|

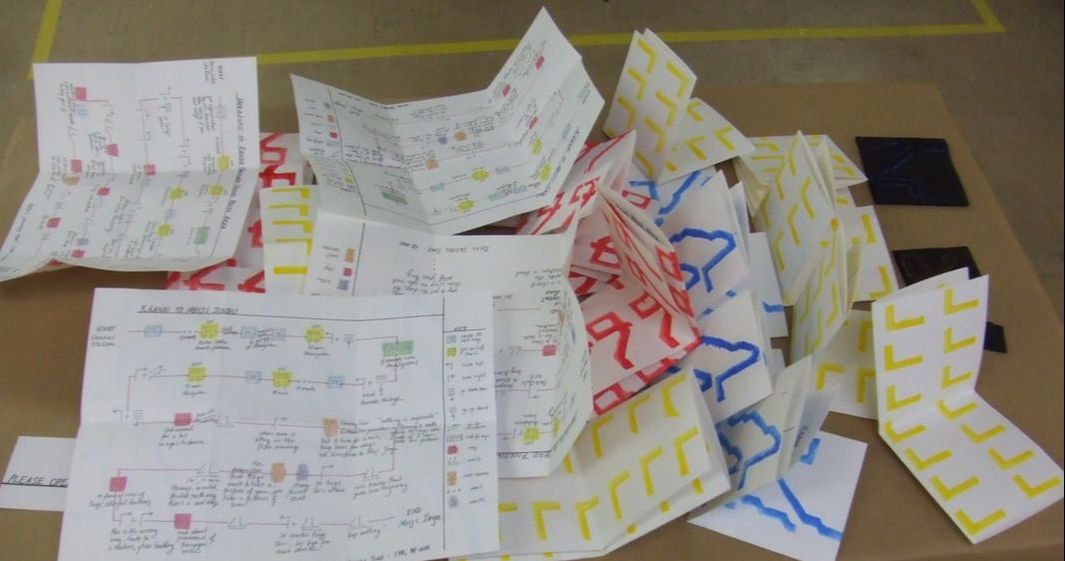

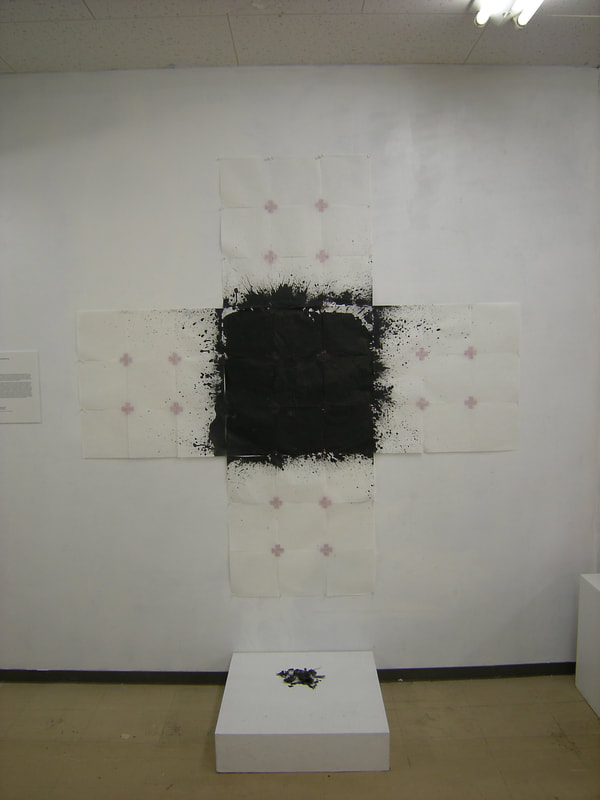

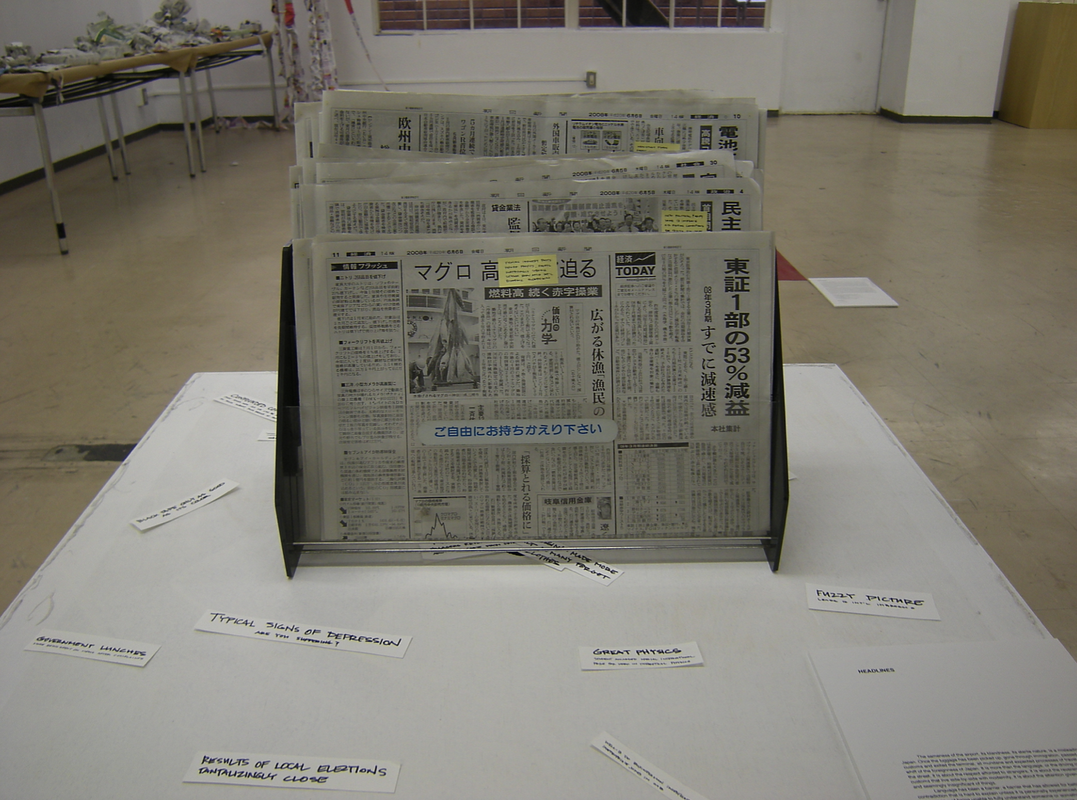

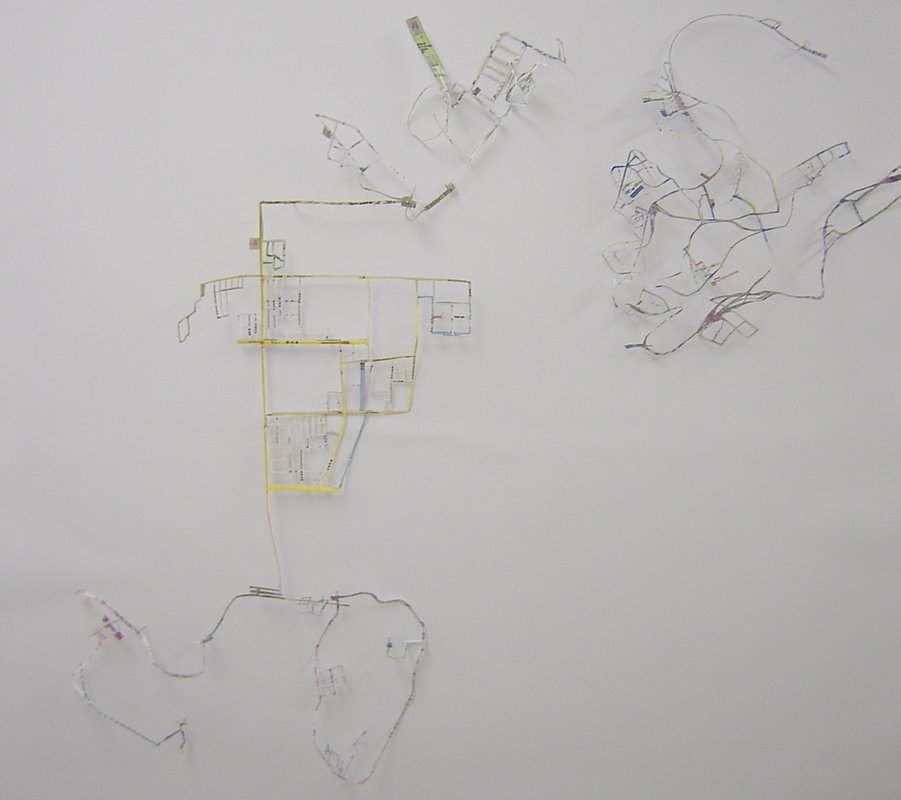

In his book The Empire of Signs, Roland Barthes offered one reality of Japanese society through his readings of an array of everyday objects, activities, places, body gestures and features as well as the arts. Edmund White, reviewing Barthes’s book in the New York Times Book Review wrote, “If Japan did not exist, Barthes would have had to invent it…” Similarly, in our everyday life we face a ubiquitous stream of stories, news, data and information disseminated through different media locally and globally. Whether we categorize them as facts, truths or rumors, their constellations around the globe continue to shape and reshape the reality we live in. As an architect, a designer and an artist, we are also shaping the world around us by amplifying, challenging and re-defining the given through different media and scales. The Bunka Oudan project begins with a few primary questions on Japan and will end with an exhibition of our personal maps. What is Japan? How do we know Japan? How do our preconceptions of Japan affect our on the ground experience? How do we depict our encounters and experiences in a map that is both personal and sharable? Thomas Kong. Associate Professor. AIADO Handkerchief Maps Almost from the moment I arrived in Japan, I have been fascinated by its train system, which is possibly one of the world’s most efficient and extensive, running the length of the country, from major metropolises to small villages. The station, at the center of this vast network, acts almost like a living, breathing organism, inhaling and exhaling people, filling up and emptying, every hour, every day. For the Japanese, these dense, frenzied transitions from station to station are a part of daily life, but as a tourist, unused to such intense, crowded movement, it made me very conscious of the way people negotiate and traverse space, and the signs that mark these processes. This kernel of a thought began to grow as I visited several Shinto shrines, most notably the Grand Shrine of Ise. In walking through a Shinto shrine, it is not just the main building that is the shrine, but the journey leading up to it – the experience of getting there is as important as the destination. If you speed up the ritual of the shrine, you arrive at the train station, at the city. In Tokyo, the heart of this vast intersecting system, once you emerge from the underground maze of platforms, shops, and human bodies, a different type of journey begins. Tokyo is a city without street names and numbers – you have to locate where you are and where you are going by other indicators – a storefront, a mailbox, a vending machine – or by asking people. Every place exists only in its relation to its surroundings. This work is a record of my own journeys through Tokyo. Each of the three separate trips (Kannai to Meiji-jingu, Harajuku to the Kanda second-hand books area, and Ochanomizu to the Ueno Zoological Gardens) are presented in the form of a handkerchief, a ubiquitous Japanese object that has intrigued me, becoming a personal, pocketable guide, a map of my unique experience. Namrata Krishna. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: No Address Namrata made a series of ‘handkerchief maps’ that were based on her identification of prominent street level landmarks, objects and activities she witnessed as she traversed the same routes everyday in Japan. Instead of a conventional street map consisting of abstract symbols, her maps recorded her visceral encounters with these places and served as her personal mnemonic devices. They became important points of orientation for her. The handkerchief maps were also much more convenient and could be kept close to the body when she traveled. Stuff Wrapped This project encompasses both the art of collecting and wrapping. The idea of creating something out of trash and found objects is important to me because I find it rather challenging to avoid consuming and spending. As I walked through Japan, I began collecting a series of objects that I found interesting as a way to log my experiences. The collection lasted for 12 days and is composed of both man-made and organic materials. I began collecting even though I was not sure what I would be doing with the stuff that I kept accumulating, but I knew I wanted to create a project of this collection as a way to map my time in Japan. The work displayed is my collection wrapped. No longer is the object important, but rather, it is about the wrapping of the object. The form of wrapping corresponds to the object itself and the number of times an object is wrapped corresponds to the day it was found. One may find themselves unwrapping something up to 12 times only to find something in the center that is very much unimportant or to find nothing in the center. As Roland Barthes mentions in Empire of Signs, one can spend a long period of time unwrapping. It creates a sense of excitement and wonderment as to what will be found underneath, but once the center is reached, the object is often insignificant. Nirvine Tawancy. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Packages Nirvine's method of wrapping took into consideration the forms of the empty containers and packages as well the days they became trash. These ‘wrapped stuff’ were given a second life later when they were offered to the visitors as gifts. Instead of a two dimensional map, Nirvine’s map was a daily physical record of her consumption patterns. It was a map not made to record for posterity as it gradually lost its overall body and disappeared into the circulation of stuff again when each piece was given away. Impact Investigation This project is a mapping investigation of an impact. The day trip to Hiroshima I made last week left me emotionally exhausted. However, over the days after my visit I began to think about a couple things. I was struck by the idea that the atomic bomb gave a center to the city. A large dot was burnt forever onto the map of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The staggering imagery of the aftermath showed the “perfect” plane that was created from the destruction. The city is now a thriving, pulsing metropolis. However, its identity will forever be connected to this mark on the map. These ideas compelled me to create this mapping project. Square shaped rice papers are attached with red tapes to form a larger square and placed inside a box, lining the interior. A light bulb filled with Sumi-e ink was then dropped from eye level into this box. After drying, the rice papers were removed from the box and pinned on the wall. A plan and four elevations recording the impact were ultimately produced. The + shape of the panels recalled the crosshairs used for targeting. The resulting pattern created from the ink was a reference to the maps charting the destruction of Hiroshima. The red crosses stitching the grid together called to mind haunting images of the thousands of victims being treated in the aftermath. The glass shards left in the paper recalled the pieces of glass that survivors had to lived with in their bodies for years after the explosion and continued to be removed from people even today. Gabriele Muracchioli. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: The Writing of Violence Interpreting the map as the creation and residual of a violent action, Gabriele’s work addressed the destructive impact and continuing horrors caused by the atomic bomb during the Second World War. Coincidently, when the work was flattened and presented on the wall as a map, it resembled both the crosshair of a target and how a kimono, a Japanese traditional dress is displayed in a museum. In this case, however, one that revealed an absent and violated body. Disorientation and Discovery Japan is a system that has been perfected, but is often opaque (and intriguing) to an outsider. My experience of Japan has been a constant attempt to decode this system – a desire to decode it because of its precision, deliberateness and beauty. Here, days have been filled with long journeys – often exhausting, confusing and frustrating – that are punctuated by moments of serenity, discovery and awe at the beauty and perfection of something experienced for the first time. These moments are when I feel closest to comprehending the intricate system that is Japan. Yet, the journey is as important as the destination in coming to know this country Audry Grill. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Center-City. Empty Center Combining her fascination and daily encounters with the Tokyo’s subway system, Audry created a map consisting of a network of colored lines in the ZAIM studio space that ran across floors, down the stairs and around the walls. The lines led to and highlighted objects that the students passed by everyday but overlooked during their stay in ZAIM. Some lines ended abruptly. The map echoed her experience of navigating through the labyrinthian spaces in the city that was filled with occasional annoyances but revealed unexpected discoveries as well. Greasy Japan Sweating has been a perpetually consistent aspect of my visit to Japan. For each day that I was traveling about, I would find time to blot my face with blotting papers purchased from the Muji counter of the local Family Mart. The shape and size of the grease stain left on the blotting paper changes in size as well as the quality of transparency- the outline defines the area of the stain left behind, tracing the amount of grease and sweat I produced at that time, day and location. Changes in humidity levels, increase in activity, the location’s climate, and time of day affect the differences of the shape and size left on the paper. Patterns from the first few days have gradually disappeared over the course of my stay- perhaps evaporating or absorbing into the paper leaving no trace of grease and sweat on the paper.Documenting this temporal aspect and change from one period to the next has become an important aspect for me, and my visit to Japan. Rebecca Midden. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: The Written Face Becky transformed the pieces of blotting papers she used throughout the trip into a map that recorded the patterns of grease stains on her face. She noticed that depending on the time of the day and night, and the activity she was engaged in, the size of the stains varied. The stains were carefully traced over with a pencil. One could read from each map the intensity of each activity during the trip and collectively, they presented a fascinating alternative map of her stay in Japan. However, it was also an ephemeral map where the tracings of her earlier sweat territories gradually disappeared as her stay in Japan continued. Headlines The sameness of the airport, its blandness, its sterile nature, is a misleading welcome to Japan. Once the luggage has been picked up, gone through immigration, passed through customs and exited the terminal, all mundane and expected processes of travel, do you get a whiff of the foreignness of Japan. It is more than the language, or the driving on the other side of the street. It is about the respect afforded to strangers, it is about the reverence of the old, of past customs that live side-by-side with modernity. It is about the attention given to the most minute and seemingly insignificant of things. Language has been a barrier; a barrier that has allowed for better understanding. It is a contradiction that is hard to explain unless it is personally experienced. This project is about that occurrence—of being unable to fully understand someone or something, of perception and assumption, of understanding on a level notwithstanding language Jaime Rovira. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: The Unknown Language Jamie’s mapped the lost in translations between pictures and the Japanese text in daily newspapers. Despite the saying that a picture speaks a thousand words, it does not mean an accurate correspondence between a picture and its text in his case. Using a combination of yellow Post-It notes and strips of paper, Jamie attempted to ‘read’ the images accompanying the local headlines of the newspaper at the hotel every morning. During the exhibition, he also encouraged the visitors who do not speak the language to try and interpret the pictures in the newspapers. The process often led to very different outcomes, ranging from the absurd to the hilarious. Untitled This project maps an impression of my experiences in Japan by recording the everyday; the persistent shift between awkward and peaceful feelings. How our consumption and understanding of copious travel maps differ from our experience of a place, and how we process this information into memory. My interest in the rituals at the shrines and the collection of advertisement magazines led me to create these strips as a release of these impressions and feelings. Kirsten Hanson. Master of Architecture(2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Animate/Inanimate Taking the promotional magazines and pamphlets given freely along the streets, Kirsten folded them into the shape of a wishing tree and suspended it from the ceiling. Visitors to the exhibition could add their own wishes by attaching them to the tree. Whether wishing for good health, world peace or a new car, the tree accepted them without any discrimination. When a visitor added a wish, the movement of the body created a slight breeze that momentarily animated the wishing tree, as if it acknowledged the receipt of the wish. Map To journey through Japan is to walk paths that are less than linear. This project is about mapping this journey, limiting Japan to what I have witnessed and traversed. Maya Janczykowska. Master of Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: No Address Maya’s map fused her experience of vulnerability being in a foreign country without any knowledge of the language and customs as well as her difficulty in locating places while navigating the streets in Japan. This persistent experience brought into focus her memory of the streets more than the actual places she was supposed to find. Her maps were made by carefully cutting out the places visited, leaving only the lines of streets visible. In the chapter No Address, Barthes offered a different reading of how we orientate in a city; not by maps but through our bodies and memories. In the Middle Delicate. Fragile Enveloping. Folding, Surrounding. Weaving old and new Completing your soul. Fulfilling sense of peace and Overwhelming notions of grace. Extreme oppositions And soft light compose, Symphonies of unattainable qualities. What is real? Messy realities of history, past Through the soft light comes A progressive future. Confrontation with present violence Stirring overwhelming sense of peace We are those exact opposites Surreal moments that permeate Miserable vitality Spiritual depression Where is the boundary? Somewhere in the middle We meet. The black and white mix, Creating pages of text… That line our souls with: Ambiguity. Annie Kasper. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Millions of Bodies Annie’s map of Japan consisted of folded rice paper that twirled itself across the walls of the ZIAM studio. The map was made by repeating the same folding pattern over a specific period of time. Although similar in form, each piece became slightly deformed as the overall form negotiated across the walls. The map marked a moment of her stay in Japan and also alluded to the Japanese aesthetic of lightness and ephemerality, which Barthes described as running ‘from difference to difference, arranged in the great syntagm of bodies.’ ((((((((( ))))))))))) As travelers we scavenge (((((((((( ))))))))))). Memory is both fantasy and reality. We consciously seek and we unconsciously surrender. The intention of Haiku is revealed in essence while the structure is released. The project attempts to map the evidence of (((((((( ))))))))))). Brandon Styza. Master of Architecture (2009) Kimberly Richter. Master of Architecture with Emphasis in Interior Architecture (2009) Empire of Signs chapter: Without Words Kimberly’s and Brandon’s collaborative map-making project was a multi-media map of Japan. Brandon brought along with him to Japan his headphone and microphone which he meticulously recorded a series of everyday sounds throughout the trip. Sometimes he would wander away from the group or was left behind because he was so captured by the soundscapes around him. Both students later resampled them into a soundtrack that accompanied the moving images. The frenzied combination of images and sounds presented a rich and layered map-in-motion of their experiences in Japan. The Interstice Japan has been a study in contrasts- contrasts that are not clearly defined but blur, shift, transform and transport. It has shifted my thoughts as I consider the relative static-ness of my own culture. This project questions the line or the lack thereof between the sacred and the mundane. It explores the idea of sacredness as transitory- as not attached to place but rather to the process of moving through space. It is about intentionality rather than being in a particular place in time. From the ever-shifting shrines at Ise, to the temple thresholds stepped over at Nara, to the blurred separation between the floating Torri and its own reflection at Miyajima, this idea and feeling of temporality is all at once off-putting, appropriate and beautiful. Where does sacred space begins, ends, overlaps with the mundane? Do they lie in contrast or exist together in what Roland Barthes refers to as the interstice- to being “without specific edges” that is nowhere and everywhere. Sarah di Nicola Tranum. Master of Design in Designed Objects (2009 Empire of Signs chapter: The Interstice

Intrigued by the interweaving of the secular everyday life with the scared, Sarah Tranum made three light sources and placed them the floor. They were accompanied by a porcelain dish, a chalk stick and a note set on top of a simple wooden box. The note asked the visitors to draw a line demarcating the boundary between light and darkness around each light source. Using the metaphor of light and enlightenment and the circuitous body of lines, Sarah’s work revealed the visitors’ shifting, ambiguous and individualized boundaries between the spiritual and the secular. During the first day of the facilitation session in To Kwa Wan, I introduced the Circle of Gift Giving to the group. Sitting in a circle, each participant gave a small present to the person seating next to him or her. The ritual required the gift giver to share the source and meaning of the gift to the receiver. As the circle of gift giving enfolded, we shared funny, down to earth and poignant stories behind each gift. One participant forgot to bring a gift and she bought one in To Kwa Wan. Being practical minded, she bought a bottle of WD 40 from a car repair workshop as a gift and hoped it would be useful for the gift receiver. Another female participant gave a movie ticket to the participant next to her. She explained that it was from a movie date but her partner failed to turn up. She ended up leaving the movie theatre holding the unused ticket. A participant gave a small coin, which came from a memorable trip to Taiwan she made with her father, while another gave an old high school exercise book. She shared that the book brought back memories of her school days in Hong Kong after being away for many years.

The participants had to learn from the sociocultural and economic life of To Kwa Wan residents, and come up with interesting ideas to archive the fast disappearing neighborhood over a one-month period. They came from all walks of life and were strangers to each other. Before diving deep into the task, I felt it was important to first form a community of learners through the ritual of gift giving. As Lewis Hyde in The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World so eloquently wrote, "...it is not when part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when part of the self is given away, that community appears.” I was invited by the Make a Difference School in Hong Kong to be a guest facilitator for their 1- month in-situ studio in To Kwa Wan. Over 3 days in August, I gave a public lecture on the concept of Social Archiving and conducted discussions with the participants and local residents on the future of the neighborhood that was slated for re-development. Looking at To Kwa Wan superficially, one sees only the large number of car repair workshops, and would not have imagined a rich and diverse collection of social relations and history. Through my street conversations with the locals, I discovered a resident who played the flute to entertain passerby and gave a very good impression of singing birds. There was a pastry shop that have used the same 40-year old recipe since the day it opened for business, and even a car repair workshop that doubled up as a daycare for the child of a single parent who had to work part-time.

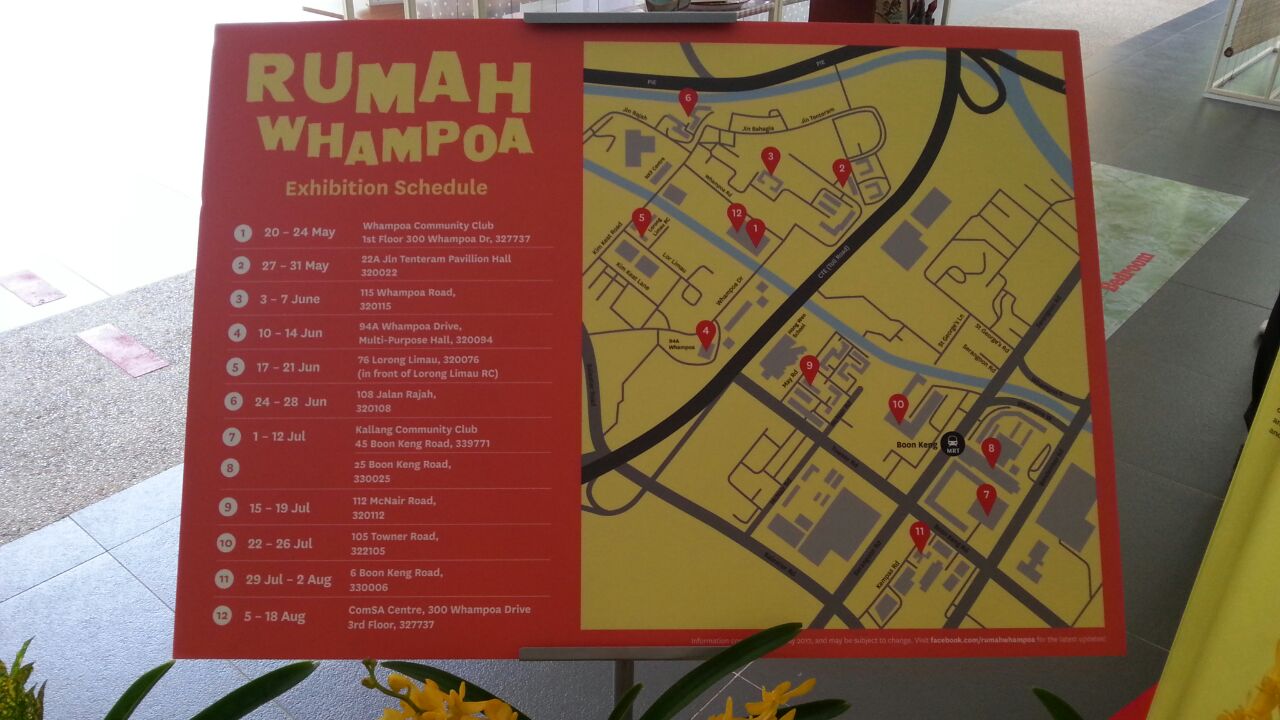

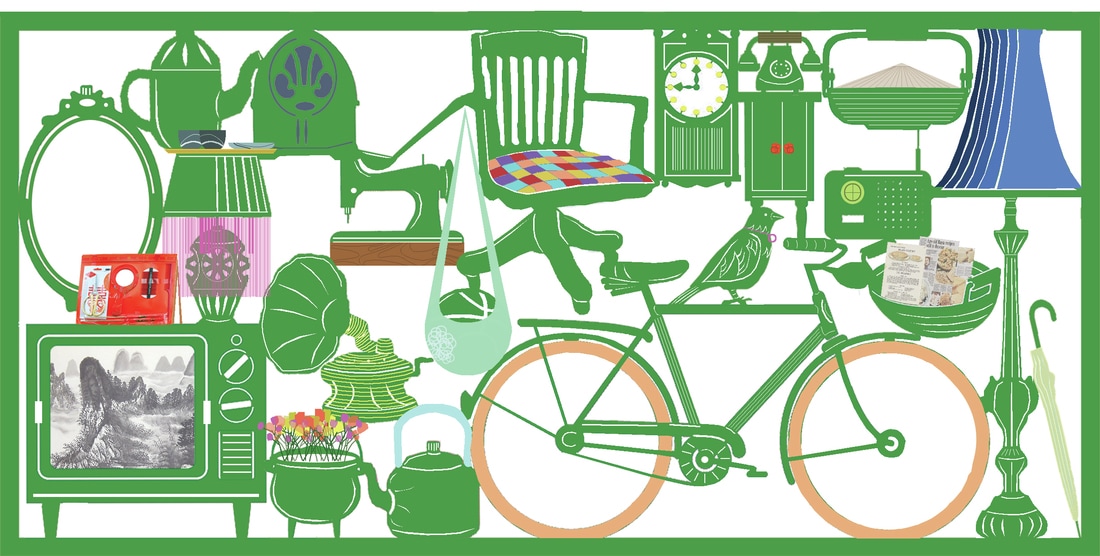

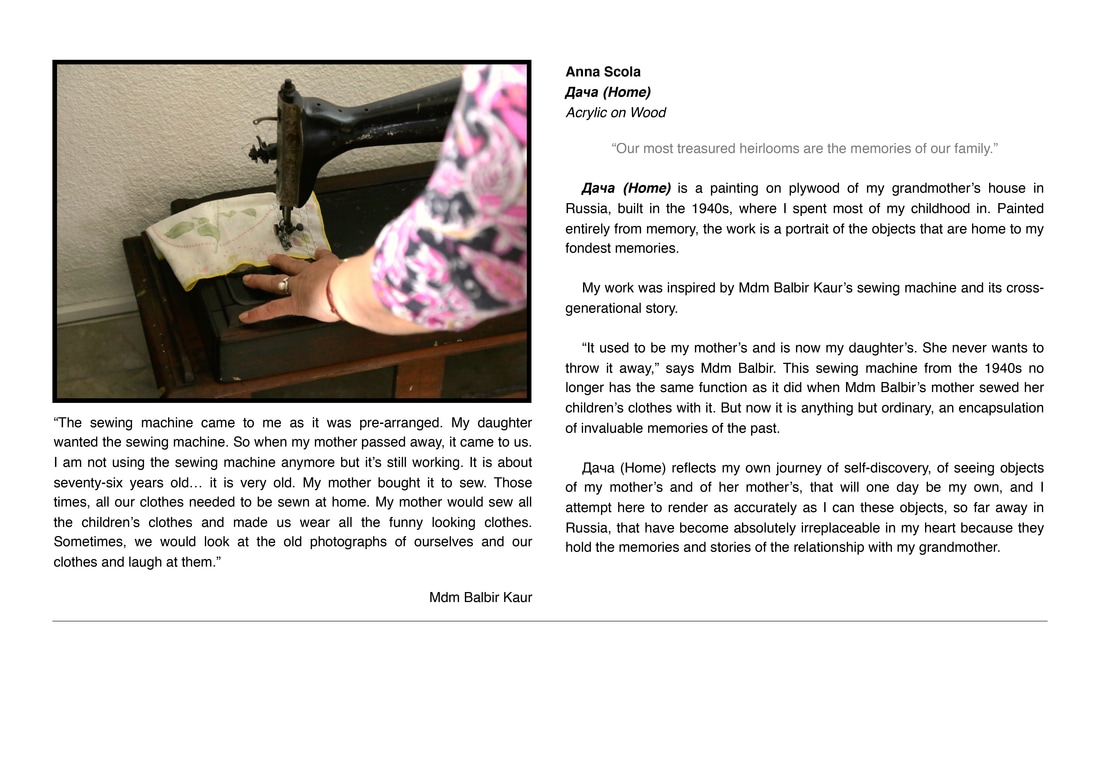

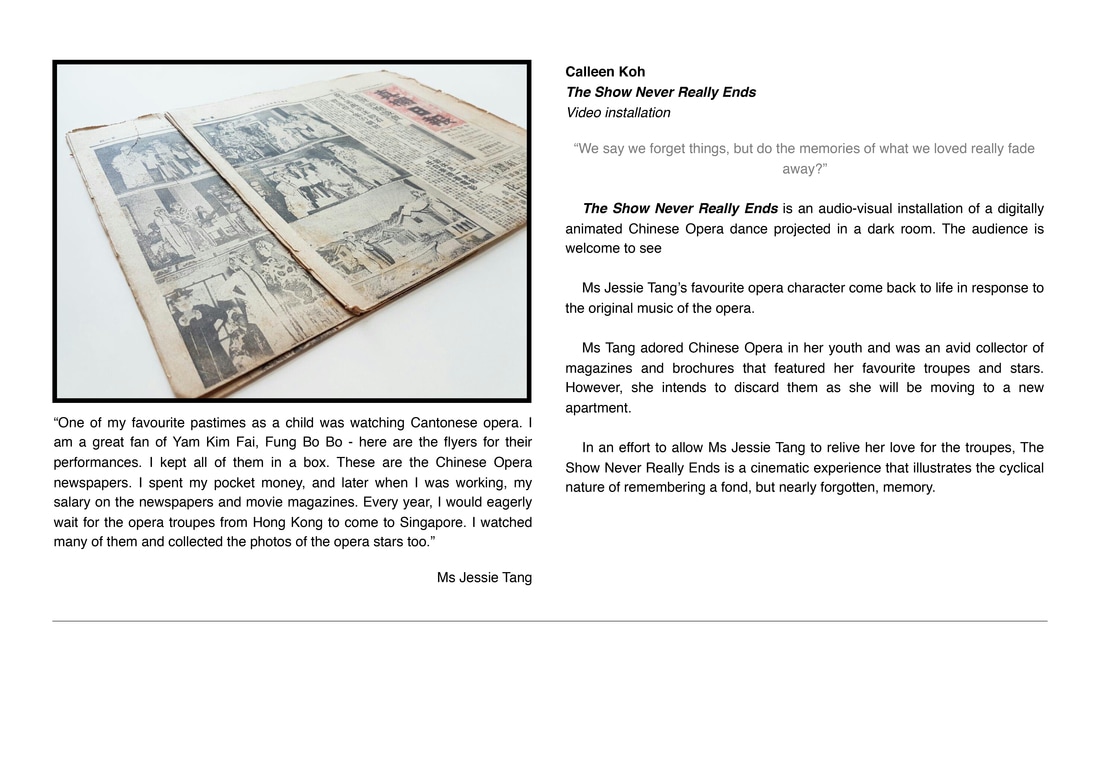

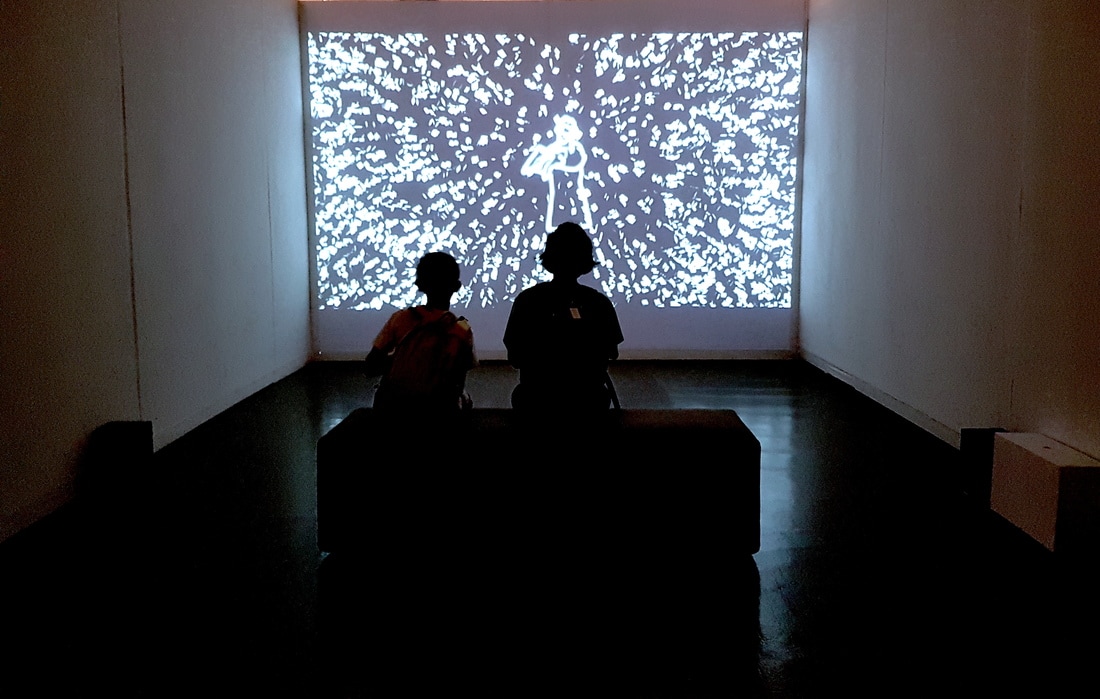

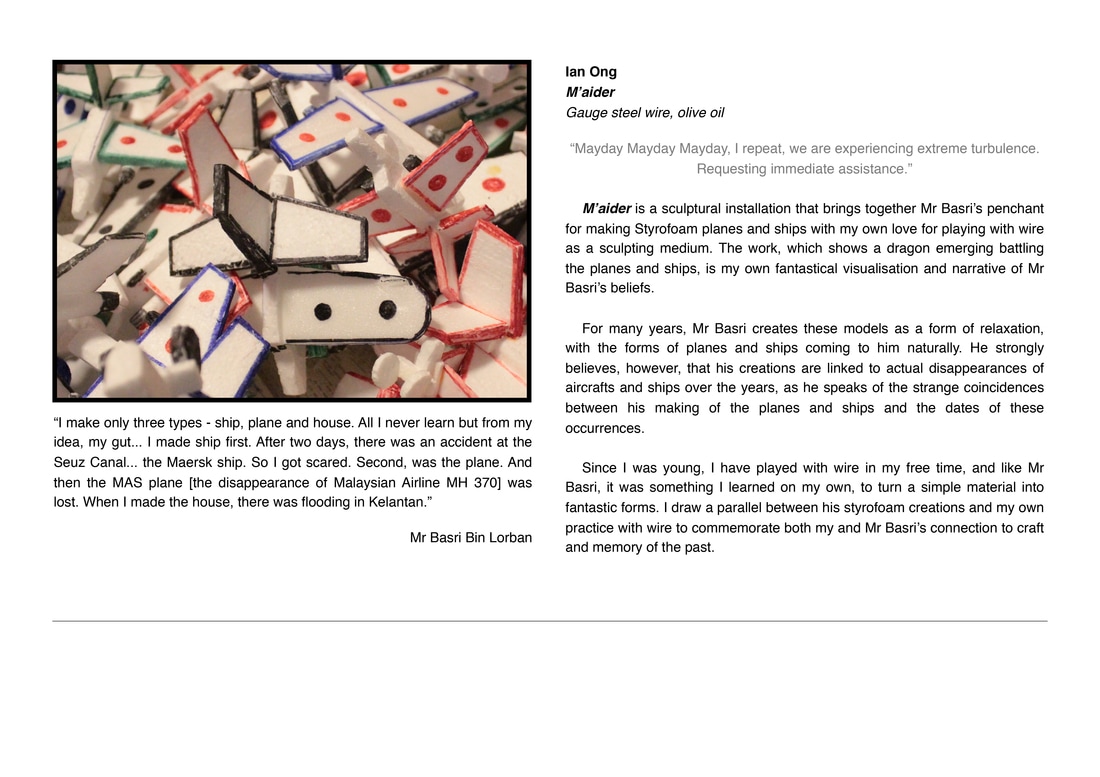

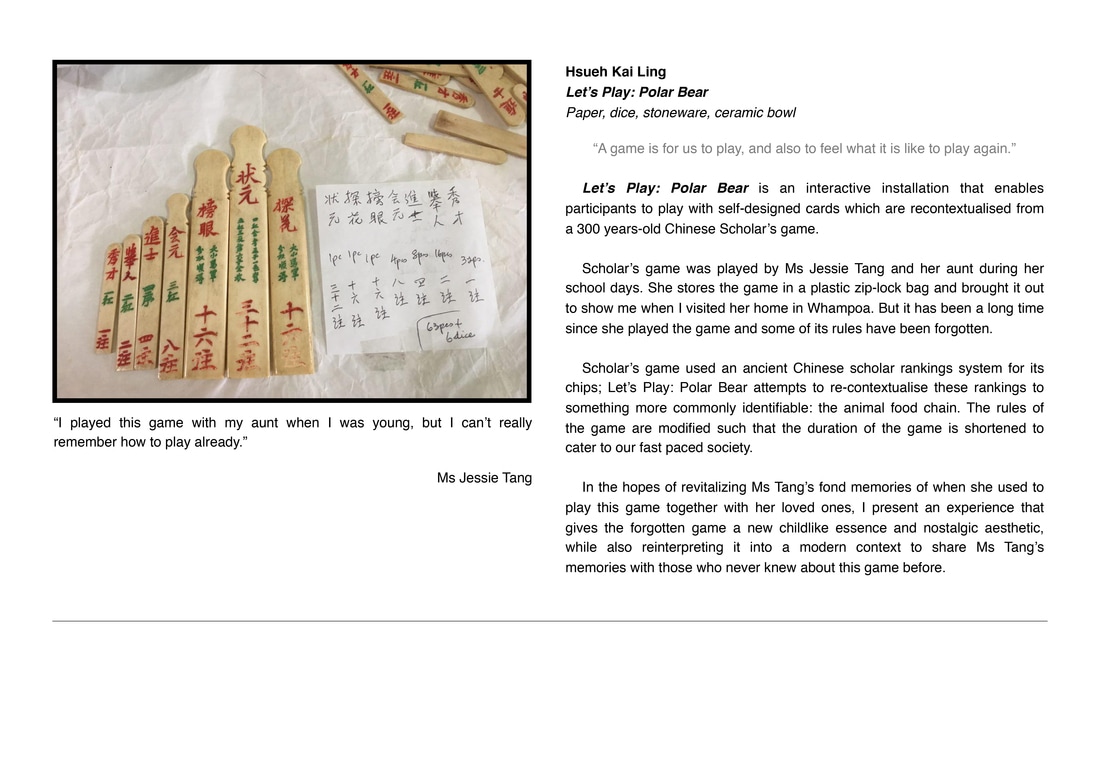

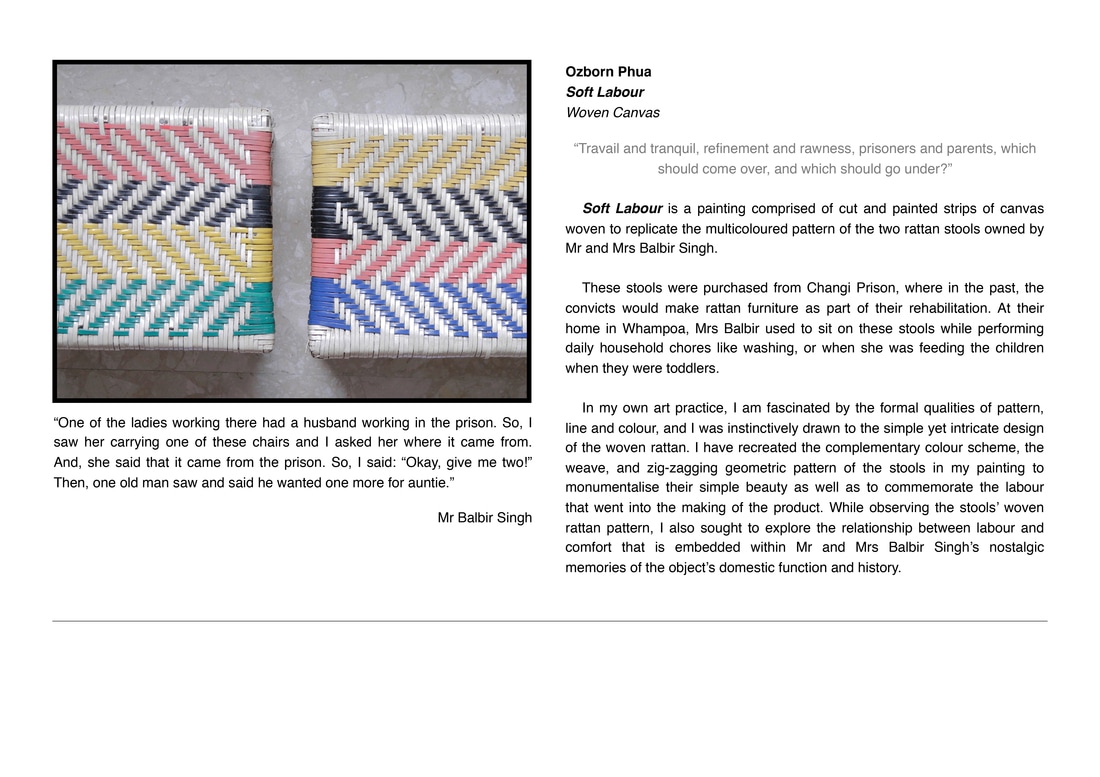

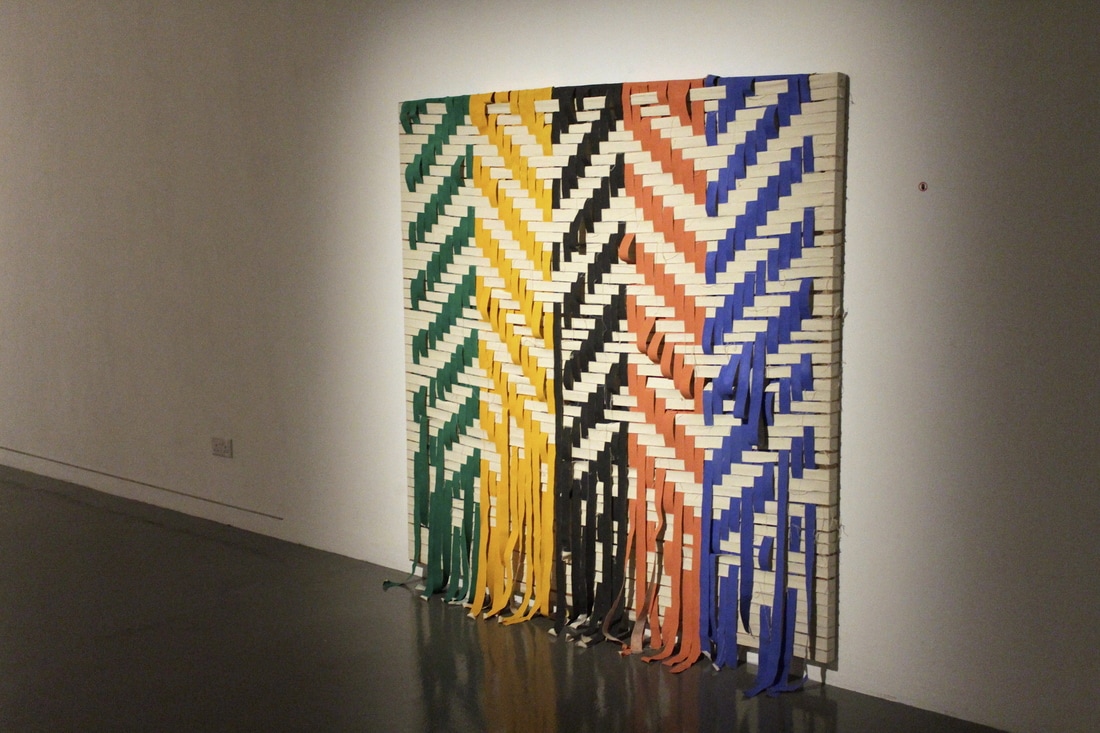

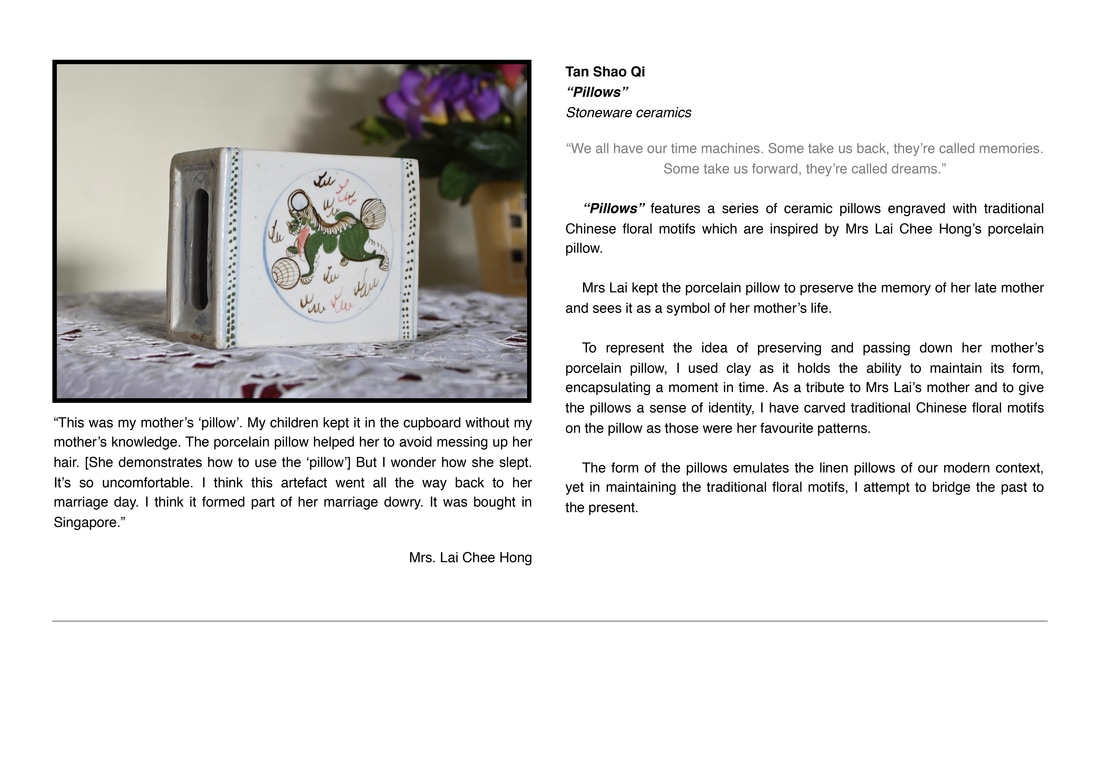

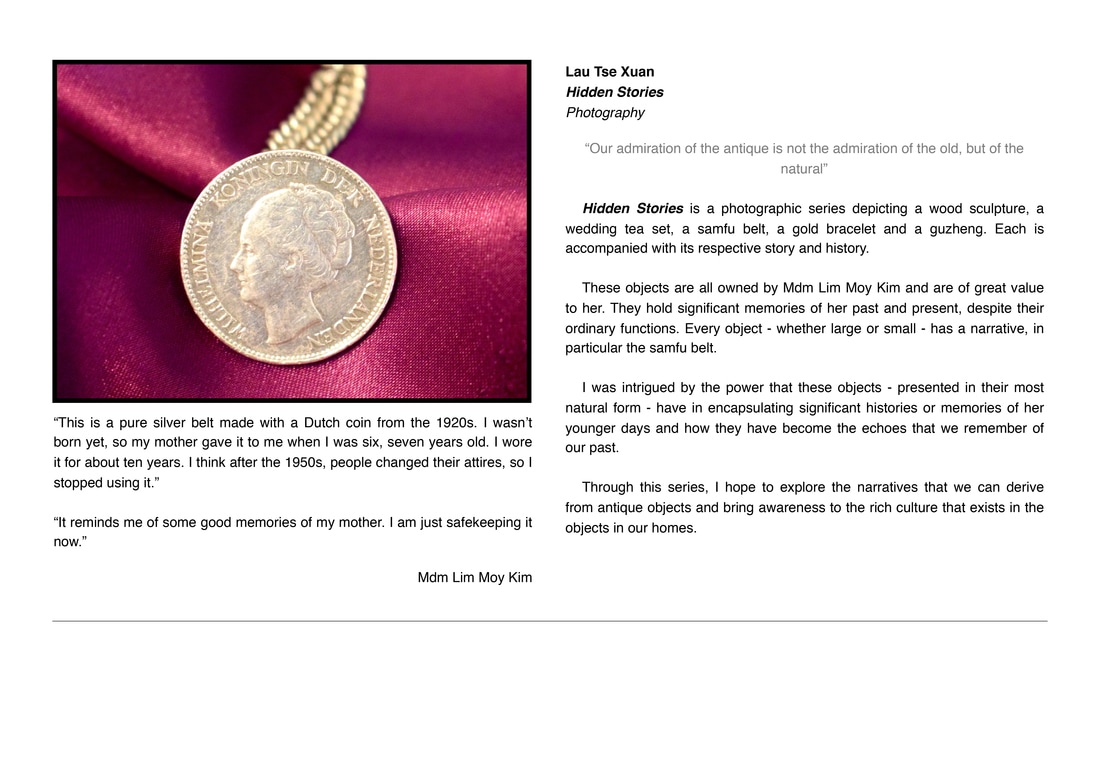

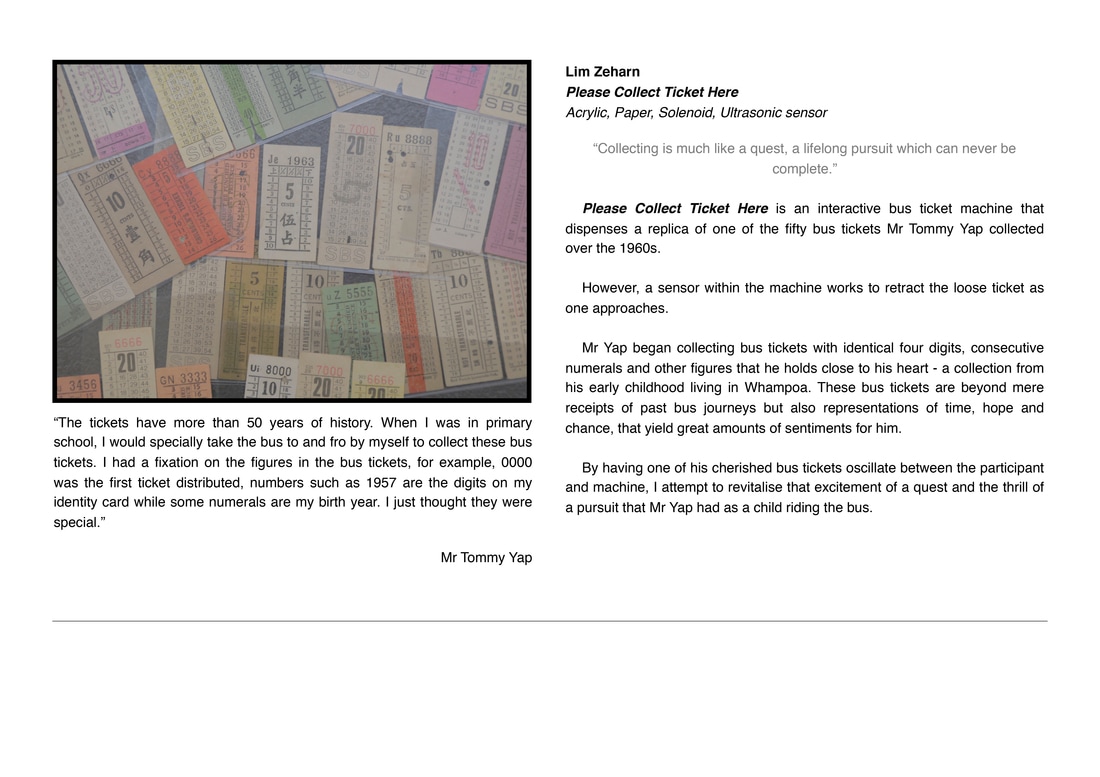

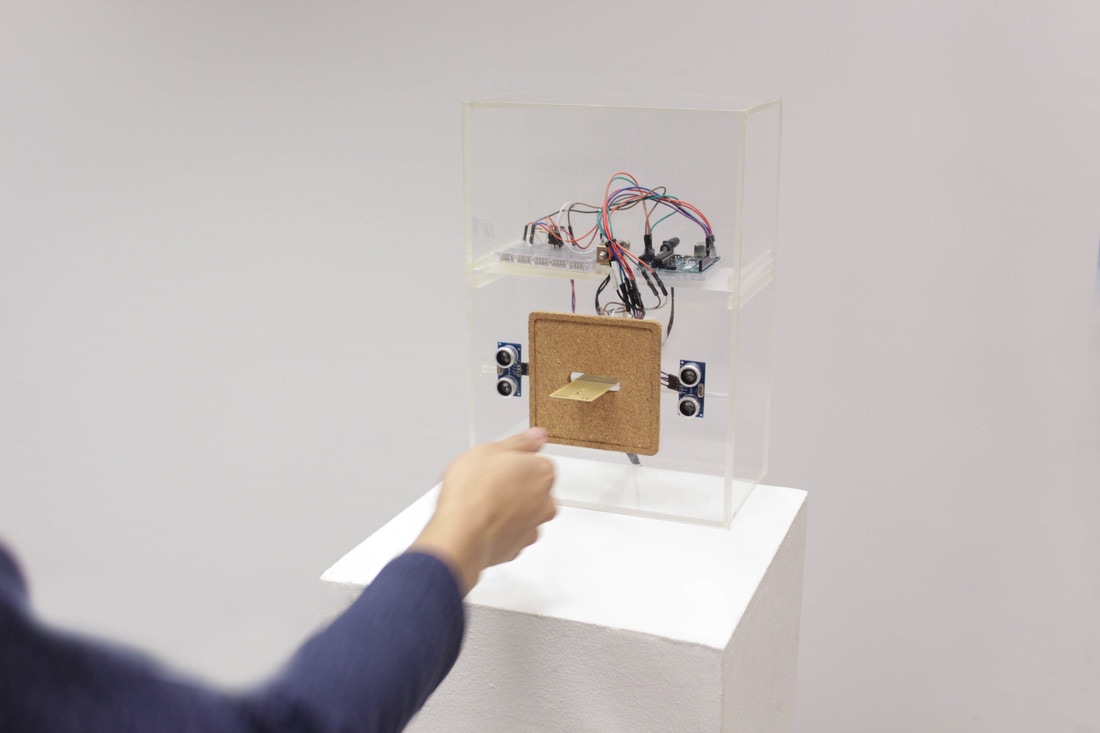

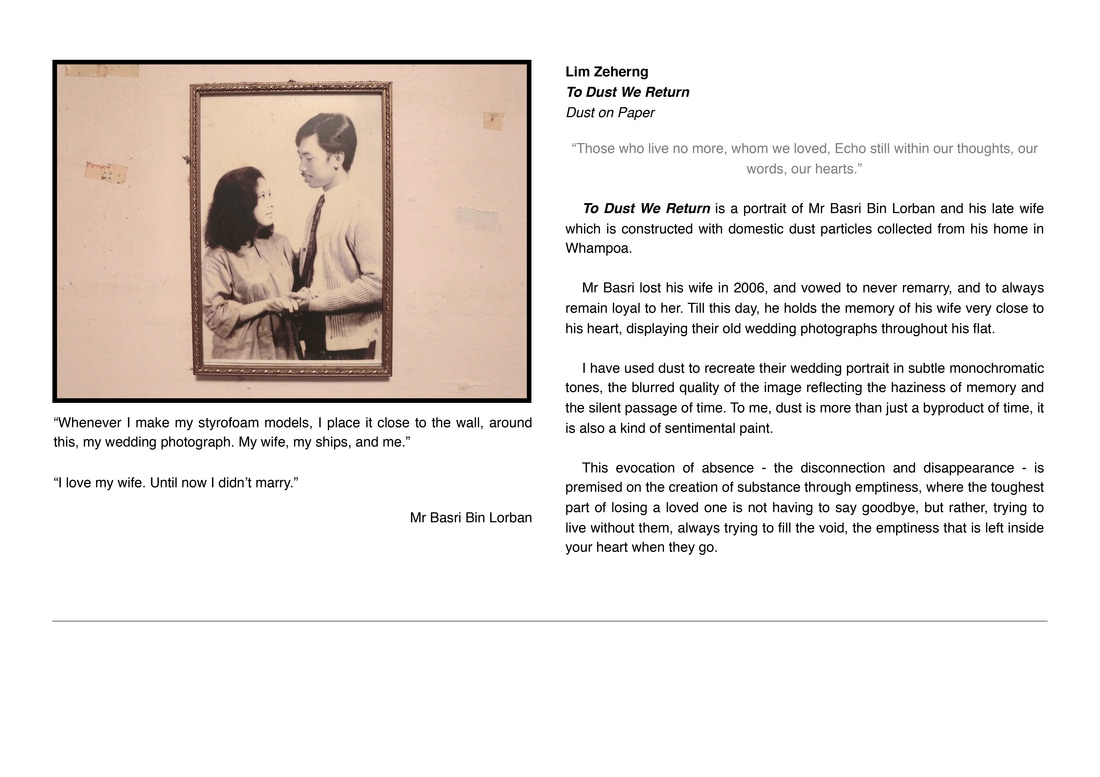

Rumah Whampoa presents two community engagement projects--Tangible Stories & Photo Voice—which the Whampoa senior residents participated in over the last six months. Conceptualized by various art collaborators residing locally and overseas, Rumah Whampoa exhibits a collection of verbal and visual narratives about the lives in Whampoa, as told by its senior residents. In Tangible Stories, the residents shared their personal stories of objects that had stayed with them over the years, and which they have kept as they moved into Whampoa. In Photo Voice, the residents learnt digital photography and in turn, presented their view of Whampoa through the photographic lens. Curatorial Concept The exhibition focuses on the idea of welcoming others into the lives of these senior residents. Styled with materials that harkens the past and using the concept of a rumah (home), the narratives are clustered by the areas that define activities in the home: outdoor play area, cooking/eating area, bedroom/study, etc. At each of these areas, the verbal and visual narratives captured through the two projects intermingle. The exhibition operates at two levels, presenting snapshots and anecdotal accounts as well as inviting the audience to be curious and to pick up some of these objects, further discovering some of the personal histories associated with them. Designed to be portable, these modular clusters are reconfigured at each new site which hosts the exhibition. In that way, a new variant and interpretation of “Home Whampoa” is created each time. Text by Jacelyn Kee. Exhibition design by Fellow. http://www.wearefellow.co/

Tangible Companions is a project to develop contemporary companions for a number of old artifacts that Whampoa residents have fond memories of. From January to April 2017, high school students will draw from the interviews and images curated from the Tangible Stories project to develop their proposals. By describing the outcome as a companion, the project aims to encourage a multi-scalar and an interdisciplinary inquiry grounded on an empathic creative response to the artifact’s history, qualities as well as its affective relationship with the owner. The project is conceived by Thomas Kong and led by faculty members David Gan and Vincent Leow from the Department of Visual Arts at the School of the Arts, Singapore (SOTA). Exhibition of Completed Works at The School of the Arts. Singapore. All photos courtesy of SOTA. “Art and Design should not only be an object but an excuse for a dialogue.” Douglas Gordon and Thomas Kong

“When a person or a building disappears, everything becomes impregnated with that person's or building’s presence. Every single object as well as every space becomes a reminder of absence, as if absence were more important than presence.” Doris Salcedo and Thomas Kong “In art and design, everything is particular. The more particular and the more intimate you get, the more you can give in the piece.” Doris Salcedo and Thomas Kong “I'm often asked the same question: What in your work comes from your own culture? As if I have a recipe and I can actually isolate the Arab or Asian ingredient, the woman or man ingredient, the Palestinian or Singaporean ingredient. People often expect tidy definitions of otherness, as if identity is something fixed and easily definable.” Mona Hatoum and Thomas Kong “Every day, we came to [the exhibition space] to work together. We continued to organise these things and spaces. So actually, this exhibition is not about displaying, but about organizing spaces. Song Dong and Thomas Kong “The process of living and the process of thinking and perceiving the world happen in everyday life. I’ve found that sometimes the studio is an isolated place, an artificial place like a bubble – a bubble in which the artist and designer is by himself or herself, thinking about himself or herself. It becomes too grand a space. What happens when you don’t have a studio is that you have to be confronted with reality all the time.” Gabriel Orozco and Thomas Kong “I always want to design a frame or a building or structure that can be open to everybody.” Ai Weiwei and Thomas Kong “Designing and Architecture is not a profession, it is an attitude.” László Moholy-Nagy and Thomas Kong “An artist and a designer must constantly be faced with new and always different problems.” Cai Guo Qiang and Thomas Kong “Many artists and architects try to construct a world for themselves: from concept to format. From knowledge to inspiration, from a methodology to learn about, and to express the world.” Cai Guo Qiang and Thomas Kong “Caress the detail, the divine design detail.” Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong “Artists and designers themselves are not confined, but their output is.” Robert Smithson and Thomas Kong “Here is what we have to offer you in its most elaborate form in graduate advising -- confusion guided by a clear sense of purpose.” Gordon Matta Clark and Thomas Kong “A novelist and an architect are, like all mortals, more fully at home on the surface of the present than in the ooze of the past.” Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong Life or a building is a great sunrise. I do not see why death and unbuilding should not be an even greater one. Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong The pages and spaces are still blank, but there is a miraculous feeling of the words and lives being there, written in invisible ink and clamoring to become visible. Vladimir Nabokov and Thomas Kong It ought to make us feel ashamed when we talk like we know what we’re talking about when we talk about love and design. Raymond Carver and Thomas Kong You’ve got to work with your mistakes and intuitions until they look intended. Understand? Raymond Carver and Thomas Kong If you only read the design books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong I dream and design. Sometimes I think that’s the only right thing to do. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong Death or unbuilding is not the opposite of life or building, but a part of it. Haruki Murakami and Thomas Kong One must not, however, imagine the realm of culture as some sort of spatial whole, having boundaries, but also internal territory. The realm of culture has no internal territory. It is entirely distributed along the boundaries, boundaries passes everywhere, through its every aspect...Every cultural act lies essentially along its boundaries.

Mikhail Bakhtin. The Creation of Prosaics The city is filled with people engaged in a wide variety of daily activities every morning- going to work, buying breakfast along the way, delivering goods and services, cleaning the shop front, waiting for the bus, etc. These activities occur repeatedly each day without fail, to the point of being involuntary like breathing. But their repetitions also instilled a sense of dullness and monotony. What happens when we reframe these ordinary activities as various forms art, ranging from public sculptures to performances? Will we begin to see and value them differently? Taken from Hong Kong one morning, the various objects and human activities reveal the rhythm and relationship of space, objects and people in the fast- moving city.

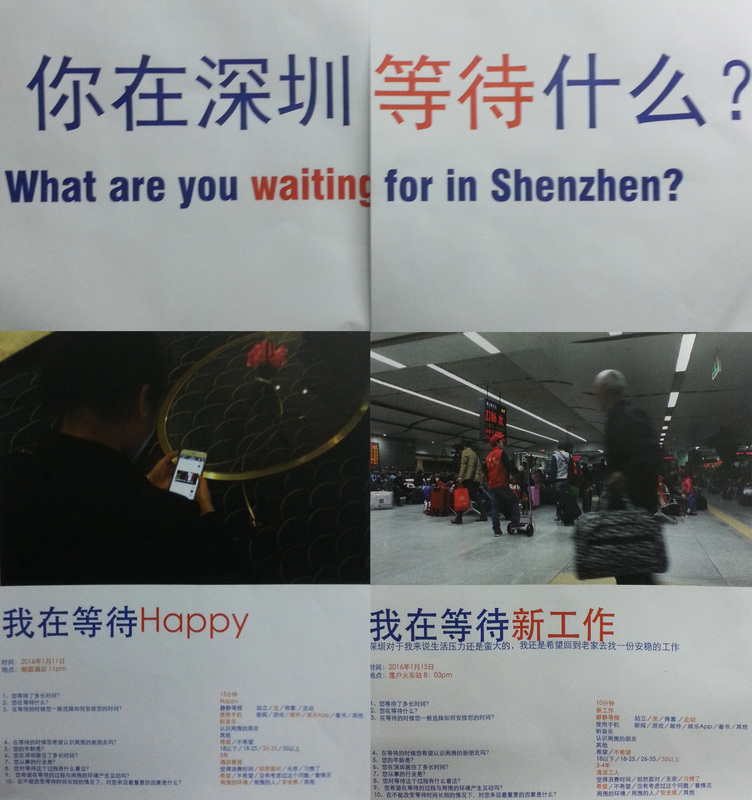

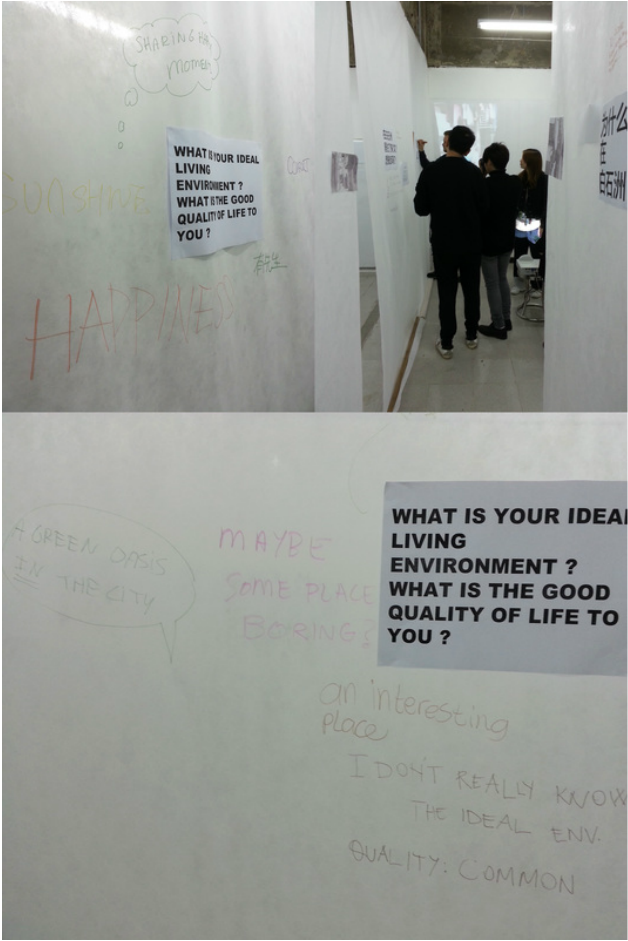

Learning from Shenzhen: The City as a Studio, was conceived and led by Thomas Kong. It formed part of a series of studios organized by the Aformal Academy during the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture. In this 5-day studio, participants were involved in a number of micro, on-site investigations centered on the interplay of everyday life, urbanization and globalization in China’s first Special Economic Zone. Waiting Everyone waits. Despite the fast pace and busy life of Shenzhen's residents, waiting is one common social phenomenon that binds everyone in the city while the cellphone is the indispensable electronic companion to alleviate the boredom of waiting. What do we actually do with our cellphones when we wait? What are we waiting for in the first place? These seemingly naive questions formed the basis of Lai Sihan and Gongyu's work. Uniform The love hate relationship between Shenzhen students and their school uniforms was the focus of Xia Weiyi's work. As the city continuously erases and rebuilds at an incredible pace, the ubiquitous school uniform that Shenzhen students wear daily becomes an identity anchor for many. However, it is not just a passive acceptance of the uniform attire by the students. As Weiyi's work showed, the relationship is one of creative improvisation, and negotiation with personal identity, memory and authority. Good life Shenzhen's economic development has brought transformational change to the lives of the residents. The urban village of Baishizhou exemplifies the mix of hope, ambition, opportunity and squalor that comes with the city's relentless push for urban and economic growth. Inspired by their work in Baishizhou, Deng Yinjie and Huang Jiangshen set up an installation that solicited from the visitors to the studio their ideas of a good life in Shenzhen and beyond. Form follows signage Like tattoos on a body, the advertisement signs follow the contours of the building's form in Shenzhen. It is almost impossible to distinguish between advertistment signs and the building's surface. Taking this premise, Ali Keshmeri's work re-imagined a new architectural form arising from the locations and shapes of the signage. Shenzhen Vending Machine Lin Simin and Zou Yizhi’s designed and made a vending machine, which they placed in different parts of the city. The machine had three buttons- money, love and water. They were associated with the economy, the body and human relationship. Unlike the vending machines in the city, their version did not offer what it promised. Instead the machine frustrated the user by consistently failing to vend what was desired. Drawing Memories

As the only participant who grew up in Shenzhen, Lui Min witnessed first hand the urban transformation of her city. She noticed places that had formed an important part of her life growing up in Shenzhen were no longer around. Through her mnemonic drawings, she recalled several memorable moments at different stages of her life. Make a model of a building

Use only things bought from the Dollar Store Title the model "A Mountain of Debt" Trade or give the model away on Craigslist Call a random number

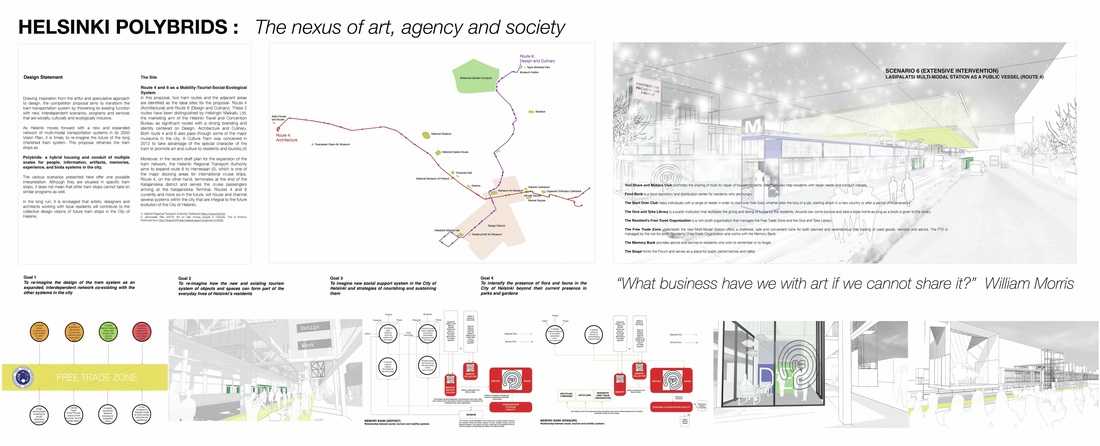

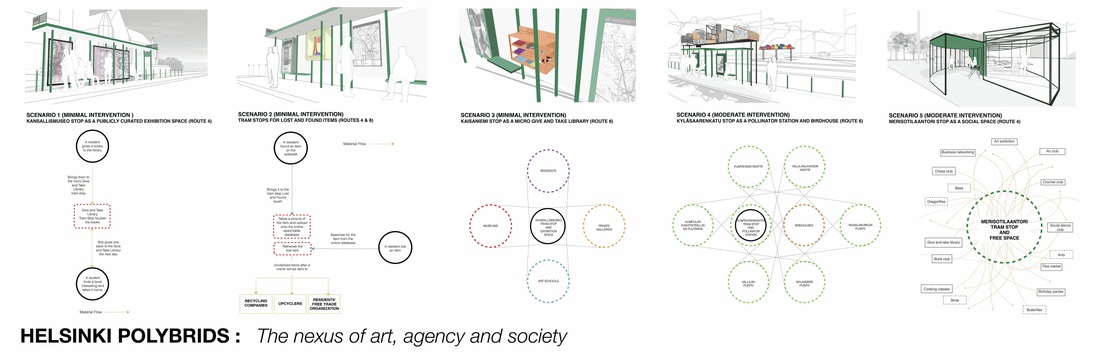

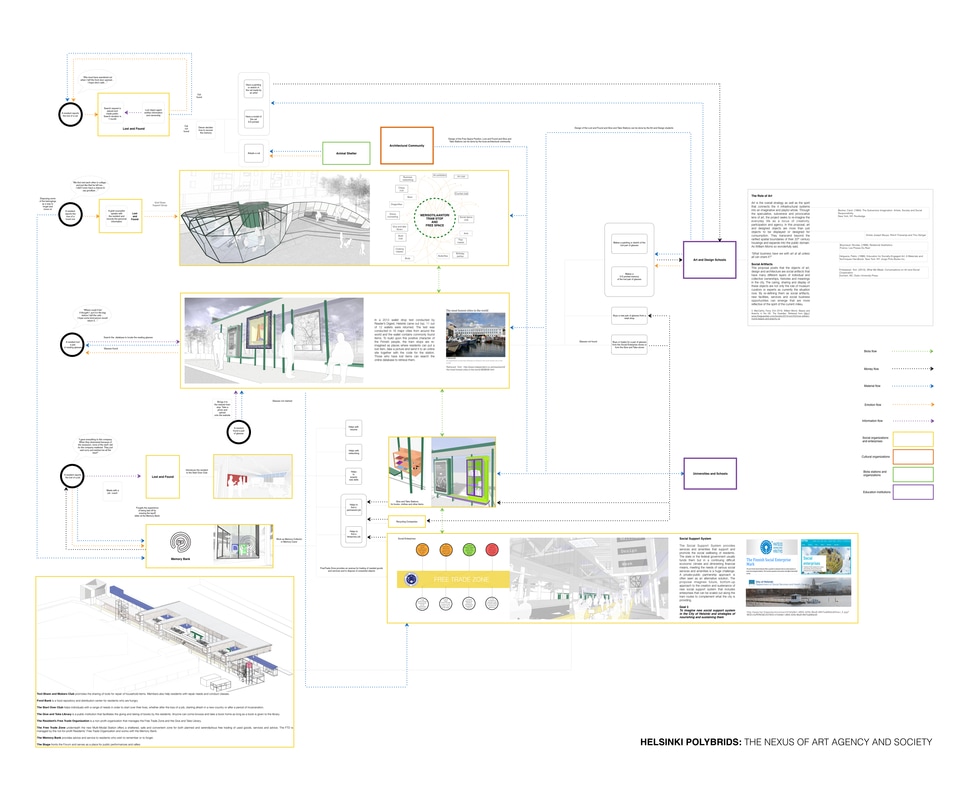

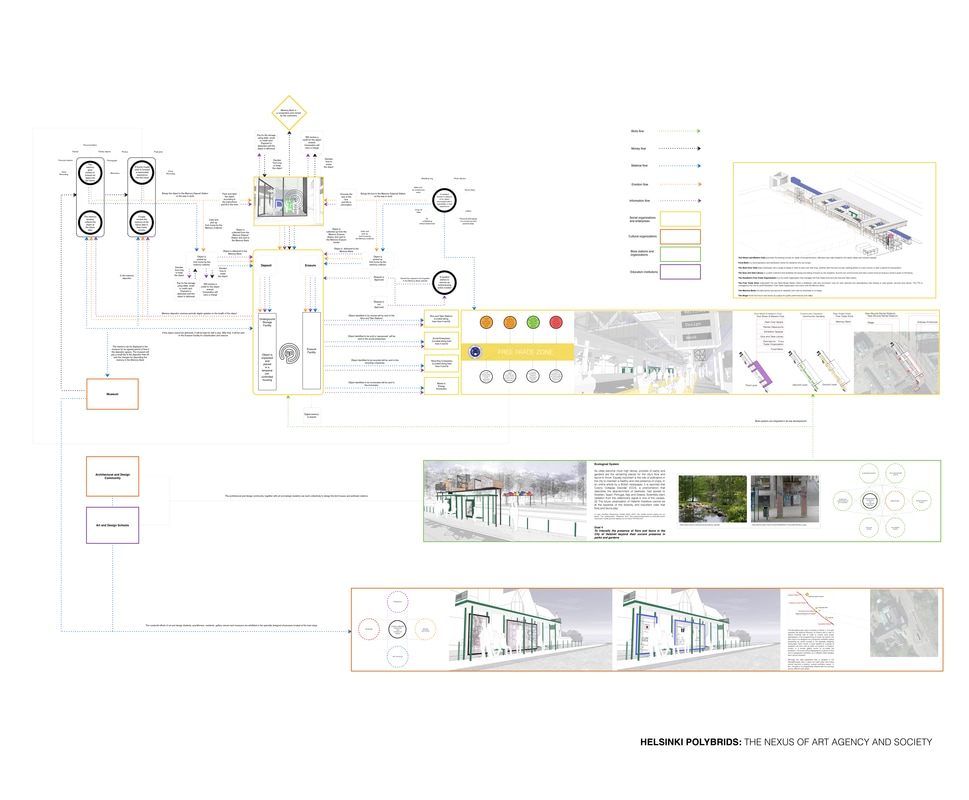

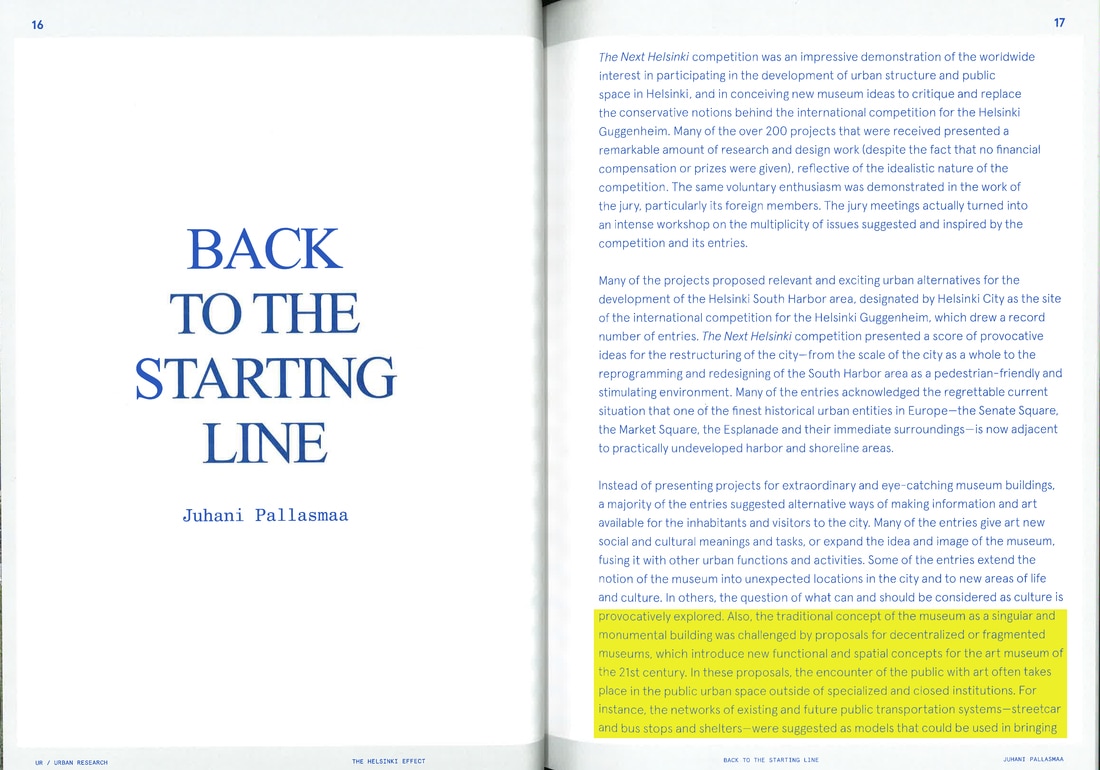

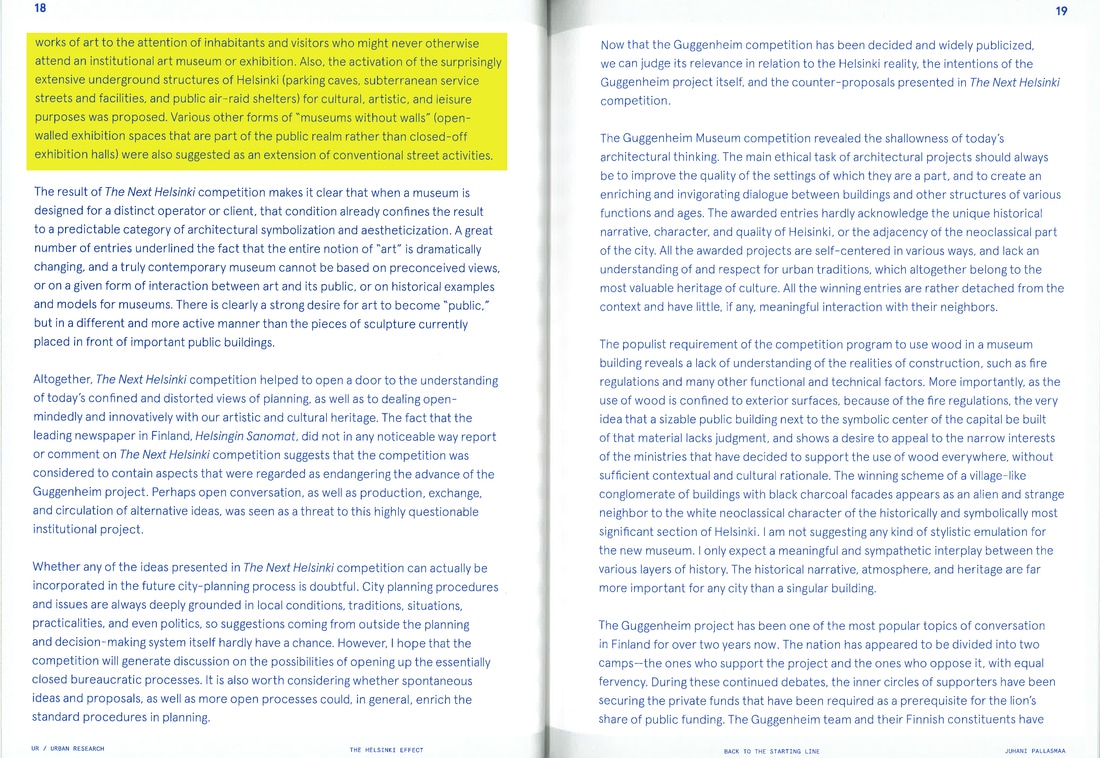

Ask for 'Thomas' Repeat the act with another number Stop when 'Thomas' answers "Helsinki Polybrids: Nexus of Art, Agency and Society" has been recognized by the jury panel of the Next Helsinki international architectural competition chaired by Michael Sorkin. Among the jury members are Juhani Pallasmaa, Walter Hood, Sharon Zukin and Mabel Wilson. There were over 200 entries from 40 countries. ”Almost like a dictionary of human thought and collective imagination.” (Free quote from jury member Juhani Pallasmaa) https://www.facebook.com/TheNextHelsinki 'Almost everything in the world today is mobile. Why should art be static?' Juhani Pallasmaa #NextHelsinki https://twitter.com/CheckpointHki https://homes.yahoo.com/news/adventures-architecture-next-helsinki-adds-212325775.html http://www.nexthelsinki.org/ My shortlisted proposal and the other 200 over entries form a collective and creative counterpoint to the corporate driven art market initiative of the Guggenheim Museum. Our proposals are part of the major debate over the long term value of the Guggenheim Helsinki project, which has faced massive push backs from Finnish citizens and prompted the setting up of an alternative international architectural competition. Since the Great Recession, city officials are realizing that big, iconic projects are becoming harder to push through in parliament because citizens are demanding for greater investment in social infrastructures instead. However, to avoid financing public art is also ill-advised as it is an important contributor to the culture and economic vitality of cities. A new model of art-making, curatorial practice, presentation, support, housing and archival will need to be designed. To avoid succumbing to the seduction of another one-off piece of iconic architecture costing billions of dollars to build, exploits cheap migrant labor and requires long-term, expensive maintenance, my entry re-frames the making, curating, exhibition and sustenance of artworks as a bottom-up, community driven activity that involves a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the city. It sees economic value of art not limited to how much one can afford to pay and sell at an astronomical price later but a more socially distributive model where the ecology of production, distribution and use (and re-use) is intertwined with the everyday life of the Finnish residents. Instead of scaling up even bigger as most contemporary museums seem to suffer from these days, my entry proposes to scale-out into the different neighborhoods by borrowing the city’s existing tram lines and stops. Through the process of creating the multiple art polybrids in the city, the tram lines and stops, which serve a vast section of the Helsinki residents and are in a state of decline, get to be refurbished and renewed at the same time. This twinning of art and public infrastructure makes good economic sense. The art polybrids are also way more accessible than a singular building, and are more effective in harnessing the collective imagination and creativity of the people. Museum goers are no loner passive consumers of a paid experience. They have the power and the opportunity to co-curate, to make art and in the long run, strengthened community bonding and identity, as well as fostering a more inclusive and socially resilient society. Helsinki Polybrids: The Nexus of Art, Society and Agency is therefore designed to offer a multi-scalar, horizontally distributed, economically and socially sustainable re-framing of art, its production and experience for a 21st Nordic city. The entry was exhibited in the recently concluded Tallinn Architecture Biennale in Estonia under the Research and Development Lab, which saw 1600 visitors over 12 days. The result of the Next Helsinki Competition has also been featured in many influential architecture and design websites, and the Finnish Broadcasting Company. In 2016, the book UR: NextHelsinki by Terreform containing the short-listed entries and essays will be published to document the process and the discourse surrounding the alternative competition, which no doubt will rouse further interest and attention. Academics too, have shared their perspectives on the contentious issue. Writing on the shortlisted entries for the Next Helsinki architectural competition, Peggy Deemer (2015) wrote, “The cultural value of this competition will probably not be in the form of creative capital—although the shortlisted proposals offer excellent thinking on what makes a city work such that art can be appreciated.” (para. 9) Referring to the Next Helsinki architectural competition again, Deemer (2015) was convinced that, “its very existence as performance, display, and conversation—its cultural capital—forces the Guggenheim to scurry and scratch for its rewards.” (para. 9) Besides being in a critical moment in the global discourse to unpack, critique and contextualize the value and purpose of such lavish projects, my shortlisted entry offered an alternative model to the Guggenheim museum franchise that weaved together the art, mobility, tourism, social support and ecological systems in the city. On a professional level, my proposal is a continuation of my research on and formation of a parallel architectural practice and education model inspired by the arts. According to the Legal Information Institute (2015), the definition of the ‘the Arts’ by the United States Congress includes architecture, besides the commonly accepted artistic practices such as sculpture, painting and photography. This inclusive definition opens up the possibilities for the creative renewal of not only the architectural profession but the teaching and learning of architecture as well. The breadth and scope of design services have also increased enormously in recent decades to encompass service design, design activism and strategic design, to name a few of the new fields. The strategic design thinking and human-centered problem identification skills used by architects in their daily practice can therefore be developed and marketed as new skills-sets and services to buffer against another economic crisis. Fluid/Soundings in London and AMO in the Netherlands are excellent examples of such an interdisciplinary practice. On the other hand, the nomination of architecture collective Assemble in the U.K. for the 2105 Turner Prize in Art is a strong endorsement of design activism and the art-design nexus of contemporary spatial practice. In my conversation with a design strategist working in the multidisciplinary American architecture firm Gensler, it was very clear to her that their major clients are not only interested in just a well designed and sustainable building but also a strategic vision that aligns architecture with social and business innovations, as well as environmental stewardship. Architect Michael Sorkin, the organizer of The Next Helsinki architectural competition puts it most provocatively when he declared in an interview with the U.S. based Metropolis magazine, “We invite competition entries from any and all, includes any of the 1,700 losers from the Guggenheim competition whose work looks beyond simply building a museum on the site.” (M, Sorkin, personal communication. Jan 22, 2015). Reference Deemer, Peggy. (2015).The Guggenheim Helsinki Competition: What is the Value Proposition? Avery Review: Critical Essays on Architecture. Issue No. 9. Retrieved from http://www.averyreview.com/issues/8/the-guggenheim-helsinki-competition Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from Cornell University Law School site https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/952 Revised drawings showing the ecology of existing infrastructure, education and cultural institutions, social agencies and parks as spaces for art making, sharing, presentation and community engagement. Architect, Professor and competition judge Juhani Pallasmaa's acknowledging the Helsinki Polybrids entry in his essay, Back To The Starting Line.

Project Mission

The Art and Design School Project is an interdisciplinary and creative project that offers a free, intimate and intellectual experience within a gallery setting for the discourse on art, design and contemporary culture. It is motivated by the tradition of experimental pedagogies and seeks alternative grounds for engaging the community of learners through non-conventional means of teaching and learning. Project Rational and Goals The Art and Design School Project is conceived first and foremost as a project. It exists as a liminal presence within a real space and is engaged with live participants but is fictive at the same time. This strategy supports the realization of the project’s goals while giving it the space to be experimental and critical. It challenges conventional structure and organization of a school, the methods of knowledge delivery and exchange, as well as the roles of learner and teacher. The project is strongly motivated by the possibility of opening up new concepts and strategies for the future teaching and learning of art and design. The Art and Design School Project therefore:

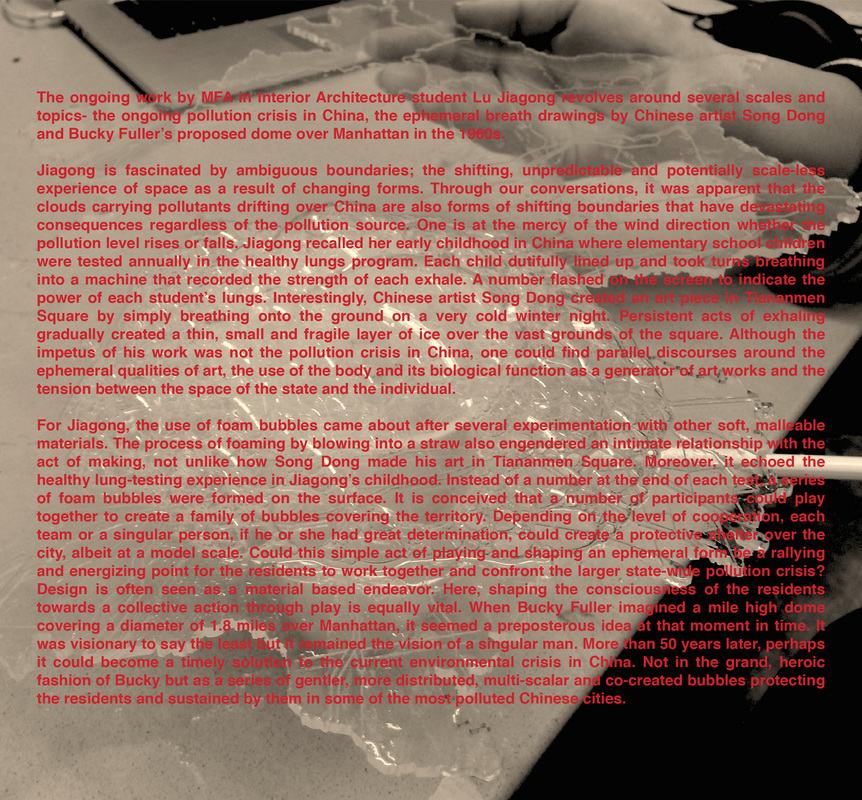

Project Organization The themes for the class will be crowd sourced and curated from the art and design community prior to the start of the project. A collective of artists, designers and scholars who have devoted considerable time to their work and who share a passion for this open, interdisciplinary form of knowledge exchange will be invited to facilitate the weekly thematic discussions. Practitioners and recent graduates in their respective creative fields are eligible to apply as student participants. They are selected from an open call for application and successful applicants are invited to join the Art and Design School for a 12-week session. At the end of the session, the students present their works, research or findings to an invited panel of experts in the art and design fields. Project Duration All the participants will meet once a week for 2 hours in the evening at a gallery. The project will take 12 weeks to complete. As a kid growing up in Singapore, my mother constantly reminded me to avoid walking below dripping laundry hung out to dry from the high-rise, government subsidized apartment blocks. Besides the possibility of getting wet, she believed it would bring bad luck to the person, especially if it came from wet undergarments. I did not dare to challenge her stern advice, for fear that she may be right- at least the bad luck part...

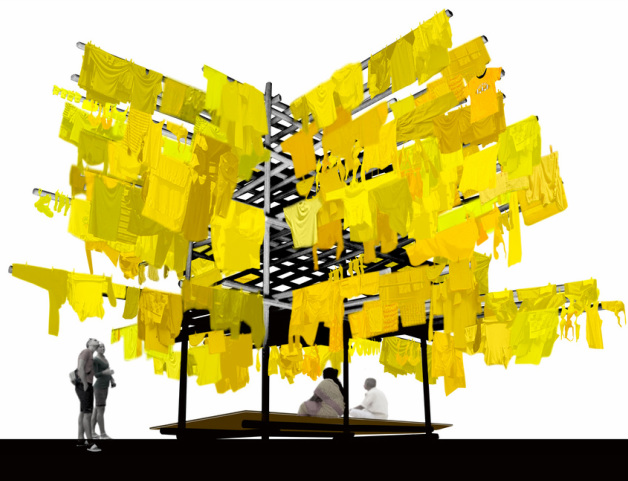

Laundry Art consists of two proposals for public installations that speak about the multi-layers of meaning, belief and the interplay between a simple, everyday practice in the city and the process of urbanization and modernization. One can see the correlation between how clothes are washed and dried, and the social transformation of the city-state through time from the history of laundry drying in Singapore. During the British colonial era, Indian laundrymen called Dhobis would collect, wash and dry the clothes in a vacant public space before sending them back to their customers. With the advent of the washing machine and the mass housing of urban dwellers in public high-rise apartments, clothes are washed indoors and dried using a simple technique of attaching wet laundry onto bamboo poles that are inserted into hollow steel pipes outside the apartment. The practice is mostly carried out nowadays by hired domestic workers from neighboring countries or replaced by laundry dryers. The domestic workers have to get used to this practice in a relatively short time as failure to do so may result in falling to one’s death. The heavy influx of new immigrants to the city-state the past few years also meant that newcomers need to be mindful of the implicit outdoor laundry drying etiquette if they were to avoid incurring the rage of local residents. Recently, architects designed the new high-rise apartments by cleverly shaping the building façade to hide this unique practice. It was deemed that wet laundry sticking out of government subsidized housing blocks is ugly, a nuisance, and potentially dangerous. Perhaps even a sign of backwardness? In a sense, what began as a practice, which took place outdoor and presented in full view of the public has been interiorized and gradually made invisible in Singapore as the city-state constructs with ambition, vigor and unsentimental pragmatism towards the future. |

Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed