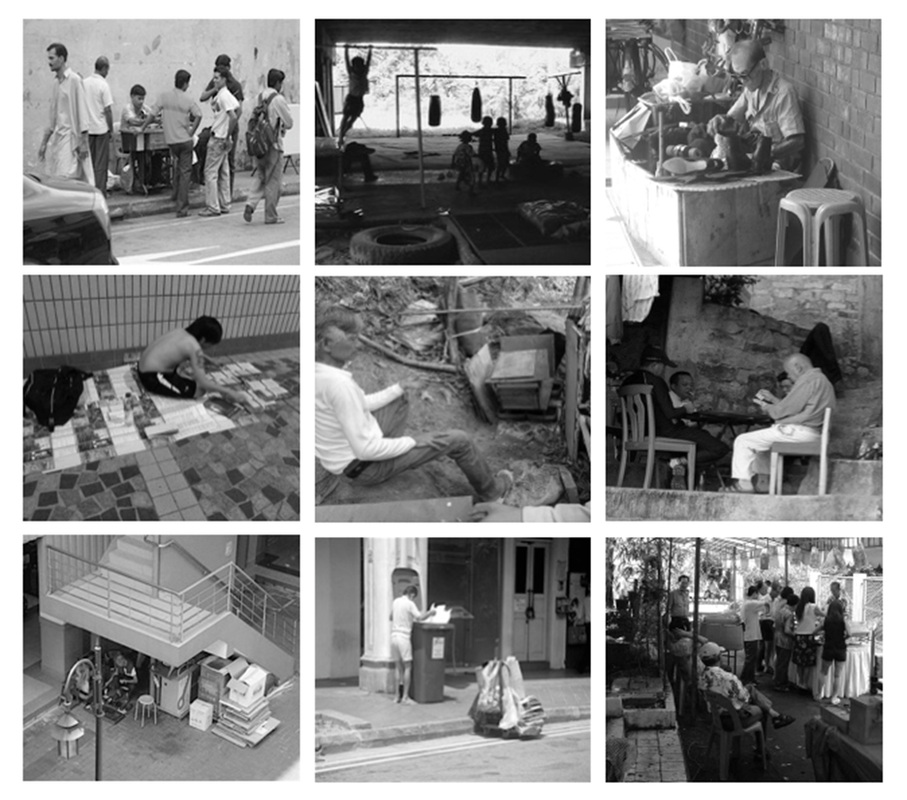

The city is filled with people engaged in a wide variety of daily activities every morning- going to work, buying breakfast along the way, delivering goods and services, cleaning the shop front, waiting for the bus, etc. These activities occur repeatedly each day without fail, to the point of being involuntary like breathing. But their repetitions also instilled a sense of dullness and monotony. What happens when we reframe these ordinary activities as various forms art, ranging from public sculptures to performances? Will we begin to see and value them differently? Taken from Hong Kong one morning, the various objects and human activities reveal the rhythm and relationship of space, objects and people in the fast- moving city.

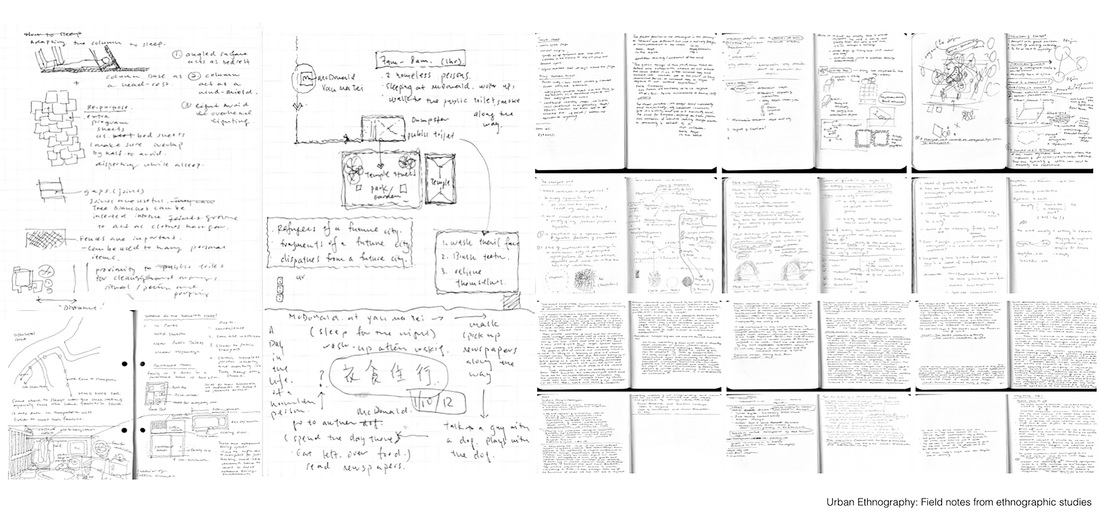

A selection of field notes taken during my multi-year research on the lives of urban dwellers living along the margins of society in Asian cities.

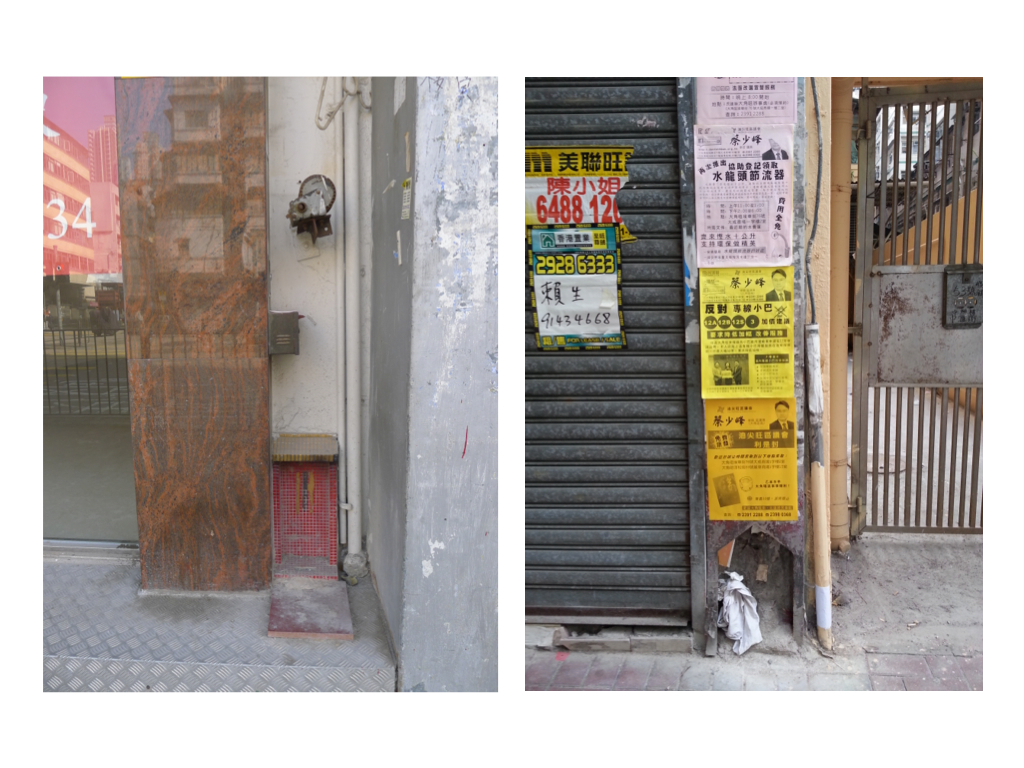

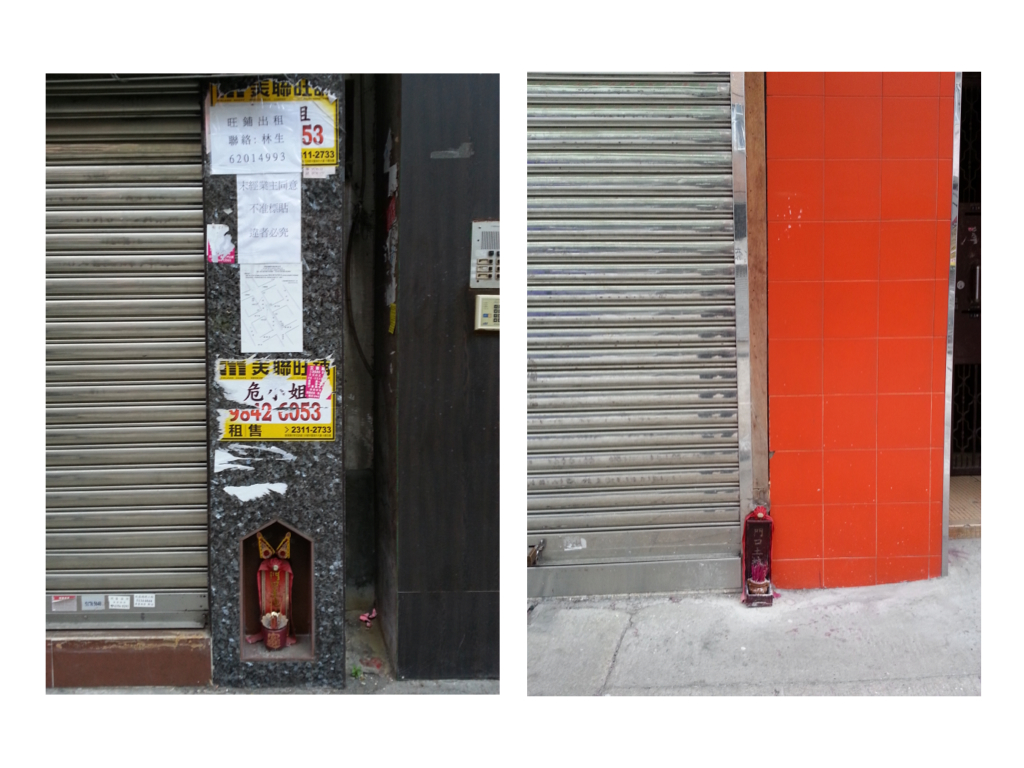

My recent work revolves around the term Lesser Urbanism. It is inspired by William Morris’s 1882 essay The Lesser Arts of Life. Lesser Urbanism curates, examines and presents aspects of urban life in high dense cities that are overlooked or ignored. Their presences are often negotiated, contested, and sustained along the margins of society. Although urban development is progressing at a relentless pace in Asia, I find there are still the vestiges of traditional rituals and local customs subsisting alongside and in quiet resistance against the process of globalization and gentrification. To disclose and celebrate these local cultures and alternative spatial practices where resourcefulness, creativity and sociability are called upon to overcome unfavorable situations and material scarcity is imperative in Asia, as more and more vernacular knowledge and places are erased and forgotten. My on-going research project on the Wah Fu informal public space in Hong Kong is one such effort. (http://www.studiochronotope.com/informal-religious-shrines-curating-community-assets-in-hong-kong-and-singapore.html). My interest in Lesser Urbanism transpires through a slow, deliberative journey reaching back to my early graduate work at Cranbrook, where I was concerned with the rules of forming and how elemental forms circumscribe space and propagates an emergent order through a bottom-up process of placement, aggregation, extension and configuration. In Lesser Urbanism, I am equally keen to articulate forms of individual and collective judgment and governance, both tacit and stated, as well as social conditions that give rise to, scale out and sustain localized spatial organizations. They herald a novel urban experience, alternative strategies of configuring spaces and make visible a vernacular poetics that are more representative of our contemporary splintered and tangled lives heightened by increasing contingency, scarcity and entropy. When walking around Hong Kong, one can still find the presence of the 地主神 or Landlord Spirit altar at the lower corner of many shop fronts. The 地主神 is there to bring business and good fortune to the shop owner. Although the original 地主神 altar has two lines of inscriptions that declare the protection of the owner’s wellbeing and to bring more businesses, recent ones are simply reduced to a single line that says門口土地 財神 or Fortune Earth God At The Front Of The Door. Some 地主神are well kept and there are special niches designed to house the altars. There are others that are simply placed in front of the shop corners. A few 地主神 were seen sharing the altar space with a neighboring 地主神, with the Sky God or are squeezed among other objects outside the shop. And there are those that needed a bit of cleaning while a few have fled the shop front when the shop owner relocated to another place or the shop closed down due to poor business. Perhaps the ability of the 地主神 to bring new businesses varies or because the shop owner did not take good care of the altar. Either way, the empty niche and the remnants of what used to be the abode of the 地主神 conveys a poignant picture. With the help of a social worker from the Salvation Army, I managed to interview a group of homeless residents who made the Cultural Center in Hong Kong their shelter for the night. " You can make a shirt hangar by using a twig. The gaps between the tiles are big enough to slot them into the space. But you need to use a fresh one and some efforts are needed to bend it to form a hook." "I use the old program pamphlets from the Cultural Center and spread them carefully over the floor. Important to have at least 2 layers to prevent the cold from seeping through. I overlap the pamphlets to make sure my 'mattress' is not scattered all over during the night. Don't worry, the pamphlets are for events that have already passed and we make sure they are disposed off in the morning. We don't want trouble from the authorities. We are also doing the earth a favor too by recycling these pamphlets!" "The columns of the Cultural Center are excellent for us. We can slide in-between the two columns and the angled floor is like pillow. I wonder if the architect thought of us when he designed the center?"

"If I'm in a hurry, I'll just take a medium size cardboard and slide my body inside. It's like a blanket. I'll sleep in-between the columns to get some protection from the wind. Most important of all is to protect your chest! I interviewed some Hong Kong residents who spent the night at McDonald's. They were an interesting group of individuals who, by choice or circumstance could be found in the 24-hr fast food restaurant for different lengths of time.

" I don't have a home. I usually spend my nights in the internet cafe if I get paid. There I can surf the web, chat online and eat noodles very cheaply. If I'm broke, it'll be the park or McDonalds." "I come here every night. It's cleaner and safer. I even see women sleeping here! And it's definitely warmer during the winter months." "Here I can get a cup of water from the counter staff. Some are nice as they know we have no money. But I also try not to create trouble." 'Why McDonald's? The use of the toilet of course. It's convenient especially for me. And I can also wash up in the morning" "I'm not here every night. I can't sleep so came here to get something to eat and read the newspaper." "Some staff can be quite mean. They will deliberately switched on the lights at the corner of the restaurant even though no one is around or they will put up some barrier to prevent us from using the space." "You need to know how to sleep here. If you lay your head on the table, they will come wake you up. So you try to sleep upright. Not easy but you get used to it." "I have a few McDonalds around the neighborhood where I go to each week. I try not to stay in the same restaurant every night because they may not like it. So I'll rotate my stay and so far it has been OK." "I just finished work, so came here for some food before going home. Yes, I see many who seem to be using this place to sleep. I'm fine as long as they are considerate. It's empty anyway." Professor Siu sent me this wonderful picture of an informal shrine set up by the protesters. He wrote, "The Guan Gong statue was worshiped by both the Police and the Triad Societies… And the citizens used this to counter their power against the protesters.

A fascinating observation by one of the Pro-Democracy protestors from Hong Kong as described by the South China Morning Post.

"It's an enjoyment to be here. Here in Admiralty, you can find a more humane Hong Kong where people are helping each other out every minute," says Cheung. "There is no noise from traffic, but birds singing. You see trees, you live a way slower pace of life ... it's beautiful," he says. "It gives people an opportunity to experience the preciousness of public space." Retrieved October 5, 2014 from http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1609580/live-chinese-university-urges-students-leave-thousands-gather "I lived and studied under the path (where the banking occurs) of the Rwy 13 Approach back then, it was noisy enough to interrupt our teacher every 3 minutes for say 20 seconds. And there was "always" a plane departing in between the 3 minutes interval, although not as noisy as it flew over towards the sea. I also noticed that, the local players, namely Cathay Pacific, usually made the approach path a bit wider and a bit more towards the hill so they can have a longer final and a shallower angle of turn, then the published procedure. Also rememered I can occasionally feel and hear the wake turbulance even from a meduim weight aircraft, from my school playing ground in the good old days...Long live Kai Tak."

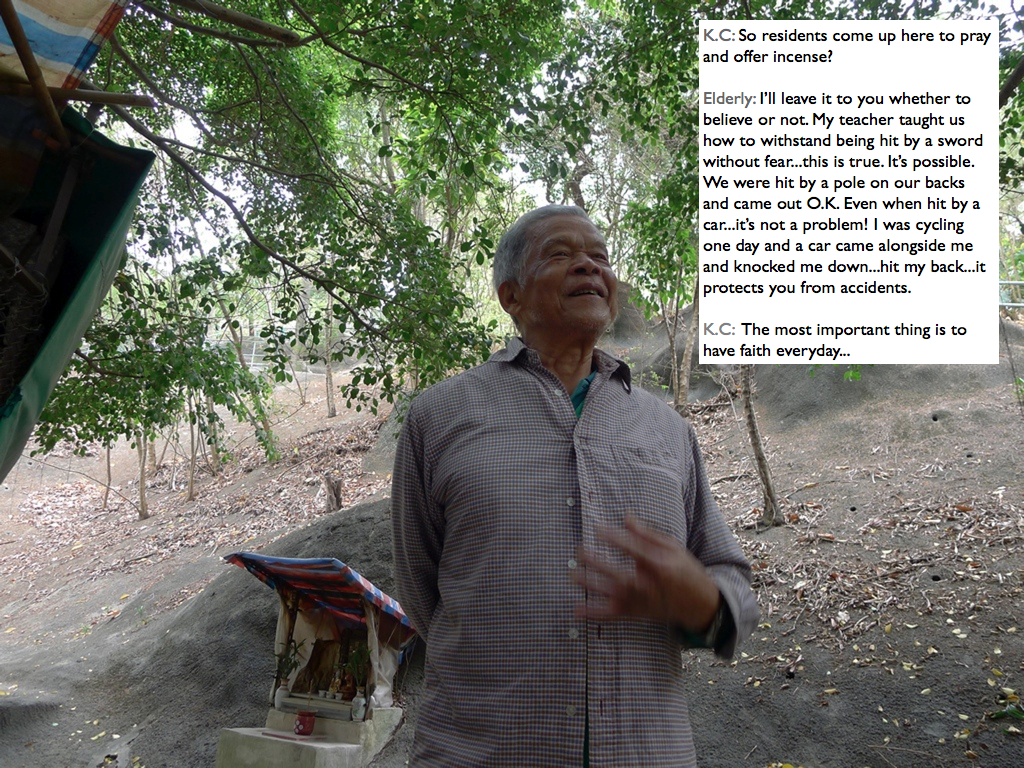

Accessed March 15, 2010, http://www.liveatc.net/forums/listener-forum/kai-tak-old-hong-kong-airport/5/?wap2. Based on the above account, In a typical elementary school day of 6 hours (360 minutes), the teacher stopped a total of 40 minutes. In one school week of 5 days, the teacher stopped a total of 200 minutes or 3.33 hours. In one month of 21 school days (assuming no public holidays), the teacher stopped for a total of 70 hours. The story of the Wa Fu community space began almost 30 years ago. The place was a destination for residents living in the near by housing estate to leave their statues of porcelain deities when they relocated or when the religion was no longer practiced by the younger generation after the passing of the elderly family member. The stepped profile of the ground leading to the sea is an ideal site to place the deities. They are secured individually by a layer of cement to prevent them from toppling over during a typhoon. Through time, a sea of porcelain deities slowly emerges and are they cared for by a group of elderly residents. Some deities are protected by simple shelters while others share their spaces with toy figurines that were also left here. A self-constructed shelter serves as both a community space for the elderly and for them to keep their belongings. A well close-by provides fresh water for cleaning after taking a dip in the sea. We were told it is a popular activity among the elderly and younger residents. Some come for a swim early in the morning before heading off to work.

The hillside informal shrine in So Uk Estate is connected to a larger network of elderly walkers and informal social spaces. The shrine is situated along a path that winds up the hillside, which is a favorite spot for the mostly elderly residents and housewives to engage in their morning walks and exercises. The shrine is often a stop over for the residents. They would offer incense or a simple prayer at the shrine on their way up or down the hill during their morning exercise routines. Besides exercising, the residents have also undertaken small, self-initiated actions along the various exercising spots; such as plant caring, building of small concrete steps to link disconnected parts of the hillside and allow a safer walk up the hill, introducing resting spots, setting up support facilities for the morning exercises, and repairing broken planters. Water for the plants is collected from the natural run-offs from the hill in small pails and buckets. The So Uk Estate shrine and the adjacent exercising spots are excellent examples of bottom-up initiatives in place-making. It makes a strong case for allowing urban dwellers to take control and have the opportunity to shape their immediate spaces in the city rather than top-down initiatives that often miss the point and cost much more than they should be.

Strategically placed street advertisements along a sidewalk and crosswalk in Hong Kong. The steel barriers are re-purposed as supports for the advertisement boards.

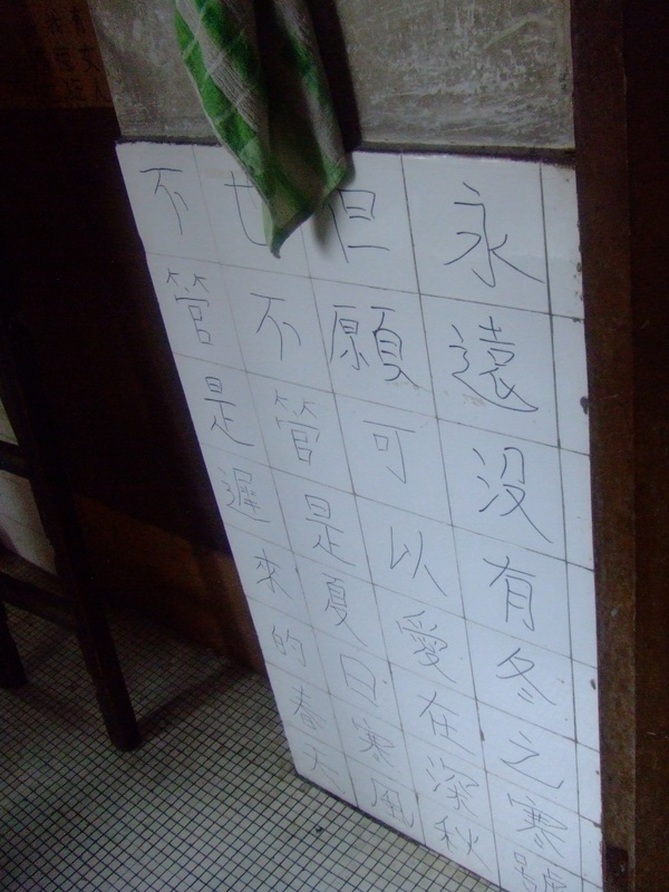

Despite the unpleasant living conditions in a partitioned apartment in Hong Kong, a resident composed a poignant poem on 32 square ceramic tiles. Each character and stanza fitted nicely within the given space.

An interesting feature of highly urbanised and Westernised Asian cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore is the occasional Chinese religious shrine lying next to a tree, in a discrete section of a public space or at a certain road junction. Some of them are erected by individuals or groups to express their gratitude for an answered prayer or to ensure a harmonious environment. Others begin when the altars of “house gods” or religious statues are “left behind”, because the previous owners have relocated to another home, or because the younger generation no longer observes the same religious practices after the passing of elder family members. To the older Chinese generation, religious statues formerly acquired for home collection and worship are not to be discarded disrespectfully. They are either given to another “caretaker” or are relocated to auspicious places, such as under a tree or beside a roadside rock.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed