|

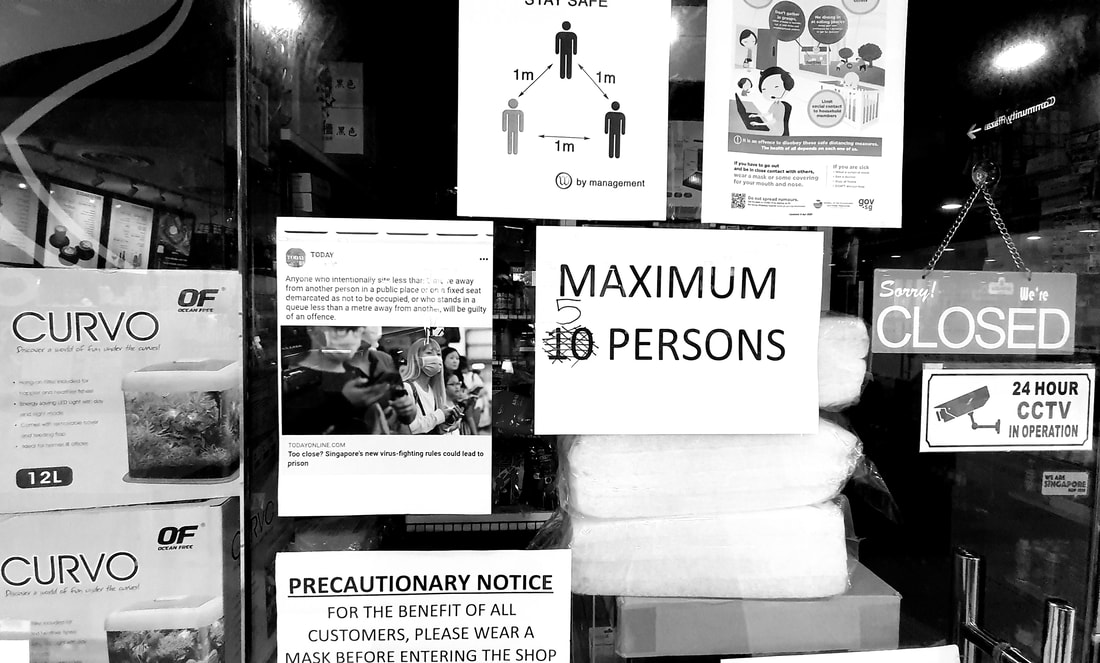

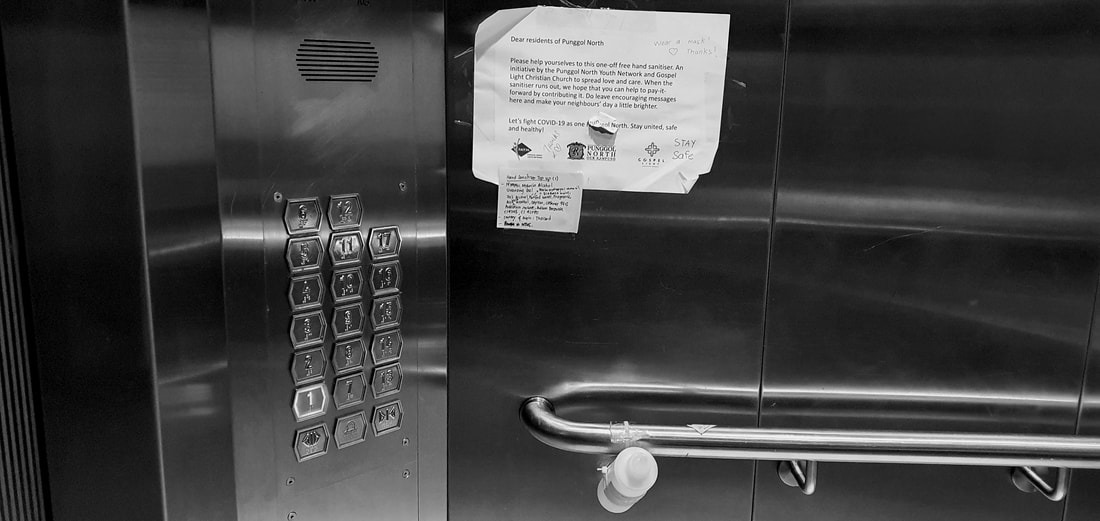

The Covid-19 pandemic has challenged and uprooted our lives in ways unimaginable on a global scale. When cities are locked down for an extended period and their inhabitants told to stay home, these unprecedented social restrictions are counter to our fundamental way of life. For personal safety and social responsibility reasons, careful considerations now intercede simple, everyday interactions that we take for granted before the pandemic.

My 5 min presentation for the event on Sep 16, 2017 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

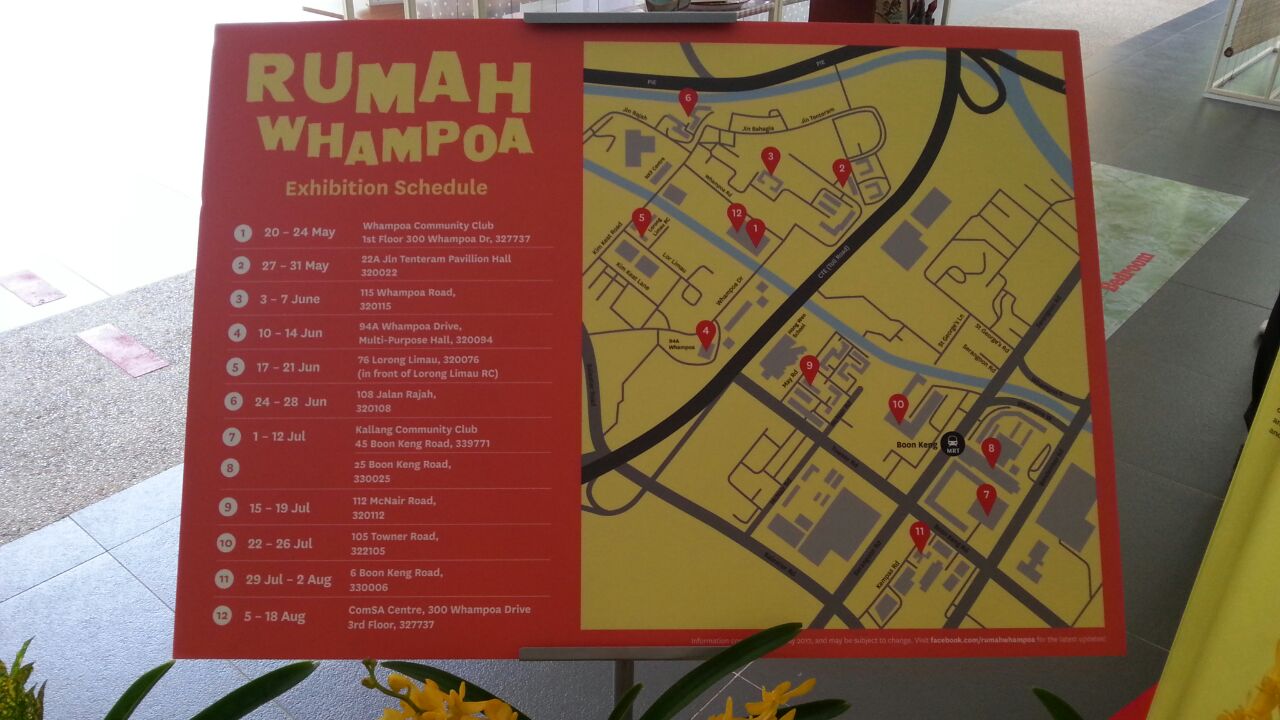

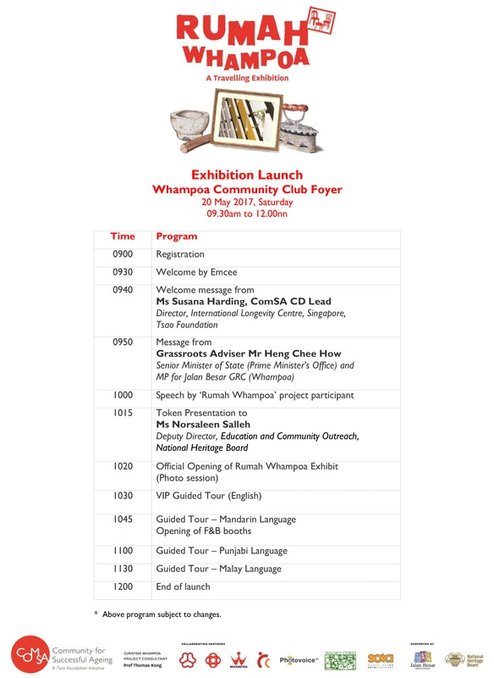

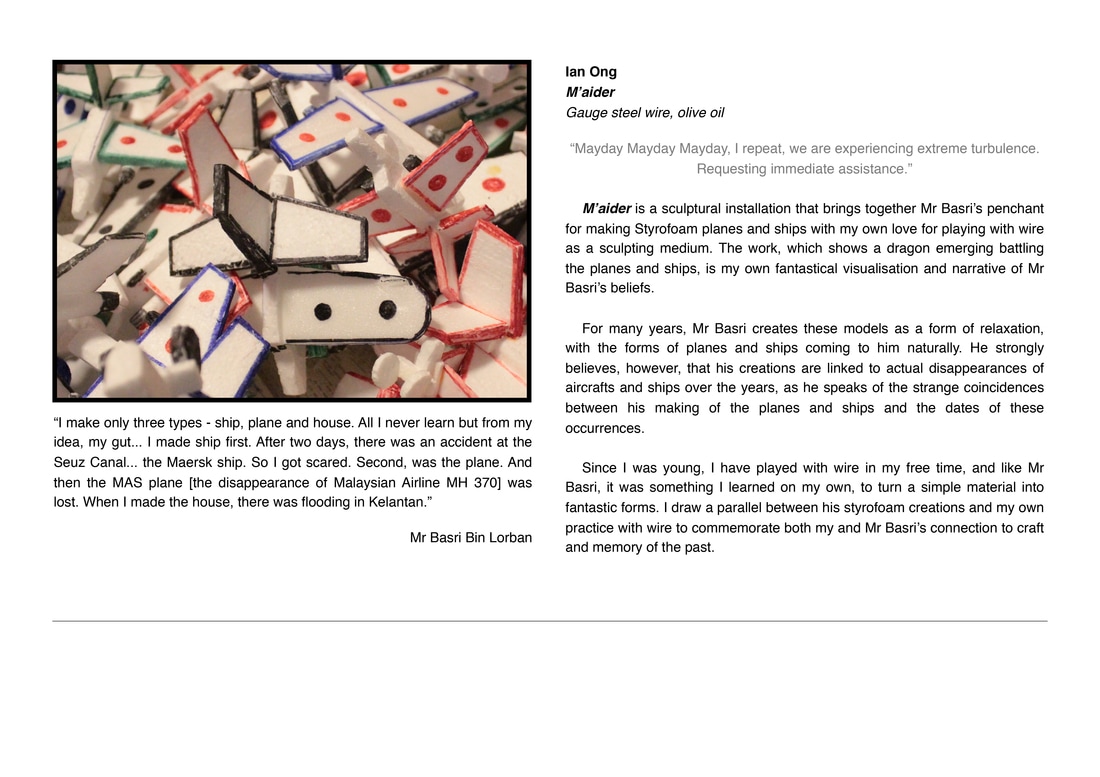

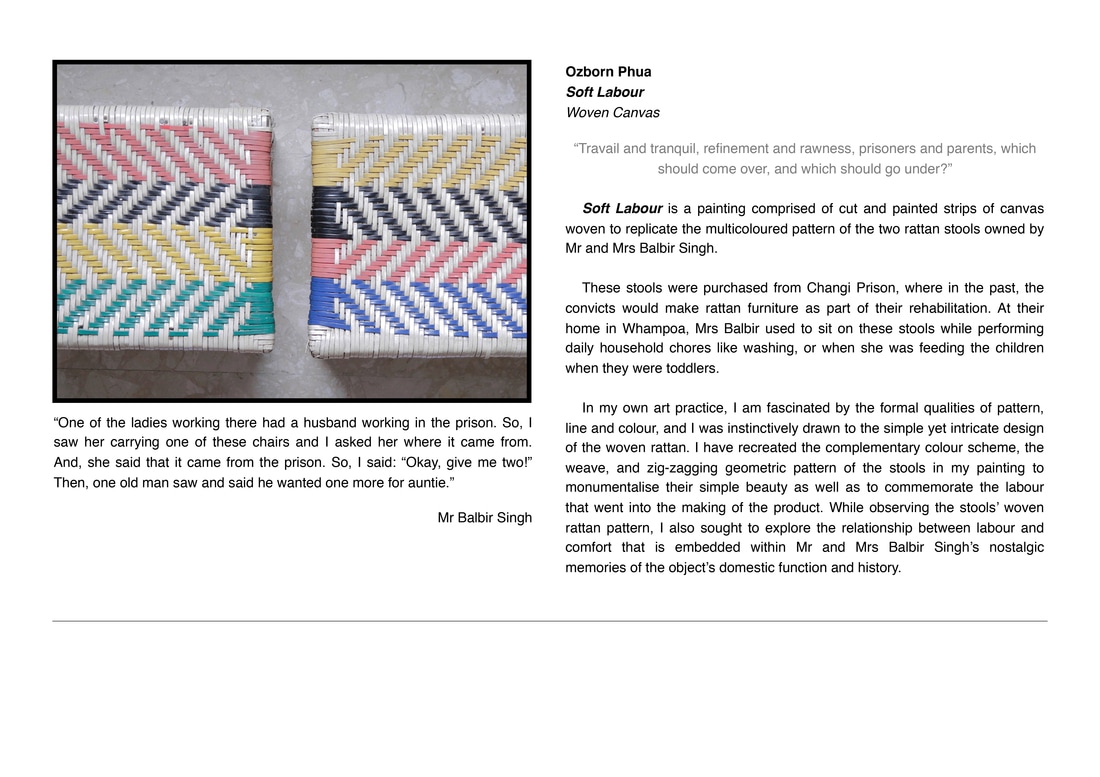

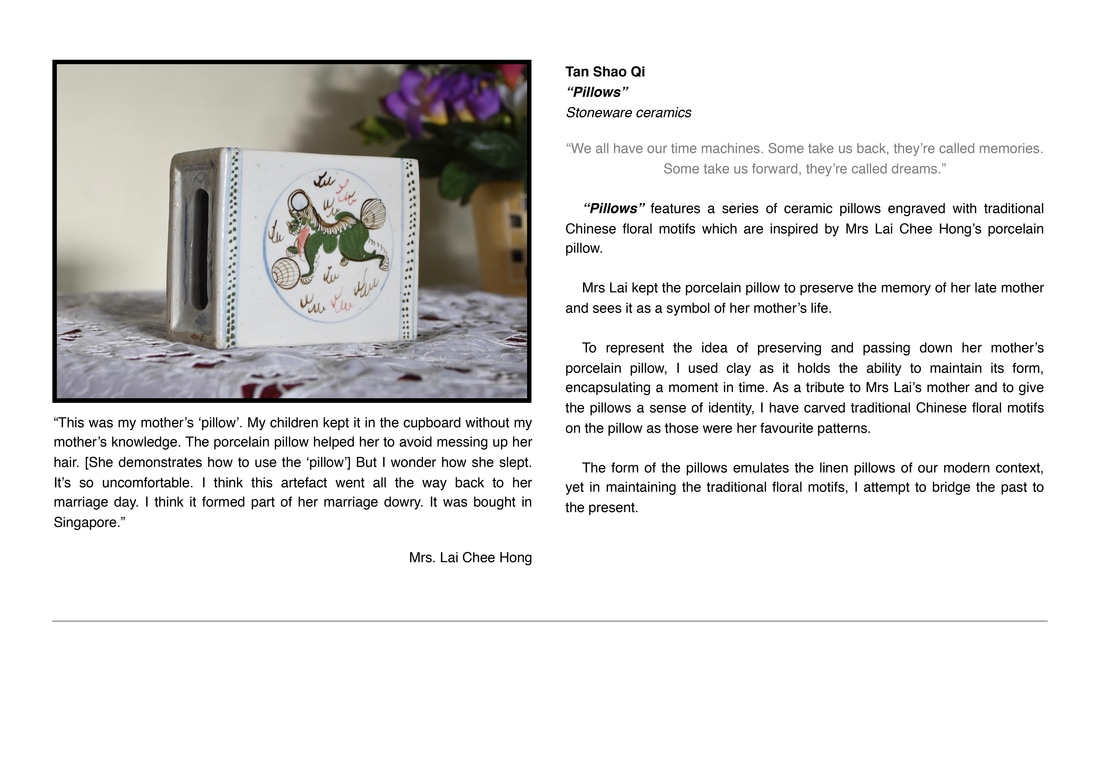

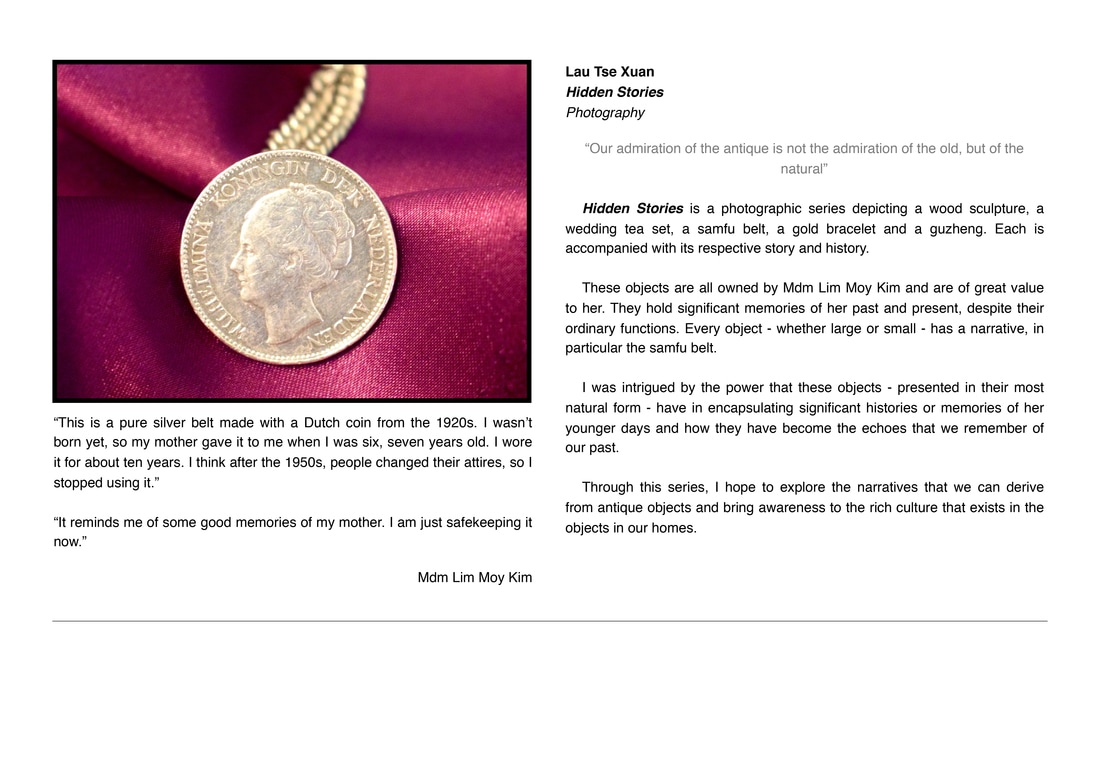

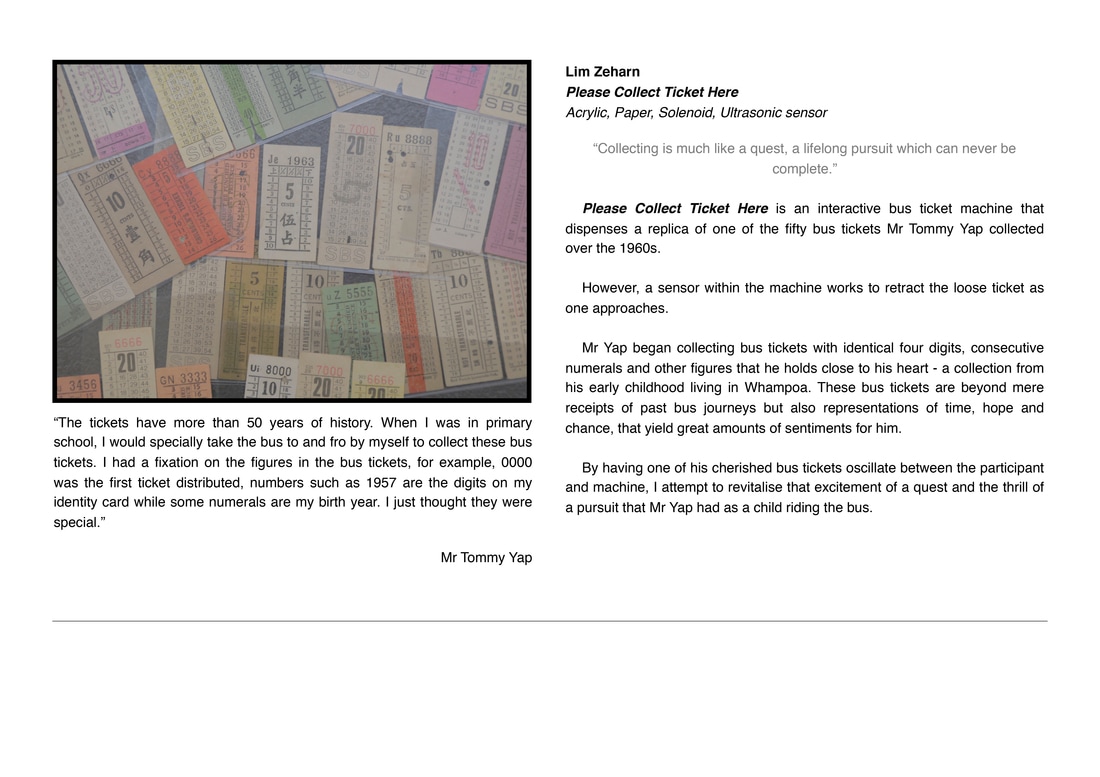

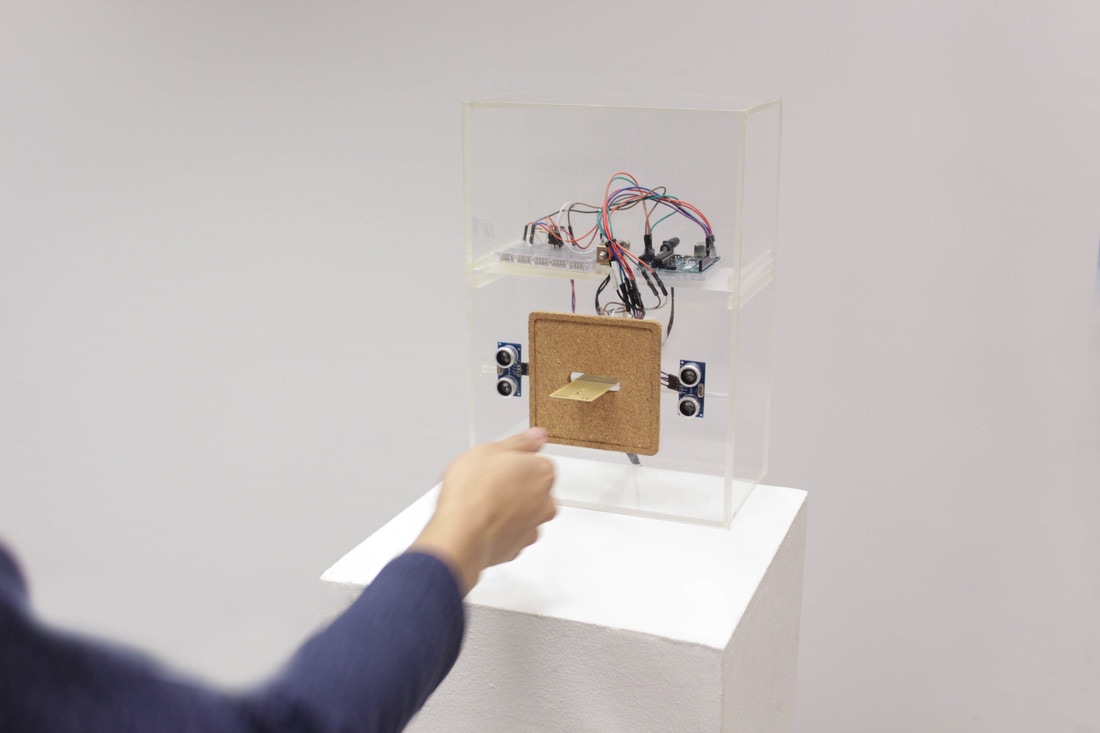

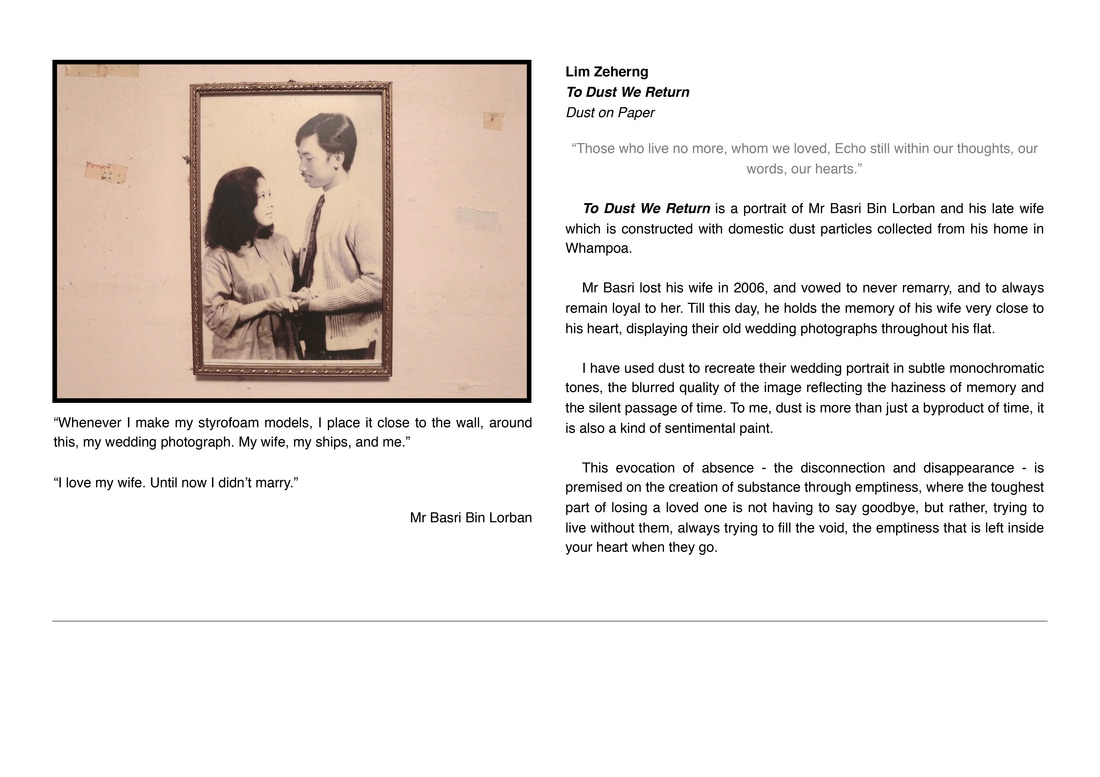

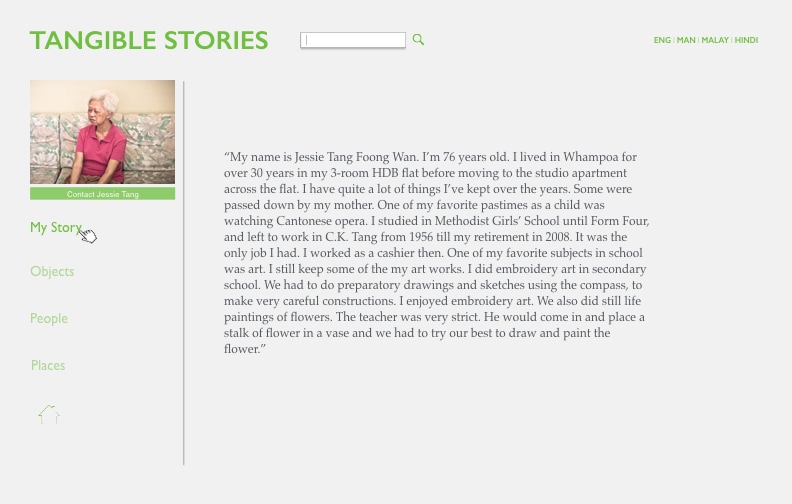

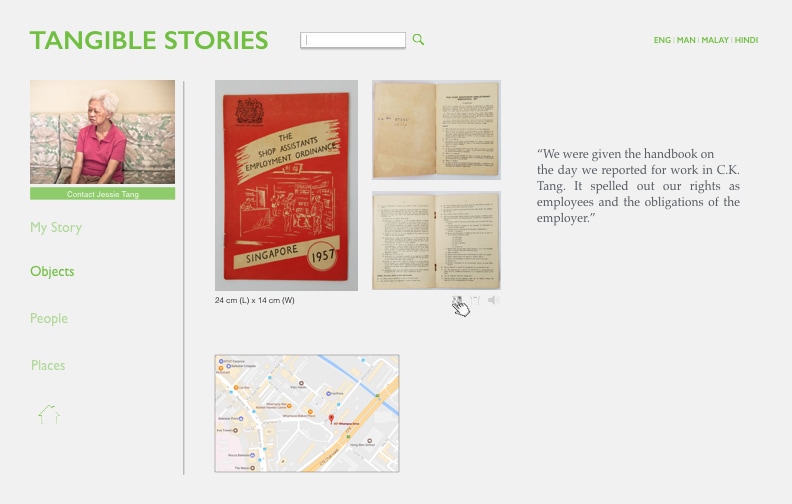

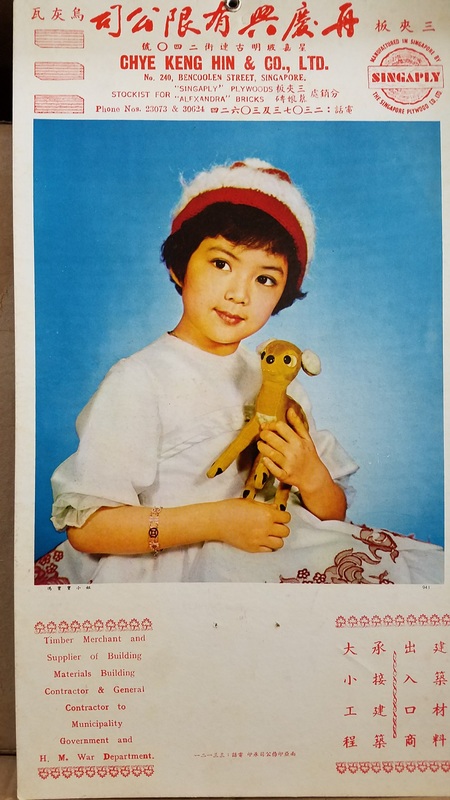

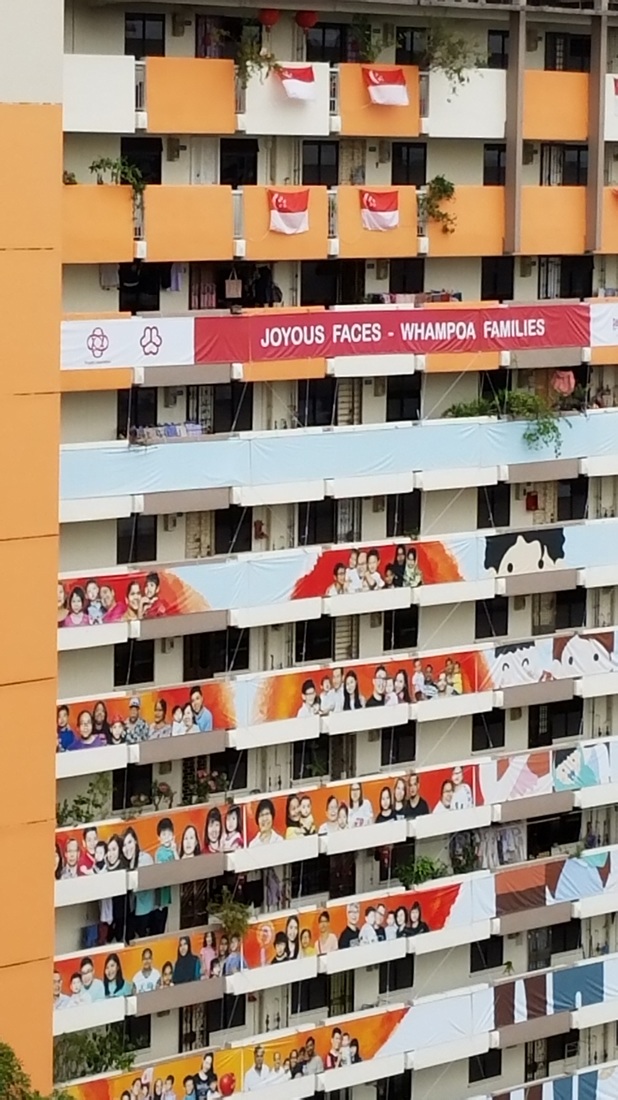

The airport fascinates me as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Seldom do you find gathered in a building such a diversity of nationalities and cultures. In this slide, you see the Goddess of the Sea, Mazu and her 2 Heavenly assistants taking a business class flight from China to Malaysia for a religious event. They were issued boarding passes too. Future innovations will need to recognize and address the needs and experiences of a diverse group of travelers and users. In Singapore, the Changi Airport is a destination for the young and old who come to the airport for a variety of reasons. So much so that Changi may be the only airport that has so many signs discouraging students from studying. Changi is more than just an airport to the locals. It is a third place, a term coined by Ray Oldenburg to describe a place that people gather that is neither a home nor the office. First impressions count. The Copenhagen Airport is a showcase of Danish design. On the other hand, during the design of the Changi Airport in the 1970s, the Prime Minister then instructed the planners to plant rows of rain and palm trees along the highway leading from the airport to the city center, and that they be well maintained, for 2 reasons. First, it conveyed to arriving visitors that this is the tropics, and secondly, a signal to potential foreign investors that the city-state is well managed and the right place to invest their money in. This first impression was designed to reach a high point when the towers of capitalism, hidden by the trees, unfolded before your eyes as you reached the highest point of the Benjamin Sheares bridge after a 15 min taxi ride from the airport. Vice versa, the experience of the airport starts before arriving at the terminal. The in-town check-in service in Hong Kong is a good example. It gives back some control of time to the travelers who have to negotiate an environment that encourages consumption yet tightly controlled and surveilled. I believe designing the experience before and after the airport is as important as the airport itself. Rumah Whampoa presents two community engagement projects--Tangible Stories & Photo Voice—which the Whampoa senior residents participated in over the last six months. Conceptualized by various art collaborators residing locally and overseas, Rumah Whampoa exhibits a collection of verbal and visual narratives about the lives in Whampoa, as told by its senior residents. In Tangible Stories, the residents shared their personal stories of objects that had stayed with them over the years, and which they have kept as they moved into Whampoa. In Photo Voice, the residents learnt digital photography and in turn, presented their view of Whampoa through the photographic lens. Curatorial Concept The exhibition focuses on the idea of welcoming others into the lives of these senior residents. Styled with materials that harkens the past and using the concept of a rumah (home), the narratives are clustered by the areas that define activities in the home: outdoor play area, cooking/eating area, bedroom/study, etc. At each of these areas, the verbal and visual narratives captured through the two projects intermingle. The exhibition operates at two levels, presenting snapshots and anecdotal accounts as well as inviting the audience to be curious and to pick up some of these objects, further discovering some of the personal histories associated with them. Designed to be portable, these modular clusters are reconfigured at each new site which hosts the exhibition. In that way, a new variant and interpretation of “Home Whampoa” is created each time. Text by Jacelyn Kee. Exhibition design by Fellow. http://www.wearefellow.co/

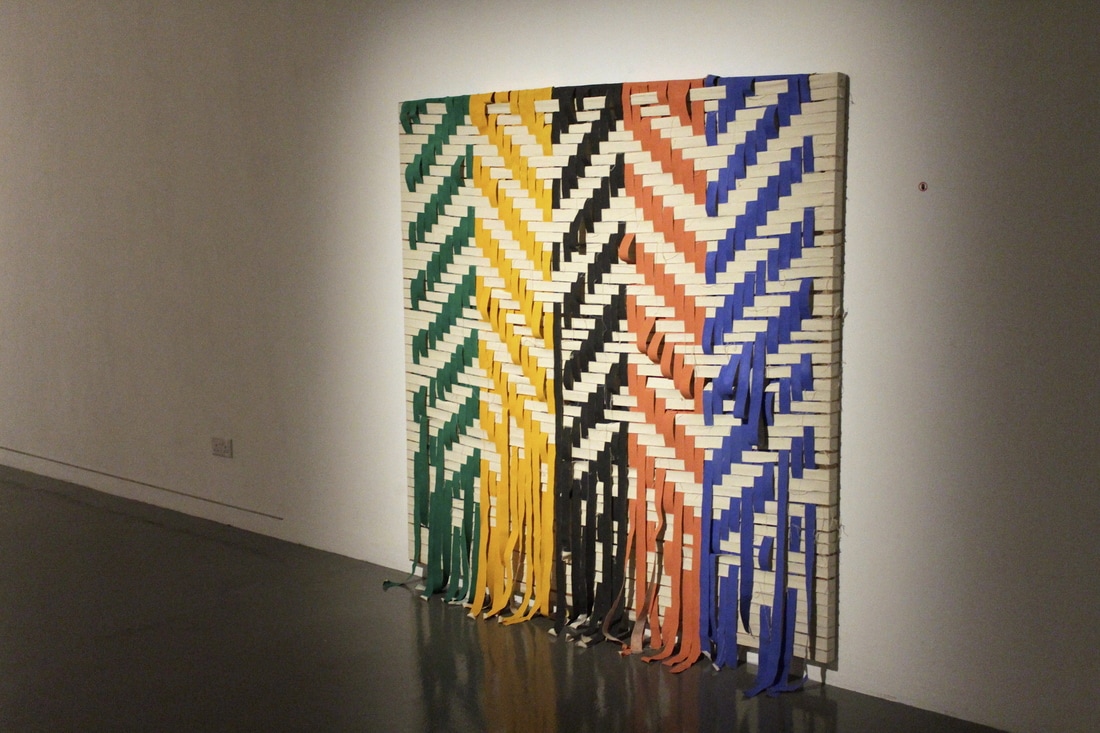

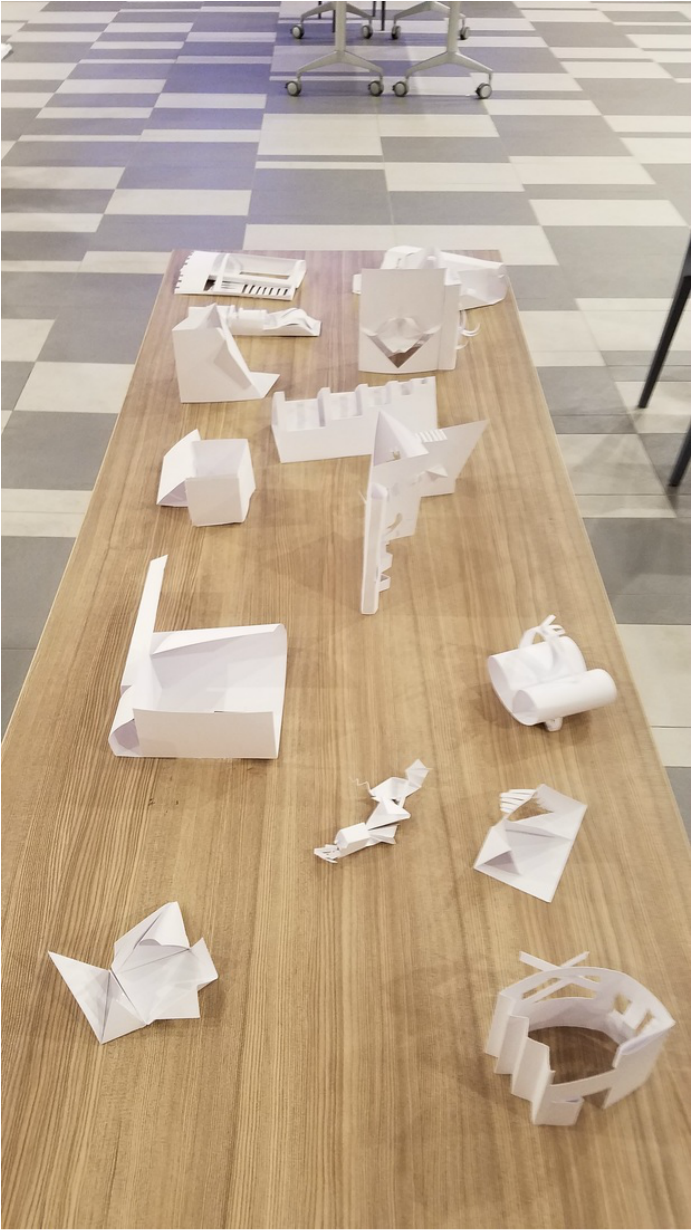

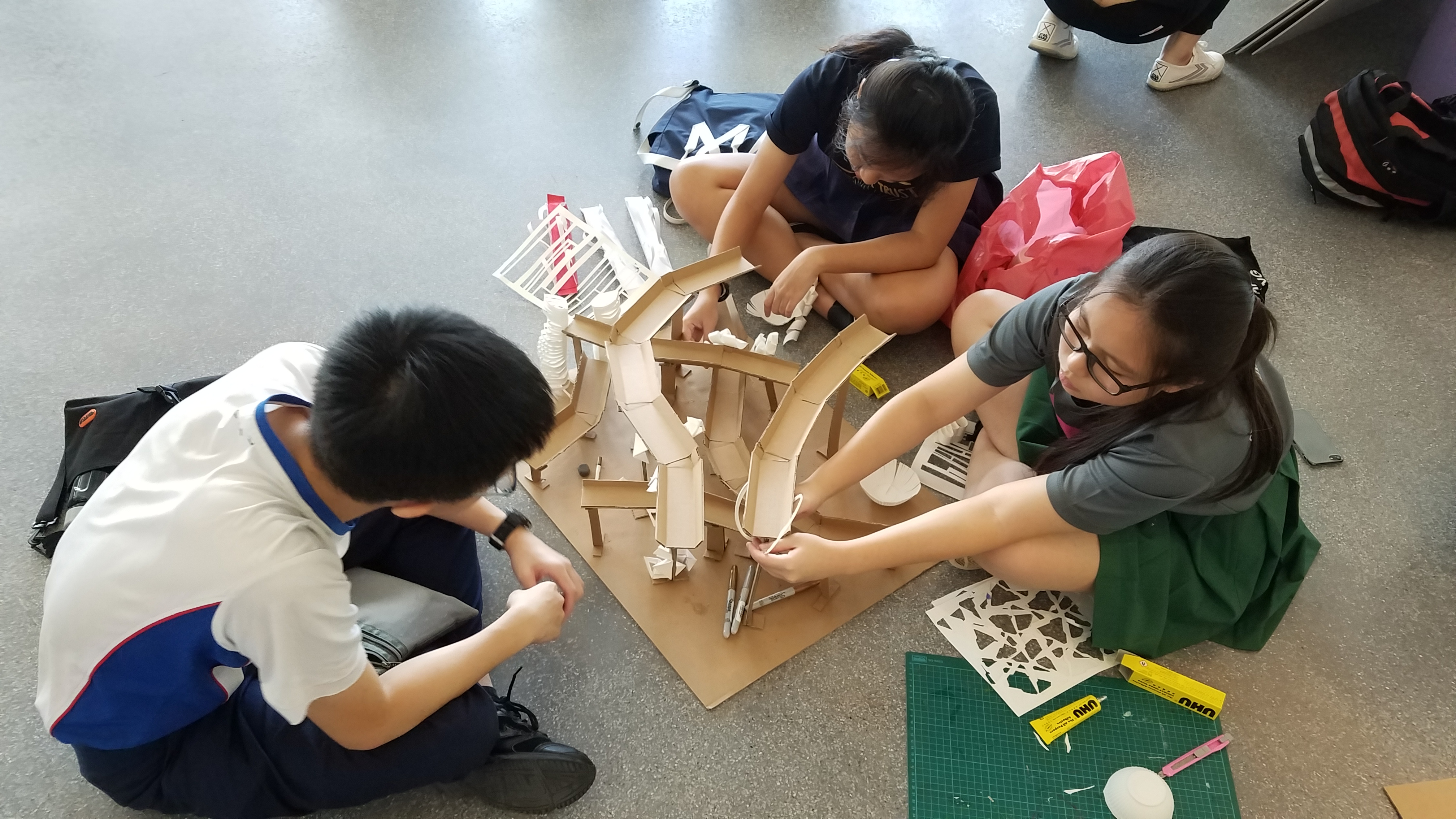

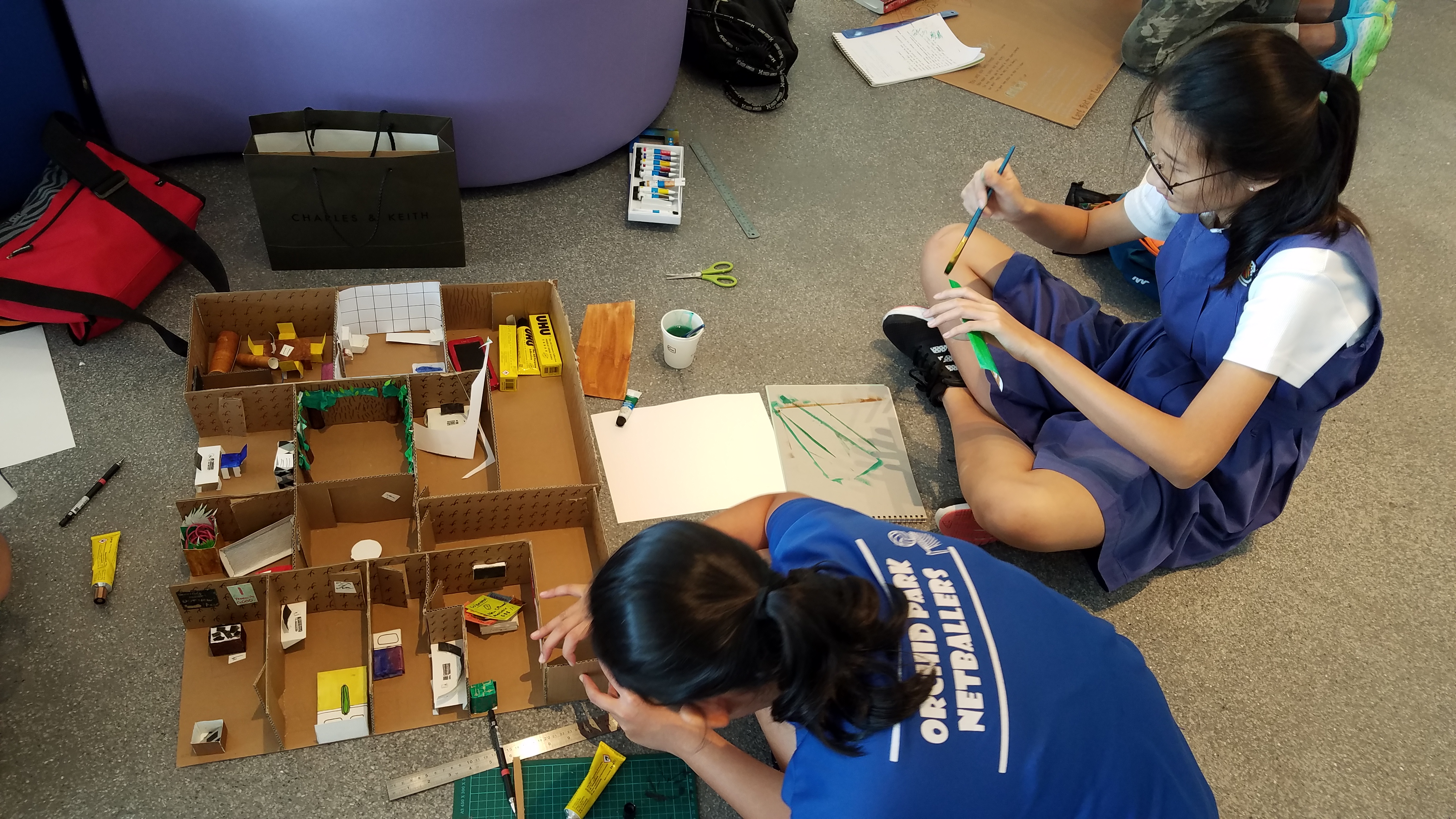

Tangible Companions is a project to develop contemporary companions for a number of old artifacts that Whampoa residents have fond memories of. From January to April 2017, high school students will draw from the interviews and images curated from the Tangible Stories project to develop their proposals. By describing the outcome as a companion, the project aims to encourage a multi-scalar and an interdisciplinary inquiry grounded on an empathic creative response to the artifact’s history, qualities as well as its affective relationship with the owner. The project is conceived by Thomas Kong and led by faculty members David Gan and Vincent Leow from the Department of Visual Arts at the School of the Arts, Singapore (SOTA). Exhibition of Completed Works at The School of the Arts. Singapore. All photos courtesy of SOTA. "...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears."

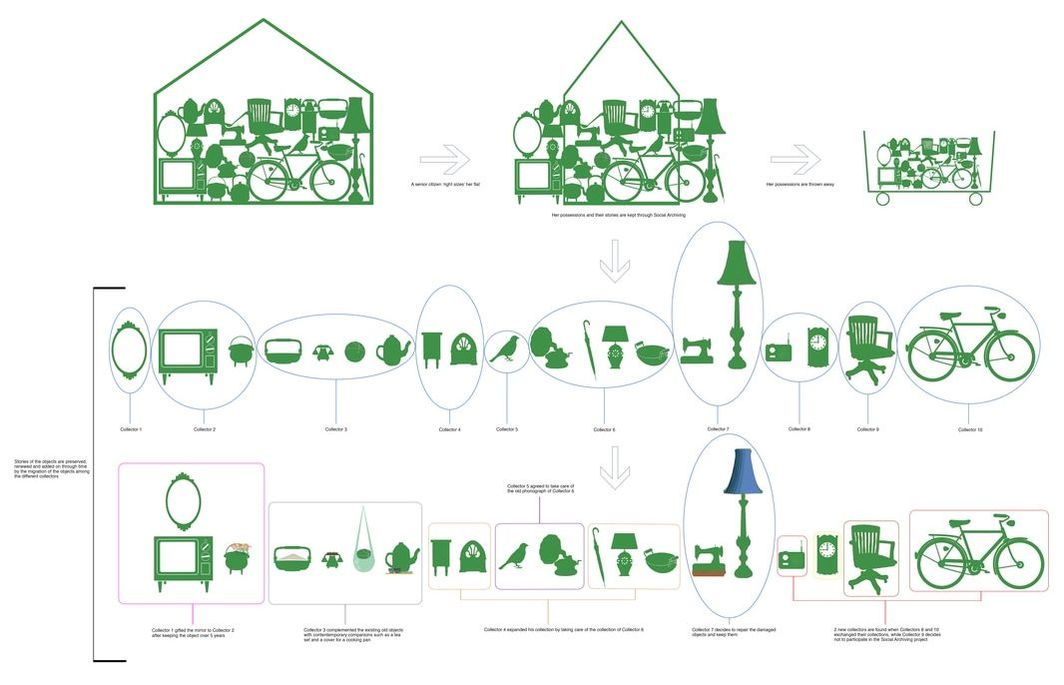

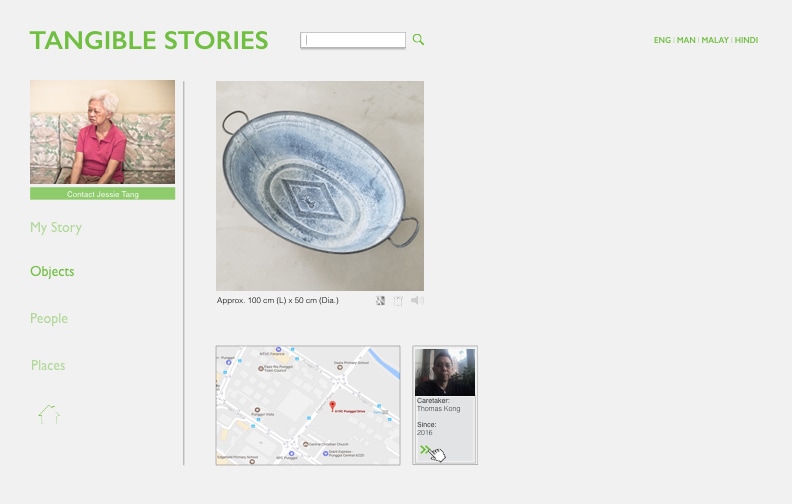

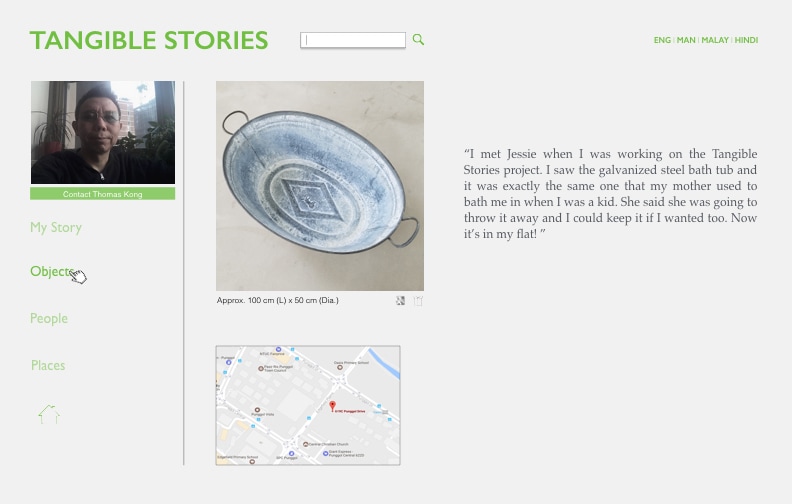

Lewis Hyde. The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World. Social Archiving explores a new form of archiving that combines gift giving, safekeeping, curating, placemaking and a renewal of the life of a collection through a simple in-person ritual and a digital interface for sustaining the social life of the collection nationally and beyond. I conceived of Social Archiving as a new model of caring for objects and ephemera that carry cultural and heritage value. It is a platform for intergenerational learning in-place and online, public stewardship and the building of a personal legacy through the sharing of the stories related to the archived materials. Social archiving was motivated by the diminishing size of an elderly’s home and a rapidly aging population in the city-state. Social Archiving draws from the rich tradition of archiving as an art form and differs from current institutional model of archiving in the following ways: 1. It is interdisciplinary. The process in itself constitutes a participatory form of art-making and sharing. 2. Although Social Archiving has a precedent in the rich tradition of archival art, it does not rest purely as a one off art project. Social Archiving helps in the crafting of interactions and relational structures in the design of spatial strategies to address contemporary urban concerns. Specific to this proposal are the issues of aging in place, personal legacy, identity, community forming and the spaces that support them. 3. It relies on the interest, passion, care and housing offered by a community of volunteer archivists/collectors/curators instead of the control and management of an institution. 4. It promotes social interaction, both digital and in real time in the archival process. 5. It encourages active, creative re-interpretation and curating of the archived materials that extends beyond the passive role of offering a storage space. 6. It recognizes the role social media plays maintaining contact between archivists, between the original owner and the new collector, and in the organization, dissemination and sharing of the archived materials. 7. It permits the transferring of the archived materials if the new collector agrees to the role and expectations. 8. It is a scalable process that can range from an intimate social setting to a large, community-level interaction. The populations of Asia and Western Europe are rapidly aging and 60% of the world's population is in Asia. Although the project is situated in Singapore, the issues, challenges and opportunities surrounding aging are global while the initiatives to address this rising societal phenomenon are potentially transferable to other nations. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/what-singapores-plan-for-an-aging-population-can-teach-the-us/2015/11/01/f86e9596-7f42-11e5-b575-d8dcfedb4ea1_story.html) Singapore is a particularly important case study because it has one of the world's fastest aging population. Over 80% of its population lives in high rise public housing given the limited land available for development. As the government encourages its citizens to see their apartments as economic assets, it is not uncommon for many to sell, buy and live in several apartments over their lifetimes. Each move generates bigger profits that serve as their retirement nest eggs. Through my encounter with the senior citizens in the course of the Tangible Stories project, I foresee the Social Archiving project can take on a significant role in the social and cultural landscape of Singapore based on the following reasons: 1. As more and more senior residents move into nursing and retirement homes, as well as smaller studio apartments, they are confronted by the challenge of holding on to their cherished possessions acquired over the years. These possessions include furniture, objects for daily use and print materials that house strong memories for them. Unfortunately, many senior citizens have to either sell or throw them away now, especially if they are single or do not have children to pass these objects and materials to. Moreover, some of their children may not be keen to take over their parents’ possessions. 2. Given the unceasing urban transformation and the rapidly aging population in the city-state, many grassroots level memories are lost despite the attempts to collect them through the massive, national-level Singapore Memory Project. Social archiving offers a more intimate platform for intergenerational learning and remembering through the sharing of the stories related to the archived materials. As Arthur C. Brooks in his Op-Ed piece for the New York Times wrote. "One million is a statistic. One is a human story." 3. As more and more studio flats are designed within existing and matured housing estates, there is an urgent need to give greater consideration to the design of public spaces that promotes aging in community. Besides design considerations such as universal access, elder friendly interiors, etc., the provision of spaces and the holding of community events that help anchor personal memories of place can be promoted through social archiving. Partners: Jacelyn Kee; Lee Sze-Chin; Asian Film Archive; Tangs Holdings; Tsao Foundation. I was a mentor to a group of high school art students for over 5 days. Working collaboratively on a theme set by Singapore's Ministry of Education, the students developed spatial propositions via models and drawings. A showcase of the works was held on the last day.

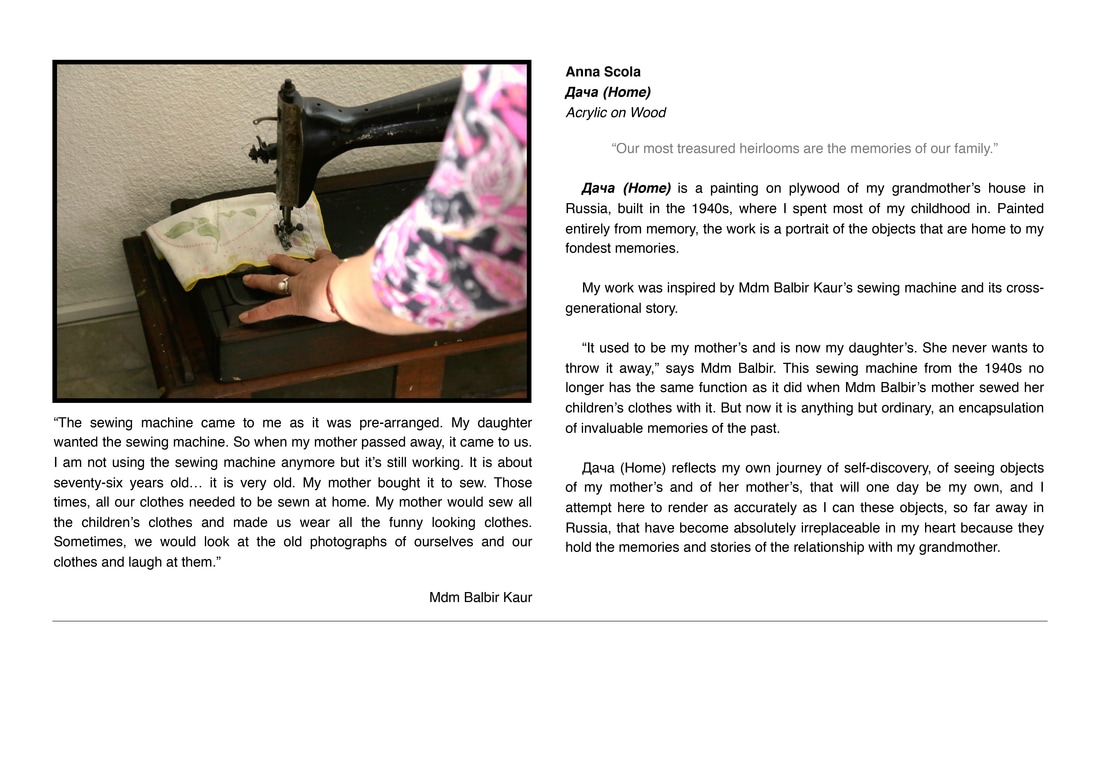

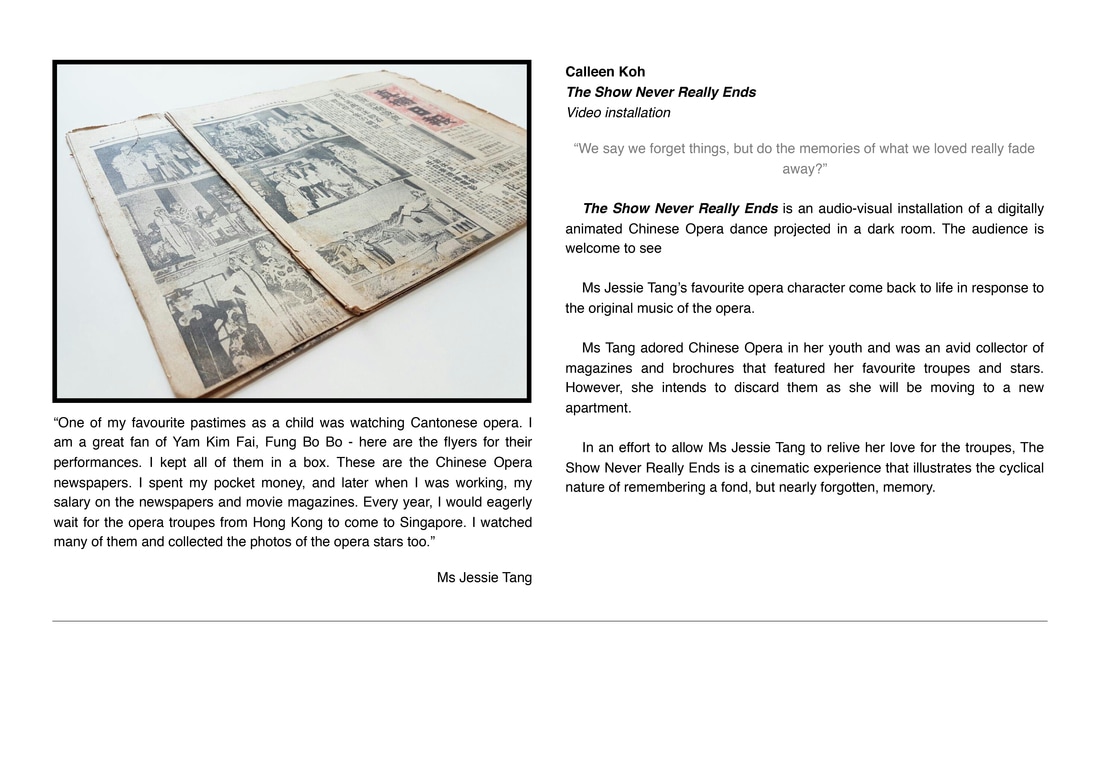

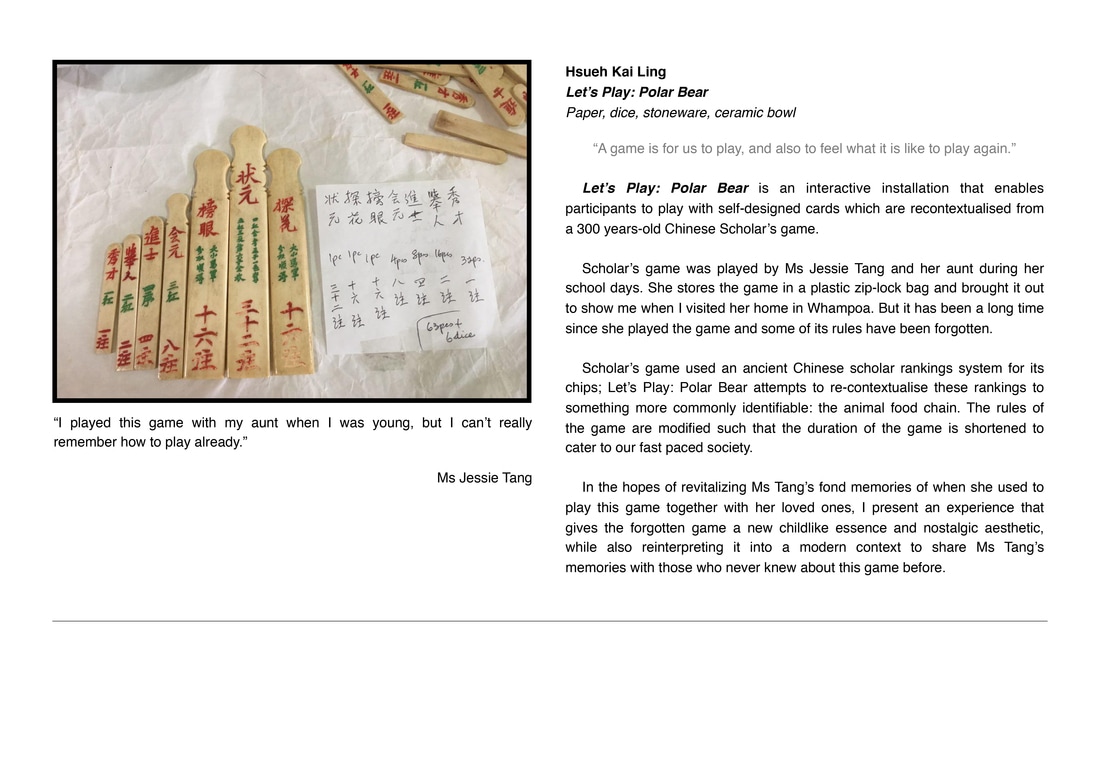

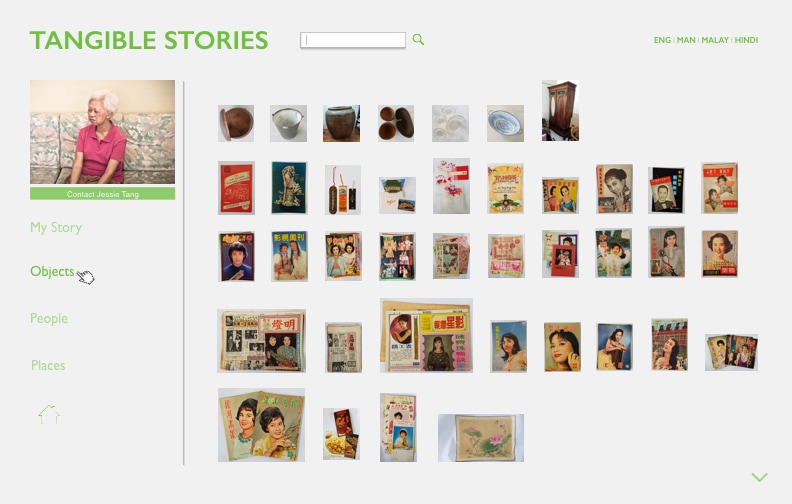

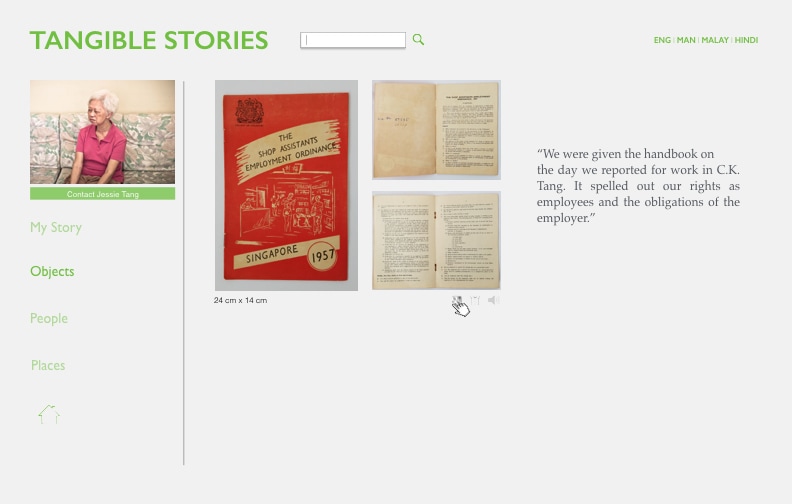

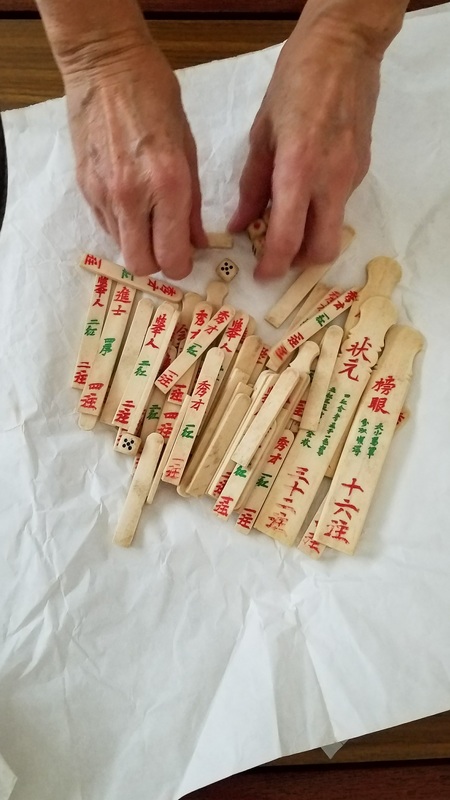

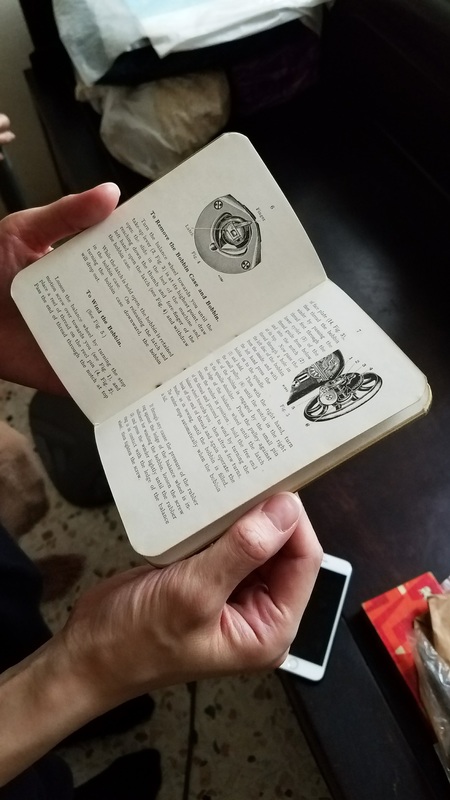

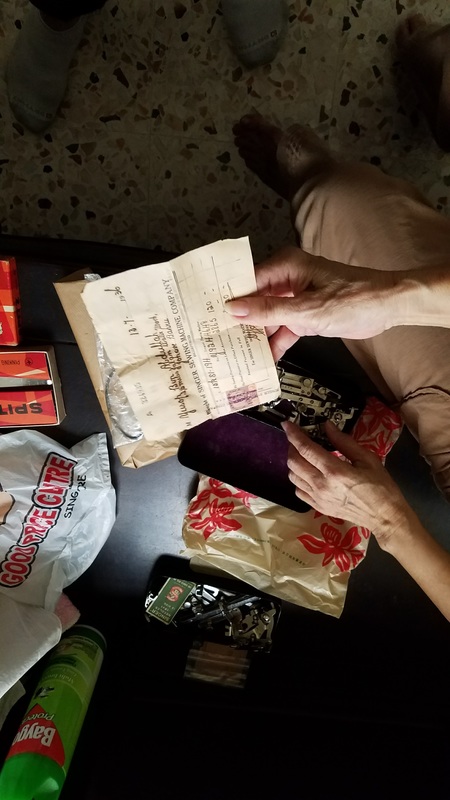

The energy and enthusiasm was infectious. The works carried a spirit of shear audacity that defied my expectations. What to make of a web of bridges that dared to confront our discriminating mind? Who wouldn't want to be in a place of peace and tranquility amidst a sea of noise and distraction? Or be thrown into a reality gameshow that do not simplify our desire for and repulsion of digital connection? And not to forget a tower that fostered sociability over coffee, gardening and a good book. Countless ideas and possibilities to keep us curious, engaged and inspired! I spent several hours over the weekend listening to longtime Whampoa resident Jessie Tang's stories of her collection of objects. They were neatly and carefully kept in photo albums, boxes, jars and wrapped in old newspapers that showed the passing of time. Besides the smaller objects, she has several beautiful antique furniture left behind by her mother. From the retelling of her love for Chinese opera as a young adult and her collection of old Chinese opera newspapers from Hong Kong from as far back as the 1930s, I came to know of a vibrant Chinese opera scene in Singapore. During that era, Hong Kong opera troupes would often come perform in local theaters to an enthusiastic local crowd. Their impending presences were announced in colorful flyers that Jessie fervently collected as well. Besides performing in operas, the artistes also acted in movies. Alongside the Chinese Opera newspapers, Jessie has an extensive collection of old movie star magazines featuring well-known Hong Kong and Chinese actors in the 1950s. My childhood memories flooded back as I flipped the pages of the magazines. I recognized pictures of Tse Yin, Fung Bo Bo and Sek Kin, to name a few, who were in the prime of their careers at that time. Our conversation took place in different parts of her home, and transitioned from one collection to another, such as her mother’s Singer sewing machine that included accessories and a receipt dated 1936; her old Scholar’s game made from animal bones; her extensive collection of Chinese red packets; her collection of paper cranes she made, and her one and only porcelain model of the old C.K. Tang building. Jessie worked in C.K Tang since the day it opened for business till her retirement in 2008. With each collection, a new insight into the life of this incredible lady was revealed.

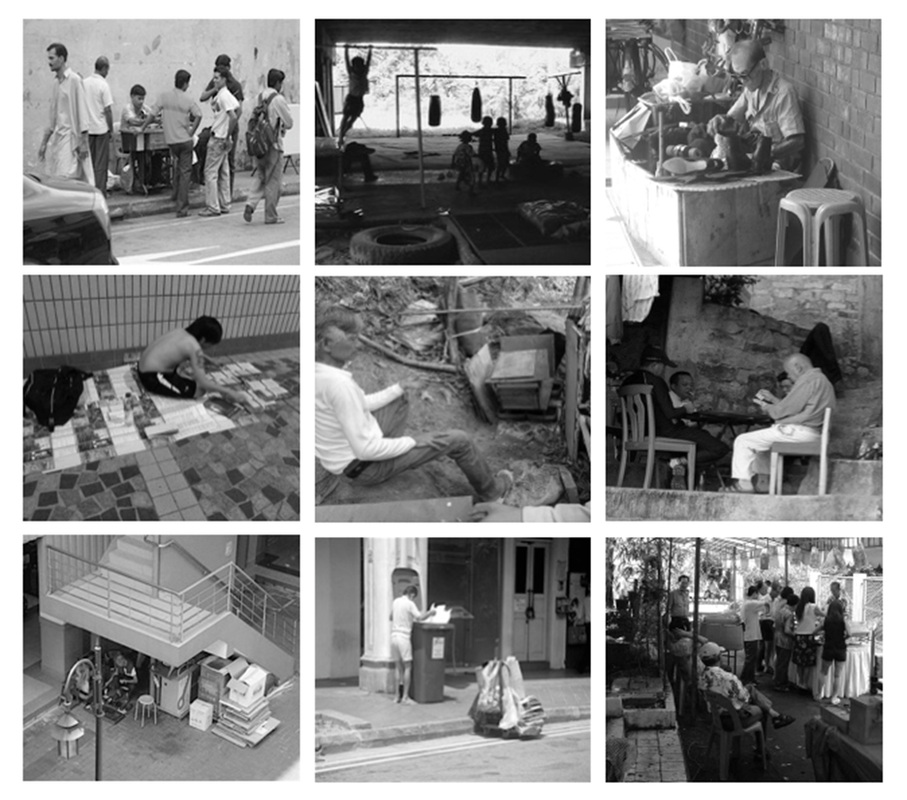

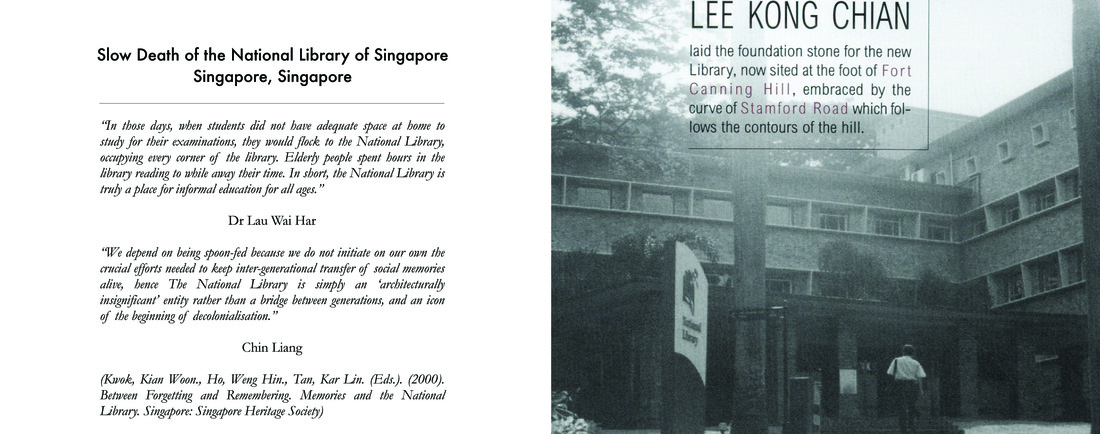

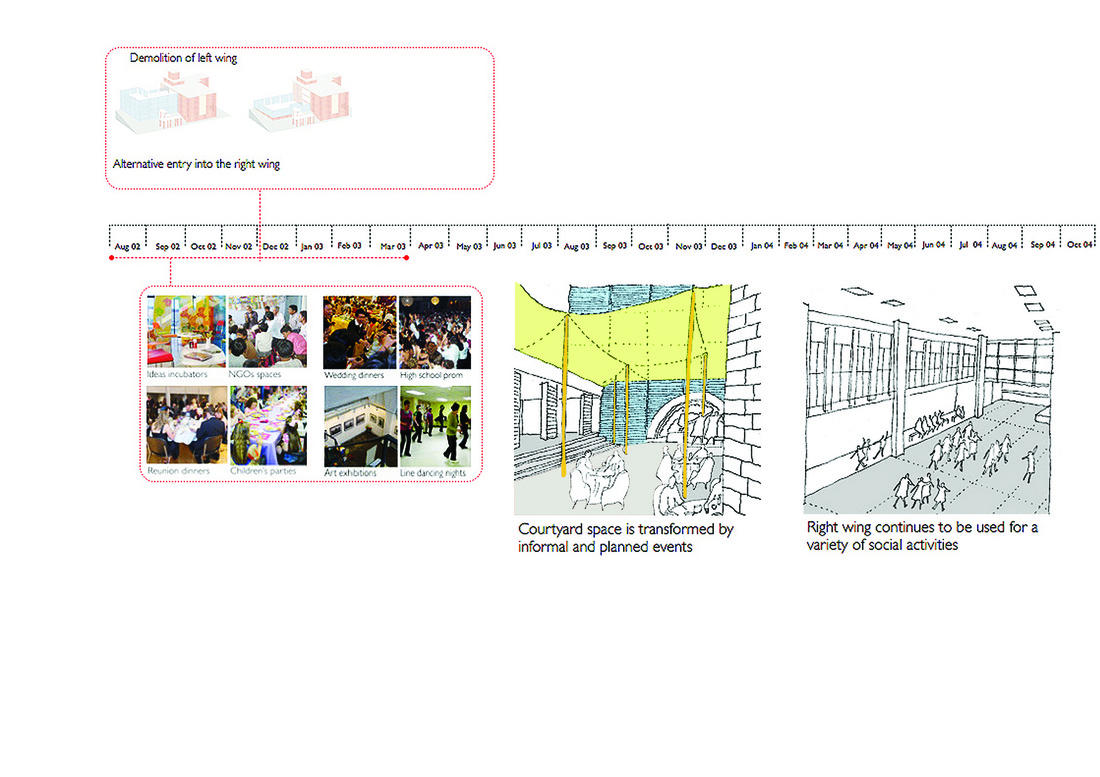

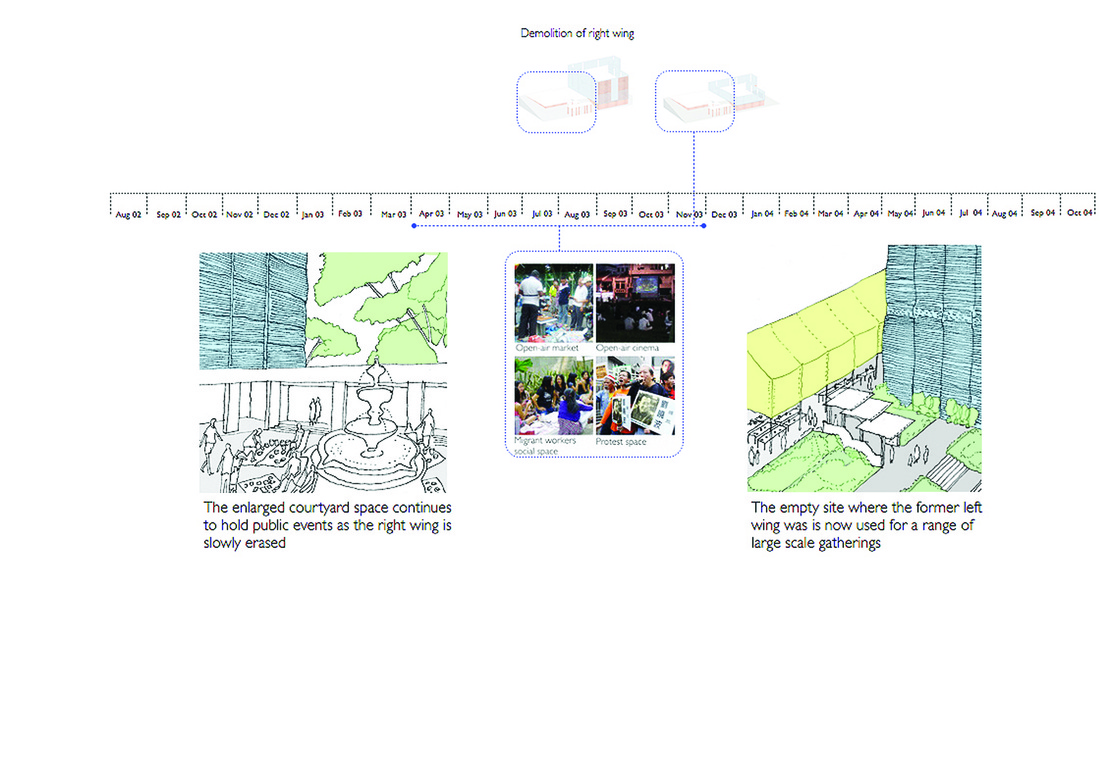

In the Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade avoided her death by telling an endless chain of folktales to King Shahryar each night. Her stories prevented the King from ordering her execution at the dawn of each day as he was mesmerized by the unbroken web of folktales. I felt the same when I was in Jessie’s flat- an intriguing and fascinating place where in the course of 30 years, it evolved into a Living Museum housing her rich and assorted collections. Her weaving of everyday life, memories, personal stories, histories and cherished objects left me enthralled and desiring for more. My recent work revolves around the term Lesser Urbanism. It is inspired by William Morris’s 1882 essay The Lesser Arts of Life. Lesser Urbanism curates, examines and presents aspects of urban life in high dense cities that are overlooked or ignored. Their presences are often negotiated, contested, and sustained along the margins of society. Although urban development is progressing at a relentless pace in Asia, I find there are still the vestiges of traditional rituals and local customs subsisting alongside and in quiet resistance against the process of globalization and gentrification. To disclose and celebrate these local cultures and alternative spatial practices where resourcefulness, creativity and sociability are called upon to overcome unfavorable situations and material scarcity is imperative in Asia, as more and more vernacular knowledge and places are erased and forgotten. My on-going research project on the Wah Fu informal public space in Hong Kong is one such effort. (http://www.studiochronotope.com/informal-religious-shrines-curating-community-assets-in-hong-kong-and-singapore.html). My interest in Lesser Urbanism transpires through a slow, deliberative journey reaching back to my early graduate work at Cranbrook, where I was concerned with the rules of forming and how elemental forms circumscribe space and propagates an emergent order through a bottom-up process of placement, aggregation, extension and configuration. In Lesser Urbanism, I am equally keen to articulate forms of individual and collective judgment and governance, both tacit and stated, as well as social conditions that give rise to, scale out and sustain localized spatial organizations. They herald a novel urban experience, alternative strategies of configuring spaces and make visible a vernacular poetics that are more representative of our contemporary splintered and tangled lives heightened by increasing contingency, scarcity and entropy. The project seized the opportunity to provide the public a chance to be involved in the active remembrance of this much loved building through a process of dynamic re-programming and unbuilding over a period of two years. The library was a long established institution in the country and slated for demolition in order to make way for an underground expressway despite several public pleas for its preservation. Instead of closing the library and leaving it vacant till the demolition date, a series of events and uses of this building were proposed, according to their scales and temporal natures within the 2-year period. The notion of preservation and collective memory in the city took on a different meaning, while the idea of providing a slow passing of this building was akin to how we hold a period of remembrance when a loved one or friend passed away.

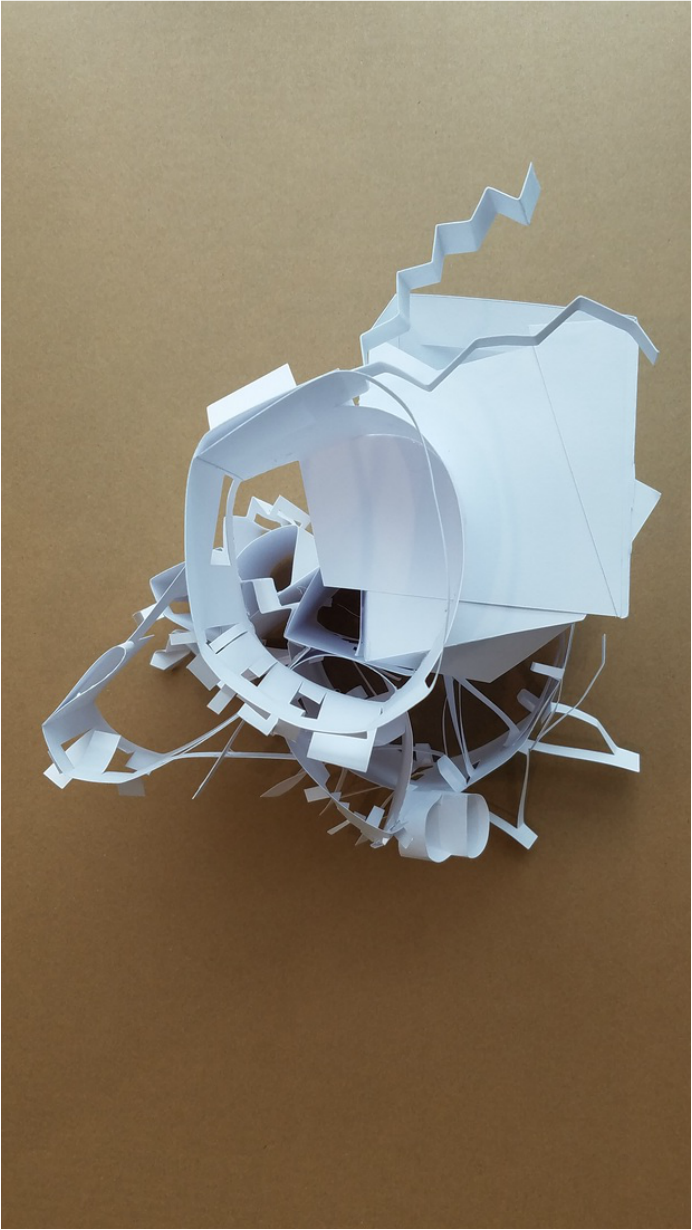

Rules, unlike laws have no ambiguity. They are not opened to interpretations. If you are ordered to leave the park at midnight, you have to. That’s the rule. If a ‘No Sleeping’ sign is displayed, it means just that. Clear and simple. You will be hauled out of the space if you sleep and no amount of negotiation or pleading will help. Sol Lewitt’s well known instructional drawings are a form of rule-based art. His instructions are there to direct how the work is to be executed. But what is fascinating for me is the fact that human error, poor workmanship, uneven surface and even misinterpretation can ruin the process of making the art even though the instructions are supposed to be clear. When I read some of the instructions casually, they were definitely not clear at all. I needed to devote all my attention to every single line of the instructions and read it several times to make sure that I understood. Perhaps the presence and threat of ambiguity are always lurking beneath the layers of rules. Sol Lewitt’s work is not unlike what an architect does when she writes a set of specifications for the construction of a building. The specifications spell out clearly the who, how, what and where of building the artifice. It is also a legal document in the event of any building defect that leads to litigation. My work at Cranbrook began with this fascination with rules. I wondered how many ways could I bend, twist, overturn or bundle rules? I was equally curious to see what happened when I devised a rule for forming and followed it to its logical conclusion? Would it be so predetermined that I would not be surprised by the outcome? Would the process disrupt my preconceived idea of what it would become? What if there was an element of eccentricity built into the rule, like a virus, so that the form would naturally deform along the way and caused it to deviate from its logical end?

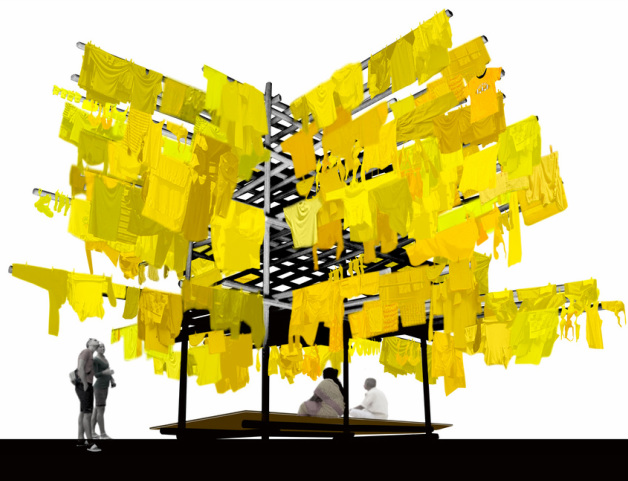

I grew up in a shophouse. The kitchen was at the end, three steps down. It had a tall ceiling and one side was opened to the outside. When it rained, the whole kitchen would get wet. My grandma had a blue tarpaulin made that she rolled down to stop the rain from coming in. One of things I remember most about the kitchen were the strings of orange peels hanging from the big exhaust hood above the stove. Once a while, she would take some of the dried ones down and used them to make green bean soup. We don’t do this anymore do we? Just eat and throw away now. The kitchen was my favorite place in the house. Before every dinner, she made sure the kitchen god was 'fed'. Nothing fancy. Just placing a fresh set of joss sticks in the urn. Before the rice dumpling festival. My mother, grandma and a few female cousins spent many days and nights in the kitchen making the Bak Zhangs. They cooked them in large metal drums of boiling water. There were three of them, spread out in the kitchen and sitting on top of kerosene stoves,. My mother and cousins would keep a watchful eye over the flames while they bundled the cooked Bak Zhangs into different plastic bags for our relatives and neighbors. Come to think of it now, it must be such hard work doing this. Somehow they just did it year after year because that was how it was supposed to be. It’s tradition. But it was not just work. The Bak Zhang team would talk and gossip into the night as they made the rice dumplings while I sat on the steps listening to their conversation- about in-laws, their children, husbands, work and other things grown-ups talked about. Looking back, I guess that’s how I would describe family to someone. Being together, doing things, talking. Nothing extraordinary really. Just everyday stuff. Now that there are just the three of us in Chicago, I feel my daughter is missing out on what I experienced living in an extended family surrounded by cousins, aunts and uncles. Even though I was the only child, I never felt alone. It was not all good all the time but it was comforting to know there was someone looking out for you besides your parents. My wife would disagree. She said since my daughter did not have the same experience, she would not feel that something was missing. It’ll be different for her here. Maybe she’s right. Chicago. Summer 2007 As a kid growing up in Singapore, my mother constantly reminded me to avoid walking below dripping laundry hung out to dry from the high-rise, government subsidized apartment blocks. Besides the possibility of getting wet, she believed it would bring bad luck to the person, especially if it came from wet undergarments. I did not dare to challenge her stern advice, for fear that she may be right- at least the bad luck part...

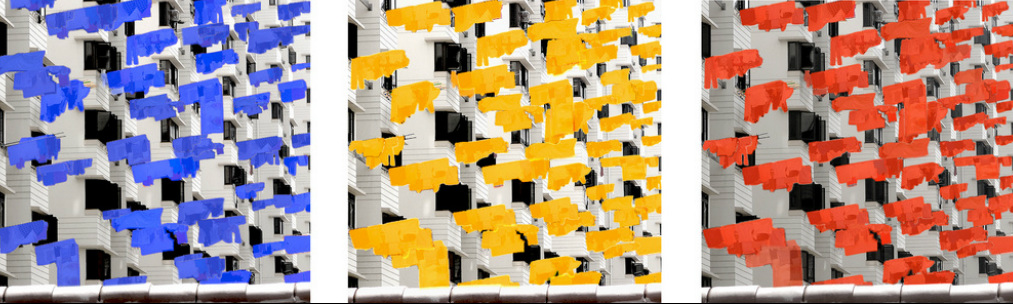

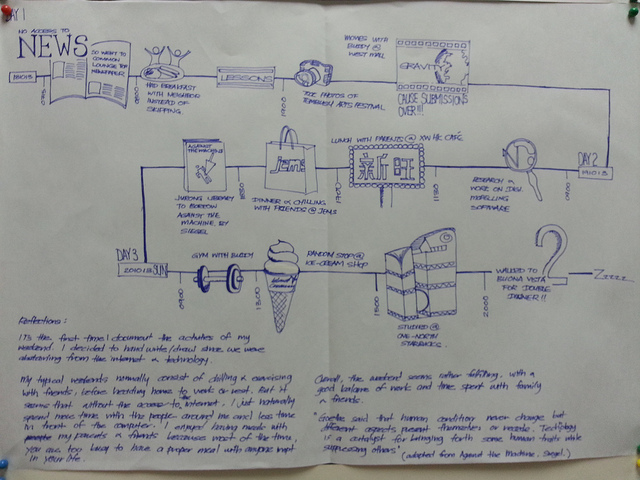

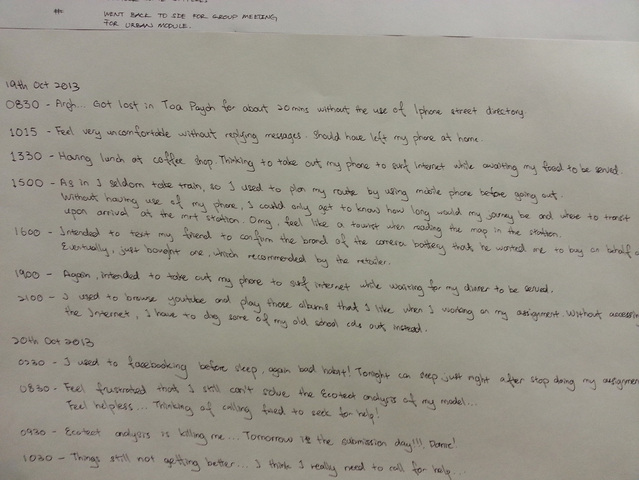

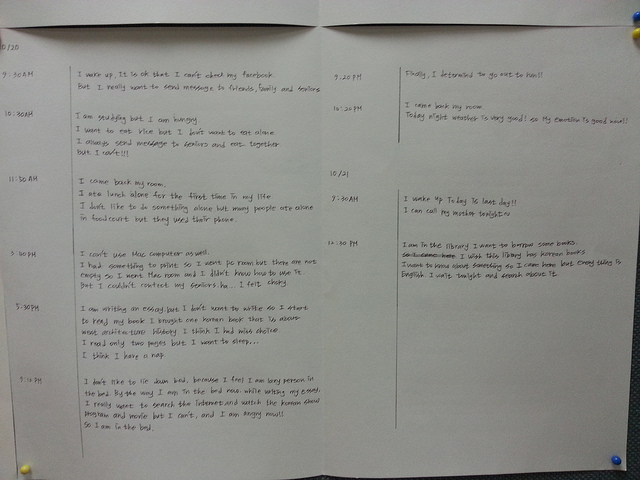

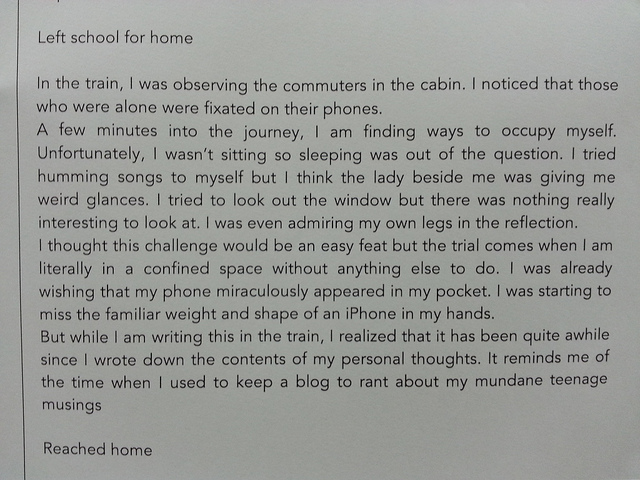

Laundry Art consists of two proposals for public installations that speak about the multi-layers of meaning, belief and the interplay between a simple, everyday practice in the city and the process of urbanization and modernization. One can see the correlation between how clothes are washed and dried, and the social transformation of the city-state through time from the history of laundry drying in Singapore. During the British colonial era, Indian laundrymen called Dhobis would collect, wash and dry the clothes in a vacant public space before sending them back to their customers. With the advent of the washing machine and the mass housing of urban dwellers in public high-rise apartments, clothes are washed indoors and dried using a simple technique of attaching wet laundry onto bamboo poles that are inserted into hollow steel pipes outside the apartment. The practice is mostly carried out nowadays by hired domestic workers from neighboring countries or replaced by laundry dryers. The domestic workers have to get used to this practice in a relatively short time as failure to do so may result in falling to one’s death. The heavy influx of new immigrants to the city-state the past few years also meant that newcomers need to be mindful of the implicit outdoor laundry drying etiquette if they were to avoid incurring the rage of local residents. Recently, architects designed the new high-rise apartments by cleverly shaping the building façade to hide this unique practice. It was deemed that wet laundry sticking out of government subsidized housing blocks is ugly, a nuisance, and potentially dangerous. Perhaps even a sign of backwardness? In a sense, what began as a practice, which took place outdoor and presented in full view of the public has been interiorized and gradually made invisible in Singapore as the city-state constructs with ambition, vigor and unsentimental pragmatism towards the future. Architecture students in Singapore were asked to avoid using their cellphones over one weekend and record their experiences. Below are some of their reflections.

An interesting feature of highly urbanised and Westernised Asian cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore is the occasional Chinese religious shrine lying next to a tree, in a discrete section of a public space or at a certain road junction. Some of them are erected by individuals or groups to express their gratitude for an answered prayer or to ensure a harmonious environment. Others begin when the altars of “house gods” or religious statues are “left behind”, because the previous owners have relocated to another home, or because the younger generation no longer observes the same religious practices after the passing of elder family members. To the older Chinese generation, religious statues formerly acquired for home collection and worship are not to be discarded disrespectfully. They are either given to another “caretaker” or are relocated to auspicious places, such as under a tree or beside a roadside rock.

|

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed